Image Courtesy: Quora.com

The issues arising from the decision of India’s Sufi Muslims to provide a platform to the ‘Hindu Nationalist’ Prime Minister Narendra Modi at the World Sufi Forum in Delhi in mid-March has earlier been addressed by SabrangIndia. But that apart there is another dimension to the Sufi angst which has to do with the petro-dollar funded, aggressive promotion in India, as elsewhere in the world, of a version of Islam which is extremely rigid, highly intolerant and hostile not only to other religions but even other sects within Islam. The All India Ulema Mashaikh Board is the response of Sufi-minded Sunni Muslims at this ongoing attempt to monopolise Muslim space in India.

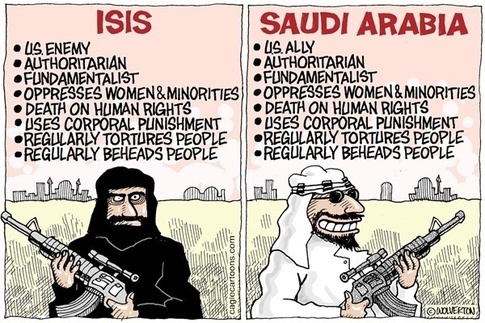

Exporting fundamentalist Islam (Wahhabism) to Muslims across the world emerged, particularly from the 1970s onwards, has been a major preoccupation of the Saudi regime in order to gain legitimacy for the Saudi Arabian monarchy. In India this has meant the growing clout of puritanical and rigid sects like the Ahl-e Hadith and the Deobandis. This is bad news for all those concerned with bridging the growing Hindu-Muslim divide.

Reproduced below are excerpts from a paper by written by Yoginder Sikand in 2005. If anything, its contents are even more relevant today.

Its claim of representing Islamic ‘orthodoxy’ is the Saudi regime’s principal tool in seeking ideological legitimacy. Saudi Arabia prides itself on being, as it calls itself, the only ‘truly’ Islamic State in the world, although this claim is stiffly disputed by many Muslims. Official Saudi Islam, or what is commonly referred to as ‘Wahhabism’ by its opponents, is the outcome of the movement led by the 18th century puritan Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab (1703-91), who, along with Muhammad ibn Saud, was the chief architect of the Saudi State.

Exporting Wahhabi Islam to Muslims elsewhere in the world emerged, particularly from the 1970s onwards, as a major preoccupation of the Saudi regime. This was seen as a vital resource in order to gain legitimacy for the Saudi Arabian monarchy. Transnational linkages are thus crucial in the project of contemporary global Wahhabism. Since Wahhabism is seen by its proponents as the single, ‘authentic’ and ‘normative’ form of Islam, it has an inherent tendency of expansionism, seeking to impose itself on or replace other ways of understanding and practising Islam.

As home to a Muslim population of over 150 million, India has been an important target of Saudi Wahhabi propaganda. Private as well as semi-official Saudi Arabian assistance has made its way to numerous Indian Muslim individuals and organisations.

.jpg)

Photo Courtesy: Clarion Project

The sort of Islam that the Saudis began aggressively promoting abroad, including in India, in the aftermath of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, had a number of characteristic features. It was extremely literalist; it was rigidly and narrowly defined, being concerned particularly with issues of ‘correct’ ritual and belief, rather than with wider social and political issues; it was viciously sectarian, branding dissenting groups, such as Shias and followers of the Sufis as ‘enemies’ of Islam; and, finally, it was explicitly and fiercely critical of ideologies and groups, Muslim as well as other, that were regarded as political threats to the Saudi regime. Accordingly, these were routinely castigated as ploys of the ‘enemies of Islam’.

Intra-Sunni rivalry and the emergence of the Ahl-e Hadith

The establishment of British rule in India had momentous consequences for notions of Muslim and Islamic identity. The widely shared perception of Islam being under threat helped promote a feeling of Muslim unity transcending sectarian and ethnic boundaries. Yet, at the same time, British rule opened up new spaces for intra-Muslim rivalry. It was in this period that serious differences emerged within the broader Sunni Muslim fold, leading to the development of neatly-defined and on numerous issues mutually opposed sect-like groups, the principal being the Deobandis, the Barelvis and the Ahl-e Hadith. Each of these groups claimed a monopoly of representing the ‘authentic’ Sunni tradition, or the Ahl al-Sunnah wal Jamaah, branding rival claimants as aberrant and, in some cases, even as apostates. This brought to the fore the deeply fractured and fiercely contested nature of Sunni ‘orthodoxy’.

