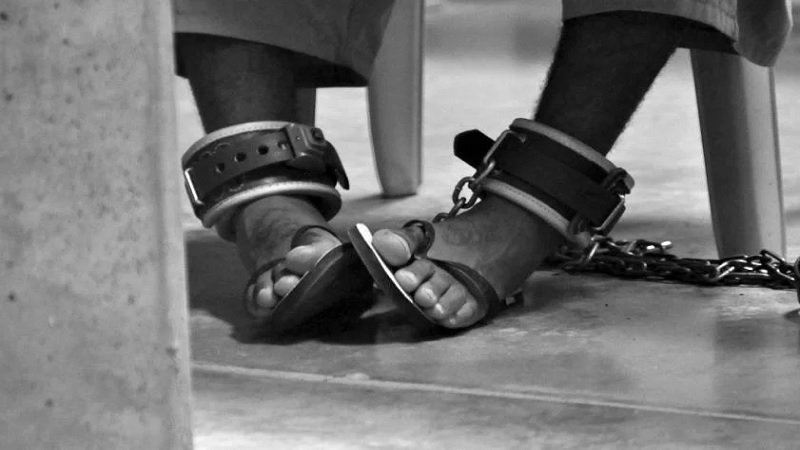

Image Courtesy: thewire.in

Image Courtesy: thewire.in

First Published on 07 Dec 2019

On December 4, Abdul Wahab of Indian Union Muslim League (IUML) about India being signatory to UN Convention against Torture and also sought data on number of custodial deaths in each state. He further asked if the government had a proposal to introduce a legal framework for custodial deaths.

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), with regards to the UN convention responded as follows:

“The UN Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment prescribes that each State shall take effective legislative, administrative, judicial or other measure to prevent acts of torture. The offences of causing hurt or grievous hurt to extort confession are punishable under sections 330 and 331 of the Indian Penal Code.”

About having a legal framework, the MHA said that the 273rd Report of the Law Commission and the draft of ‘The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2017’ has been considered by the government, along with comments from State government and that the ‘government is seized of the matter’.

The Prevention of Torture Bill

The objective of the proposed law is to ‘provide punishment for torture inflicted by public servants or any person inflicting torture with the consent or acquiescence of any public servant…’

The bill mentions that India is a signatory to United Nations Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

The bill defines torture as an act by a public servant or by a person with acquiescence of a public servant, causes grievous hurt or danger to life, limb or health (whether mental or physical).

Further the bill proposes punishment of minimum 3 years which may be extended to 10 years and fine, for torture inflicted for purpose of extorting confession, or for punishing or on the ground of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, caste or community or any other ground.

History of the law

The Prevention of Torture Bill, 2010 was introduced in the Lok Sabha to give effect to the provisions of the Convention. The Bill was passed by the Lok Sabha on May 6, 2010. Rajya Sabha referred the Bill to a Select Committee which had proposed amendments to the Bill to make it more compliant with the torture Convention. However, the Bill lapsed with dissolution of the 15th Lok Sabha.

Again in 2017 the bill was introduced as a private member bill in Rajya Sabha and then again in 2018, in the same form (private member bill) in Lok Sabha. The latter has lapsed due to dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha.

273rd Report of the Law Commission

This report of the Law Commission was in response to a direction by the Central government while taking note of a writ petition filed before the Supreme Court by a former law minister, Mr. Ashwani Kumar for implementation of the UN convention. The report traces the history of torture in India. It quotes from D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal[1] wherein the Supreme Court had observed, “Torture has not been defined in the Constitution or in other penal laws. ‘Torture’ of a human being by another human being is essentially an instrument to impose the will of the ‘strong’ over the ‘weak’ by suffering. The word torture today has become synonymous with the darker side of the human civilisation”.

The World Medical Association, in its Tokyo Declaration, 1975, defined “torture” as “the deliberate, systematic or wanton infliction of physical or mental suffering by one or more persons, acting alone or on the orders of any authority to force another person to yield information, to make a confession or for any other reason.”

Constitutional /statutory provisions for persons in custody

Article 20(3) – provides that a person accused of any offence shall not be compelled to become a witness against himself. The accused has a right to maintain silence and not to disclose his defence before the trial.

Article 21 – provides that nobody can be deprived of his life and liberty without following the procedure prescribed by law. The Supreme Court has consistently held that custodial torture violates right to life.

Article 22 (1) & (2) – provide for protection against arrest and detention in certain cases. It prohibits detention of any person in custody without being informed the grounds for his arrest nor he shall be denied the right to consult and to be defended by a legal practitioner of his choice.

India Evidence Act

section 24 – provides that any confession obtained by inducement, threat or promise from an accused or made in order to avoid any evil of temporal nature would not be relevant in criminal proceedings.

