When asked about his focus on the past, in a conversation with the artist Iman Essa, filmmaker Amit Dutta says, “I think it’s the duty of every artist who comes from a colonised country to get in touch with their instincts…the idea is not to interpret or celebrate the tradition but to use it to get in touch with our reflexes, the inner layers of our own minds which are made of all this. It’s very important to state that it’s not and should not be a regressive project.”

The observation is striking in its unpeeling of the impulses that lead artists to a study of the past. For often, the artist relies only on these reflexes, these impulses to guide him through the creation of a work. But this looking back at distant pasts is to walk into a labyrinth, especially in these times, when mystification of the past serves as a useful political tool to control the present. A master key is required, or a khevat/ oarsman as it were, to help us navigate the choppy waters.

My first encounter with Prof. BN Goswamy, BNG henceforth, incidentally came through a cubist portrait of the great man drawn on film by Amit Dutta in his Museum of Imagination. It is, as Dutta writes in the beginning, a film made of silences. Until the final third of the film, the man in question is present mostly in his absence or seen from afar, through window-panes, sitting outside holding a thought in his hands, his back to the camera. We see the famous cravat around his neck as his hands wave about in conversation but the face remains unseen, the baritone remains disembodied. A home is seen – a comfortable home resplendent with books and bronze statuettes, Warli murals painted on the walls, a garden with remains of ancient columns. He begins to speak of his childhood but the sentence remains tantalisingly incomplete. A shadow is seen on the wall, soon to vanish.