The pioneers of the Ahl-e Hadith saw themselves as struggling to promote what they believed to be the ‘true’ Islam of Muhammad and his companions. Like most other Sunni ulema, they considered the Shias to be outside the pale of Islam and therefore, kafirs. In addition, they believed that the other Sunni groups too had strayed from the path of the ‘pious predecessors’ (salaf).

Overall, they saw their mission as rescuing Muslims from what they saw as the sin of shirk and guiding them to the ‘pure monotheism’ (khalis tauhid) of the Prophet and his companions. Most of them were inspired by the example of Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab and his companions, particularly appreciating the Wahhabis’ criticism of popular custom. Yet, they did not identify themselves as such, refusing the label of Wahhabi that their detractors used to dismiss them.

Many Hanafi ulema saw the Ahl-e Hadith as a hidden front of the Wahhabis, whom they regarded as ‘enemies’ of Islam for their fierce opposition to the adoration of the Prophet and the saints, their opposition to popular custom and to taqlid, rigid conformity to one or the other of the four generally accepted schools of Sunni jurisprudence.

Further, they also saw the Ahl-e Hadith as directly challenging their own claims of representing normative Islam. Numerous Hanafi ulema issued fatwas branding the Ahl-e Hadith as virtual heretics, contemptuously referring to them as ghair muqallids for their opposition to taqlid, which they believed to be integral to established Sunni tradition. Hanafi opposition to the Ahl-e Hadith was fierce. In many places Hanafis refused them admittance to their mosques, schools and graveyards. Marital ties with them were forbidden, and in some places followers of the Ahl-e Hadith even faced physical assault.

In recent years Ahl-e Hadith scholars have penned scores of books and tracts sternly denouncing customs that many Indian Muslims share with their Hindu neighbours, a legacy of their pre-Islamic past. These also include customs, such as those associated with popular Sufism and the cults of the saints, which enabled Islam to take root in India and to adjust to the Indian cultural context. As Ahl-e Hadith writers see it, these are all ‘wrongful innovations’, having no sanction in the Prophet’s sunnah, and hence must be rooted out.

The Saudi-Ahl-e Hadith connection: Wahhabism as an external policy tool

The 1970s witnessed a growing involvement of certain Arab states, institutions and private donors in sponsoring a number of Islamic organisations and institutions in India. This was a direct outcome of the boom in oil revenues, particularly following the hike in oil prices by OPEC members in the wake of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war.

Although the precise magnitude of Arab assistance to Indian Muslim organisations cannot be ascertained, it was certainly significant, although the Indian press routinely exaggerated it, leading to a scare of petrodollars flooding the country as part of an alleged grand conspiracy to convert poor, particularly ‘low’ caste, Hindus to Islam.

In actual fact, few Muslim organisations actually engaged in missionary work among Hindus received such money. Instead, most Arab, including Saudi, financial assistance went to Muslim organisations to establish mosques, madrassas and publishing houses. To a lesser extent, money was channelled to Muslim organisations to set up schools and hospitals in Muslim localities and to provide scholarships to needy Muslim students.

Saudi funds for Muslim institutions in India have come through a range of sources, including the Saudi State, various Saudi-sponsored Islamic organisations such as the Mecca-based Rabita al-Alami al-Islami (World Muslim League) and the Dar ul-Ifta wal Dawat ul-Irshad, as well as private donors, mostly rich sheikhs, some with close links to the Saudi ruling family. Several Indian Muslims working in Saudi Arabia in various capacities also send back money to fund Islamic institutions, based mainly in towns and villages where their families live.

Monetary assistance to selected Islamic institutions is only one method through which the Saudis have sought to patronise and influence key Muslim leaders and opinion makers in India. Other forms of assistance include sponsored Haj pilgrimages for Muslim leaders, including ulema, patronising of selected publishing houses, scholarships for madrassa students to study in Saudi Islamic universities and jobs for such graduates in both the private as well as public sector within Saudi Arabia.

