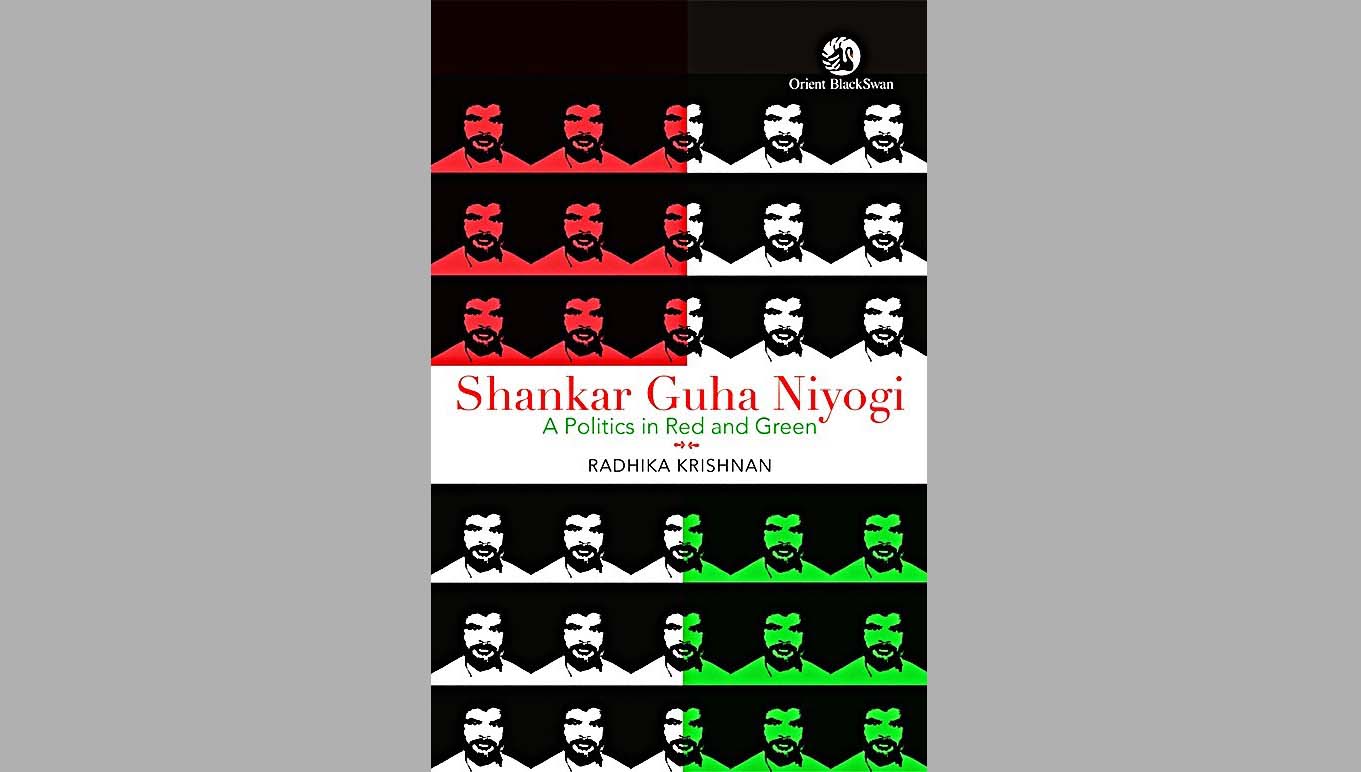

Shankar Guha Niyogi: A Politics in Red and Green, by Radhika Krishnan, is an extensive exploration of the pathbreaking ideas and experiences of a movement born in Chhattisgarh in 1977 making a case for a radically different co-relationship of labour with of ecology and technology. Founded by Shankar Guha Niyogi as a union for the miners of the Bhilai Steel Plant, the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha (CMM), representing mineworkers, factory workers, and agricultural workers across Chhattisgarh, epitomised a visionary politics dealing or paying respect not only with multiple livelihoods, but also the interrelationships crystallised between them. The author examines how this trade union intervened with wide-ranging ecological changes in the region, reinventing concepts and breaking way from the traditional conventions of a ‘trade union’.

This book unpacks Niyogi’s ideas and seeks to explore new discoveries and heights of labour’s interaction with ecology and technology. The study is a testament to tensions and contradictions being an integral part of any endeavour challenging economic, social and political backwardness.

The author explores four major aspects.

- Through resurrecting Niyogi and the CMM, the author navigates and examines how the ideological frameworks, structures and processes forge a crucial bond between labour and environment.