Section 25- provides that a confessional statement of an accused to police officer is not admissible in evidence and cannot be brought on record by prosecution to obtain conviction

Section 26 – provides that confession by an accused while in police custody could not be proved against him unless it is subjected to cross examination or judicial scrutiny

section 27 – Recoveries are not permitted to be procured through torture

CrPC

Sections 46(3) and 49 – a detenu who is not accused of an offence punishable with death or imprisonment for life cannot be subjected to more restraint than is necessary to prevent his escape.

Section 54 – extends safeguard against any infliction of custodial torture and violence by providing for examination of arrested person by medical officer.

Section 176 – provides for compulsory magisterial inquiry on the death of the accused in police custody

Section 358 – provides for compensation to persons groundlessly arrested.

Recommendations of the Commission:

The existing provisions under various statutes referred to hereinabove, convince the Commission to recommend that there is a necessity to amend section 357B to include a provision regarding payment of compensation in case of torture as well, in addition to payment of fine as provided under section 326A or section 376D of the Indian Penal Code, 1860. Similarly, the Commission is of the opinion that it shall be the responsibility of the State to explain the injuries sustained by a person while in custody, and therefore, recommends amendment to the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, by inserting section 114B on the lines of the Bill, viz., The Indian Evidence (Amendment) Bill, 2016, as introduced in Rajya Sabha on 10 March 2017.

The report also recommended payment of compensation to victims of torture at the hand of public servants or at the behest of public servant, as the case may be. Such compensation to be paid keeping in mind socio-economic background of the victim, nature, purpose, extent and manner of injury, including mental agony caused to the victim such as the amount suffices the victim to bear the expenses on medical treatment and rehabilitation.

Observations of the commission

Tolerance of police atrocities, amounts to acceptance of systematic subversion and erosion of the rule of law.

Torture is not permissible whether it occurs during investigation, interrogation or otherwise. It cannot be gainsaid that freedom of an individual must yield to the security of the State.

The Supreme Court in the case of Prakash Kadam v. Ramprasad Vishwanath Gupta[2], expressed its displeasure on fake encounters. The Court observed that in cases where a fake encounter is proved against policemen in a trial, they must be given death sentence, treating it as the rarest of rare cases. The policemen were warned that they will not be excused for committing murder in the name of ‘encounter’ on the pretext that they were carrying out the orders of their superior officers or politicians, however high.

In Dagdu & Ors. v. State of Maharashtra[3], the Supreme Court observed, “If the custodians of law themselves indulge in committing crimes then no member of the society is safe and secure.”

The doctrine of sovereign immunity – a concept of common law principle consistently followed in British jurisprudence in last several centuries that ‘King commits no wrong’. The doctrine evolved on the principle of sovereignty that a State cannot be sued in its own court.

What the bill misses out

The draft of the bill was also provided by the Law Commission in its report and there some provisions that have not been included in the bills as tabled in the Parliament. The report had included, “where torture in custody of a public servant is proved, the burden of proving that the torture was not intentionally caused or, abetted by or was not with the consent or acquiescence of such public servant, shall shift to the public servant.”![]()

The Commission’s draft had also provided for punishment of death or imprisonment for life for causing death of person in custody. The draft had also provided for compensation to the victim

The need for such a law

Out of 170 signatories to the United Nations Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, India remains one of the only eight countries yet to ratify the Convention. It it’s statement of objects and reasons, the bill states that ratifying the Convention reaffirms the Government of India’s commitment to the protection of basic universal human rights.

Between 2011 and 2013, 308 people died in custody and only 40% of these deaths led to cases being registered against them. Between 2015 and 2017, 289 people died in custody with Maharashtra recording 50 custodial deaths in this period, the highest amongst all States and UTs. The year 2017 alone saw 100 custodial deaths all over the country and of these, 58 people were not on remand i.e. they had been arrested and not yet produced before a court.

The Supreme Court, in 2017, observed that India’s efforts to extradite suspects from abroad are impeded due to the fact that India does not have an anti-torture law. The legislation, once enacted, will expedite India’s extradition attempts and the due process of law.

In conclusion

Clearly, after the first introduction by the UPA government of the bill, it has not been considered seriously by the following NDA government in the 16th Lok Sabha neither does the current BJP government seem to have any intention of introducing the bill on its own accord, thus the law has taken a back seat. The Union Home Minister has himself said once that western standards of human rights do not apply to India, thus weaning off the hope that in this term of Lok Sabha there will be any serious consideration of the Prevention of Torture law.

The complete bill can be read here.

The Law Commission report can be read here.

Related

100 Custodial Deaths Recorded In 2017, But No Convictions

When Your Deathbed is Behind Bars: NCRB Reports on Deaths in Judicial and Police Custody

Who are the Real Criminals? ‘Custodial Death’ leads to mob violence in Malda, 3 injured

Three sisters stripped and beaten at outpost in Assam, 2 cops suspended