How Green Was My Valley II

The Sukinda valley in the Jajpur district of Odisha is a treasure house of mineral resources. On the one side of the valley, one finds the replica of the industrialized advancement of the Western world at Kalinganagar; while on the other side a contrasting situation stares you at Nagada. This contrasting sight perplexes the mind. Despite this, we still call Sukinda a land of wealth. And, it is also known as the land of `Black diamond ‘ for its vast treasure of chromite which has a place of pride in the world of minerals.

Chromite is extensively used in mineral industry, chemical industries, welding industries and refinery industries. Of the entire chromite production in the world, 94.5% is used in the mineral industry, 3.5% in refinery industry, and 2% in chemical industry. Iron, steel, cement, glass, ceramic industry, leather, paints, also make use of chromite. Of the entire chromites reserves in India, 98.6% is found in the Sukinda region of Odisha. It is true that Sukinda alone fulfils India’s entire domestic need of chromite. Not only that, Sukinda is one of the very few opencast chromite mines in the entire world. And today, the same Sukinda region that is the harbinger of prosperity is being ravaged by pollution.

Folk History of Sukinda

Folklore says that a young prince from Central India had once come to Puri along with his retinue of followers. As he was returning from his pilgrimage to Lord Jagannath, he had to pass through Sukinda along with its dense forests and mountain range. As night fell, he spent the night in Patana village with all his retinue. When the Prince woke up in the morning, his eyes fell on some bees hovering around some clothes drying in the open. The clothes belonged to the daughter of the sabara chieftain.

The prince felt that this girl is of the rarest quality – one in a million. He was keen to marry her. The sabara community chief agreed to give her hand in marriage to the Prince. The prince was overwhelmed by the abundance of natural scenic beauty of the forests and the mountain range. He made up his mind to settle there. He sent his retinue to his father’s kingdom and asked for more money and wealth. Gradually, the Sukinda kingdom was established.

Since the Prince was married to a girl of sabara community , till date the royal family of Sukinda is regarded as maternal cousins by the entire community. According to the accounts of the royal family, it is known that forty six generations have continued since the time Srikar Bhupati first settled here.

Over a period of time, the family left Patana village and went to Pataballi village near Tomka and Sukinda Garh. It is thus ascertained that people have inhabited this region since time immemorial. And the inhabitants are largely sabara. In course of time, other adivasi communities as well as Kudumi community have settled in the valley. Now, in the seven gram panchayats of Sukinda, the majority communities are Munda and then Sabara. In addition, there are adivasi communities like santhals, maatia, juanga, malhar, bhatudi and bhoomija.

The Damsala Nalla – the sorrow of the region

There are many natural streams flowing south from the foothills of the Daitari mountain range and north from the foothills of the Mahagiri mountain range. They empty into the Damsala Nalla at Kansha. The nalla flows down south-west for 35 kilometres before joining the Brahmani river. The Mahagiri mountain range is 300 metres above sea level and the Damsala Nalla is flowing at a height of 100 to 180 metres. The annual rainfall of this region is 2400 millimetres.

The chromite mines are located on both sides of the Damsala Nalla. People on both sides of the nalla have been dependent on its water for agriculture as well as domestic use. Around 20 natural streams from Daitari and 18 streams from Mahagiri flow into the Damsala Nalla. Most of the mines begin from the Kansha village that lies on the south of the Mahagiri mountain and continue up to the Kalarangi Atta village. The canal meets Kharkari canal here at Kalarangi Atta and flows south to the Brahmani river.

At Kalarangi Atta, a barrage has been built on the Damsala Nalla and the water is being channelled through the canal. The length of the canal is over 35 kilometres. It extends up to Bhuban village of Dhenkanal district. The following table lists the 75 villages that depend on the water of Damsala Nalla.