- Whether a worker has the capacity to be part of the process of democratising technology, or bridging the boundaries between the ‘user’ environment and the ‘developer’ environment of technology.

- Whether examining aspects of nationality and sub-nationality, ethnicity and identity hinder aspect of identity deeply rooted in labour

- Finally, whether debates around technology, environment, and nationality were a contravention of class-based trade union practice.

In addressing these questions, this book will be recommended reading for students and scholars of environment studies and labour studies.

The book explores the path breaking achievements undertaken by Niyogi. The author taps Niyogi’s visions of labour foreseeing the factory as an ecological component within the broader framework of the farm and the forest. He gives a most vivid description of the developmental debates which post-colonial India opened up which welcomed anti- people technological formats. It is a most compelling and illustrative narrative of the journey of the CMM led by Niyogi, in orchestrating the unified resistance of Adivasis, famers, peasants and workers and thus forging links between factory and forest. Most intensively it explores and dissects how the CMM planted the seeds, for a genuinely pro-people alternative of a developmental model. The book also untaps how it used semi-mechanisation to combat technology displacing labour and contractual workers forged a link with Adivasis in forests, in background of industrial pollution plaguing living conditions.

In chapter ‘A 24*7Union’ in immaculate detail it traces the historic transition of the Chhattisgarh Mukti Morcha in the backdrop of a spectrum of political events or parallel organisations and movements alongside.

The chapter on ‘Labour and Technological Changes in Chhattisgarh ‘makes a clinical and lucid diagnosis of the applicability of traditional Gandhian methods or conventional Marxist approach, and explores the creative role of Niyogi and his path breaking innovations in technology and labour methods. The book explores how Niyogi synthesised Gandhi’s ideas with that of Marx, not blindly or mechanically following either. It threw light on CMM made a major departure from economism, not merely confining itself to boundaries encompassing wages and working conditions. Ecological concerns were made an integral complement to other basic demands. Aspect of technology became a major part of the discourse. The chapter elaborated how Niyogi differed with Gandhi in utilising strike as a weapon and visualised labour as a creative, collective force in contrast to Gandhi’s vison of labour as a moral, individual duty. Unlike Gandhi Niyogi foresaw labour as capable of, innovating, interacting, creating and transforming existing structures. However Niyogi did endorse Gandhi’s critique of mechanisation and support to village technologies, in opposition to mass production of the machine. Still hands down he opposed Gandhi’s semi-feudal structures of rural economy. The chapter also invoked a detailed exploration of the economic model of Kumarappa.

Niyogi invented a Marxist method that addressed ecological contradictions and tensions and spurred workers, trade unionists and activists to re-evaluate their concept of what constitutes the working class. A critique was made of technology imported from former Soviet Union. CMM asserted that to be categorised as ‘socialist’, it had to promote labour participation in the manufacturing process, and not cause retrenchment of labour.

In Chapter on ‘Green and red Imagination’ makes a most extensive and illustrative exploration of how the CMM virtually created a new world for the workers and tribals, highlighting the abolishing of contract labour, winning rights for a fair wage, housing, free health and literacy. It elaborated how a path-breaking model had been constructed by Niyogi, with health facilities for workers transcending horizons unexplored.

In chapter ‘Chhattisgarh for Whom’ the author makes a thorough study of the nationality question and movement in Chhattisgarh. Linking it with the broader framework of political liberation and economic revolution. The experiences are located not only in their historical context, but also in the broader arena of debates on environment, science and technology, and movements for statehood and identity.

A concluding chapter ‘The Road not taken’ reflects how after Niyogi’s death after being murdered on September 28, 1991, the CMM movement strived to walk on the trail or pursue the legacy of Niyogi by keeping his ideas intact.

The work analyses practicality of Niyogi’s ideas in respect to current political and economic scenario. It navigates how globalisation and liberalisation era policies shaped the course of the CMM, recounting protests of CMM against Dunkel in 1994and 1998, jointly with farmers organisations of Punjab and Karnataka. Now the dialogue between forest and factory had sharpened with growth in process of industrialisation.

The CMM reformulated its environmental campaigns, designing posters, songs and entire campaign showcasing this theme. The CMM took an ant-war stance on Kargil after Pokhran blasts in 1998 and also formulated a powerful ant-communal agenda.

This chapter also mentions how selective memories have been obliterated of Niyogi, on environmental movements, ecological concerns and alternative technological and developmental agendas.

(The author is a freelance journalist).

Related:

Iconoclast: Path breaking biography of BR Ambedkar projects his human essence

Weavers of Banaras are forced to work for less than the minimum wage