Introduction

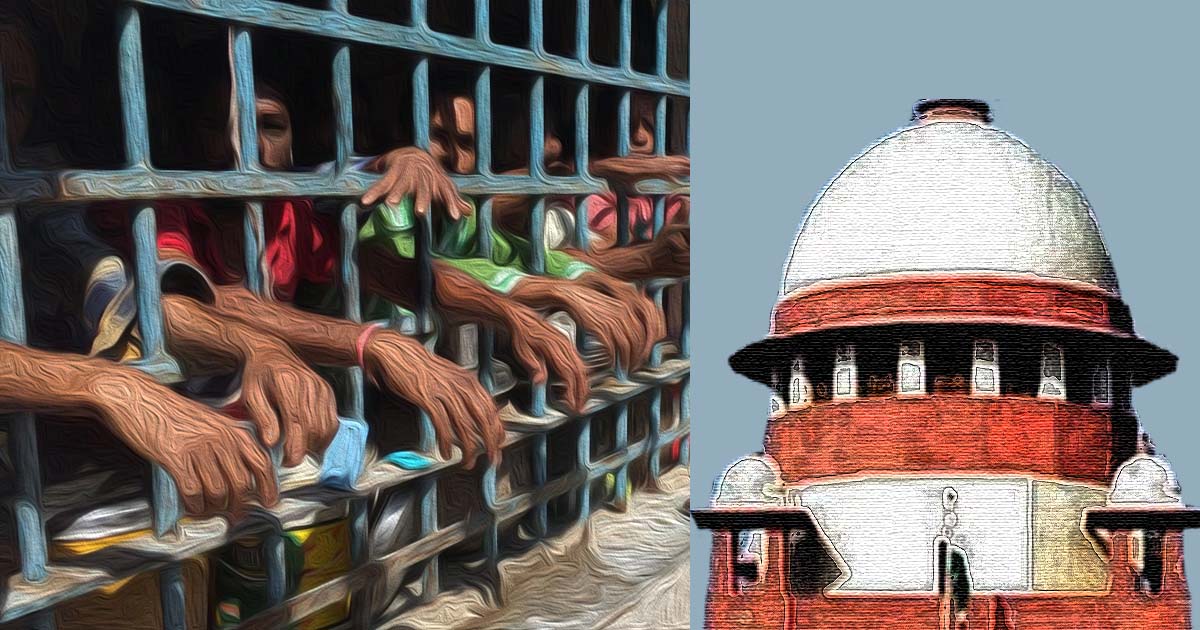

On April 23, while hearing the plea for prison reforms (W.P.(C) No. 406/2013), the Supreme Court bench of Justices Hima Kohli and Ahsanuddin Amanullah castigated the States for not providing proper details in their affidavits about the conditions of prisons, and neglecting the court directives to carry out prison reforms in district and central jails based on the recommendations of District Committees setup by the court through its order on January 30, 2024. It also expressed displeasure over the States’ lackadaisical approach for not treating the matter seriously, and for failing to provide necessary information about the steps taken to improve prison infrastructure and living standards in jails.

The court gave couple of weeks’ time to the Chief Secretaries of the concerned States/UTs to file the affidavits, “emphasizing that the affidavits shall mention the manner in which recommendations given by the respective Committees are proposed to be implemented and the timelines for such implementation”, LiveLaw reported.

Notably, in its January order the bench had directed the States/UTs to create District Committees comprising District Judge, District Magistrate, Superintendent of Police, Secretary of District Legal Services Authority, and Superintendent of Jail, to study the conditions of prisons at a district level and send their recommendations to States for improving living conditions of prisoners, including creation of new prisons to reduce overcrowding, and ensuring proper sanitation, hygiene, food, health, education, and other services in the prisons.