The largest beneficiary of this largesse is believed to be the Ahl-e Hadith, although the Jamaat-i Islami and the Deobandis are also said to have benefited to some extent. The Barelvis and the Shias, both of whom regard Wahhabism as wholly heretical, have received little or no financial support at all from Saudi sources. This itself suggests that Saudi finance to Muslim institutions in India is intended to serve and promote a particular ideological vision of Islam, one that ties in with the interests of the Saudi regime and its official Wahhabi ulema.

Saudi Arabia emerged as a significant sponsor of Islamic institutions internationally, including in India, only in the 1970s. This was a period of intense ideological struggle in the Arab world. Arab socialism and pan-Arab nationalism under Nasser in Egypt and the Baathists in Syria and Iraq and various communist parties active in numerous Arab states all called for the overthrow of monarchical regimes in the region, which they saw as lackeys of the United States and as helping the Zionist occupation of Palestine. Within Saudi Arabia itself voices of dissent and protest emerged, including from those who had been influenced by socialist trends elsewhere in the region.

The literature produced by several Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India helps promote a version and vision of Islam that is almost identical to that of the Wahabbis of Saudi Arabia, and hence one that fits in with the interests of both the Saudi Wahhabi ulema as well as the Saudi State. The claim of the Saudi monarchy as representing the sole ‘authentic’ Islamic regime in the world is repeatedly stressed in several Ahl-e Hadith writings, and reflects the close links, ideological as well as financial, between several Indian Ahl-e Hadith leaders and the Saudi State and its official Wahhabi ulema.

Then came the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, which led to fears of an export of revolutionary, anti-monarchical Islam to the Arab world, including to Saudi Arabia. Ayatollah Khomeini vehemently denounced the Saudi kingdom, insisting that Islam had no place for monarchical rule. He also bitterly attacked the Saudis for being American stooges and for willingly acquiescing in American support for Israel.

In his will, made public in 1989, he denounced the Saudi regime as ‘anti-Islamic’, claiming that it was in league with ‘Satanic powers’. He argued that Wahhabism represented ‘anti-Koranic ideas’ and a ‘baseless, superstitious cult’, and was aimed at destroying Islam from within. Radical appeals emanating from Tehran, including anti-Wahhabi and anti-Saudi sentiments soon captured the imagination of Muslims all over the world.

The Iranian Revolution played the role of a major catalyst in moulding Saudi foreign policy, in which the export of its official Wahhabi form of Islam emerged as a key instrument. The anti-monarchical thrust of the revolution was seen by the Saudi regime as a menacing threat. If the Shah of Iran, America’s closest and strongest ally in the region, could be overthrown as a result of the passionate appeals of a charismatic Imam, the Saudi rulers, it was painfully realised, could well meet the same fate. Consequently, the Saudis, backed by the Americans, began investing heavily in promoting Wahhabi Islam abroad in order to counter the appeal of the Iranian Revolution, both within Saudi Arabia itself and abroad.

Stressing the regime’s ‘Islamic’ credentials now came to be relied upon as the principal tool to strengthen it and to stave off challenges from internal as well as external opponents, from Muslims opposed to the regime’s corrupt and dictatorial ways and its close alliance with the imperialist powers, principally the United States. Saudi export of Wahhabism was given a further boost with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, when the Saudis, supported by the Americans, pumped in millions of dollars to fund Wahhabi-style schools and organisations in Pakistan in order to train guerrillas to fight the Russians. While such assistance, in Afghanistan and elsewhere, was presented as a sign of Saudi Arabia’s professed commitment to ‘true’ Islam, it also functioned as a thinly veiled guise for promoting the interests of the Saudi regime. In exporting this brand of Islam abroad, India, home to the second largest Muslim community in the world, received particular importance.

The sort of Islam that the Saudis began aggressively promoting abroad, including in India, in the aftermath of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, had a number of characteristic features. It was extremely literalist; it was rigidly and narrowly defined, being concerned particularly with issues of ‘correct’ ritual and belief, rather than with wider social and political issues; it was viciously sectarian, branding dissenting groups, such as Shias and followers of the Sufis as ‘enemies’ of Islam; and, finally, it was explicitly and fiercely critical of ideologies and groups, Muslim as well as other, that were regarded as political threats to the Saudi regime. Accordingly, these were routinely castigated as ploys of the ‘enemies of Islam’.

