Korea (Chhattisgarh), Keonjhar (Odisha): One day in the summer of 2016—Babulal Salaam does not recall the exact date—workers arrived at this Gond tribal’s farm in Thaggaon village of northwestern Chhattisgarh’s Korea district. They began marking boundaries in limestone around his land and pounding in roughly hewn, lemon-yellow cement pillars. “I asked them what were they doing on my land, but they spoke in a language not from here,” Salaam recalled to IndiaSpend. The labourers marked the farmlands of 35-40 households in all, without explanation, according to the village sarpanch, Ashok Kumar.

Conflict simmers between Adivasi communities and the state, as authorities have earmarked more than 4,000 acres of farms and common property lands—an area larger than 3,000 football fields—for a tree plantation project in 16 villages of Korea district in the mineral-rich state of Chhattisgarh. The project will undertake ‘compensatory afforestation’ for the forests that will be cleared for the Parsa coal block in neighbouring Sarguja district, for which the environment ministry gave permission in February 2019.

In the adjoining village of Chhote Salhi, villagers narrated similar accounts. Pannalal Sai recalled the labourers arriving on his land: “’Paudha lagega’ bolay. Kya paudha? Kyon lagega? Rajasthan side ke labour lag rahay thay. Humko aur kuch nahi bataaye. (Trees would be planted, they said. [We asked] what trees, and why? They seemed like workers from Rajasthan. They didn’t tell us anything).”

Salaam, Sai and other villagers eventually gathered that the labourers were marking out their lands on the orders of the district forest department, who planned to fence these in for plantations.

A fierce late-April sun beat down as Sai, a diminutive, soft-spoken man clad in a white shirt and blue-checked lungi, led us out of the family’s cool mud-and-tile home to their land, a rectangular plot of mixed cropping surrounded by a few mahua trees, on which the family grows corn, paddy, sesame, pulses and vegetables through the year. “Land is the basis of our survival,” Sai said, “If the government takes it away for plantations, how will we survive?”

Pannalal Sai and Babulal Salaam are among the scores of villagers who found their lands being forcibly earmarked for compensatory tree plantation in lieu of forests to be stripped for the Parsa coal block. More than 4,000 acres in 16 villages have been earmarked for this plantation project.

In India, projects that necessitate the use of forest areas for non-forest purposes, such as mining and infrastructure projects, are required by law to undertake ‘compensatory afforestation’ (CA) on an equivalent piece of non-forest land, or double the expanse of ‘degraded forest’ land. In the past, forest departments have largely created monoculture plantations of non-indigenous, commercial species such as eucalyptus, acacia and teak under compensatory afforestation projects. The government counts such plantations as forests. The plantation scheme is a component by which the government maintains that it is increasing forests, thus fulfilling a key commitment under the 2015 Paris Climate agreement to counter climate change by creating carbon sinks.

The compensatory afforestation project pitched in Thaggaon, Chhote Salhi and as many as 14 other villages in the area is related to the recent forest ‘clearance’ (permission) awarded by the environment ministry this February to the Parsa coal block in the adjoining Sarguja district’s dense Hasdeo Arand forests, one of India’s finest.

In all, the project is to sweep across more than 4,000 acres, an area larger than 3,000 football fields, in the 16 villages, impacting hundreds of residents–predominantly Adivasis, or indigenous communities, also called scheduled tribes.

Forest and revenue officials have crafted this project despite the fact that most of the lands in question are being used by the village communities for farming, common property usage such as for grazing livestock, gathering mahua, tendu leaf (used to roll thin cigarettes), chaar (chironji, or Cuddapah almond) and other lucrative forest produce. The land also includes parcels that are rocky (“chattan-waali zameen”), where, villagers pointed out, saplings would not survive.

| Table: Compensatory Afforestation Plan For Parsa Coal Block | |

|---|---|

| Village | Land Earmarked for Plantations (Acres) |

| Thaggaon | 497 |

| Chhote Salhi | 121 |

| Baday Salhi | 657 |

| Baday Kalwa | 275 |

| Dhanpur | 291 |

| Pendri | 194 |

| Bodemuda | 269 |

| Jilda | 237 |

| Majhouli | 101 |

| Bari | 560 |

| Mugum | 639 |

| Chopan | 76 |

| Bharda | 50 |

| Khadgawa | 50 |

| Salka | 57.00 |

| Gidmudi | 82 |

| Total | 4161 acres |

Source: Forest clearance documents for the Parsa coal block, Korea District Office

A questionable offset

A tale of two ‘forests’: In Sarguja district’s Hasdeo Arand, authorities have awarded preliminary clearance for 1,600 acres of dense forests to be stripped for coal mining. ‘Compensatory afforestation’ for this destruction is to take the form of plantations by the forest department in adjoining Korea district.