In one of its earlier judgements in the same case, in February 2016, the bench of Justices Madan Lokur and R.K. Agrawal had asked States to strictly implement Model Prison Code 2016, and cautioned that it “needs to be implemented with due seriousness and dispatch” so that it is not “reduced to yet another document that might be reviewed only decades later, if at all”. In the same judgement, the bench had also taken note of the plight of undertrial prisoners and had urged the States to see to it that poor undertrial prisoner who have secured bail do not languish in jails due to their poor economic status or inability to pay bail money. Emphasising on the need to improve prison conditions, the bench directed in its judgement that “The Director General of Police/Inspector General of Police in-charge of prisons should ensure that there is proper and effective utilization of available funds so that the living conditions of the prisoners is commensurate with human dignity. This also includes the issue of their health, hygiene, food, clothing, rehabilitation etc.” The bench then had relied on landmark judgements like Sunil Batra ((1978) 4 SCC 494), Sunil Batra (II) v. Delhi Administration ((1980) 3 SCC 488), Rama Murthy v. State of Karnataka ((1997) 2 SCC 642), and T. K. Gopal v. State of Karnataka ((2000) 6 SCC 168) to argue in favour of humanitarian prison reforms.

Rama Murthy judgement specifically lists down 9 areas of immediate concern, which includes:

- Over-crowding

- Delay in trial

- Torture and ill-treatment

- Neglect of health and hygiene

- Insubstantial food and inadequate clothing

- Prison vices

- Deficiency in communication

- Streamlining of jail visits

- Management of open-air prisons

Background on Prison Reforms

Since the establishment of modern prison in India by TB Macaulay in 1935, there has been numerous attempts by governments, both pre-independence and post-independence, to change the living conditions in prisons. Post-independence, Pakwasa Committee in 1949 suggested that prisoners can be used as labour for road work without any intensive supervision over them. It was from this time onwards that a system of wages for prisoners for their labour was introduced, and subsequently, certain liberal provisions were also introduced in jails manuals by which well-behaved inmates were rewarded with remission in their sentence, as per the report prepared by the Lok Sabha Secretariat on prison reforms.

The Government of India appointed the All-India Jail Manual Committee in 1957 to prepare a model prison manual following the recommendations of Dr. W.C. Reckless regarding prison reform in India, the latter being the United Nations expert on correctional work. The aforementioned committee prepared the Model Prison Manual in 1960, which became the basis for the Central Government to appoint a working group on prisons in 1972, which recommended classification of prisoners and their treatment based on certain principles.

In 1980 the Government of India set-up a Committee on Jail Reforms under the Chairmanship of Justice A. N. Mulla, which submitted its report in 1983 recommending the following measures:

- Improving prison condition by making available proper food, clothing, and sanitation.

- The prison staff to be properly trained and organized into different cadres, with the setting up an All-India Service called the Indian Prisons & Correctional Service.

- After-care, rehabilitation and probation to be an integral part of prison service.

- The press and public to be allowed inside prisons and allied correctional institutions periodically, so that the public may have first-hand information about the conditions of prisons and be willing to co-operate in rehabilitation work.

- Undertrials in jails to be reduced to bare minimum and they be kept away from convicts. Furthermore, the number of undertrials to be reduced by speedy trial and liberalization of bail provisions.

- The Government may make an effort to provide adequate financial resources.

Shortly afterwards in 1987, Justice Krishna Iyer Committee, setup to study the conditions of women prisoners, recommended induction of more women into the police force in view of their special role in tackling women and child offenders.

Following the Supreme Court direction in Rama Murthy (mentioned above) to prepare uniform prison laws across the country, a draft Model Prison Management Bill (The Prison Administration and Treatment of Prisoners Bill, 1998) was circulated among the States, but pertinently, the Bill was never finalised. Since then, two Model Prison Manual(s) have already come out, one in 2003, and the latest one in 2016.

In 2021, Rajya Sabha MP K.C. Ramamurthy requested the Minister of Home Affairs to provide details about the salient features of 2016 Model Prison Manual, its implementation by the States, and how the Government intends to ensure the implementation of Nelson Mandela Rules in prisons.

