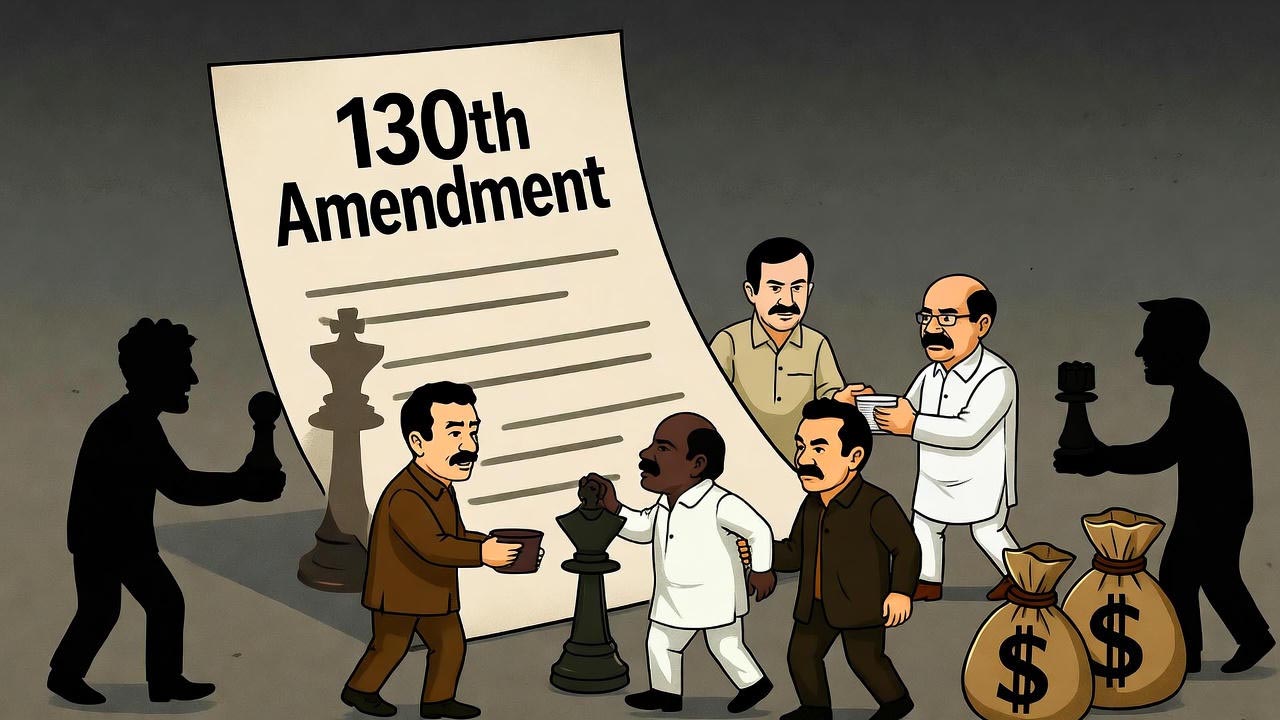

The 130th Constitution Amendment Bill is a peculiar attempt at an even more peculiar legislation. The law is peculiar because it caters neither to the principles of natural justice nor to the Constitution. What it tries to do is to cater to a surface level perception of popular morality over corruption and “criminals” getting to be politicians.

Why is it a peculiar attempt? It is so because, the bill threatens the very allies it seeks the support from, i.e., TDP’s Chandrababu Naidu and JDU’s Nitish Kumar. One might ask how it threatens the two big allies of the BJP. The Centre can unleash its institutional might on either of the Chief Ministers like it has done on both Arvind Kejriwal and Hemant Soren previously. Both chief ministers share their political turf with strong BJP partners (Pawan Kalyan in Andhra Pradesh and Chirag Paswan in Bihar) while BJP in itself is a formidable force in Bihar. For a party and establishment that boasts about its ability to make surprise decisions without any consultation, the BJP surely has given enough time for the parties to deliberate it, thus making it a peculiar attempt.

If it is a peculiar attempt at a peculiar law, why is it worth any discussion, especially when it has been sent to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC)? It is worth the discussion since such discussion will inform the views and enrich the discourse that will help in the interactions with the JPC when it invites comments over the bill.

This article presents two arguments, one that has already been well discussed and another that has been side-lined, arguably by the advent of the bill itself. The first argument is that the bill is a haphazard and harmful attempt to change the fundamental nature of criminal law and constitutionalise such harmful change while being menacingly selective, even within such harmful bounds.

The second is that the bill side-lines a crucial discussion that ought to have occupied popular discourse for a long time since governments began to topple after getting elected on a mandate: the trading of MLAs.

The Bill

The Bill proposes to amend Article 75 (by inserting clause 5A), Article 164 (by inserting clause 4A) and Article 239AA (by inserting clause 5A) of the Constitution. These articles deal with other provisions as to central ministers, other provisions as to state ministers, and special provisions with respect to Delhi, respectively.

The Bill has, essentially, four elements. One element is who comes under its scope. The Prime Minister, Central Ministers, Chief Ministers of the States and State Ministers.

Second Element is what it does. It provides that if any of the above four categories of people are arrested on charge for a serious crime for which the punishment is imprisonment for five years or more, and are detained in custody for 30 days, on the 31st day, either such person will be removed from the post or if such removal order is not given, he shall cease to hold such post from the 31st day of the custody.

