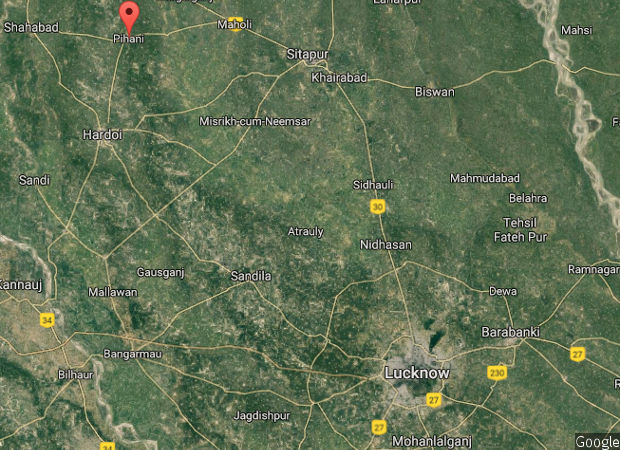

Pihani, Uttar Pradesh: For 16 years, Kailash Rai (not his real name), 49, has been commuting six hours every working day between his home in the state capital Lucknow and the government degree college where he teaches in Pihani, 135 km to the northwest.

A political-science lecturer, Rai cannot move with his family to Pihani, a cluster of over 100 villages (called a kasba) in Hardoi district, with less than 40,000 families as per Census 2011. When he started working there in 2000, it lacked the basic public facilities–regular power supply, good roads, public transport and good medical services.

Pihani remains an economic backwater. In the ongoing assembly elections, UP’s incumbent and contesting politicians are still promising the basic facilities they did 16 years ago: Electricity, buses and jobs, along with laptops and free data for poor youth.

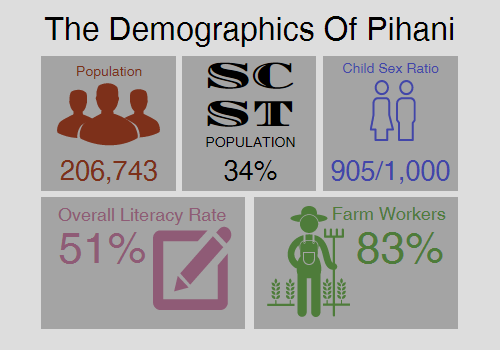

UP’s story parallels that of Pihani. The kasba’s population of 206,743 is serviced by four colleges–a government degree college, a state-run industrial training institute (ITI) and two private degree colleges–more than the Indian average of 27 colleges per 100,000 youth in the 18-23 age group, according to the All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2014-15. But it has been unable to produce talent to run local educational institutions, banks and medical centres.

UP has the highest number of colleges in any Indian state (6,026), according to AISHE 2014-15, but it has been unable to produce qualified workforce to drive development, as IndiaSpend reported on February 11, 2017.

UP is India’s most populous and youngest state–its median age is 23–and the flaws in its development model typified by Pihani explain why its towns and village clusters (blocks with a population of less than 250,000 in 2011) cannot cope with the aspirations of its people, especially with regard to education and employment.

Pihani’s dropout rate of 36% at elementary school level exceeds UP’s overall rate of 21%. Like other village clusters in the state, connections to bigger cities are limited because there are few railway links, hardly any feeder roads to highways or efficient public transport services. Less than half the houses in the villages have electricity.

UP has made higher education available everywhere, so why hasn’t the state become a hub for learning? Why doesn’t the state with the highest college enrollment in India–25% of men and women in the 18-23 age group–manage to create a pool of employable youth?

Some answers can be found in Pihani. The primary factor is the state’s disinterest in developing the basic infrastructure in its towns and villages that are now flush with schools and colleges.

Institutes have spread, so why hasn’t education?

Despite the large number of colleges in the district, Hardoi’s school education system is a mess. Only 64% of children in the district progress from primary to upper levels in school, according to data from the District Information for School Education surveys 2014-15. The all-India rate of transition from primary to upper primary level was 90%.

In a drive to push higher education in its backward pockets, many of UP’s colleges were set up in villages and kasbas. This growth was fuelled by both the government and private entrepreneurs. Hardoi district itself has 132 colleges, eight of them are government institutions–Pihani’s government degree college is one such–and 124 are private.

Over the years, the government degree college has acquired projectors, computers and generators but Pihani remains a backwater. This, according to Rai, is why the teachers at his college–and most employees in local banks, schools and hospitals–opt for long commutes from larger cities. They are what Rai describes as “reverse migrants”, working in villages and living in cities.

Pihani’s residents, it would appear, are not educated or skilled enough to fill in these jobs. The reason could lie in the quality of education.

“Government colleges are understaffed; usually, they work with one-third the required strength. This means that teachers are overworked,” said PC Joshi, a retired principal from a government degree college in UP.

However, he pointed out, private colleges have an even bigger problem. “Government colleges appoint qualified staff and the recruitment processes is fair and transparent. But privately-owned or funded colleges are often under-resourced in terms of physical infrastructure. And their recruitments are mostly on paper; in practice, there is hardly any teaching. There isn’t enough assessment of whether students are being taught regularly and adequately,” he told IndiaSpend.