Responding to his query, Minister of State for Home Affairs (MoS), G. Kisan Reddy, stated the following in response to highlight the salient features of Model Prison Manual 2016:

- It brings in basic uniformity in laws, rules and regulations governing the administration of prisons and the management of prisoners all over the country

- Lays down the framework for both sound custody and treatment of prisoners

- Spells out minimum standards of institutional services for the care, protection, treatment, education, training and re-socialisation of incarcerated offenders

- Evolving procedures for the protection of human rights of prisoners within the limitations imposed by the process of incarceration

- Individualises institutional treatment of prisoners in keeping with their personal characteristics, behavioural patterns and correctional requirements

- Forging constructive linkages between prison programmes and community- based welfare institutions in achieving the objective of the reformation and rehabilitation of prisoners

- Access to free legal services: legal aid clinics, jail visiting advocates, constitution of under-trial review committees

- Provisions for women prisoners including safeguards, protections, special programmes, counselling, focussed after-care and rehabilitation, as well as provisions for children of women prisoners

- Legal aid to prisoners sentenced to death, mental health evaluation, procedures and channels for mercy petition

- Prison Modernisation: Use of technology/software including Personnel Information System, installation of CCTVs etc. to prevent violation of Human Rights

While commenting on the conformity to the Nelson Mandela Rules, MoS for Ministry of Home Affairs suggested that States are ultimately responsible for their implementation, and the Union Government has already sent the respective Rules to the States, asking them to implement the same. The response also noted that the Union has advised the States to have these rules (Nelson Mandela Rules) “translated in local language and disseminate the guidance contained therein to all prison officials to ensure that these rules are followed by the officials concerned in dealing with prison inmates.”

CJP’s endeavour towards bringing police accountability and prison reforms

CJP has in the past reported about the incidents affecting right to liberty of the citizens (Article 21) due to police accesses and has also advocated for the police reforms. In the case of Pankaj Kumar Sharma v Govt of NCT of Delhi & Ors, CJP reported how the Delhi High Court came down heavily on the Delhi Police personnel responsible for illegally detaining the citizen (Pankaj Kumar Sharma) and issued a compensation of 50,000 rupees from the salaries of the two police officials responsible for the misconduct, namely, (Sub-Inspectors) Rajeev Gautam and Shamim Khan. In the judgement delivered by Justice Subramonium Prasad, the court noted that “The time spent in the lock-up by the petitioner, even for a short while, cannot absolve the police officers who have deprived the petitioners of his liberty without following the due procedure established by law… This Court is of the opinion that a meaningful message must be sent to the authorities that police officers cannot be law unto themselves”.

In the aforementioned case, the court relied on number of important judicial precedents, including D K Basu v. State of West Bengal, in which the apex court had released guidelines to be followed by the police while arresting or detaining a concerned citizen.

The DK Basu guidelines among other things require the police to ensure the following:

- The police personnel carrying out the arrest and handling the interrogation of the arrestee should bear accurate, visible and clear identification and name tags with their designations. The particulars of all such police personnel who handle interrogation of the arrestee must be recorded in a register

- That the police officer carrying out the arrest shall prepare a memo of arrest at the time of arrest and such memo shall be attested by at least one witness, who may be either a member of the family of the arrestee or a respectable person of the locality from where the arrest is made. It shall also be counter signed by the arrestee and shall contain the time and date of arrest.

- A person who has been arrested or detained and is being held in custody in a police station or interrogation centre or other lock up, shall be entitled to have one friend or relative or other person known to him or having interest in his welfare being informed, as soon as practicable, that he has been arrested and is being detained at the particular place, unless the attesting witness of the memo of arrest is himself such a friend or a relative of the arrestee.

- The time, place of arrest and venue of custody of an arrestee must be notified by the police where the next friend or relative of the arrestee lives outside the district or town through the Legal Aid Organisation in the District and the police station of the area concerned telegraphically within a period of 8 to 12 hours after the arrest.

- The person arrested must be made aware of his right to have someone informed of his arrest or detention as soon as he is put under arrest or is detained.

- An entry must be made in the diary at the place of detention regarding the arrest of the person which shall also disclose the name of the next friend of the person who has been informed of the arrest and the names land particulars of the police officials in whose custody the arrestee is.

- The arrestee should, where he so requests, be also examined at the time of his arrest and major and minor injuries, if any present on his/her body, must be recorded at that time. The ‘Inspection Memo’ must be signed both by the arrestee and the police officer effecting the arrest and its copy provided to the arrestee.

- The arrestee should be subjected to medical examination by the trained doctor every 48 hours during his detention in custody by a doctor on the panel of approved doctors appointed by Director, Health Services of the concerned State or Union Territory, Director, Health Services should prepare such a panel for all Tehsils and Districts as well.

