No one strives for truth in cinema because reality is simply too complex for good storytelling

Be it Lagaan (a period drama) or Swades (a social drama), I have just poured my thoughts into those films, especially with regard to our world, society and our nation. I really believe that patriotism is something that we are inborn with. You don’t have to tell a child that he is an Indian and he should be proud to be one. What needs to be inculcated in us is nationalism because that is dormant in all of us. This needs to be given more lift and power. We need to make people realise how we need to work for the upliftment of our country. So for me these things are very important and if I can bring those themes in while telling an entertaining story then why not?"

– Ashutosh Gowariker to Anuradha SenGupta on in.news.yahoo.com, viewed on February 26, 2008

It’s not a new story, not an old one, but a story that seems to recur with ugly frequency. A young man and woman, neighbours who have fallen in love, elope from home. They run away for two years. When they return the woman’s family tries to get her to go back home. A peacemaker from the boy’s side is killed and one more inter-religious marriage finds itself spattered in blood.

If you read this alongside the Jodhaa Akbar controversy, the reasons for the outrage on the part of the Rajput community clear up a little. The film has a Hindu woman marrying a Muslim man. This does not seem to have been about religious pride though it does figure somewhere. This was about the operations of the patriarchy.

In all patriarchal societies, for which one might read in all societies, it is the control of the womb that is of central importance. The woman is thus reduced to her capacity to bear children. And once she has borne those children her importance is effaced again because it is the religious identity of the children that comes into focus. This brings into play another of India’s recurring demons: demography.

Who has how many children and what religious identity these children will have is a question that has traumatised us each time the census figures are released. Since these figures do not tell us patterns of land ownership, since they do not tell us about the religious or caste identities of the owners of the nation’s wealth, since they are prone to misinterpretation of the most unscientific kind, no census is released without someone ‘reading’ the figures to indicate that India is rapidly turning into a Muslim nation. Or that the Christians are taking over.

(Recent developments in Orissa show that the clumsy nature of the religious Right’s desire to demonise minorities continues. The church is now to be associated with the Naxalite. That there is no credible evidence for this is another matter. That the chief secretary of Orissa says that there have been no forced conversions there does not matter. Hatred is not an emotion that allows for rationality.)

But why Jodhaa Akbar? After all, Mughal-e-Azam had already played out the scenario of Emperor Akbar, the Muslim, and Jodha Bai, the Rajput mother of Prince Salim, some time earlier. There is a scene in K. Asif’s classic film in which Akbar is shown participating in Janmashtami, a Hindu festival: he is pulling the palna (cradle) on which the infant Lord Krishna is seated.

No one seems to have objected to the film at all. No one seems to have questioned whether Jodha Bai was a real figure or an imaginary one. One could put this down to the palmy days of the 1950s when there was still a widespread faith in the ability of the republic of India to provide for all its citizens, when inclusivity was an automatic response rather than the exception to be treasured but this seems to me to tread dangerously close to a nostalgic reinterpretation of the past. (The Other, we have always had with us. It is only our response to the Other that has grown more crude.) And this also does not explain why the film’s coloured version, released a few months before Jodhaa Akbar, should not have evoked the same level of rage.

The DVD version of Jodhaa Akbar contains a series of disclaimers. Before the film begins titles run to background music:

"Historians agree that the 16th century marriage of alliance between the Mughal Emperor Akbar and the daughter of King Bharmal of Amer (Jaipur) was a recorded chapter in history…

"But there is speculation till today that her name was not Jodhaa…

"Some historians say her name was Harkha Bai, others call her Hira Kunwar and yet others say Jiya Rani, Maanmati and Shahi Bai…

"But over centuries her name reached the common man as Jodhaa Bai. This is just one version of historical events. There could be other versions and viewpoints to it (sic)."

DVD 3 contains a bonus feature: "Historical References". The disclaimer is repeated here and 12 books are offered, including, surprisingly, the novel Gulbadan by "Ruman Goden" by which presumably the compiler of this list meant Rumer Godden.

But that’s history. We have never been terribly worried about historical truth. Sohrab Modi’s Jhansi Ki Rani established the image of a brave and valiant queen fighting for her land, her people and only incidentally, her right to choose an heir. Her actual role in history has been ignored.

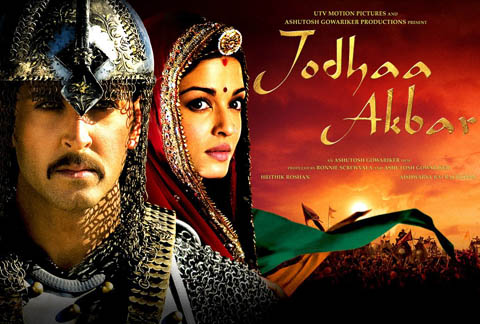

But then Modi was offering us a Hindu heroine. Gowariker is offering us a Muslim hero. His Akbar (played rather capably by Hrithik Roshan) is given to short justice but he is also the kind of person who grants a woman an audience, listens to her requests that she remain a Hindu and have a temple built inside her apartments, agrees and then falls in love with her.

None of this seems offensive to either side and it is a sad thing that such a question would still have sides determined by religion. Akbar himself was slightly more complex a character. His hunger for religious instruction meant that all ‘holy men’ were welcome at his court. And though they fought for the soul of Hindustan through the throne of the grand Mughal, Akbar seems to have managed a diplomatic way out of the mess of Muslim clerics and Hindu sages and Jesuit envoys: he invented his own short-lived religion. At Fatehpur Sikri you see the quarters for his wives and all the guides tell you about Jodha Bai and the Catholic wife from Goa, the Turkish wife and so on. The memory that remains with me is the small church, built exactly as if the architect had seen a child’s drawing of a church.

That may well be why no one strives for truth in cinema; reality is simply too complex for good storytelling.

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2008. Year 15, No.134, Cover Story 2