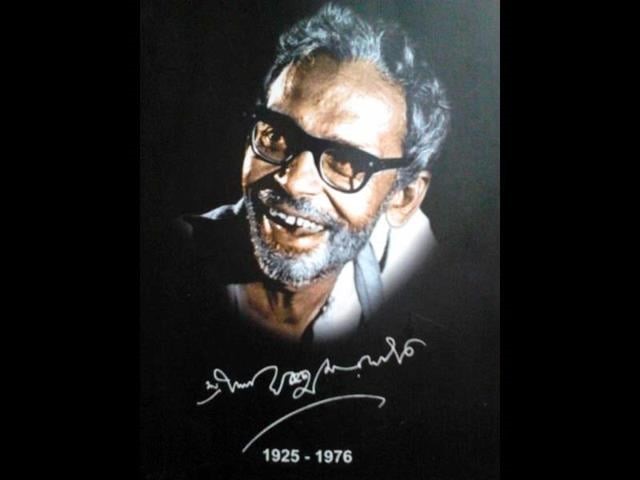

Ritwik Ghatak, born in 1925 in British India, was not just a filmmaker; he was a visionary whose path breaking experiments left indelible mark on the footprints of Indian cinema. His contributions, both as a director and a scriptwriter, showcased a unique fusion of realism and symbolism. On November 4, we commemorate the birth centenary of this cinematic genius.

Ritwik Ghatak films (Ghatak’s filmography) is a treasure trove of cinematic brilliance, transcending unexplored horizons, to reinvent contemporary Indian art. Each film is an intensive exploration of complex human emotions against the backdrop of socio-political realities, reflecting the turbulent times in which he lived.

He was an individual with a characteristic and independent working style, and one of the mascots of the parallel cinema. He also waged a rebellion against a national cinema whose conventions he wanted to make a major rupture from with each of his work.

Ghatak’s life ran parallel to some of the most traumatic periods in the 20th century India, which had a major bearing or influence on the course of his work. He was a product of the convulsions of the 1940s – World War II, the terrible “man-made famine” of 1944, the communal violence that came with independence, and especially the partition of Bengal.

Characteristics of Ghatak Films

Ghatak’s approach to filmmaking had autobiographical overtones and often reflected his personal experiences. He would experiment with narrative structures, visual aesthetics, and sound design, creating films that were not only intellectually appealing but emotionally vibrant. His works manifested a commitment to truth, a deep empathy for his characters, and a keen sense of social justice.

Ghatak used the theme of alienation to manifest harsh truths of human experience under oppressive social and economic systems. His work expressed a form of cultural resistance against foreign domination, utilising myth and epic to examine cultural conflicts and the fragmentation of Indian identity in the post-colonial era.

Marxist ideology fundamentally shaped his work, his films cantered on the lives and struggles of ordinary people, both rural and urban, particularly the trauma of the Bengal partition. Ghatak’s Marxist perspective was expressed in his critique of the bourgeoisie and his portrayal of characters who, despite facing adversity, manifested a resilient human spirit.

Ghatak believed that exploring the collective unconscious through Jung was essential for exploring the inner world and that it complemented his materialist, Marxist analysis of social and political reality. His films, especially his “Partition Trilogy,” used Jungian archetypes, symbolism, and mythologies to explore and manifest the collective trauma and rootlessness of the Bengali refugees.

Ghatak did not see a contradiction between Marx and Jung, but rather as different ways of interpreting the human condition. He diagnosed that the collective unconscious affects unconscious behaviour, while class structure determines conscious behaviour.

What distinguishes his work was a deep engagement with the human psyche and an unapologetic exploration of societal issues. His subjects repeatedly projected the uprooted and the dispossessed: parentless children, homeless families, disoriented refugees, and the petit bourgeoisie, economically broken by their exile. With touches of artistic genius, he invokes glimmer of optimism in even the darkest adversity

The ability to fuse stark reality with poetic symbolism symbolised a constant struggle, against an age and society which sold itself to the shackles of rampant modernization, and against a national cinema whose conventions he wanted to make a rupture with in each of his works. His films exude sense of emptiness, giving us a feel of what it is to be alienated from one’s roots.

Ritwik Ghatak‘s work is a concoction of socialist ideology with a deep critique of post-partition India, focusing on themes of trauma, class struggle, and the commodification of culture. His female characters, epitomise both specific Indian experiences and universal human struggles against systemic oppression.

Influences in Early Life

His father, Rai Bahadur Suresh Chandra Ghatak, a magistrate in Mymensingh and Rajshahi districts of east Bengal, instilled in him the love for Sanskrit classics, the Vedas and the Upanishads, which often formed an integral theme in his films. In 1942, he was brought back from Kanpur to Rajshahi.