In Korea district in Chhattisgarh, a forest department plantation of 22,000 trees forms a desolate expanse. The government counts such plantations as forests, and has made them a key component of its international commitments of increasing forest cover to mitigate climate change.

Compensatory afforestation purportedly offsets the loss of forests cleared for industrial, infrastructure or other non-forest projects.

This principle, despite facing serious questions about its efficacy and outcomes, gained heft in 2016, when the Modi government gave it the shape of a law: the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act (CAF Act). The government issued rules for its implementation in August 2018.

To the dismay of Adivasi and other forest-dwelling communities, forest rights groups and opposition political parties, the government brushed aside repeated appeals that the new law be made compliant with the land reforms and decentralised forest governance structures laid down by the landmark Forest Rights Act of 2006, and to ensure that communities in whose villages CAF funds would be deployed would have the right of consent.

In the coming weeks, a fund of Rs 56,000 crore ($8 billion) is set to flow under the CAF Act to state governments’ forest departments. This is money accumulated over the years, based on two components paid into the fund by those who are awarded forest clearance permits: the ‘net present value’ (NPV), or a monetary value put by forest departments to the diverted forest, and the cost of raising plantations on alternative land. Such payments are determined by forest officials, and range from Rs 5,00,000-11,00,000 per hectare, depending on the type and condition of the forest being stripped.

“These huge sums of money are nothing to feel happy about,” a senior Indian Forest Service officer told IndiaSpend, requesting anonymity. “I would call it a kind of blood money – since it reflects how much forests we have lost. And you can never recreate what is being destroyed.”

The challenge, however, is not merely of adequately offsetting loss of forest cover. On the ground, the CAF Act will unleash land conflicts and undermine the resource rights and food security of vulnerable rural communities, particularly Adivasis, our reporting on unfolding projects in Korea, Chhattisgarh and Keonjhar, Odisha shows. These two states are among those that will receive the largest proportion of allocations from the CAF.

A search for land

Over 2014-18, the central environment ministry issued permits to clear 1.24 lakh hectares of forests, according to an analysis by the Centre for Science & Environment. On paper, an equivalent amount of area, or more, has been earmarked for compensatory afforestation. Yet, “Land on such a large scale is hardly lying around just like that,” said Madhu Sarin, a development planner specialising in forest policy and rural communities. “It is all under some use or the other.”

In this land-stressed country, how are the forest departments finding thousands of hectares of land to create plantations? Forest and tribal rights grassroots groups argue that the land is being siphoned off from marginal rural communities, more often than not Adivasis, whose very survival depends on such land.

In November 2017, the environment ministry issued a direction asking states to “create landbanks for compensatory afforestation projects for the speedy disposal of forest clearance proposals.” On May 22, 2019, the ministry further said that in states with over 70% forest cover, compensatory afforestation projects against forest permits need not take place in the same state, but can be housed anywhere in the country, using land banks.

Rural communities say they experience the state’s bid to bank land as a land grab, as IndiaSpend reported on September 19, 2017, in the weeks before the environment ministry issued its 2017 directive.

“Land banks are serving to invisible-ise Adivasi communities,” Gladson Dungdung, an Adivasi author who has written extensively on land banks and forest rights, told IndiaSpend. “In Jharkhand, over 20 lakh acres have been listed in land banks, including common lands, sacred groves and forest lands. People have no clue, and they suddenly find their land and forests being fenced away, cutting off life-giving access for them and their livestock.”

Gladson Dundung (left) during a village meeting on land and forest policies in Khunti, Jharkhand.

The result is “a double displacement”, said Sarin–first for forest clearance, and then for compensatory afforestation.

Parsa coal block’s compensatory afforestation project, which has unfolded over 2016-18, the precise time when the CAF Act and its rules were formed, is a telling example.

