The misguided youth of today, trying to build their quick political career by subscribing to divisive ideologies, should be persuaded to look upon the rational and independent thinking icons such as Kripalani.

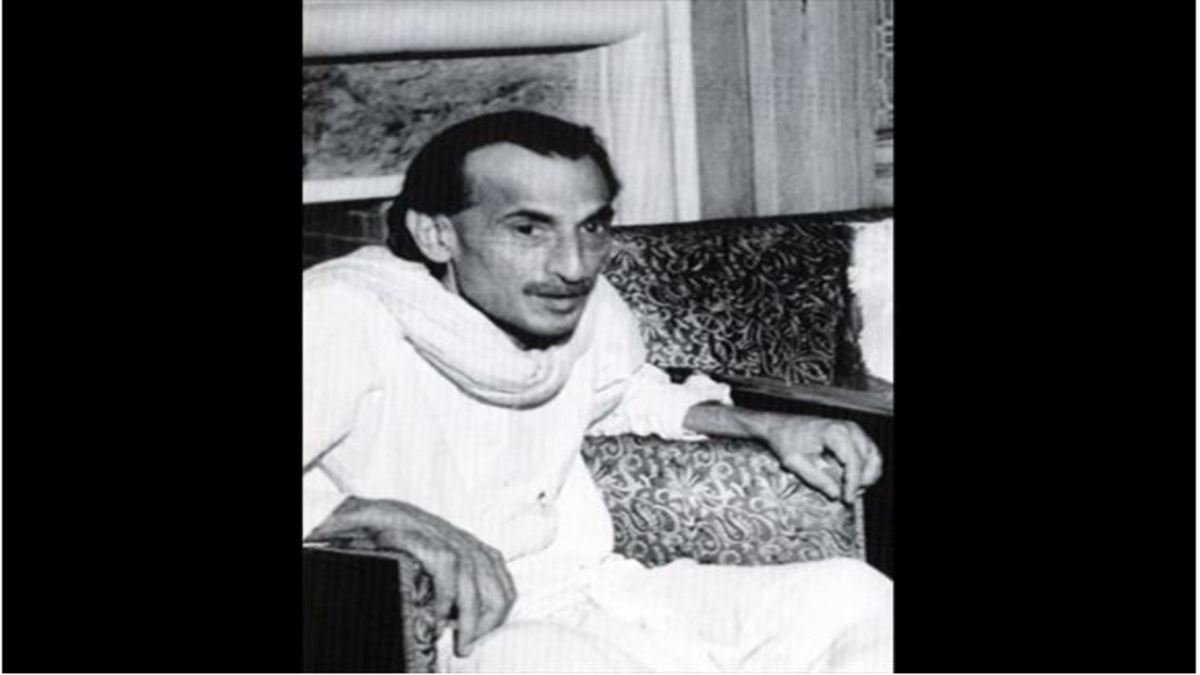

Aligarh: Why should we necessarily commemorate [Acharya] Jiwantram Bhagwandas Kripalani (1888-1982), who shares his birthday with Maulana Azad— November 11, 1888?

The current generation of India’s students and youth are perhaps not as fortunate as their counterparts were in the decades of not so distant past. During the 1920s, they had Bhagat Singh, during the 1930-1940s, they had Nehru and Bose, and after independence, during the 1960s and the 1970s, they had Ram Manohar Lohia (1910-1967) and Jai Prakash Narain (1902-1979).

JP and Kripalani fought against the ‘dictatorial’ behaviour of Indira Gandhi (1917-1984), and against her infamous Emergency which she imposed on June 26, 1975. During the Emergency era, the press had been silenced, whereas, many tend to look at the current dispensation as worse than that, because, sections of the media in this era are seen to have sold themselves out to the corporate, hands-in-gloves with the anti-poor and anti-minority regime today.