Saudi patronage and the Indian Ahl-e Hadith

A hugely disproportionate amount of Saudi aid to Indian Muslim groups in the decades after the Iranian Revolution is said to have gone to institutions run by the Ahl-e Hadith. This is hardly surprising, given the shared ideological tradition and vision of the Ahl-e Hadith and the Saudi Wahabbis. One result of the generous Saudi patronage of the Indian Ahl-e Hadith has been that there has been a growing convergence between the latter and the Saudi Wahhabi ulema, so much so that today there is hardly any difference between the two groups.

Saudi finance to Indian Ahl-e Hadith institutions has heavily influenced the contents of the vast amount of literature that they produce and distribute. In the last two decades there has been a mushroom growth in the number of Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India. Several of them are said to receive Saudi funds, directly or otherwise. Many of them produce low-priced books, and, now, audio tapes, video cassettes and compact discs, and some even operate their own web sites. Most of the authors whose works they publish are Indian and, to a lesser extent, Pakistani Ahl-e Hadith ulema who have received higher education in various Saudi universities.

Several of them are currently working in various official as well as private Islamic organisations in Saudi Arabia itself. Their vision and understanding of Islam is indelibly shaped by their own experiences in Saudi Arabia. They see the Saudi Wahhabi version of Islam as normative and other forms of Islam as deviant.

Much of the literature produced by Indian Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses focusses on the minutiae of ritual practices and beliefs. This is a reflection, in part, of the overwhelmingly literalist understanding of Saudi Wahhabi Islam. Scores of books penned by Ahl-e Hadith ulema are devoted to intricate discussion of what they regard as the ‘correct’ methods of praying, performing ablutions and offering supplications, as well as rules and regulations related to food, dress, marriage, divorce and so on.

A principle purpose of these publications is to attack rival Muslim, including Sunni, groups, and to sternly condemn them as ‘aberrant’ on account of differences in their methods of performing rituals and their rules governing a range of issues related to normative personal and collective behaviour.

Another interesting feature of the literature produced by Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India, and one that is directly linked to the close association between the Ahl-e Hadith and the Saudi Wahabbis, is a fierce hostility to local beliefs and practices. This hostility, while having been a defining feature of the early Ahl-e Hadith, has been further exacerbated with the growing Saudi-Ahl-e Hadith nexus. In recent years Ahl-e Hadith scholars have penned scores of books and tracts sternly denouncing customs that many Indian Muslims share with their Hindu neighbours, a legacy of their pre-Islamic past.

These also include customs, such as those associated with popular Sufism and the cults of the saints, which enabled Islam to take root in India and to adjust to the Indian cultural context. As Ahl-e Hadith writers see it, these are all ‘wrongful innovations’, having no sanction in the Prophet’s sunnah, and hence must be rooted out. In their place they advocate an adoption of a range of Arab cultural norms and practices which are seen as genuinely ‘Islamic’.

The publication of Urdu translations of the compendia of fatwas of leading Saudi Wahhabi ulema by Indian Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses is a reflection of this cultural alternative that they seek to provide to take the place of what they see as ‘un-Islamic’ practices widely prevalent among many Indian Muslims. This has added to the conflict with other Muslim groups, most particularly with the Barelvis, who are associated with the cults of the Sufis. The ‘Saudi Arabisation’ of Islam and Indian Muslim culture that the Ahl-e Hadith seeks to promote also inevitably further widens the cultural chasm between Muslims and Hindus.

As many Ahl-e Hadith ulema see it, and this is reflected in their writings as well, Hinduism is hardly different from the pagan religion of the Arabs of the pre-Islamic Jahiliya period. Although most of them do not advocate conflict with Hindus, some Ahl-e Hadith scholars insist on the need for Muslims to have as little to do with the Hindus as possible, for fear of the ‘deleterious’ consequences this might have for the Muslims’ own commitment to and practice of Islam.

Like other Muslim groups, Indian Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses have also paid particular attention to combating their Muslim rivals. This cannot be understood without taking into account the Saudi connection. Scores of books have been penned by Indian Ahl-e Hadith ulema, branding Sufis, Shias and Deobandis as heretical.