“Mahaul garam tha… hungama ho gaya”

In January 2019, the ministry of environment, forests and climate change controversially awarded the Parsa coal block a Stage-I (preliminary or in-principle) forest clearance or permit, setting the ground for stripping 1,600 acres of lush forests for coal mining. The mine has been allotted to the Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Nigam, a state-owned power utility, which in turn has appointed Adani Enterprises Ltd as mine developer and operator, in a move some commentators have criticised as opaque.

The clearance was awarded because the state government showed that a mandatory condition had been met: more than 4,000 acres of non-forest land had been identified for compensatory afforestation in 16 villages in the adjoining district of Korea. This created the impression that forest loss in one site would be made up by planting trees in another.

According to a February 2017 letter by the Korea district collector, submitted as part of the forest clearance application, 1,684 hectares (or 4161 acres) of land which were “free of encroachment” had been identified in 16 villages of Korea. The department, the letter continued, had “no objection” to the land being given to the forest department for CA plantations in lieu of the forest being destroyed for the Parsa coal block.

IndiaSpend travelled to eight out of the 16 villages, and heard a common narrative: villagers said that officials had neither formally informed nor consulted them about the afforestation project. And that they were opposed to such a project, since the lands marked for plantations were privately held or common property land, largely their means of survival and food security.

Despite protests by villagers over 2016-18, officials continued with the plan, which became the basis on which the Parsa coal block eventually secured forest clearance.

A half-an-hour drive from Chhote Salhi is Baday Salhi village, where authorities have marked out 657 acres of land for compensatory afforestation. Residents gathering at sarpanch Ruplata Singh’s home recalled to IndiaSpend how attempts by the forest department to put pillars on farms across the village last year had ended in a skirmish. “Mahaul garam tha.. hungama ho gaya (Things heatened up and it turned into a big fight). We eventually chased them out,” the sarpanch said.

Villagers in Baday Salhi said they chased away labourers and officials who tried to put pillars on their lands for the plantation project.

“They put pillars on our land, right where we do our farming, without asking us, without giving us any information,” said Amar Singh, a villager, “Would we not stop them?” Others in the crowd piped in, “When we asked why here, why not elsewhere, they said they have orders and have to put it where the satellite says so.”

Within days, the villagers uprooted the pillars, threw them away, and resumed farming on the lands. Official documents, land maps and GIS depictions, meanwhile, neatly plot the lands earmarked for compensatory afforestation, giving no indication of these ground contests, or how the land is being used currently.

Korea is a ‘scheduled area’ i.e. a tribal-majority area enjoying constitutional protections, and special laws such as the Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act. The law states that gram sabhas (village assemblies) have the power to manage their natural resources, and must be consulted on any plans regarding these. However, in every village IndiaSpend visited, residents reported that officials had not presented any details of the compensatory afforestation proposal to the gram sabhas for their approval or inputs. “Sab manmani se kiya (The officials did it arbitrarily),” said Thaggaon sarpanch Ashok Kumar of the plantation project in his village.

In Bodemuda and Dhanpur villages, where the forest department has marked out 558 acres of land for compensatory afforestation, sarpanch Shiv Kumar Singh said villagers had a vague idea of what was going on. “The local forester and patwari [land revenue official] came and told me that trees would be planted on our village’s lands as bharpai (compensation) for the forest that would be destroyed by Adani’s Parsa mine in Hasdeo [Arand] on Sarguja side.”

Kumar said he told the foresters that there was very little fallow land available in the village. Of what was fallow, most of it was rocky, and would not be suitable for plantations. “I told the officials that tree planting is a good thing. But it should happen after proper meetings with our gram sabha, so that we as a village can tell them where appropriate land is available, and what species of trees would be suitable,” he said.

Echoing accounts in multiple villages, Shiv Kumar Singh, sarpanch of Dhanpur, says officials have earmarked agricultural land of villagers for compensatory plantations for the Parsa coal block without informing residents.

In Gidmudi village, former sarpanch and current zila panchayat member Gurujlal Neti said the local patwari and forest beat guard had come to him saying they wanted specific lands in the village for afforestation. “I told them that villagers have been cultivating these lands since a long time, and without their permission, how could authorities take it for plantations?” Neti said, “They needed to approach the villagers formally.” The officials left, Neti said, and he thought the matter had ended.

