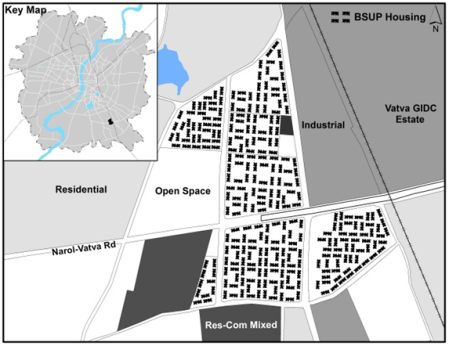

Urban beautification and infrastructure projects in Ahmedabad such as the Sabarmati riverfront project, the Kankaria lakefront project and road-widening projects, including for the Bus Rapid Transit System (BRTS), have displaced thousands of poor households since the mid-2000s. Many have been resettled in public housing built by the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC) under the Basic Services to the Urban Poor (BSUP) programme of the Central Government’s Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM). Almost half of this BSUP housing is built at seven adjacent sites in Vatwa. (Map 1). AMC allotted flats at three of these sites between 2010-2014.

The constrained mobility and stressed livelihoods created by displacement and resettlement to sites like Vatwa is a form of structural violence inherent in the development paradigm adopted in Ahmedabad over the past decade. Four dimensions of urban planning produce this structural violence. Distant relocation along with lack of appropriate and affordable transport options negatively impact the mobility, work and livelihoods of a vast majority. Both men and women are impacted negatively but in gender-specific ways. Lack of adequate social amenities nearby, coupled with lack of appropriate and affordable transport options, have also negatively impacted livelihoods. Increased expenditures for basic services and housing maintenance create further challenges for livelihoods. Finally, the unsafe environment at the resettlement sites, which is borne out of planning and governance dynamics, constrains women’s mobility, also impacting livelihoods.

“Poverty, Inequality and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning,” a three-year research project (2013-16) undertaken by Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University in Ahmedabad and Guwahati, and Institute for Human Development in Delhi and Patna, is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Canada and Department of International Development (DFID), UK, under the global programme Safe and Inclusive Cities (SAIC). The research analyzes the pathways through which exclusionary urban planning and governance leads to different types of violence on the poor and by the poor in Indian cities.

The CUE research takes an expansive approach to violence, examining structural or indirect violence (material deprivation, inequality, exclusion), direct violence (direct infliction of physical or psychological harm), overt conflict and its links to violence and different types of crime. We note that not all types of violence are considered as crime (for example, violence by the state), and not all types of crime are considered as violence (for example, theft).

In Ahmedabad, the largest city of Gujarat state, the research focuses on two poor localities: Bombay Hotel, an informal commercial subdivision located on the city’s southern periphery and inhabited by Muslims, and the public housing sites at Vatwa on the city’s south-eastern periphery used for resettling slum dwellers displaced by urban projects.

- DISTANT RELOCATION, TRANSPORT AND IMPACTS ON MOBILITY, WORK AND LIVELIHOOD

The households resettled at the Vatwa sites are 7-15 kms from their former neighbourhoods where they had lived for long and hence had found work places that were easily accessible. Many used to walk or cycle to work. Distant relocation has forced them to spend high amounts on motorized transport to reach work (See Box 1), entailing a reduction in their effective income. Many women have stopped working consequently, coupled with the difficulties that longer travel time creates for juggling paid work and household work. Many youngsters who used to walk to nearby central city areas and find casual work have stopped working since the irregular nature of casual work (i.e. no guarantee that one will find work on any given day) does not justify the transport expense. For casual workers, searching for work now depends on having money for transport. As a result, searching for work has itself become more irregular. Dropping out of the workforce and higher underemployment has severely impacted livelihoods.

Box 1: Public Transport (PT) and Intermediary Public Transport (IPT) Connections from Vatwa

Public transport at Vatwa consists of three Ahmedabad Municipal Transport Service (AMTS) buses. Given the distance and the fare increase in 2012, buses do not connect to all the work destinations of residents and have inadequate frequency (KBT Nagar local leaders have appealed to the government the AMTS fares to central areas of the city are high (e.g. Rs.14 one-way to Lal Darwaza – See map). These for one more AMTS bus route, but this has not yet been provided).

“Transport fares kill us.”

“We have been broken by transport fares.”

For those who have continued with their previous work, travel costs have reduced their effective income. For example, women domestic workers who walked to work from their homes in the Paldi, Lal Darwaza, Khanpur and Shahpur areas now spend one-third to one-fourth of their income on transport (Rs.30-40 per day; therefore, Rs.900-1200 out of a monthly income of Rs.3000-4000). Vendors used to keep their vending cart at home and walked with it to the wholesale market and/or their vending place. Now, they have to spend about Rs.300 per month to rent a spot for their vending cart at walking distance of the market or their vending place as well as on transport to reach it.

Many residents have shifted to other work due to the distance and transport issues. Many women have taken up home-based work. However, earnings are low. For example, women making plastic flower garlands or rakhis make less than Rs. 100 per day since the piece-rates are low (Rs.8 for making 12 dozen pieces). Earnings are more for stitching clothes (Rs.30 for dozen pieces). However, their earnings before resettlement were higher (Rs.100 for stitching dozen pieces) as they directly procured work from the trader. Post-resettlement, reaching the trader entails high travel costs (transporting raw materials / finished goods requires spending Rs.100-120 one-way for a metered rickshaw), making them dependent on middlemen who give work at reduced rates.