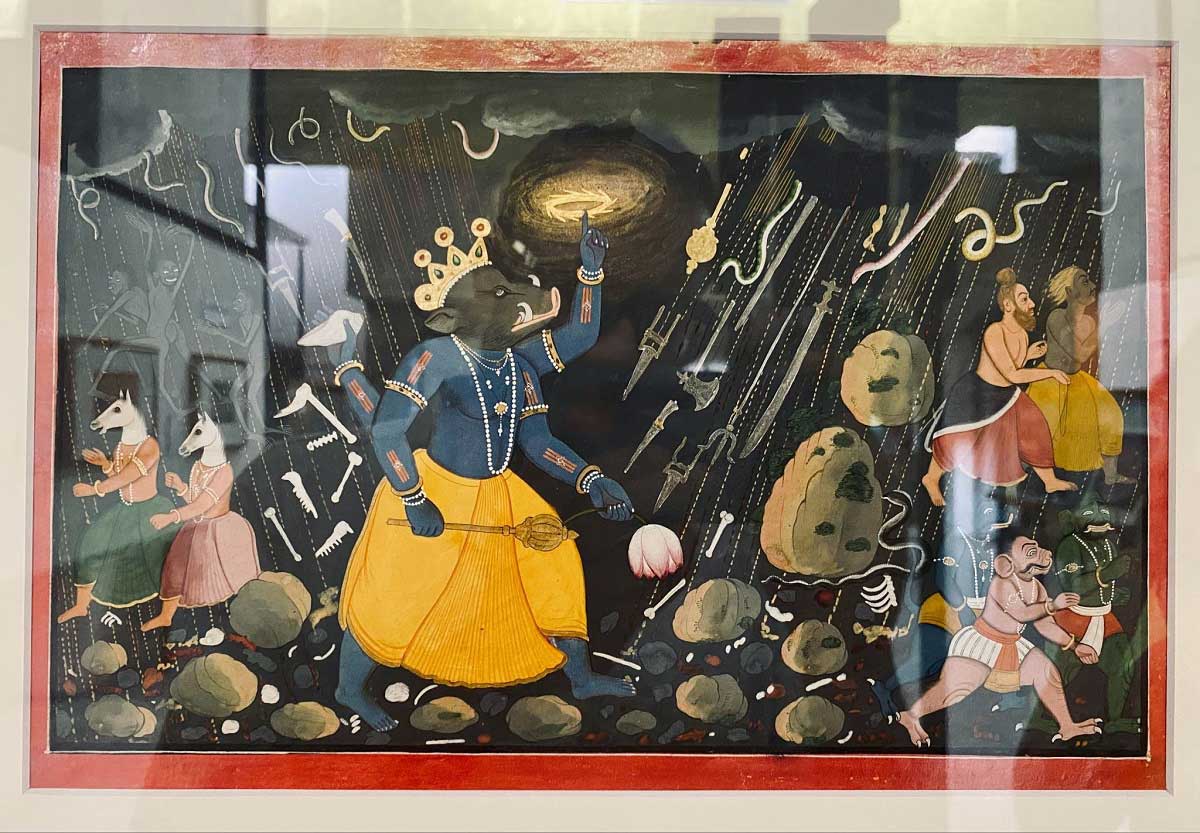

It occurs to me that we are looking at BNG like he must have looked for the great Pahadi painters hidden behind the shadows of time. This cat and mouse goes on until we find BNG sitting with a book in a walkway at the Museum of Fine Arts, Chandigarh, as if an actor is sitting on stage. What is going on in his head? A little later, in the reference library of Chandigarh’s Government Museum and Art Gallery, BNG sits with an unopened folio in front of him. As the painting is unwrapped, the oilpaper covering it is pulled back, a storm gathers, thunder cracks sharply in the sky, the lens focuses on a whirling chakra – this is the ‘Emergence of the Varaha’ – we are inside the museums of BNG’s and Amit Dutta’s and great Eighteenth century painter Manaku’s imagination.

The ‘Emergence of the Varaha’ is on display at Chandigarh’s Government Museum and Art Gallery. At first the painting’s small size confounds; it is afterall a miniature, meant to be held up almost like a photo-album. But much is gained, as BNG says, in moving inside the picture in a ‘leisurely fashion, lingering over each nuance’. Seen closely, the exquisite craftsmanship of the mussavar becomes apparent – the gold in the chakra, shimmering. Coils of snakes dropping from the sky, black storm clouds of terror raining blood pus and bones, the fleeing from the battlefield of saints and demons; even a strangely delighted ghost – and at the centre of it all, the narrow-eyed, boar-faced Varaha, slayer of Hiranyakashya, saviour of the Earth, standing tall. In his Spirit of the Indian Painting, BNG writes,

‘One can almost sense the very heavens shake and tremble with sounds that fill all quarters, and a shower of weapons falls from the sky…All this while, Varah stands firm, feet solidly planted on earth…Stillness in the midst of commotion, the good standing firm against evil.’

Between Dutta’s use of sound and BNG’s words, Manaku’s work comes alive.

Learning how to look is also, in essence, changing how one thinks. Knowledge makes the hitherto unseen visible even as it throws new light on all that’s relegated to the back of the mind. A transformation has occurred inside me. I am suddenly seeing Varahas everywhere.

In Lucknow’s State Museum, itself a relic, I come across a massive Yajna-Varaha hidden at the end of a claustrophobic bhulbhulaiya of exhibition-rooms and passages. The imposing, exquisitely crafted tenth-century sculpture from Jhansi evokes fear and respect – in no little measure to convey the might of the avatar, but also reflecting perhaps the sculptors experience of encountering a wild boar (the words boar and Varaha come from the same proto-Indo-Iranian root). On its body are etched rows upon rows of Rishis and Gods and Goddesses being rescued from the primordial waters. On his snout sits Saraswati, on his back Brahma. Under him snakes the Shesh Nag, signifying the waters under the Varahas feet, and from which it has just rescued the earth, which now in the form of its consort Bhudevi, hangs on for dear life from his right tusk.

The Varaha was most certainly a totem of the forest dwellers who would’ve marvelled at the solitary wild boar’s speed and power, which when enraged, could take on a tiger. As these hunting-gathering tribes passed into the caste system, their totems were amalgamated into the vedic Hindu canon, where incidentally it was originally a form of Prajapati or Bramha. With the rise of Vaishnavism, the Varaha became Vishnu’s third avatar. In the Gupta period, with its patronisation of Brahmanism and Vaishnavism, Varaha worship proliferated. Majestic statues and carvings and even temples have been found in important Gupta (and post-Gupta) centres of Eran, Udayagiri, Khajuraho, and Jhansi among other places.