Neti and other villagers were unaware that despite their opposition, officials had gone ahead with the compensatory afforestation plans.

In Bari, sarpanch Jaipal Singh similarly said the local forester, Nirmal Netam, had come to him and said trees would be planted in the village under a project linked to the Parsa coal block. “He gave me some documents in English, and asked me to sign. I did so, trusting him,” Singh said, adding that he thought the trees would make the village greener. It was only subsequently, when labourers came and began digging pillars on villagers’ farms, that the exact plan revealed itself. “Villagers started to oppose it and threw all the pillars away,” Singh said.

On paper, however, district officials have finalised 560 acres of land in Bari for compensatory afforestation. Singh was unaware that this had happened despite the opposition. “When officials tell us something, we tend to believe them in good faith,” he said. “But actually they should be coming and doing proper meetings with the gram sabha, and sharing all details of any proposal with us formally, and in a language we can understand.”

The plan was unlikely to be implemented smoothly unless the villagers cooperated, Singh said: “They [the officials] did not involve us when they should have, and villagers will hardly give up their agricultural land like this for plantations. Jamke virodh hoga (There will be strong opposition)!”

In fact, according to Dhanpur sarpanch Singh, residents were so troubled by the pillars on their lands that sarpanches from several of the 16 villages got together to meet the then legislator, Shyam Bihari Jaiswal, in December 2016 to lodge a protest. This meeting was covered by the local media. Yet, over 2017-18, ignoring what the local communities were saying, the forest clearance file for the Parsa coal block kept moving ahead in the state government and ministry offices in Korea, Raipur and Delhi.

A December 2016 news report in a local Hindi newspaper reports the villagers’ meeting with the local legislator Shyam Bihari Jaiswal to protest against the compensatory afforestation project on their land.

Renewing a historic injustice

The FRA was enacted to redress a “historical injustice”–to recognise through individual and community titles the customary rights of communities that have traditionally depended on forestlands, but whose ties were denied, and even criminalised, by colonial and post-colonial policies. The CAF Act’s letter and design put it in direct conflict with the Forest Rights Act, activists say, shutting out communities and undermining democracy all over again.

Although enacted more than a decade ago, the FRA remains under-implemented to the extent that a 2017 assessment by the US-based Rights & Resources Initiative showed that just 3% of the minimum potential community forest rights area had been settled through the award of formal titles. Officials have rejected more than 50% of individual and community forest rights (CFR) claims filed by Adivasis and other forest-dwellers. Activists have repeatedly opposed these rejections and even challenged them in court.

“Given that a majority of the land which comes under the Forest Rights Act is yet to be settled, a legislation like CAF poses a serious threat to the pending recognition of people’s rights,” said Tushar Dash, a Bhubaneshwar-based researcher who worked on the RRI study.

The Parsa case demonstrates this. For example, according to the February 2017 ‘no-objection’ letter from the Korea district collector, the over 4,000 acres of land being earmarked for Parsa’s compensatory afforestation project are ‘rajasva van bhumi–chhote baday jhaad ka jungle’, or ‘revenue forest lands, with small and big trees’.

The contradictory nomenclature—i.e., land categorised simultaneously as ‘revenue’ (or under the jurisdiction of the revenue department) as well as ‘forest’ (under the ambit of the forest department)—reflects a deeper mess in the land records of the state revenue and forest departments, as well as outdated land survey settlements. However, the Forest Rights Act applies to all lands categorised as ‘rajasva van bhumi’, officials in Chhattisgarh told IndiaSpend, and communities in possession of such lands and drawing their livelihood from it were entitled to FRA deeds.

Residents of Thaggaon village, Samudribai Salaam, Sonmati Orkera, Sampatiya Salaam and Indukunwar Orkera (left to right), return home after gathering forest produce from the village’s forested commons. While Thaggaon is yet to get recognition under the Forest Rights Act for such community forest rights, officials have earmarked 500 acres of land in the village for compensatory plantations.

In all of the eight villages IndiaSpend visited, villagers decried the poor implementation of the Forest Rights Act, and the daunting process of filing claims. “We submit our claims, but it goes up [to officials] and they just sit on it,” said Singh, the Dhanpur sarpanch. “Most of the claims filed are pending or have got rejected.”