This muzzling of dissent is assuming alarming proportions with the spurt in fake news, spread not only through social media but also through some of the popular TV news channels, that are also indulging in spreading hate and prejudice. Faced with huge unemployment, growing economic recession, and deepening social inequalities, sections of youth are resorting to lynch gangs and subscribing to muscular exclusionary nationalism.

Latest instance of such lynching and majoritarian violence manifested in the town of Sitamarhi in north Bihar where a 70-80 years old poor backward Muslim, Zainul Haq Ansari was lynched and burnt to death by a mob going to immerse the Durga idol on October 20, 2018 (see my piece, The Wire, November 6, 2018). This happened in police presence.

Despite a long history of communal violence, on Durga Puja and Ramnavmi, in Sitamarhi-Sheohar (bordering on Nepal; till 1972, it was a subdivision of Muzaffarpur), and despite mounting tension and fear on the night of 19 October, there was sordidly inadequate police deployment. (https://hindi.newscentral24x7.com/tag/sitamarhi-mob-lymching/).

Even the most liberals of the national English dailies, with high circulation in Bihar, kept itself unaware of this mob barbarity, for weeks.

Irony

It may look ironical that Sitamarhi, having become infamous for one of the most riot-prone regions of Bihar, was one of the first Lok Sabha seats to have elected a non-Congress member. It was none other than the grand Gandhian-Socialist, J. B. Kripalani. He was elected in 1957 as a nominee of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP). Nehru, in order to ensure his victory, had not fielded a Congress nominee against him.

It was also one of the first seats to have elected an OBC candidate, Nagendra Yadav, in 1962 (also re-elected in 1967). Notwithstanding its educational backwardness, thrice, Sitamarhi elected academic parliamentarians—1957, 1977, 1984—Prof. Kripalani, Prof. Mahanth Shyam Sundar Das (son-in-law of famous Hindi writer and socialist Rambriksha Benipuri, 1899-1968), and Prof. Ramshreshtha Khirhar, respectively.

The life of Kripalani, a “Congressman, Gandhian, Socialist, parliamentarian, and writer, spanned almost a century. As a young man he saw the rise of Mahatma Gandhi to centre stage in Indian politics; and in old age, the fall of the Janata Party government from power. A social and political activist for some seventy years, at no point, did he ever compromise his views or principles to suit those who were in power, or to curry favour with them”, says T. N. Chaturvedi, in his foreword to Kripalani’s thick autobiography, My Times: An Autobiography, published posthumously in 2004.

From 1912 to 1917 he served as a professor of English and History at the College in Muzaffarpur, later named after Langat Singh (1850-1912). It was there, Kripalani became the host of Mahatma Gandhi in 1917 when he was en route to Champaran for the famous Satyagraha against the European planters. Because of this association, Kripalani was jailed.

Subsequently, he taught at BHU (1919-20) and was Principal, Gujarat Vidyapeeth, 1920-1927. During 1934-45 he was General Secretary of the Congress, and in 1946, he became the President of the Congress.

Kripalani was first ever member of independent India’s Parliament, to have moved the no-confidence motion on the floor of the Lok Sabha, in August 1963, immediately after the Sino-Indian war.

In 1950, despite Nehru’s support, he was defeated by Patel’s candidate Purushottam Das Tandon, for the post of Congress President. After this defeat, he left the Congress and was among the founders of the Kisan Mazdoor Praja Party (KMPP). It eventually merged with the Socialist Party and became Praja Socialist Party (PSP). His wife, Sucheta, however, continued with the Congress, and having served as Union minister in various portfolios, also became first female chief minister of Uttar Pradesh.

Having asserted against what he called Indira Gandhi’s authoritarian rule, since 1971-72, he was among the first to be arrested on June 26, 1975, when Emergency was clamped.