A magnificent tenth-century Varaha from Sunari, Vidisha is being hosted at Mumbai’s CSMVS (Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya), a part of its ongoing exhibition titled ‘Ancient Sculptures’. It is remarkably of the same size and make as its Jhansi/ Lucknow Museum cousin, indicating perhaps a continuity and even standardisation of sculpting.

Continuing with my Varaha spotting streak, at a small but well mounted exhibition of archaeological finds organised by the Mumbai university and Sathye college, I found a much smaller, eleventh-century statue of the Varaha.

The rows of figures on its body are gone, the sculpture has shrunk to the size of a small animal, more a wombat than a boar. The Varaha seems more ornamental than central to worship. Excavated from an ancient temple complex dedicated to Vishnu, the Varaha worship already seems to be losing its importance, at least in this region.

But there are other survivals. At CSMVS, in the corridor leading away from the central hall at CSMVS, I encounter a female-bodied, boar-headed sculpture. A short inscription describes it simply as tenth-century Varahi from Gujarat.

In a remarkable series of miniatures invoking the Tantric goddesses, attributed to Kripal from Nurpur, called the ‘Tantric Devi’ series, Varahi is seen as a ten-handed Goddess riding a tiger. She holds in her hands an assortment of weapons but also the kapala – the bowl she drinks liquor from, which can also be noticed in the CSMVS Varahi statue’s left hand.

On the Devi’s face is painted a determined ferocity – even the male tiger underneath her, his tail twitching in the air in anticipation of danger, pales in comparison. No less than the sun itself makes a halo behind her. The luminescent stones in her crown and jewels catch our eye – iridescent Beetle wing cases used to stimulate the appearance of emeralds. BNG calls these paintings the ‘visual counterpart of concentration’ known to Tantric devotees. The ‘meditative verse’ on the back reads:

I worship in my heart ten-armed Varahi, whose lotus eyes quiver from spirituous liquor, whose face is like the sun’s rays, seated on a tiger!

Varahi is known to be one of the fiercest of the saptamatrikas or seven mother Goddesses of the Shakti cult (sometimes ashtamatrikas) found both in Hinduism and Buddhism and are definitely borrowed from the more ancient Tantrism – itself born out of the practice of ‘Mother-right’ rituals and magic as Debiprasad Chattopadhya argues in the Lokayata, his seminal work on Indian materialism. These rituals, considered to be precursors of organised religion, in turn can be traced to prehistoric agricultural rites, practised by women to ensure a good sowing season. Even now, thousands of years later, in the vast majority of Indians with links to agriculture or land in some form, by being dependent on it or in ancestral memories, a form of devi-puja is common.

The cult of Mother Goddess can be seen in the Indus valley seals, in the name for tantra ‘vamacharya’ (women – path) and in its appropriation as counterparts to male Gods by Puranic Hinduism. And while Varaha worship has completely ceased, Varahi-mata temples are very much in use and are found in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha. The demise of a royally-sanctioned Vaishnav tradition is not an impediment to the continuation of a more ancient cult.

India is a country of long survivals, says DD Kosambi – that other great teacher of the historical method. The past lives on in the present. It percolates, upwards through layers of archeological time, in the palimpsests Nehru spoke of, in the lives of the ordinary Indians around us. We only need to look closely. Deedar ka samaan chahiye. These departures and arrivals of ideas, eddies of time, similar to primordial waters of the Hiranyagarbha as Manaky once painted, swirl around us, inviting us to probe further and make connections.

The eighth century Kashmiri poet and critic Abhinavgupta describes a sahridaya, used often by BNG, as:

‘one whose heart has been made transparent, like a mirror by constant chewing of poetry and who is thus able to become immediately one with the emotion portrayed.’

Through BNG’s ‘chewing’ of the Pahadi masters’ work and Amit Dutta’s ‘chewing’ of BNG’s work, the lives and works of great artists are illuminated for us. Their art flows through disparate, utsahit hearts, drawing into its embrace sahridayas across yawning gaps of time.

