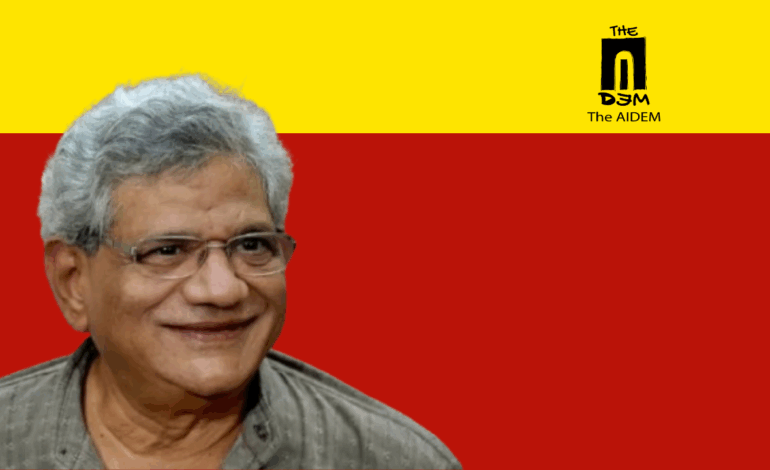

This is the full text of the first Sitaram Yechury memorial lecture delivered by eminent historian Professor Irfan Habib at Harkishan Singh Surjit Bhavan in New Delhi on September 15, 2025. Yechury, the former General Secretary of the CPI(M) had passed away last year. This in-depth ecture, explains how the ideas of democracy, socialism and communism have impacted our country, its people and its political leadership at diverse levels since pre-independence times. Prof Habib also points to how this multidimensional impact would sustain and progress in the days to come. A video link of the speech is embedded at the bottom of this text.

We are gathered on the first anniversary of Comrade Sitaram’s passing away. Knowing that he was General Secretary of the Communist Party of India (Marxist), and that Marxism is the basic ideology which the communist movement follows, I thought I should take the subject of the applicability and indeed the application of Marxist concepts and methods to India.

It is true that Indian criticism and opposition to British rule precedes the communist critique of British rule in India. Because already from the 1880s, Dadabhai Naoroji and his colleagues were sharply criticizing the way India was being exploited by British imperialism. And while today one is devoting oneself to the Marxist critique of British imperialism in India, it is also proper to pay respectful tributes to our own national figures, pre-eminently by Naoroji and R.C. Dutt, but particularly Dadabhai Naoroji, who described in detail how British colonialism was exploiting India. And while they used polite words, their critiques stand valid today as they were at that time.

So when we pay tributes to the earlier scholars, the earlier nationalists, and earlier scholars abroad like Karl Marx himself and Frederick Engels, we also pay tribute to Dadabhai Naoroji and R.C. Dutt in particular for bringing out how Britain was exploiting India.

I am today specially concerned with Karl Marx and the Marxist approach to colonialism in India and its consequences. Karl Marx’s criticism of colonialism was of course included in Capital, Volume One, and also in the subsequent two volumes, and also in his articles contributed to the newspapers in America, which have been published several times, both earlier from Moscow and now also from other places, with one addition coming from New York in 1991.

The communist approach to colonial India precedes the communist movement in India because this approach was first initiated by Karl Marx in his articles from the 1840s onwards, and also by Frederick Engels, in which they pointed out how British imperialism was exploiting India. But from the 1880s onwards, Indian economists, particularly Dadabhai Naoroji and R.C. Dutt, developed that critique, and although they often used courteous words, their content was singularly effective against British justifications of their rule in India. Therefore, as we celebrate what Karl Marx said against colonialism in India, we should also celebrate what Dadabhai Naoroji and R.C. Dutt in the late 19th century all said in criticism and denunciation of British rule and economic exploitation of India.

I have a feeling, I think, that the tribute owed to them is not effectively or adequately recognized in our universities and educational institutions. And I think therefore it is time that we should look at what they found to be wrong and evil in the British exploitation of India. Their publications, both by Dadabhai and Dutt, begin from the 1880s, and they pointed out how India was losing annually a large amount of its income and wealth to Britain—the so-called tribute, the drain of wealth from India. They were therefore the predecessors of communist critics, of Marxist critics, of British rule in India.