| VILLAGES EXPOSED TO THE POLLUTED WATER OF DAMSALA NALLA | |||||

| 1 | Tungeisuni | 26 | Bhimatangar | 51 | Kansargoda |

| 2 | Kansa | 27 | Kalarangiara | 52 | Barua |

| 3 | Balipura | 28 | Kothapala | 53 | Kaisiri |

| 4 | Penthasahi | 29 | Bhalutangar | 54 | Ramkrusnapur |

| 5 | Talanga | 30 | Bandhania | 55 | Balijhati |

| 6 | Kamarda | 31 | Daratota | 56 | Samal |

| 7 | Gurujanga | 32 | Koriapal | 57 | Dangardiha |

| 8 | Patana | 33 | Sitalbasa | 58 | Marthapursasan |

| 9 | Ostia | 34 | Mahidharpur | 59 | Dangabahali |

| 10 | Ostapal | 35 | Mochibahal | 60 | Malpura |

| 11 | Dhabahali | 36 | Bherubania | 61 | Nuagan |

| 12 | Kulipasi | 37 | Kohlinia | 62 | Dayana bila |

| 13 | Kaliapani | 38 | Kanheipal | 63 | Ragadipada |

| 14 | Chirigunia | 39 | Baragaji | 64 | Tipilei |

| 15 | Chingudipal | 40 | Badakathia | 65 | Angei Tiilei |

| 16 | Rangamatia | 41 | Baranali | 66 | Gabagoda |

| 17 | Baadbena | 42 | Oriso | 67 | Murgakasipur |

| 18 | Godisaahi | 43 | Belpahad | 68 | Srirampur |

| 19 | Maruabili | 44 | Baghua pala | 69 | Alipura |

| 20 | Benagaadia | 45 | Ransolo | 70 | Mathakargola |

| 21 | Saruabilo | 46 | Krusnapur | 71 | Jiral |

| 22 | Kharkhari | 47 | Sapua | 72 | Dankardia |

| 23 | Ghagiasaahi | 48 | Khokasa | 73 | Kundigoda |

| 24 | Kochila baanka | 49 | Jamua | 74 | Kauri |

| 25 | Kusum Gotho | 50 | Palaspithia Goda | 75 | Sur Pratapur |

The waste disposals from all mining and refining activities are dumped into the Damsala Nalla. When chromium mixes with water, it turns into the toxic form of chromium hexavalent. As a result, it pollutes the Damsala Nalla, and, in turn, the Brahmani river. People have become prone to many ailments and diseases too. The wastage from the mining is gathered and piled into an artificial mountain (overburden). When the monsoons come, the waste as well as the chromite particles from the dumps flow into the Damsala Nalla. As a result the riverbed rises.

Therefore, floods have become a reality even with moderate rainfall. As a result of chromium hexavalent making the water toxic, people in these 76 villages are affected along with soil fertility and crops being destroyed too. Chromium hexavalent has become the biggest concern of these 76 villages. The water discharged from the mines contains iron, nickel and copper particles which poses serious health hazards.

Since mining operations go down more than 100 metres, there is depletion of ground water. Most ponds and wells do not have water for half the year. Thirty streams – big and small – have dried up completely. The few remaining streams that bring water still remain dry for half the year now. The following table lists the perennial streams that have been polluted in the last many years.

| Perennial Streams in the Sukinda Region that Are Polluted | |||

| 1 | Kankada jhara | 17 | Kundapani jhara |

| 2 | Mankadchua jhara | 18 | Anjani jhara |

| 3 | Ashok jhara | 19 | Khandadadhua jhara |

| 4 | Kansachanda jhara | 20 | Purunapani jhara |

| 5 | Kendu jharana | 21 | Kaliapani jhara |

| 6 | Usha jhara | 22 | Patana jhara |

| 7 | Kankada jharana | 23 | Jhuna jhara |

| 8 | Bunimayuri jhara | 24 | Mahukhunta jhara |

| 9 | Kaina jhara | 25 | Dhalangi jhara |

| 10 | Sandhatangara jhara | 26 | Tikarpada jhara |

| 11 | Panasia jhara | 27 | Ambajharana |

| 12 | Nachiakholo jhara | 28 | Champa jhara |

| 13 | Kakudiajhar | 29 | Kamarada jhara |

| 14 | Mahagiri jhara | 30 | Malharsahi jhara |

| 15 | Chuanali | 31 | Bhimtangar jhara |

| 16 | Puria jhara | 32 | Dehuri sahi jhara |

Those working in the mines or settled around the mines are exposed to water contaminated with hexavalent chromium. This is the cause of many diseases: asthma; intestinal haemorrhage; TB; kidney ailments; cancer, lung disorder, throat, problems in eyes and nose, skin problems, paediatric/ Uterus problems/oral /etc as a result of this pollution. Many women have gynaecological disorders that have remained untreated.

The most prominent sign of morbidity is that of people showing signs of premature ageing. According to a report of the Odisha Voluntary Health Association, 84.75% of deaths in the mining areas and 86.42% of deaths in the nearby industrial villages have taken place due to chromite mine-related diseases. People living in a radius of 1 kilometre around the mines are most affected along with plant and animal life. As a result, 25.47% people of this area are seriously affected by PID. It can only be surmised that this toll must have deepened by now. The Annual Report of the Indian Institute of Water Management has categorically stated that 70% of water and 28% of soil have become unsuitable for agricultural purpose due to the high toxicity level. The fact that harvested grains and greenery are not entirely free of the toxic effects of chromium hexavalent therefore cannot be ruled out.