His thick volume of memoir testifies his critical engagement and encounters with Gandhi. “He was willing—keen, in fact—-to be Gandhi’s soldier, but disciple? No, thank you”, says, Gopal Krishna Gandhi (The Wire, August 15, 2016). His engagement with Nehru too was critical. He left the Congress on a principled position. Nehru maintained that the President of the Party (Congress) should not interfere into the everyday affairs of the government.

Kripalani’s memoir also scrutinises Maulana Azad’s account about partition in his ‘India Wins Freedom’ (pp. 183-184), where Azad sort of blamed Nehru, Sardar Patel, and even Mahatma Gandhi. Kripalani has devoted a whole chapter, “Setting the Record Straight” wherein Kripalani asks (p. 691), “why Maulana himself was silent about it in the Working Committee. Why did he not raise his voice of protest there as Ghaffar Khan did? If he had, and the two had been joined by Dr. Syed Mahmud and Asaf Ali, in opposing Partition, they would have been four and they would have had the powerful backing of Gandhiji”.

Against Corruption and Authoritarianism

From 1967 to 1977, he kept working for an anti-Congress united coalition. During the Emergency, he openly criticised Indira, led public demonstrations, and in 1977 he wrote that ousting a dictatorial regime indicated growing political consciousness, and that “those who said that freedom is required only by intellectuals and the cultured few have been proved wrong. It was required by the many, the poor, and the despised in India”.

In 1950, Kripalani also launched a weekly, Vigil. “Its main objectives were to educate the people to insist that the authorities should adhere to the broad policies and programmes of Gandhiji and to raise their voice against corruption in the administration and the rampant black-marketing and tax-evasion in commerce”, which was disliked by Sardar Patel, who tried to prohibit its reproduction by other newspapers (pp. 735-737). It ran for a decade.

Communal Violence

The above quick and synoptic recounting of Kripalani’s engagement with almost every social, economic, and political issues, one is surprised by the fact that his memoir is almost completely silent about the communal violence. This is even more surprising because one of the most heinous communal violence took place in Sitamarhi in 1959 when he was actually representing this seat in Lok Sabha. Of all the north Bihar districts, Sitamarhi-Sheohar, part of the then Muzaffarpur district has historically been most prone to communal violence. In fact, an earliest recorded communal violence of Muzaffarpur was in 1895 in a village Mathurapur (Sheohar).

On 9 January 1941, on the day of Baqr-Eid, there was a Hindu-Muslim clash at Rakasiya tola, Rampur Runi, Belsand thana (Sitamarhi), in the then Muzaffarpur district. A ‘furious Hindu mob’ of about 10,000, with deadly arms, had assembled to prevent cow sacrifice which was supposed to be done in the village secretly, they also set some houses to fire, ‘the situation had taken a serious and dangerous turn’; Muslims had also collected similar arms, and one of them had fired gun-shot injuring few Hindus; the Subdivisional officer and a police inspector arrived at the spot, when their warnings and persuasions to disperse the mob had failed and the inspector had received injuries, the police had to open fire in which some people were injured.

On 25 October 1947, at Singha Chaouri (in Pupri, Sitamarhi), there was a communal violence, in which, according to the then Commissioner (Tirhut), Ekbal Husain (aged 70) was killed; On 27 October 1947 the Commissioner informed the Chief Secretary about communal tension (over cow sacrifice in Bakrid) in the villages of Bajpatti, Hussaina, Mehsaul. In these riots, there were also instances of ‘poor class Hindus showing courage and humanity in sheltering the families of the Muslim residents’. These Hindus were recommended by the Commissioner to be awarded suitably by the Government. Compensation to the Muslim sufferers was also proposed.

In 1948, there was a communal violence in Belsand (Sitamarhi), over a dispute regarding the Mahabiri Jhanda procession, and then on 17 April 1959 another riot broke out in the town of Sitamarhi, killing as many as 50 persons, mostly Muslims. A false rumour had spread in cattle fair that a cow had been slaughtered, whereas the cow was subsequently recovered from Janki Asthan.