But with only a smattering of methods gleaned from the masters, one wanders through corridors of history, knocking at locked doors, picking up shards of broken pottery and peering into illegible portraits of men and women whose names are now lost in the fog of time. Who were these artist-ancestors of ours? What impulses drove them to pick up the brush?

In 1969, BNG, delivered a lecture on ‘Indian Painters of the Punjab Hills’ at the Royal Society of Arts, London. At the end of what was already a deep insight into the lives of the Pahadi painters, he does something unusual and tries, ‘..to reconstruct an imaginary day in the life of a Pahari artist..’. Slowly, with great care, he paints an image of a master artist going about his daily chores – zealously protecting the fingers he paints with, negotiating with creditors, conferring with other artists, receiving a new text on the erotics brought by the village pandit, inspecting his meagre lands, speaking to his tenants while mentoring the next generation of artists. Technical details are deftly weaved within the narrative – twigs of the basuti bush are used to make pencils, bright red hue is made by drying and crushing of insects gathered from cactus leaves, brushes are made of squirrel tails, a student grinds the yellow peuri colour, another burnishes a finished painting with ‘highly polished mortar-shaped agate’; But as the day proceeds, the artist is weighed down by the challenges of making ends meet. Anxiety besets him. He hasn’t yet conjured up the drawing he must make for the rani’s birthday. Now BNG unfurls, in his signature style, a brilliant epilogue:

‘Images flit into his mind and are expelled: a tumult is building up; and then, while the mind grapples with the task of selection and rejection, it holds on to one series of images…The search is now over: the master’s mind is made up…. as the night thickens around him, the master puts the prayer-book aside and, sitting cross-legged, closes his eyes, in the effort to concentrate. After a while, the mind stops wandering, becomes sthira like a silent lamp burning in a windless place. All becomes clear at last : no shadow separates the thought of the image from the image. It is at this point, when all is still both outside and inside, when the time is quiet and nothing stirs, when the faint glow of dawn begins to light up the distant rim of the sky, that the master takes out his materials from the wooden box. He bows to the brush and then holding it steadily in his hand moves it on the surface of the paper ever so softly, with so light a touch that the brush seems to be breathing over the paper. The great and gentle task has begun. Another masterpiece is on its way..’

With characteristic sensitivity BNG parts the curtains of history and brings forth on stage an Indian artist, hitherto unknown. He looks deep inside a painting, finding the artist in each stroke of his brush, discerning hints of his inner world spread throughout the canvas. He then looks away, delves into poetry and scriptures, looks into the ‘stern pages’ of the bahis, to resurrect the portrait of a great master, who, grappling with the difficult questions of life itself, faced with mortality, ‘relegated’ to a carpenter by caste society, chooses to be guided by the reflexes within. He is moved by the small and great things around him, the flowing waters of mountain rivers – elephants bathe in it, kings are cremated next to it, by the chatak’s mournful call, by the whorled branches of the kadamba tree, associated with Krishna, by the music Raja Balwant Singh is so moved by, by the determined passage of seasons, by the timelessness of the epics, by the evocative scriptures, the mystical world of tantra-mantras, the wandering saints, the bhavasagara that the world is. He is aware of the improbability inherent in creating art. The Devi herself speaks through his work. This is not only Indian art through history, but also history of Indian thought through art.

Gura To Ji Ne, Gyan ki jadiya Dai

The Guru has given the roots of knowledge

In BNG, we, the untaught, found a teacher. He lit inside the hearts of some of us, the lamps of knowledge – a way of seeing. And the wax of our ignorance slowly melted away. Through the hearts of rasikas and sahridayas, artists, historians and patrons, the rivers of Indian art flows, in the work they do, past and present collides and the tide of history advances. And when its many secrets, kept alive through invisible webs, are revealed by an extraordinary guru, the roots of the knowledge tree deepen by a few inches more.

Suhel B is a writer and filmmaker