Some of the residents have shifted to self-employment by opening shops and stalls at/near the resettlement sites. Not all, however, have been able to maintain or improve their previous income levels as many sell the same few items and the clientele (mostly confined to the sites’ other residents) thus gets distributed among them.

Note that the nature of work available nearby (industrial work at the Vatwa GIDC industrial estate) is of a vastly different kind than what most residents have done (vending, domestic work, casual labour in construction or small-scale trade activities). Since it pays less for longer hours and harder labour, many do not see it as a legitimate option. Some Muslims also reported discrimination in the GIDC estate. Domestic work is available nearby, but this pays less than in the city’s centrally located areas.

- LIVELIHOOD IMPACTS OF THE DEPENDENCE ON TRANSPORT TO ACCESS SOCIAL AMENITIES

Residents were close to, or better-connected to, social amenities at their previous localities due to the latter’s more central locations. At Vatwa, only a primary municipal school, whose education quality is poor, is at walking distance. Reaching other amenities like the children’s former schools or private schools, public healthcare, colleges, and recreational open spaces entail new or higher transport costs. Residents also spend more on transport to access the public distribution system as the state has failed to facilitate the transfer of their ration cards from their previous ration shop to a nearby one. All these transport costs impact livelihoods. In many cases, residents have pulled children out of school, compromise on getting healthcare, etc, which would reduce their life chances.

Distant location de-links people from their access to social amenities given that peripheral locations in Indian cities inevitably lack these. The city’s expansion pattern is that people first move to the periphery, water and sanitation follow, and the last to come is transport. The costs of transition to the peripheral locations are therefore entirely borne by the households. For low-income households, this transition leads to reduction in effective family income through many routes.

- LIVELIHOOD IMPACTS OF HIGHER HOUSING-RELATED EXPENDITURES

There are increased expenditures on basic services and infrastructure maintenance. Many residents have been getting high electricity bills that entail paying more than double of what they used to pay in their previous locality. The maintenance of building corridor lights and water and drainage infrastructures entails new costs for residents. Residents have to pay the bore-well water operator Rs.20-30 per month. They are also expected to pay for repairing damaged water and drainage pipes and valves in their buildings. After AMC stopped repairing the motors in the underground water tanks in mid-2014, residents have had to pay for this also. The frequency with which motor repairs are required depends on various factors and can be monthly or once every several months (See Policy Brief 2 for a detailed discussion on basic services and infrastructure).

- IMPACTS OF UNSAFE ENVIRONMENTS ON WOMEN’S MOBILITY AND LIVELIHOODS

Theft and robbery, illicit activities, sexual harassment and sometimes even sexual assault, and kidnapping of children have been widespread at the Vatwa resettlement sites. Fear lurks even among those who have not directly experienced these crimes. As a result, many women have stopped work, which has also negatively impacted livelihoods. The planning and governance dynamics that have created this unsafe environment are discussed in Policy Briefs 3, 4 and 5.

As a result, many turn to shuttle / shared auto-rickshaws, a form of Intermediary Public Transport (IPT). These auto-rickshaws ply along fixed routes with fixed fares (instead of metered fares) and illegally take up to eight passengers (instead of the permissible four passengers). Women find the experience uncomfortable as they are forced to sit in close proximity to men. Shuttle fares are also quite high (e.g. Rs.15 one-way to Lal Darwaza).

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

- Displacement should be minimized and development decisions made after thorough consideration of the displacement it would cause and the risks posed by this for vulnerable groups.

- If displacement is unavoidable, resettlement should be in nearby locations so that residents’ mobilities and livelihoods are not negatively impacted. Distant relocation has negative repercussions for mobility and livelihoods as it entails higher transport costs as well as de-links people from the socio-economic networks they have established in and around their neighbourhood.

- Public housing for low-income households should be developed along with provision of good-quality, functioning social amenities so that they are accessible and minimize the transport expenditures of the resettled households.

- Enhancing livelihoods is essential for households to have the economic capacity to incur the higher expenses around basic services and maintenance in public housing. If livelihoods are not enhanced, these higher expenditures can create severe livelihood stresses (then residents cope by leaving infrastructures unmaintained, which affects their access to basic services and can also lead to conflicts).

- Government authorities should plan basic services provision and maintenance over the long-term after a realistic assessment of done before housing interventions begin. This would help to reduce the possibility of housing-related households’ economic capacities. This planning should be expenditures becoming a driver of violence and conflict.

Research Methods

- Locality mapping and community profiling

- Ethnography + ad-hoc conversations

- 11 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs)

- 7 unstructured group discussions (GDs)

- 35 individual interviews (leaders, water operators)

- Total 51 men and 53 women participated in the FGDs, GDs and interviews.

- Interviews with political leaders & municipal officials

- Master’s thesis: 10 FGDs (46 women) on transport and women’s safety.

*With this counterview.org begins a series of Policy Briefs, prepared by the research team of the Centre for Urban Equity (CUE), CEPT University, Ahmedabad, on “Safe and Inclusive Cities – Poverty, Inequity and Violence in Indian Cities: Towards Inclusive Policies and Planning”.

Courtesy: CUE, CEPT University, Ahmedabad