In Gidmudi, the zila panchayat member Neti echoed this, saying, “Most villagers are still not fully aware of their rights, and if they are not accompanied by someone assertive, patwaris and foresters find it easy to brush them away, saying this land belongs to the government, and they cannot get FRA titles.” In Thaggaon village, Rameshwar Das, a member of the village Forest Rights Committee, said, “I help so many Adivasi villagers fill up the forms and provide the required documentation. Their claims get rejected on grounds that some document or the other is missing.”

None of the 16 villages have received community forest rights or titles to the forested commons in their villages.

In contrast to the villagers’ accounts, the official documents earmarking land in the 16 villages for compensatory afforestation say there are no pending FRA claims on the land in question. The document notes that FRA titles had been given on 44 acres in the earmarked land–on average, under three acres in each village. By contrast, more than 4,000 acres have been allotted for compensatory afforestation to facilitate the clearance for the mine.

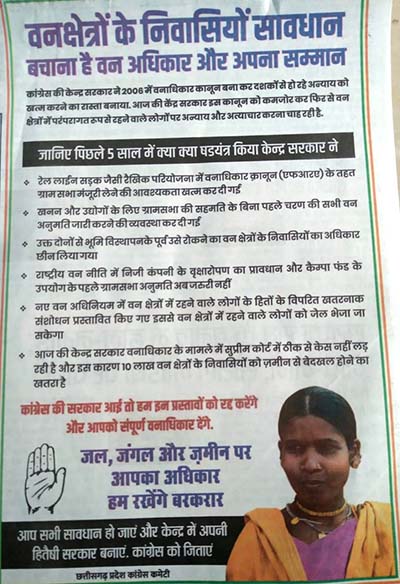

The Congress party was elected to power in Chhattisgarh in December 2018 with a key campaign promise of implementing the Forest Rights Act. This is likely to intensify the CAF-FRA land contests. In the wake of a controversial February 2018 order of the Supreme Court to evict forest dwellers, which is currently on hold, Congress president Rahul Gandhi asked Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel to ensure the law would be properly implemented. He wrote that rights to land, water and forests were integral to the right to life for millions of Adivasis and other forest-dwellers.

Congress president Rahul Gandhi’s letter in February 2019 to Chhattisgarh Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel seeking implementation of the FRA.

Days ago, Baghel tweeted that he had asked forest officials to ensure that Adivasis and forest-dwellers receive their rights to forestlands under FRA. “Such communities can better protect forests, not forest departments,” Baghel wrote, adding, “The Forest Rights Act has not been implemented properly in the last 13 years. We will do it.”

In recent months, the Chhattisgarh government has embarked on a state-wide review of the FRA’s implementation. In Korea district, for example, official figures show that as many as 11,691 or 44% of the forest rights claims have been rejected. Where titles have been given, they have been for a miniscule area–the average size of the holding being 1.1 acres.

When IndiaSpend met Korea’s then district collector Vilas Sandeepan Bhoskar in end-April 2019, he said land for compensatory afforestation for the Parsa mine had been allotted in 2017, well before he had taken charge as collector. He confirmed, however, that the forest department had written to him a few days back asking for a transfer of the land. He asked us to check back with him after he had studied the case.

The high rate of FRA claims rejection was worrying, Bhoskar said, adding that the administration was reviewing all rejected claims and helping vulnerable communities file claims to ensure that no one was deprived of their rights. “Often claims get rejected on technical grounds, or the absence of some document or proof, or because people are not aware,” he said. “But Adivasis and forest-dwellers have been on these lands since ages. We know that. The forest department knows that. Such people are entitled to getting FRA pattas (titles).”

A Congress party advertisement during the recent elections promised forest rights for Adivasi and forest-dweller communities.

When IndiaSpend spoke to him a few days later, Bhoskar said he had written to the state revenue department on May 9, 2019, to seek guidance as he had “limited power as a collector to transfer the land” earmarked for plantations to the forest department. “This is a very large area of land… more than 4,000 acres. If this goes to the forest department, as per the conditions in the forest clearance, its status is to change to ‘Reserve Forest’ or ‘Protected Forest’,” said Bhoskar. He was referring to the standard conditions in forest clearance (permit) documents that the ownership and control of lands earmarked for compensatory afforestation projects must be transferred to the forest department, and their status changed to ‘reserve forests’ or ‘protected forests’.