Tirelessly claiming in their writings to being the sole representatives of ‘normative’ Islam and, in the process, identifying themselves with the Saudi Wahhabi ulema, enables the Indian Ahl-e Hadith ulema to present themselves as faithful allies of the Saudis, which in turn helps earn them recognition as well as monetary assistance from Saudi sponsors. In addition, such publications also serve the purpose of presenting the Saudi Wahhabi version of Islam as normative, and in putting forward the claim of the Saudi regime to being the only one in the world sincerely and seriously committed to ‘genuine’ Islam.

The Iranian Revolution played the role of a major catalyst in moulding Saudi foreign policy, in which the export of its official Wahhabi form of Islam emerged as a key instrument. The anti-monarchical thrust of the revolution was seen by the Saudi regime as a menacing threat.

Access to Saudi funds has therefore led to heightened conflict between various Muslim sectarian groups in India, as Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses produce and distribute literature on a large scale bitterly attacking their rivals of being Muslim only in name.

Heightened intra-Muslim polemics within India are not unrelated to the interests of the Saudi regime. Thus, the virulently anti-Shia and anti-Sufi propaganda material churned out by various Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India, some of this said to be sponsored by Saudi patrons, serves the purpose of denouncing as outside the pale of Islam Muslim groups who are opposed to Wahhabism and the Saudi State, these often being branded as ‘enemies’ of Islam. In this way the literature produced by several Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India helps promote a version and vision of Islam that is almost identical to that of the Wahabbis of Saudi Arabia, and hence one that fits in with the interests of both the Saudi Wahhabi ulema as well as the Saudi State.

The claim of the Saudi monarchy as representing the sole ‘authentic’ Islamic regime in the world is repeatedly stressed in several Ahl-e Hadith writings, and reflects the close links, ideological as well as financial, between several Indian Ahl-e Hadith leaders and the Saudi State and its official Wahhabi ulema.

Numerous books penned by Indian Ahl-e Hadith scholars discuss in detail the ‘great’ contributions of the present rulers of Saudi Arabia to the ‘Islamic cause’, inevitably concluding with the claim that Saudi Arabia under its present masters represents the only ‘truly’ Islamic State in the world today. They also make it a point to call on God to bless the Saudi king and pray for his continued rule. The Saudi monarch is invariably presented as a pious, fully committed Muslim, whose sole concern is, so it is sought to be argued, the protection and promotion of ‘authentic’ Islam. Support for this ‘authentic’ Islam and for the Saudi rulers are presented as indivisible.

Interestingly, there is no reference at all in Ahl-e Hadith writings to the widespread dissatisfaction within Saudi Arabia itself with the ruling family. Nor is there any reference to the rampant corruption in the country, the lavish lifestyles of the princes, and to Saudi Arabia’s close links with the United States.

Nor, still, is there ever any mention of the claim, put forward by many Muslims, that monarchy is ‘un-Islamic’, particularly one like the despotic and corrupt Saudi regime. This is added evidence of the fact that Saudi-sponsored propaganda abroad is tailor-made to suit the interests of its ruling family.

Ahl-e Hadith-Deobandi polemics and the Saudi nexus

As a claimant to Sunni ‘orthodoxy’, the Ahl-e Hadith is not alone in denouncing the Shias as heretics and therefore outside the pale of Islam. In fact, many Deobandi and Barelvi ulema share the same opinion. Hence the virulent opposition to the Shias on the part of the Ahl-e Hadith is hardly surprising. Given its commitment to what it sees as ‘pure’ monotheism and its fierce opposition to ‘wrongful innovations’, its denunciation of the Barelvis, who are associated with the cults of the Sufis, is also understandable.

What seems particularly intriguing, however, is the fact that, of late, Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India have been devoting particular attention to denouncing the Deobandis who, while being muqallids as well as proponents of a reformed Sufism, share with the Ahl-e Hadith a commitment to strict compliance with the Shariah and the extirpation of what they describe as bidaah. In that sense, the Ahl-e Hadith are closer in doctrinal terms to the Deobandis than to any other Indian Sunni group. Despite this, it appears that in recent years Indian Ahl-e Hadith scholars have been focussing considerably more attention on combating the Deobandis than critiquing their Barelvi and Shia rivals. This seemingly puzzling development begs an explanation.