Our own communist movement began really in this century. And in the 1920s, various communist groups appeared, particularly influenced by the Soviet revolution of 1917, and created communist groups. Here it is not my intention, nor do I have the time, to go into the various stages in which the formation of the communist movement took place, particularly after 1917 and the Soviet revolution. But it is best to remember that by the 1930s, the Communist Party of India, a single communist party of India, had practically been formed. It had already resisted British repression, the so-called Meerut Conspiracy Case of the 1920s and others.

I’m sorry if I make a diversion because of a kind of piece of information which has not been seen in print, because it came from one of the judges. My father, Mohammad Habib, told me that in the 1930s he went to see one of the judges, Mr. Justice Sulaiman. Sulaiman complained that he was not able to sleep, and my father asked him why. He was Vice-Chancellor, or Chancellor (I forget which) of the Aligarh Muslim University and a judge of the High Court, later on promoted to what was then called the Federal Court at Delhi. He told him that it was because of “these blessed communists.” When the trial took place, he found that they were innocent and he told the British lawyer that what he was saying was absurd—that what he was claiming the communists did was not physically possible.

Justice Sulaiman said he was then called by the British Chief Justice, who said, “Do you know, Sulaiman, your name is being set for the Federal Court,” to which he was appointed later, “and if you mess up this communist case, you know what would happen.” And therefore, Sulaiman said that although he modified the punishments, he upheld the punishments where he intended to say that the law does not justify this kind of case. And therefore, he said, the communists went to prison for a few years more. This was what he told my father, and my father generally communicated this to me when he was reminiscing about previous cases. I found that this was indeed the case: that Justice Sulaiman had modified on appeal the punishments to the communists, but he did not dispense with the punishments; he only reduced them. And soon after, he was appointed a federal judge at Delhi and also won the vice-chancellorship of the Aligarh Muslim University.

So all these things that take place in life have to be considered, and justice certainly was in harm’s way when the cases of communists, particularly the so-called Meerut Conspiracy Case, came before judges. They might reduce the penalty, but they did not expose the fraud. And today, I think whenever we observe or think about the past of the communist movement, let us also think of our predecessors who suffered for us during the ’20s and ’30s and ’40s. That is why I am bringing your attention particularly to the so-called Meerut trials which took place in the 1920s of communist leaders.

As far as the communists were concerned, along with some leaders of the Congress like Jawaharlal Nehru and others, they were not tolerated by the Congress leadership. Again and again within the Congress, there were conflicts between socialists—among whom at that time communists were also counted (the differences with the so-called socialists came later). Sometimes it happened that whenever Jawaharlal Nehru and his supporters shifted, the left even obtained a majority among the Congress delegates, to the consternation of Mahatma Gandhi himself. Well, these are things which relate to some other aspect of history into which I am not going.

But we should remember that by the 1930s, the communists were a fairly important component of the Indian National Congress and often in alliance with the socialists. After the 1930s, however, there was a singular problem posed by the communal division. I think the time has come when even that particular period, roughly from the 1930s to 1947-48, should be freely discussed within the communist movement.

Our difficulty, of course, was that the Congress and Muslim League were pulling in different directions: the Congress for immediate freedom (which communists shared naturally) and the Muslim League for communal division, which fitted ill with communist ideology. How can communists be divided according to whether they were Hindus and Muslims? But there our leaders took a decision which had consequences, and frankly, I think that we are now at a reasonable distance from the 1930s and ’40s. It is time to take a position on that particular problem.

Those of you, and I think there would be many, who have read R. Palme Dutt’s India Today—there’s a whole chapter on India in India Today because this was written in 1945 or so—in which R. Palme Dutt, the major communist spokesman of the time both in England and India, laid out why India should not be divided on communal lines. It’s one of the most effective chapters of his book on India. Either our readers did not read R. Palme Dutt carefully enough, or there were other reasons why the Communist Party at that time decided to treat the Congress and the Muslim League in the same way.