“Village boundaries, the gram panchayat area… all that will change. FRA claims might also be pending on it since we are reviewing all rejected claims. Keeping all these things in mind, I have written for guidance,” Bhoskar said.

In early June, after just four months in the post, Bhoskar was transferred out of the district.

A conflict foretold

The land tussles playing out in cases such as Parsa were foreshadowed through 2015-18, in public and parliamentary debates before the CAF bill was approved into law in July 2016, as well as during the subsequent drafting of the rules by which the legislation will be implemented.

Adivasi groups expressed fears to Prime Minister Narendra Modi about the impact of the draft law. Voices within the government raised these issues, too.

For example, documents accessed by IndiaSpend under the Right to Information Act show that the environment ministry received repeated letters from the ministry of tribal affairs asking it to ensure that the new CAF law should not undermine the Forest Rights Act, and that it should provide a just deal to forest-dwelling communities.

In March 2015, in comments sent to the environment ministry on its draft CAF bill, the tribal affairs ministry had pointed out that the bill made no mention of the Forest Rights Act and gram sabha consent for afforestation and utilisation of funds, and showed no commitment to spending CAF funds to compensate those affected by forest diversions. These funds, the tribal affairs ministry said, should be shared with the affected gram sabhas. And at least 50% of the net present value (the monetary value of the forest destroyed as determined by the forest department) component of CAF funds should be spent on Adivasi and forest-dwelling communities. A big problem, the tribal affairs ministry added, was “the non availability of land” to carry out compensatory afforestation on.

However, the bill was passed without taking any of the above concerns into account. In parliament, the then environment minister Anil Dave brushed off criticism that the act posed a threat to Adivasi and rural communities’ rights. He instead assured the house that “the CAF rules would provide for adequate consultation with the gram sabha”.

Subsequently, in November 2017, the environment ministry passed the order asking state governments to set up land banks for housing compensatory afforestation projects so that forest clearances could be issued speedily. The tribal affairs ministry again protested the damage this would do to tribal communities, since the categories of land that the environment ministry said be included in the land banks were actually eligible to be settled in favour of communities under the FRA.

Writing to the environment ministry (read the letter here: pdf), it had said the order had been issued “without any consultation with MoTA [the tribal affairs ministry]” and that it “contravened various provisions of the Forest Rights Act.” In particular, the letter said, “the role of the gram sabha has not been given any consideration.”

The tribal affairs ministry asked for the order to be modified to say that land banks should be created only with the informed consent of gram sabhas. It also called for a joint meeting of senior officers of the two ministries “to ensure that the rights of tribals are not affected”.

In the meeting, officials of the tribal affairs ministry reminded their environment ministry colleagues of Dave’s assurance in parliament, the minutes show. The minutes further said, “Officers of the MoEFCC [environment ministry] assured that the commitment still stands. Provision will be made in the CAF rules, which is under preparation, to incorporate the above concern.” (See meeting minutes here: pdf)

However, when the CAF Act’s draft rules were issued by the environment ministry in February 2018, they lacked provisions that would make them compliant with the Forest Rights Act, such as taking the informed consent of gram sabhas in planning and executing afforestation projects, and not undertaking such projects by usurping the individual and community land rights provided for under FRA.

“[T]he CAF rules if operationalised in their current form will lead to harassment, atrocities and crimes against tribals and forest dwellers, and hence to litigation, protests and conflict in forest areas,” Shankar Gopalkrishnan, from the Campaign for Survival and Dignity, an umbrella network of grassroots groups working with forest-dwelling communities across India, wrote to the tribal affairs ministry.

Seconding concerns from Gopalkrishnan and others, the tribal affairs ministry asked the environment ministry in March 2018 to make several changes in the draft rules to ensure gram sabha approval for CA projects, and compliance with the Forest Rights Act. However, the rules eventually passed in August 2018, omitted these substantive revisions.