Years of Government Apathy

In 2007, the Blacksmith Report created a stir and the rampant pollution of the region finally got the much awaited attention. Many research institutes conducted investigations and published reports. Many reports testified the presence of toxic levels in the water. However, it is most unfortunate that most companies have shut their eyes to this problem in their mindless pursuit of profits.

The Odisha State Pollution Control Board after refuting the Blacksmith Report has remained completely indifferent; who can the people of the region turn to? Concerned citizens of this area have repeatedly approached all levels of the administration with their grievances. But they have not got any response. All local political leaders too are aware of the serious plight of the region and its people. The local people have filed a petition in the National Green Tribunal of the Eastern Region. While the NGT issued a notice to TISCO, all other mining companies need to be made accountable too.

From the Odisha Mining Corporation to the entire range of private companies – nobody is concerned about controlling pollution. There will soon come a time when there will be no labour left to work in these mines. At that time, Sukinda would have transformed into a desert.

List of References

- Aarambha; Dec 26, 2007 ; 1 January 2008

- Ratnakar Dhakate and V S Singh: Heavy Metal Contamination in Ground water due to mining activities in Sukinda valley, Odisha, A case Study, June 2008.

- Vijayan Gurumuthy Aiyer and Nicose E Mastora Kiss : Unsafe Chromium and its environmental health effects of Odisha Chromite Mines

- OSA Fact Sheet – Health Effect of Hexavalent Chromium

- EPG Odisha: A Report on the water quality with regards to presence of hexavalent chromium in Damsala Nalla of Sukinda Mining Area

- Annual Report , IWM, 2017-18

- Indian Bureau of Mines: Monograph on Chromite

- S Das and S Pattnaik: Heavy Metal Contamination – Science Direct – 2012

- Alia Naz, Abhirup Chowdhury, BK Mishra, and SK Gupta – Human Health Risk from Drinking water: A Case Study of Sukinda; 2016.

Lambodar Mohanto is a community worker and researcher based in the area.

Contact Email Id: sukinda-matters@riseup.net

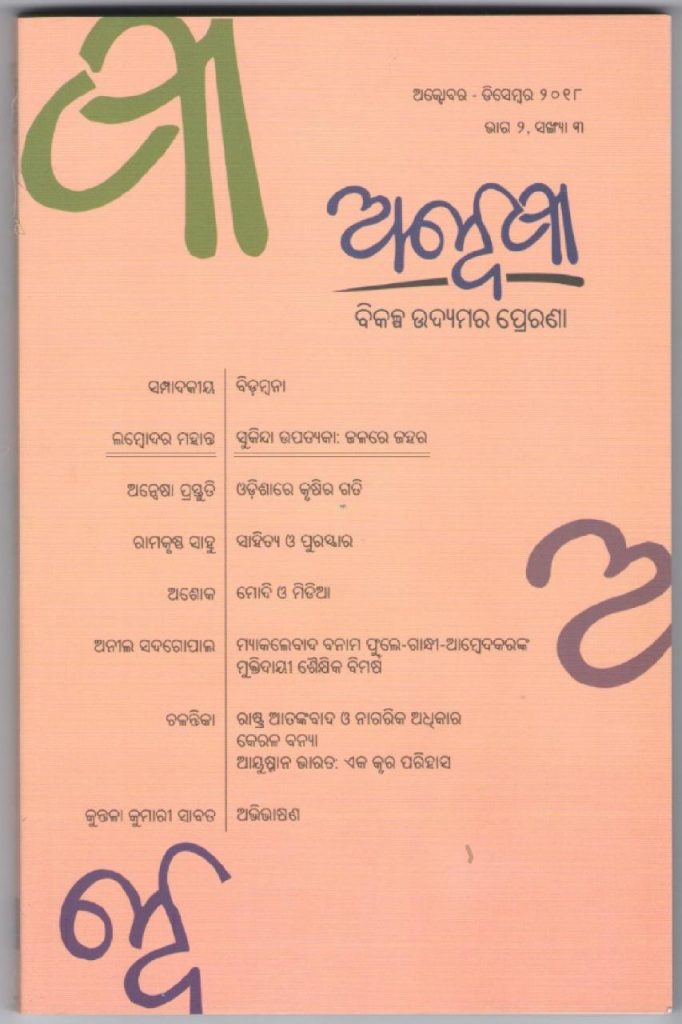

This article first appeared in the Odia journal Anwesha in Bhubaneswar. The author thanks the Anwesha team for its timely publication.

Anwesha is a quarterly journal in Odia that covers contemporary issues and reflections on politics, economy, literature, culture, caste and gender.

Courtesy: Counter Current