- Copies of all the documents including the memo of arrest, referred to above, should be sent to the Magistrate for his record.

- The arrestee may be permitted to meet his lawyer during interrogation, though not throughout the interrogation.

In addition, the judgement also relied on Nilabati Behera (1993 AIR 1960) to provide compensation to the victim of illegal act of detention carried out by the police. Importantly, in Nilabati Behera the court had noted that “citizen complaining of the infringement of the indefeasible right under Article 21 of the Constitution cannot be told that for the established violation of the fundamental right to life, he cannot get any relief under the public law by the courts exercising writ jurisdiction.”

Similarly, CJP continued to raise awareness about the Police Complaints Authorities (PCA) in Maharashtra, for which a user guide was initially released by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI). PCAs were established in Maharashtra in 2014 at the state level (1) and divisional level (6) to register complaints or grievances against police personnel for serious misconduct, corruption, or abuse of authority.

PCAs have wide ambit of power to perform the following functions:

- Conduct suo moto inquiries or through complaints against Police Officers, hear all concerned persons, receive evidence, and give recommendations to be implemented by the police department and the state government

- Advise the state government to ensure the protection of witnesses, victims and their families who face, or may face, threats or harassment for filing a complaint against the police

- Visit any police station, lock-up or other place of detention used by the police (with written authorisation from the Chairperson).

- Receive complaints involving death in police custody, grievous hurt under Section 320 of the IPC, rape or attempt to commit rape, arrest or detention without following procedure, corruption, extortion, land or house grabbing and any other serious violation of law or abuse of authority

In 2018, CJP once again raised its voice against the growing misuse of police across the country to supress peaceful protests by the citizens. It moved the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) demanding guidelines on how the police should behave with peaceful protestors in order to protect citizens’ right to peaceful protest under Article 19 of the Constitution.

CJP-PUCL manifesto on prison reforms and police accountability

Before the election to Lok Sabha 2024 took off, CJP and PUCL jointly released their manifesto, which among other things also deal with the long pending issue of prison reforms, especially with regard to the rights of undertrial prisoners. The following demands have been raised in our manifesto:

- Follow and implement relevant judgments of the Supreme Court on under trials and ensure prison reforms in accordance with the Model Manual for Prison Reform, 2016.

- Order the immediate release of under trials who have already served half their maximum sentence.

- Ensure regular monitoring of prison conditions, particularly in relation to women and children through the implementation of district and other monitoring committees as per the Model Manual Prison Reform, 2016.

- Ensure adequate sanitation and health facilities, and emphasise cleanliness and adequate food and clean water; access to work, reading and writing materials in all prisons.

- Ensure efficient, regular and quality legal aid to all under trials and other prisoners.

- Ensure the emoluments to the prison employment staff (including services of convicted prisoners utilised by the state) meet the standards of the updated standards in the Minimum Wages Act, 1948.

- Ensure training and sensitisation of all Jail/Prison staff in national and international human rights standards to ensure just and humane conditions within prisons.

- Explore the shift to an Open Prison System for less stringent crimes.

- Allow human rights defenders (HRDs) full and free access to police stations, prisoners, etc.

- Abolition of capital punishment and all forms of torture.

- Ratification of the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT), effecting of changes in domestic legislation to ensure compliance with the provisions of UNCAT and introduction of domestic law against torture and ill-treatment in line with the provisions of UNCAT.

- Ensure the strictest adherence to the rule of law and immediately put a stop to all forms of torture by the police, custodial killings, extra judicial / encounter killings etc.

- Remove requirement for sanction to prosecute police officers, military personnel and public officials from all laws and take strictest action against erring officers.

- Strengthen the law already enacted for the protection of whistle blowers.

- Full implementation of police reform provisions in line with not just the Supreme Court judgement in the Prakash Singh case, but also the recommendations made by the National Police Commission Reports.

- Ensure the establishment of Independent Directorates of Prosecutions that are monitored by the higher judiciary and are independent of the executive arm of the government.

Related:

Indian Prison Condition and Monitoring

Monitoring the condition of Indian prisons

India Justice Report 2019 highlights country’s failing criminal justice system