Adivasi rights groups vigorously critiqued the government’s move. In a letter to the then environment minister Harsh Vardhan, former environment minister Jairam Ramesh dubbed the rules “a blatant breach of assurances given by Dave to ensure compliance with the Forest Rights Act and the authority of the Gram Sabhas”. The minister Vardhan however replied that the rules addressed all such concerns (see the correspondence between the two former ministers: pdf). As our reporting shows, this is not the case.

Baiga tribeswomen in Phulwaripara village in Chhattisgarh’s Bilaspur district protested against plantations in their village in October 2018. They spent 17 days in prison after the local forest department booked them, and are currently out on bail.

In mid-May, IndiaSpend met with Deepak Kumar Sinha, a senior environment ministry official and joint chief executive officer of the national CAF Authority to ask him about the upcoming implementation of the act, and the conflicts it could spark. Sinha pushed back on the view that the CAF Act violated tribal rights or facilitated land grab.

He said the rules issued last August “had taken on board all stakeholders.” He pointed to the fact that the rules now provide for forest departments to consult with gram sabhas while including CA projects in their annual working plans – an annual document devised during colonial times, by which forest departments plan their activities for the year.

But as the Parsa case shows, this provision fails to safeguards tribals’ rights–CA schemes get finalised as part of forest clearances without consultation with the affected villagers. “What is required in the CAF Act is a clear provision of going to the gram sabha for its deliberation and consent when a CA proposal is first floated, not after it has been finalised, for some supposed consultation,” Sarin said.

“Officials have been routinely seizing the land of Adivasis for mining and other projects in this region without their informed consent as required by FRA,” a land rights activist, working with Adivasi communities for the past two decades in north Odisha’s mineral-rich Keonjhar district told IndiaSpend, requesting not to be named. “It is a fool’s dream to imagine that the same officials will sit down with villagers in gram sabas, and democratically discuss plantation projects. The colonial attitude that forestlands are the property of the forest department and the sarkaar still thrives.”

However, Sinha argued, finding land for compensatory afforestation is a part of the clearance process, while the CAF Act is primarily a mechanism for what follows–afforestation. “The forest clearance proposal comes to us from the state… [the ministry] has to trust what state governments say when they identify a certain area as suitable for compensatory afforestation,” he told IndiaSpend. Sinha added, “At the end of the day, states have to decide how much land they want under forest cover. If they do not have the land for afforestation, then they should not propose forest clearance projects.”

Yet state government documents for specific CA schemes indicate that authorities often allocate land for plantations even when fully aware that local communities have historically used these lands for their survival.

“We are mountain people…”

Adivasi residents in Benedihi village of Keonjhar, Odisha have been in conflict with the forest department over plantations on their shifting cultivation lands. Odisha is set to receive the largest share of CAF money in the country.

One example of such an allocation is a compensatory afforestation proposal drafted by the Odisha forest department to offset the forest clearance given to the Odisha Mining Corporation’s Daitari Mine in Keonjhar. The proposal notes that the 1,700 acres of land earmarked for compensatory plantations is being used for podu (shifting) cultivation by local tribes, and for grazing livestock. It states that these lands, which it will take over for plantations, will be enclosed with “strong barbed-wire fencing to protect the area from grazing and other biotic interferences.”

The threat of forcible land-use change and disenfranchisement of tribals is particularly acute in Odisha, which is set to receive the largest chunk of compensatory afforestation funds–at more than Rs 6,000 crore ($862 million), it amounts to more than 10% of the national fund, and more than 10 times the forest department’s annual budget. This suggests the extent of the areas over which the government has permitted forests to be stripped.

The greatest number of clearances have been issued in Keonjhar district, a mountainous landscape of dense forests, vast iron-ore deposits, and more than 50 different indigenous communities who depend on local ecosystems for their survival, yet continue to lack formal titles to these ancestral lands.

For example, lands historically under shifting cultivation by Adivasi communities were declared en masse as government lands, a 2005 study by the development planner Madhu Sarin shows. “44% of Orissa’s supposed ‘forest land’ is actually shifting cultivation land used by tribal communities, whose ancestral rights have simply not been recognised,” Sarin’s report said.

Such lands are now being put into land banks, and allotted from there for compensatory afforestation.

