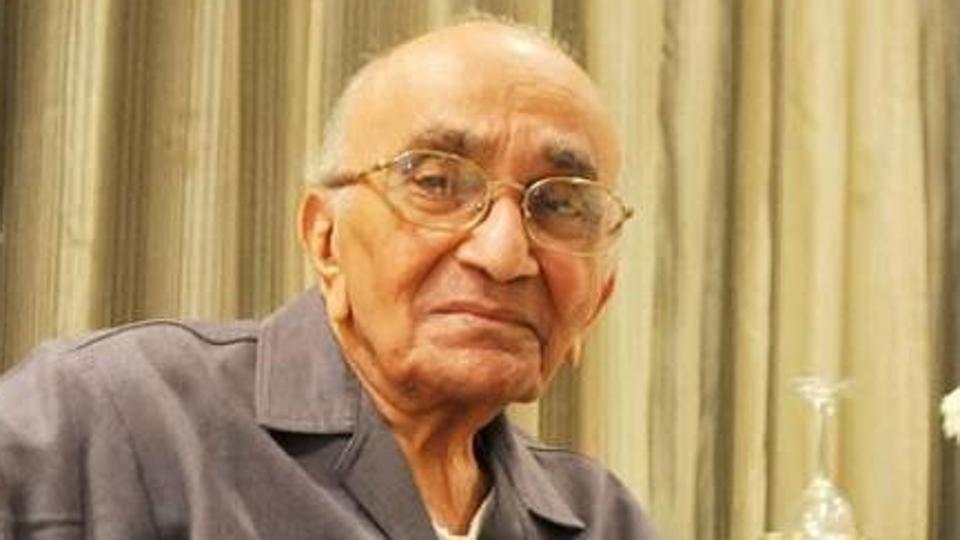

Bhagwati, J. has been celebrated as the pioneer of a comprehensive human rights jurisprudence in India. He has dramatically transformed constitutional understandings of the right to life and fundamental freedoms through judicial innovations and the introduction of a substantive rule of law. Here, we attempt to critically evaluate Bhagwati, J. from a human rights perspective for his contribution to constitutional law in India.

Darkest Hour for Human Rights in India

It is important to keep Bhagwati, J.’s decision in the infamous ADM Jabalpur case while tracing the trajectory of his subsequent judgments. Also known as the Habeas Corpus case presided over by the five senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, the judgment of April 28, 1976 has been condemned as a mortal blow to the cherished dreams enshrined in our Constitution. Bhagwati, J. concurred with the majority in closing the doors of justice for detenues during Emergency. Not only were Fundamental Rights, including the right to life and personal liberty, suspended; the Apex Court had effectively refused to fulfill its constitutional mandate of protecting the People against actions of the executive. The common man was terrorized with the hues of Emergency painting the nation in colors of silence, preventive detention, and human rights violations.

Active complicity of Bhagwati, J., though conceded to be an “act of weakness”, cannot be treated as a mere black spot on his career; “the instances of the Apex Court’s judgment violating the human rights of the citizens may be extremely rare, but it cannot be said that such a situation can never happen”. An apology rendered by Bhagwati, J. in 2011 does not diminish the bleakness of that judicial moment. However, Bhagwati, J.’s subsequent activist role in rewriting various constitutional articles ought to be appreciated, perhaps dichotomously, for his commitment to human rights activism.

Bhagwati and the Golden Triangle

Bhagwati, J.’s change of heart and judicial conscience is evident in his post-Emergency judgments. He immortalized Maneka Gandhi in a judgment that upheld her fundamental freedom to move and travel under Article 19(1)(d) by carving out the golden triangle of constitutional jurisprudence. By developing a substantive procedure established by law under article 21, Bhagwati, J. subjected any law, which may satisfy constitutional tests of article 21, to the tests of articles 14 and 19 as well:

“The law must therefore be now taken to be well-settled that Article 21 does not exclude Article 19 and that even if there is a law prescribing procedure for depriving a person of personal liberty and there is consequently no infringement of the fundamental right conferred by Art. 21, such law ill so far as it abridges or takes away any fundamental right under Article 19 would have to meet the challenge of that Article. Equally such law would be liable to be tested with reference to Art. 14 and the procedure prescribed by it would have to answer the requirement of that Article.”

Notwithstanding Bhagwati, J.’s political allegiance to the ruling government creeping into his judicial determinations, the Supreme Court judge has attempted to re-imagine his role in the judiciary through an unwaveringcommitment to socio-economic justice in upholding the constitutional validity of Article 31-C, which made any law enacted for the purpose of effectuating directive principles immune to judicial review under Articles 14 and 19, in the case of Minerva Mills v. Union of India.