Nehru, having visited Bihar and having addressed ‘several major meetings’ wrote, “The rumour [of cow slaughter] could not be correct because it is hardly conceivable that any Muslim would do such a thing in the middle of a huge Hindu fair. Probably, some mischief makers started this rumour… The next day, at Akhta, a Muslim village nearby…organized attacks [took place], 200 houses …were set on fire”. Again on the issue of cow slaughter, in which 11 people, mostly Muslims, were killed and 200 houses were burnt. [The village Akhta had suffered a riot in 1934 also]. Nehru, the Prime Minister, was particularly puzzled as to how easy it was to excite people. He, however, expressed his satisfaction at swift administrative action to contain the violence. He added, “it is interesting to note that in the Muzaffarpur district where this communal trouble took place, the District Magistrate is a Muslim. Also, of course, the Governor of Bihar [Dr Zakir Husain] is a Muslim, and so is now the President [Abdul Qaiyum Ansari] of the [Bihar] Pradesh Congress Committee”.

On 13 October 1967, again a riot took place in Sursand (also a Community Development Block and thana headquarters of Sitamarhi Subdivision of the then Muzaffarpur district), claiming 50 lives and 400 houses were burnt to ashes.

The then Congress MLA of Paroo, Muzaffarpur, Nawal Kishore Sinha (former minister and the then General Secretary, Bihar Congress, and Member, Central Relief Committee) made a statement on 16th October 1967 that this riot was the handiwork of the Jana Sangh, the political outfit of the RSS. Joginder Prasad Thakur, in his deposition before the Enquiry Commission, said that the shakhas (units) of the RSS-Jana Sangh had been spreading in the region since 1957, adding to the communal tension. It was also found out in the enquiry, with reference to the CID report that the ‘local leaders of the Jana Sangh, RSS and a section of the Congress had preconceived and pre-planned these disturbances.’ In this particular riot, 50 people were killed and 400 houses were burnt. In Sursand, on the southern bank of a big pond, there was a mosque, but a statue of Hindu god, Shiva was forcefully put into it.

Consequently, the mosque was shifted to the eastern bank of the pond. Thereafter, the RSS started its stick-parade on the bank of the pond. Communal tension compelled the administration to intervene and the stick parade of the RSS was banned. Subsequently, the tension reared its heads again when a dispute arose on the issue of passage for Hindus through a Muslim graveyard (Qabristan). [This dispute dated back to 1959. In 1965, with the Indo-Pak wars, the communal tension had increased, yet, the administration did not do the needful, as found out by the official enquiry]. It is said that it was mainly due to prompt intervention of the Superintendent of Police, Muzaffarpur, S. F. Ahmad that the spread of the riot could be checked.

In early October 1992, again there was massive communal violence on this very issue of Durga idol immersion route in the town of Sitamarhi; it spread in the village of Riga (details in my book on Muzaffarpur Muslims).

Sadly, despite, such a long history of communal violence, police deployment and preparedness to prevent the violence was glaringly inadequate! Lalu Yadav, the then chief minister did handle it firmly. But he did not institute an enquiry to book the culprits. S. R Adige, IRS, was supposed to inquire into the 1992 violence. Some Communist leaders in Riga were brave enough to have saved many lives.

To the best of my knowledge, there have not probably been adequate researches on Kripalani. It needs to be explored if he really made any significant intervention (inside the Parliament or outside) on the communal violence post-1947, particularly in Sitamarhi (which he represented in 1957-62). Or, did he just forget the people who elected him?

In an era when many Socialists and crypto-Socialists tend to switch over to the hate-mongering ideologies, resurrecting and commemorating the legacies of the likes of Kripalani is all the more necessary and relevant to rescue India and its pluralist-inclusivist nationalism.

The misguided youth of today, trying to build their quick political career by subscribing to divisive ideologies, should be persuaded to look upon the rational and independent thinking icons such as Kripalani.