Involved from an early age in politics and in theatre, Ghatak was a member of the Indian Communist Party and considered Brecht and Eisenstein his role models.

He promptly submerged himself into the 10,000 books in the public library of Rajshahi. He was driven by and cultivated a love for the anti-Fascist movement of World War II which included Marx and Lenin. He later read a great deal on archaeology, on the Buddha, he examined the works of Jung, especially his psychology of the collective unconscious. The films he made between 1956 and 1966 bear powerful hoof prints of his deep and obsessive study of these books.

Best Films

It is interesting to note that despite being referred as the most creative artist in the area of filmmaking that India has produced, he only had 8 full length feature films to his credit. This speaks volumes of the impact that his 8 films made in comparison to the tons of films made by his contemporaries.

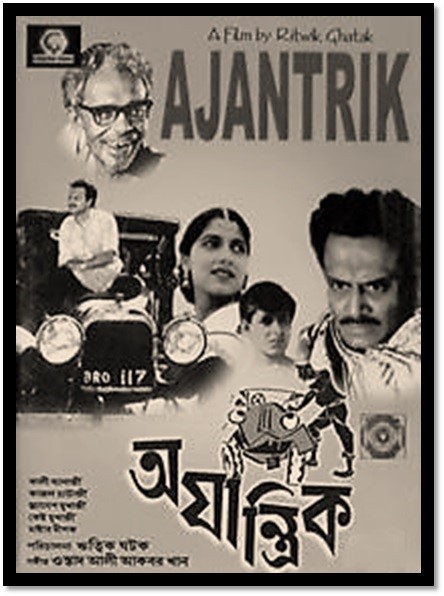

Ajantrik (1958) is a cinematic essay on the acceptance of the machine into the mental make-up of someone embedded or rooted in an ancient and totally un-mechanical tradition. Ajantrik it is a ramshackle taxi driven round the town of Ranchi on the Bengal-Bihar border by an eccentric peasant called Bimal. The taxi is a target of ridicule to most who see or drive in it, but for Bimal it has a human character which is alternately jealous, loving and uncaring. Thus it breaks down when Bimal is attracted to a stranded girl. At the end of the film, with the taxi’s death caused by a betrayal, the machine seems more reliable than its human counterparts.

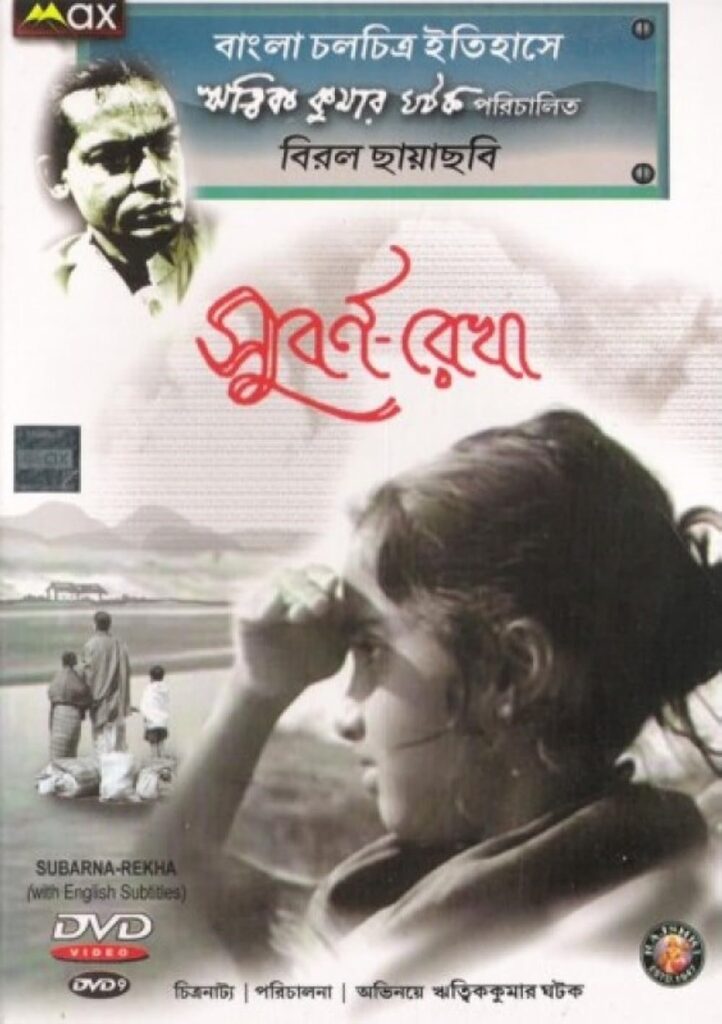

‘Meghe Dhaka Tara’, ‘Komal Gandhar’ and ‘Subarnarekha’ form the famous trilogy, portraying the complicacies of the refugee families from the erstwhile East Pakistan.