Bhagwati: Father of Public Interest Litigation

While many regard the advent of Public Interest Litigation to bean act of judicial populism, Anuj Bhuwania argues that such populism of mirroring the political philosophy of the ruling government is one that preceded the Emergency. The legal aid movement spearheaded by Bhagwati, J. and Krishna Iyer, J. was an integral component of Mrs. Gandhi’s Twenty-Point Programme and the active role played by constitutionally mandated repositories of justice fell just about short of legitimating the Emergency regime. The rhetoric of the ‘People’ was yet another emulation as the judiciary attempted to refurbish its tainted image post-Emergency, by proclaiming itself to be the custodian of the Directive Principles of State Policy. In the case of State of Rajasthan v. Union of India, Bhagwati, J. eloquently upheld the proclamation of Emergency in the State of Rajasthan by surmising:

“There is a wall of estrangement which divides the Government from the people and there is resentment and antipathy in the hearts of the people against the Government…the Legislative Assembly of the State has ceased to reflect the will of the people…”

As he laid fertile ground for judicial innovations to follow, Bhagwati, J. justified relaxing rules of standing and “…devising new strategies for the purpose of providing access to justice to large masses of people who are denied their basic human rights and to whom freedom and liberty have no meaning.” The Judges’ Transfer case is apt to explain the assumed role of the judiciary by Bhagwati, J. as an “arm of the socio-economic revolution” to “perform an active role calculated to bring social justice within the reach of the common man”. Bhagwati, J.’s preoccupation with substantive justice enabled him to carve out avenues to disregard rigidity in procedural technicalities in order to effectively and meaningfully tackle issues of poverty, illiteracy and suffering. In assuming epistolary jurisdiction and encouraging people’s participation in adjudication, Bhagwati, J. fostered an era of unprecedented judicial activism that reprimanded prison authorities and the State machinery for keeping under-trial prisoners in jail for periods longer than the maximum term for which they would have been sentenced if convicted. He concisely articulated the purpose of public interest litigation as an attempt to “ensure observance of social and economic programmes, legislative as well as executive, framed for the benefit of the have-nots and the handicapped and to protect them against violation of their basic human rights, which is also the constitutional obligation of the executive.” Bhagwati, J. effectively imprinted juristic activism in the form of public interest litigation with the “insignia of an individual justice”.

He shifted focus to protecting the constitutional entitlements of bonded labor, child labor, children in observation homes, and workers in stone quarries, amongst others. Significantly, in the case of M.C. Mehta v. Union of India, Bhagwati, J. elucidated the function of the law to inject respect for human rights and the social conscience. This dynamic role of the law was used by the Supreme Court justice to create a new principle of absolute and non-delegable liability of corporations and factories that posed a potential threat to the health and safety of workers and people in surrounding areas for the social cost or harm caused by them. Bhagwati, J.’s focus on the outcome of social justice and human rights of the have-nots arguablyenabled him to justify deviation from procedural fairness. This gave way for subsequent justices of the Supreme Court to blatantly subvert procedure, such as the substitution of the petitioner with judge-appointed amicus curiae, disregard for evidentiary rules, heavy reliance on socio-legal commissions of enquiry, and refusal to lay down guidelines on the judiciary’s brief in regard to public interest litigation.

Bhagwati: The Death Penalty Abolitionist

An often-muffed aspect of human rights discourse is the death penalty debate, and Bhagwati, J. has proven to be a staunch abolitionist in this regard. His dissent in the case of Bachan Singh v. State of Punjab is memorable for his ethical and constitutional stand against capital punishment, as he dismissed the myth that the death penalty serves any social purpose of retribution, reformation or deterrence. In unhesitatingly holding death penalty to be violative of articles 14, 19 and 21 of the Constitution, Bhagwati, J. emerged as a true proponent of human rights law. This dissenting opinion deserves particular commendation for using international human rights instruments to buttress persuasive arguments that primarily focus on the individual and the prerogative of State instrumentalities to protect such an individual from State sanctioned infliction of human anguish and suffering. Significantly, Bhagwati, J. established a watershed moment for a conscientious judiciary that unpeeled layers of judicial abstraction and legal positivism by acknowledging that the death sentence has a certain class complexion:

“…it is largely the poor and the down-trodden who are the victims of this extreme penalty. We would hardly find a rich or affluent person going to the gallows. Capital punishment, as pointed out by Warden Duffy is “a privilege of the poor”…This circumstance adds to the arbitrary and capricious nature of the death penalty and renders it unconstitutional as being violative of articles 14 and 21.”

Bhagwati: The Realist

Bhagwati, J. died on June 15, 2017. With a mixed legacy of a grand people-oriented rhetoric and oscillating judicial outcomes ostensibly determined by the political ideology of the State, Bhagwati, J. exemplifies the workings of legal realism in the courtroom. It is about time we stop clinging onto the myth that exercise of judicial discretion is guided solely by legal principles. There is a growing need to study the social philosophy of judges to understand the politics, behavior, and reasoning of a Court that shapes the law of the land.

(The authors are students, Jindal Global Law School )