Of course, with the Congress we had difficulties and differences on the question of the war, where after the German invasion of Russia, our position was that the war effort should be supported, whereas the Congress had still a large amount of hesitation on that point. This is not the place to go into a discussion of that. But it is important to realize that after 1941-42, our position with regard to the war was very different from that of the Indian National Congress, and that was one reason for the division.

The decisions that we took under that division, in which we equated the Congress with the Muslim League, is, I think, one which all fair historians should now freely discuss. They were not the same. The Muslim League was a communal organization; the Congress was not. The Muslim League cooperated with the British; the Congress opposed the British. On what ground could we then say that they were the same? That Muslim communists should go into the Muslim League and the others to the Congress? It is time now, I think, to look into our own shortcomings of the ’40s. I believe that this was a wrong decision, that this indeed divided the communist movement on communal grounds.

I’m afraid my memory is very bad; I forget names. But in the 1960s, a very important politician of Pakistan came to our house. He had been my father’s student, and my father had been a supporter of the Congress and the Communist Party—a peculiar position which he held with aplomb because both the Congress and communists were at some time in the ’40s, in particular, at each other’s throats, but by making donations to them both, he kept them satisfied.

Anyway, this chap came in about, I think, the 1960s (I forget his name). He was secretary of the Muslim League, and he began to blame the Communist Party for his discomfort. He said, “I was all right. I was like any communist leader you have here. I did not go to mosques for prayers and all that, and yet the Communist Party sent me to the Muslim League. And because as a communist I had learned to administer and work well, they elected me secretary of the Muslim League in UP. And when the partition came, I didn’t want to go to Pakistan, but the party said that you must organize the party in Pakistan. So I went there, and there’s no party in the name of West Pakistan,” he was talking of, “and I’m totally lost.” And for some reason, he blamed the present communists, including me (and my father was not a communist but a donor to the Communist Party). And he said that “because you did not fight against the Muslim League properly, I have been lost to the communist movement, and I have been lost actually to any serious cause because in Pakistan I have no interest left.”

In any case, the communal problem was a particularly difficult one for the Communist Party. But its decision that Muslim communists should go to the Muslim League and Hindu communists to the Congress, I think, was a very bad decision, and I think we should freely discuss these matters of the past because they have always shadowed the present. We should recognize that to put Congress and Muslim League at one level was not only a mistake but a grievous one. There was a communal party and a national party. The Congress at least had a socialist program at that time; they called it socialist. We might not call it socialist, but it was for public welfare. The Muslim League had no such program. How could you then ask Muslim communists to go to the Muslim League?

And therefore, as I was saying, a student of my father’s, whose name I’ve unfortunately forgotten because now I’ve become very old, came to our house in the 1960s complaining that the Communist Party was responsible for his discomfort. He said, “I did not want to go to the Muslim League, but P.C. Joshi called me and said, ‘Since you are a Muslim and we have very few Muslims, and we want to have a voice in the Muslim League, you should go there.’ And because the Communist Party had trained me well, I soon became secretary of the UP Muslim League, and then [went to] Pakistan and became a High Court, a Supreme Court judge in Pakistan.” And he blamed all this for his departure from Marxism. He blamed all this on Comrade P.C. Joshi and his policy of appeasement of the Muslim League.

I think it is time, of course, when we are discussing the history of the Communist Party, to freely consider whether this decision of the ’30s and ’40s of equating Congress with the Muslim League, and in effect treating Congress as a Hindu organization—because once you say that Muslim communists go to the Muslim League, then you are treating Congress as a Hindu organization—this was an enormous error. I think there should be free consideration of how these things occurred in the history of our party.

I think, however, that there are also difficulties for the communist movement which we should recognize, particularly because when Germany attacked Russia, what should have been our attitude? The only socialist country in the world attacked by the leading fascist party of the world, the leading power of the world. Should we then continue to say that the war is an imperialist war, or should we say that the character of the war has changed from a war between two imperialist powers, Germany and England? It has become a war between the fascist powers—Germany and Japan—and the leading workers’ republic, the Soviet Union, and our neighbor, people’s China.