Benedihi, a village of the Bhuiyan tribespeople ensconced in the forested Eastern Ghats of Keonjhar, shows how locals are bearing the brunt of policies taking place in the name of compensatory afforestation.Over 330 acres in the village were included in the district land bank by the state government, and then earmarked in May 2016 to hand over to the forest department as part of a 1,700-acre compensatory afforestation scheme against forestland awarded to Tata Steel Ltd for an iron-ore mine.

A map drawn up by the government marks three plots in Benedihi where the plantations will take place. On the ground, these lands are part of a complex forest ecosystem, and the village is using these lands for a diverse food basket of millets, pulses, greens, tubers and roots through methods of shifting cultivation, and gathering of forest foods. The government has still not settled the CFR claims filed by the village in September 2015.

An undulating forested patch in Benedihi village has been marked out for compensatory afforestation by the forest department to offset forest clearance awarded to a Tata Steel Limited mine.

“Forest officials drive up in their jeeps, walk around with their compasses, put these boards in English, and drive away,” said Tulai Danaika, showing us a compensatory afforestation board erected in an undulating forested patch. “They never tell us anything, or ask us what we think. This has happened thrice now.”

The village practises shifting cultivation by communally drawing up the cyclical scheme by which certain lands would remain fallow, and others would be cultivated. “When the forest department comes and unilaterally fences off land in the village for plantations, our scheme gets disrupted,” Lakhman Pradhan, a former sarpanch said.

Villagers show some of the forest produce and the indigenous crops they harvest through shifting cultivation.

“We are mountain people. These are our desi crops grown through podu. These are our forests. These are the resources we live on. If they take it for plantations, we will face hunger,” Hali Dehury, a woman resident, said. Over a half-an-hour walk, a group of women from the village pointed out multiple medicinal plants on the land, and listed the range of crops the village grows through the year.

“Look at our rich forest floor,” said a loquacious Danaika. “Where the forest department makes plantations, you will not see this. Because they plant acacia and sagwan to harvest for its timber, which will go to the towns and cities. But such species are useless to us–they neither give any fruit, nor do birds live in them, nor do monkeys eat them. Our livestock cannot graze around it, even mushrooms do not grow under it!”

Women residents of Benedihi narrate the damaging effects of plantations on their agriculture and forest food systems.

“The experience of Keonjhar and [the adjoining] Sundergarh districts is that vast areas of forest land, which have been used for shifting cultivation by marginal communities like the Juangs and the Bhuiyans since generations, and are their way of life, are getting fenced off by the forest department in the name of plantations,” the Keonjhar land rights activist said. Such land grabs are unfolding in multiple Adivasi districts of Odisha including Kandhamal, Rayagada and Kalahandi, with cases of villagers even moving the National Human Rights Commission, Odisha-based forest rights researcher Sanghamitra Dubey told IndiaSpend.

Dash pointed out that the CAF-FRA land conflicts unfolding in Korea, Keonjhar and countless other sites across India need urgent redressal. Earmarking land for compensatory afforestation was akin to forest diversion in that it pushed a change in land use, he argued. “The established legal principle in forest diversions is that it requires the informed consent of the gram sabha, and the prior settlement of all forest rights,” said Dash. “We argued that the CAF Act follow the same legal standards for plantations as forest diversions, but the government completely disregarded this.”

When IndiaSpend drew Sinha’s attention to such conflicts, he said the CAF Act was not cast in stone and could always be reviewed in light of the experience of implementation. He was echoing an assertion by the former minister Dave, who had said during the passage of the Act in 2016, “I assure the House that in case the rules are not found adequate in addressing the issues (of adversely impacting tribal communities), we will revisit them after a lapse of a year or so.”

Meanwhile, the CAF Act is set to get off the ground with thousands of crores of rupees flowing to state forest departments, and more and more lands earmarked for plantations, as the government pushes through a near-universal forest clearance rate.

“The demand for, and clashes over, land will only get more acute, to the detriment of tribals,” Dungdung forecasted.

Ramesh Sharma, national coordinator with the land rights group Ekta Parishad, seconded him. “The two laws are genetically different,” said Sharma. “The CAF [Act] is bureaucracy-centric and the Forest Rights Act is people-centric. It is a recipe for conflict.”

(Choudhury is an independent journalist and researcher, working on issues of indigenous and rural communities, forests and the environment. Email: suarukh@gmail.com)

This story was produced with support from the Pulitzer Centre and also appears here.

First published on India Spend