Meghe Dhaka Tara (1960) (or ‘The Cloud-Capped Star’), is the most captivating portrayal of a harsh life in Bengal following the dreaded partition highlighting the atrocities experienced by the refugees. He used music and sound with magical effects. This film is, a ruthless, stunningly bold critique of the family as an institution.

The central character is Nita, who virtually sacrifices her life to keep her family afloat even when she realises that the man she loves, and who professes to love her, is about to marry her more sensual sister. All this is witnessed by Shankar, her musician brother who eventually leaves home, returning to find Nita in a sanatorium. In the film’s last scene, with the singer brother visiting Nita in hospital, the warning vibrato of a Pahadi folk song can be heard before he enters, as we witness the beautiful countryside around the clinic. Nita, sobbing, says to him: ‘Brother, I want to live. I want to live.’ For Ghatak, sound and music often became synonymous, with such scenes forging a perfect synthesis.

Also known as A Soft Note on A Sharp Scale, Komal Gandhar (1961) is the second movie in the Ghatak’s trilogy after Meghe Dhaka Tara.

Along with revolving around the theme of the Partition, the movie also is a narrative of a star-crossed couple and the rift that split apart the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). ‘Komal Gandhar’ explored three interconnected themes, Anusua, the lead character’s dilemma, the infamous divided leadership of Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA) and the tragic fallout after the partition of India. Unlike his other works, this one ends with the lead pair (Vrigu and Anusua) being reunited ultimately.

Subarnarekha (1965) is the last instalment of Ghatak’s Partition Trilogy. ‘Subarnarekha’ narrates the life story of three refugees in West Bengal: a Hindu man, his little sister, and a low-caste boy. Subarnarekha navigates the lives of a man, his child sister and a young boy whom the man provided shelter after the boy loses his mother in a melee. The film begins in a refugee camp of the then Calcutta, where a number of refugees have assembled in the hope of building their homes afresh. It explores how poverty and homelessness transform an individual’s attitude and his decisions throughout his life. Subarnarekha projects the plight of the three characters, the effects of hardships on shaping their thoughts, actions and the very paths they pursue in their lives. It is a tale of darkness and despair at its zenith. It conveyed that there was no political answer to Partition and that the resulting spiritual confusion could not easily be resolved.

The deep sense of waste is sharply expressed and the film itself Ghatak’s most brutal description yet of the social consequences of a political act. The female protagonist, Sita, symbolises a political uprootal. Ghatak restores the imagery of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland in this film. Ghatak’s ‘wasteland’ is Calcutta and Sita is the ‘waste’ within it. The wasteland of Calcutta forbids Sita the freedom to live up to the mythical name she was christened with. She cannot accept this reality when she discovers that her ‘client’ is none other than her brother Ishwar, who ‘mothered’ her. Sita’s suicide makes a statement of protest against the dehumanisation of values in a modern, plagued society. Nevertheless life resurrects for the hero of the tragedy, with his sister’s child looking forward to a better life on the banks of the Subarnarekha River.

Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (1973 was originally an epic novel based on the tragic lives of a fishing community in the valley of the River Titus, Bangladesh. The film resurrected Ghatak’s obsession with the female principle, navigating the life and ultimate dissolution of a fishing community on the banks of the river Titash in Bangladesh. The river starts drying up. Death and starvation endanger the lives of the fishing community. Urban vested interests exploit the situation. The fishermen are displaced, and Basanti alone stays back, remaining a live witness to and victim of the incident. It featured multiple characters in a conglomeration of interconnected stories. The film is a powerful parable about the destruction of a traditional Bengali fishing community striking an analogy with the displacement caused by the Partition of India. A poetic film that portrays the life of a fishing community along the Titas River to navigate realms of cultural decay, memory, and fate.

In his final film, Jukti Takko Aar Gappo: (1977) Ghatak played an alcoholic, disillusioned intellectual who comes into contact with Naxalites. The film explores the political and social realities of Bengal in the early 1970s. The film lacked any specific political ideology, navigating the story of an intellectual’s crisis and the isolation he experienced from society. The film is a deeply personal political statement, playing a pioneering role to project the crystallizing of Naxalite movement just taking shape in Bengal.

(The author is freelance journalist; he acknowledges the sources for this article: Times entertainment, Shoma Chatterji in ‘’High on Films’, Shreya Biswas in Indiatoday.in, Philatelyhobby.blogspot and Shoma Chatterji in Hindustan Times)