There may be many who might think that the decision our party took was a mistake. But we decided that the war had changed from an inter-imperialist war; it had become a people’s war once Russia was attacked and Japan intensified its invasion of China. There are many who think that this was a wrong decision, that it therefore put us outside the Indian national movement because, remember, this was the time of the Quit India resolution of 1942—a resolution which even today looks very awkward when you think that Japan was on the Indian frontier. Was it right at that time to say that the British should quit India? That there should be immediate movement and agitation for it?

If you look at Jawaharlal Nehru’s own papers, far from trying to oppose the British government at that time, he was thinking of how the Japanese invasion would be tackled by Indians, how they would fight Japanese soldiers. Japan was the enemy in his mind. But for some reason, when the actual Congress passed the resolution, Nehru also concurred. And I think it is proper for our part today to question the wisdom of the “Quit India” resolution of the Congress of 1942, which actually initiated the so-called Quit India movement at a time when the Japanese were on our borders.

And you know what was the Indian people’s response? The police terror was there. There were demonstrations, but nothing like the demonstrations when earlier Congress movements had taken place—nothing like those. So although the socialists, in particular, then began to use bombs and so on—even in the Aligarh railway station, two people were killed by a socialist bomb, night policemen, nothing but ordinary people on the platform—and these things occurred because of the Quit India resolution.

I think it is right to say that the Quit India resolution was mistimed, that it should not have been raised at that time, that the enemy—Japanese and German fascism—should have been identified as the main enemy, with the British to be tackled later. I think this is what we should say today. And this is what the Communist Party then said, and I think we should stand by what the Communist Party’s position remained: that the initial task, once Hitler had invaded the Soviet Union, was to defeat the fascist powers, and then later on to tackle British imperialism. I think one further matter which needs our attention is that the Indian freedom movement should not be regarded as purely Indian; that we had friends in Britain. The British Labor Party had said even during the war that if it came to power after the war, it would free India. There had been, as you know, British communists who went to prison in India in the 1920s and early 1930s.

My wife and I were present at the funeral of one such British MP whose daughter, to our surprise, didn’t know that her father had been in an Indian jail for supporting the Congress movement. When we told her this, she was greatly surprised because, you know, it is one of the customs of the British that they don’t boast. So the father had never boasted about his imprisonment in India to his own daughter. When we told her about it, she was very gratified, but by that time, her father had been buried. Unfortunately, I’ve forgotten the name of the Labour MP. We still remember there was such a time. At his funeral—because he had gone to prison in the Meerut Conspiracy Case—the British High Commission, because of Mrs. Pandit, I think, sent a very large wreath to his funeral, and the wreath said, “Gratitude of India.”

Now clearly, the Indian national movement had its friends abroad, and today also we should honour them. As I’ve said, three British MPs went to prison in India for their support of the Indian National Movement. Today we are observing the memory of our past, deceased communist comrade. I think that while it is of course proper that all of us have assembled to celebrate and observe his memory, it is also important that we should also further support the cause for which he had stood: the cause of socialism and people’s democracy in India.

Before closing, I would say that both socialism and democracy are priceless values. One can’t be of value without the other. To think that socialism can be imposed by a dictatorship is, I think, a fallacy. And therefore, in India today, we should not only propagate socialism, but we should also propagate full democracy—that India should have a socialism which its people want, for which we have convinced its people. And today, as we observe the demise of a very precious comrade of ours, a major leader of our party, let us also consider within ourselves (I would not say take a pledge) but consider within ourselves how we can promote the further improvement of the cause of reason and socialism in this country, and how we can bring about a socialism which is, as far as possible, accepted by the vast majority of our fellow citizens.

Well, I think I have said what I wish to lay before you. Nothing is novel there; nothing innovative. But I think a reminder of these particular points should also have a place here. And therefore, while ending, I request you to consider, if you have not already considered, the points that I have raised.

Thank you.

Read the Malayalam translation of the speech here

Video link of the speech:

Courtesy: The AIDEM