Also, 17 less-populous states and union territories have better enrollment rates in higher education than UP: The union territory of Chandigarh reports India’s highest enrollment at 56%, followed by Puducherry at 46%. Manipur, among the north-eastern states has a 36% enrolment ratio in colleges. Among larger states, Tamil Nadu has India’s highest student enrollment in higher education at 45%.

There are other problems. The quality of education offered in colleges across UP varies widely because of lack of infrastructure. It is not rare in UP to see a college with two rooms, a clerk, an odd-jobs man and two teachers.

Second, colleges do not offer functional education geared to employment. The Pihani government college offers 10 subjects and degrees in undergraduate courses that include humanities and commerce.

“Most students come from poor families and also work in farms so they are not able to fulfil college attendance requirements,” said Rai. “Life is hard for these youngsters and the curriculum does not provide much functional education.”

Other than the proliferation of colleges, little has improved in Pihani, keeping its cluster of villages poor, badly connected and with scanty power supply.

A UP kasba: 100% rural, 83% farm workers

A community development block in Hardoi district, north-west of Lucknow, Pihani is an agglomeration of over 100 small villages. This rural administrative division is called a taluk or tehsil in other states. UP has 901 such blocks administered by a block development officer.

Source: Census 2011

A third of Pihani’s population consists of people belonging to scheduled castes and tribes. Its literacy rate is 51%, and less than half its women (41%) are literate. Women in Pihani form about 14% of the workforce, nine percentage points less than the national average of 27% as IndiaSpend reported in April 2016.

The kasba’s child sex ratio is 905 females per 1,000 male children under age six–better than its overall sex ratio of 873, according to Census 2011. UP’s child sex ratio of 902 is lower than Pihani’s. The overall sex ratio of UP at 912 females per 1,000 males shows poorer health indicators for women in Pihani.

Agriculture employs 83% of Pihani’s working population but 41% of these farm workers are labourers on the field–mirroring the 59% of UP’s population that works on farms, 51% of them farm labour, according to Census 2011. Others work as small traders, bank employees and government servants such as teachers, medical and administrative staff.

Electricity still elusive: 53% of UP homes without power

Only 47% of homes are electrified in UP’s villages. This puts the state fourth on the rural electrification list from across India–only Jharkhand (39%), Bihar (45%) and Nagaland (45%) are worse off, according to data from the power ministry.

A third of voters in UP cited power cuts as the biggest election issue, according to a survey conducted by FourthLion Technologies, a data analytics and public opinion polling firm, for IndiaSpend.

Less than half the rural households (46%) in Hardoi district have electricity in their homes. And those who do get power supply only for six to eight hours a day.

“Running a diesel generator is the only alternative. It costs Rs 50 to run a generator to run for an hour to power just the essential requirements on the college,” says Rai.

State roads: 9% of national highways in UP, but few links to these

Pihani’s nearest railway station is at the district headquarter in Hardoi, 28 km away. And it takes a two-hour bus ride to get there with many short halts along the way. Often, you can see passengers making the dash from their home as the bus waits.

A one-way railway ticket from Lucknow to Hardoi costs Rs 65. There are 29 trains between Hardoi and Lucknow and they run through the day. “But unpredictable delays cause a lot of inconvenience to daily commuters,” said Rai.

All the buses are private, and they charge Rs 25 from Pihani to Hardoi.

UP has the largest share (9%) of India’s national highways which run for 8,483 km. And it is ranked seventh when it comes to state highways, with 7,543 km of constructed length, according to data from the ministry of road transport and highways.

No national highway passes through Hardoi district. Only state highways connect it to the bigger road networks. NH-24, or the Delhi-Bareilly-Lucknow highway, is the closest to Pihani, 40 km to its north-east.

Road connectivity is an impediment for the farmers as it limits their access to markets. It also affects Rai and others who commute to smaller towns and villages.

The education-job gap: why Pihani needs more employment-oriented courses

Seema Gupta (not her real name), 19, is a student at the Pihani government degree college. It helps her that the college is easily accessible from her village, but her bachelor in arts degree is unlikely to get her a job. She would like to work to work in a cyber cafe–these are still popular in mofussil areas. But she needs additional computer training for this that is not available in Pihani.

Gupta would have preferred the college in Hardoi which offers technical courses but her parents did not want her to travel that far. “Safety is a big concern for women in Pihani,” said Gupta. “Parents allow boys to study in better colleges outside the village, but girls can’t travel that far.”

Despite these factors, girls form 60-65% of the students enrolled in the Pihani government degree college, according to Rai.

The government offers scholarship to students from economically weaker sections and backward castes, and for Gupta and many others like her, the Rs 6,000 per annum is a big help.

“But I hope my students can be offered better technical courses so that they have greater employability,” said Rai.

(Tewari is a PhD Scholar at the School of Development Studies, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, and an IndiaSpend contributor.)