One possible reason for this is that the Deobandis in India are far more organised and influential than the Barelvis. The Deobandis manage a number of influential organisations, madrassas and publishing houses all over India. Consequently, they have probably been more effective in critiquing the Ahl-e Hadith than their other rivals, which in turn has forced the Ahl-e Hadith to pay particular attention to the challenge they face from the Deobandi front. In addition to this factor are other developments, related to struggles over money, influence and authority, which have made for a sharp intensification of rivalries between the Ahl-e Hadith and the Deobandis in recent years. The Saudi connection seems to have played a major role in abetting these conflicts.

The Deobandis, by and large, seem to have maintained the somewhat ambiguous attitude of their elders towards the Ahl-e Hadith and the Wahabbis till at least the late 1970s, when the situation began to change with new access to Saudi funding. In the course of the Afghan war against the Soviets, the Saudis recognised that the Deobandis were far more influential and had a far larger presence than the Ahl-e Hadith in both Pakistan as well as Afghanistan. Consequently, much Saudi funding began making its way to Deobandi madrassas in Pakistan in order to train guerrilla fighters armed with a passion for jehad against the Russians. A shared commitment to a Shariah-centric Islam made such assistance acceptable to both parties.

Islam is conveniently marshalled and often interpreted in diametrically opposing ways by the Saudi regime to suit its own strategic and ideological purposes abroad. Saudi Arabia is said to have been the largest financier of radical Islamist groups abroad, some of whom, as in the Philippines, Chechnya, Bosnia and Kashmir, have taken to armed struggle and terrorism against non-Muslim States. Saudi-funded literature routinely extols such groups as mujahids engaged in a legitimate Islamic jehad.

Impact of recent developments on Saudi links with Indian Muslim groups

The 1990s were characterised by fierce polemical battles between the Ahl-e Hadith and the Deobandis in India, with each group charging the other of being ‘anti-Islamic’ and as hidden fronts of the ‘enemies’ of Islam. Although the two groups continue to regard each other as fierce rivals, the sharp polemical exchanges between them now seem to have dampened somewhat. One factor for this is probably the strong need that many Muslims feel to present a united front to combat the challenge of aggressive Hindu groups in the country.

Another important factor for the apparent decline in overt strife between the Ahl-e Hadith and the Deobandis in recent years is what seems to be a significant shift in Saudi strategy. Following the events of September 2001, Saudi Arabia came under tremendous pressure from the United States to clamp down on Wahhabi militants at home and abroad. The Saudi strategy of sponsoring radical Wahhabism seemed to have boomeranged, as a new generation of Islamist radicals emerged within Saudi Arabia itself, critiquing the Saudi regime for its corruption and for its close links with the United States. Consequently, the Saudi Arabians were forced to take action against their own internal radical Islamist opponents, realising the major challenge that they posed to the Saudi monarchy.

Simultaneously, and because of these developments, Saudi aid to Wahhabi groups abroad, including India, is said to have declined somewhat. This will naturally have a major impact on relations between different Muslim groups in India, and will most notably impact on the expansion of the Ahl-e Hadith, who have been the major recipient of Saudi assistance in recent years.

Another possible indication of the shift in Saudi strategy is the fact that of late certain Ahl-e Hadith publishing houses in India have brought out books praising the Saudi State and critiquing what they describe as the ‘terrorists’ who wish to weaken it. These books argue that the ‘correct’ method of the political ‘reform’ that Islamist opponents of the regime seek is not through violence but rather through ‘guiding’ the political authorities to follow the path of God by providing them with ‘Islamic’ advice.

This shows how Islam is conveniently marshalled and often interpreted in diametrically opposing ways by the Saudi regime to suit its own strategic and ideological purposes abroad. Saudi Arabia is said to have been the largest financier of radical Islamist groups abroad, some of whom, as in the Philippines, Chechnya, Bosnia and Kashmir, have taken to armed struggle and terrorism against non-Muslim States. Saudi-funded literature routinely extols such groups as mujahids engaged in a legitimate Islamic jehad. Yet, faced now with its own internal and increasingly vocal Islamist opposition, it considers similar movements within Saudi Arabia as major sources of ‘strife’ and as clearly ‘un-Islamic’. Whether, as a result of increasing international pressure, the Saudis will be willing to extend the same logic to Islamist groups abroad whom they have been patronising for many years is a moot point.

(This article is an excerpt from the writer’s monograph, "Intra-Muslim Rivalries in India and the Saudi Connection" which can be accessed from his web site www.islaminterfaith.org. Archived from Communalism Combat, March 2005, Year 11, No. 106).