The third element is how it does this. The Bill uses the high constitutional posts of the President in case of Prime Minister and Central Ministers and Governor in case of Chief Minister and State Ministers. Therefore, on the 31st day of custody, the President will have to act in the case of Prime Minister or Central Ministers, and the Governor will have to act in the case of a Chief Minister and State Level Ministers.

The fourth and final element is what happens when the person in custody gets released. The Bill essentially leaves a narrow gap for the status quo to come back. The Bill says that nothing shall prevent the person released from custody to be subsequently appointed as the Chief Minister or a Minister, by the Governor, on his release from custody.

So, simply put, if a person goes to jail for more than 30 days, they will lose their ministerial position and if they are released on the 32nd day, they will have to be appointed again.

While the bill negates all procedures for a person to be removed from office, such automated process is not there for reinstatement of those who are released from the detainment after the 31st day!!!

Seeing through the facade of Bill’s apparent upholding of Constitutional Values

The Disproportionate Nature

This section presents, at multiple stages and as one delves deeper into the reasoning behind the bill, the disproportionate nature of arresting a Minister (State or Central) or a Chief Minister or a Prime Minister.

It sounds okay if it is seen in the context of the much popularised but a fundamentally mistaken notion that all people charged with something are wrongdoers. As much stigmatizing as getting charged on something and getting arrested is, it does not prove anything. There are two data points to support this.

Firstly, more than 75% of India’s prisoners are undertrials meaning that 75 out of every 100 people in India’s prisons do not have the mark of conviction on them and yet, they are languishing in jails.

There can be further apprehensions on this saying “if they are in jail or if the police have charged them, they must have done something wrong.” It is here that the second part of information becomes useful. If this were true, out of the 548 persons arrested between 2015 and 2020 for the offence of Sedition (Section 124A) under the now repealed Indian Penal Code, 1860, there can be an expectation that a considerable percent of people should have been convicted. However, only 12 people were convicted. Sedition was given the form of ‘Acts endangering sovereignty, unity and integrity of India’ under Section 152 of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023(BNS) and it carries a punishment of imprisonment for life, or imprisonment for 7 years and fine. Therefore, if a chief minister is arrested under Section 152—the sedition equivalent—the provisions of the 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill apply if it passes through. In that case, going by how many people got arrested and thereafter convicted in similar cases, there is, at best, a chance of 2 percent for the police cases to result in conviction. And yet, going by the provisions of the bill, if they come into force, as they are now, the chief minister is ought to be removed.

Strict laws are already present

There is a chance for one more apprehension in this regard: “Isn’t that good even if 2 corrupt chief ministers do not get to be in their position?”

While the apprehension and the consequent conclusion may be a response to the eroding faith and legitimacy of the Indian political arena, the point is this: India’s laws already have provisions disallowing convicted people to contest in elections. The Representation of People Act, 1951, as a general rule provides that any person convicted of any offence, if sentenced to two years of imprisonment or more, such person shall be disqualified to stand in any election for 6 years after he/she is released from prison, after they serve their punishment. So, if a politician goes to jail as a punishment for a crime he is convicted for, not only is he restricted from standing for elections, during his period of punishment, but the restriction extends to 6 years post his release. Apart from the general rule, there are specific rules too wherein morally deplorable offences like adulteration of food, or offences under the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 attract the same restrictions even with a 6 month imprisonment conviction. Therefore, if a politician is put in jail as a convict, even for a period of 6 months under some laws, they will lose the right to stand in elections once they are released.

There are classes of offences like the offences under the laws related to Narcotics and Psychotropic substances, wherein even a fine upon conviction attracts the restriction. In that sense, the restrictions enshrined in the Representation of Peoples Act, 1951 are stricter. However, their strictness is triggered only by a conviction rather than a mere detainment.

One last apprehension is left to be dealt with before concluding argument on how selective, harmful and haphazard bills are. It is the apprehension or rather a question of “How come we have so many reports saying criminals are entering politics if the existing laws are stricter?”

This reality of people with criminal cases entering politics does not start at Chief Ministers but with MLAs and MPs. Moreover, the reports often quote the number of cases pending against the politicians rather than only convictions. While these reports would serve an argument which says that cases against political representatives need to be heard on a priority basis so that a conclusion can be attained over charges, it does not come of use to the proposition for the 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill. Additionally, this is also where the bill is being selective. MLAs and MPs are also part of Constitutional Scheme and moreover, their detainment does not affect stability of governments as much as a detainment of a chief Minister of State or a Central level Cabinet minister would. And despite this, the bill only includes in its ambit only the ministers and not all members of legislature.

Goes against entrenched Constitutional Principles

Finally, despite all this, what is the moral, constitutional and legal roadblock for the bill? It is the principle of innocent until proven guilty that not only runs at large not only throughout our criminal justice system but also our Constitution.

Where is this enshrined? Article 20 (3) of the Constitution states that no person accused of any offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself. Article 22(5) states that when any person is detained in pursuance of an order made under any law providing for preventive detention, the authority making the order shall, as soon as may be, communicate to such person the grounds on which the order has been made and shall afford him the earliest opportunity of making a representation against the order.. This means that the Constitution protects an individual against the excesses of the state and places the burden on the state to prove the guilty nature of a person.

Surely, there are some situations in which the system allows for violation of liberty of individuals like remand. However, these are not the same as an automatic removal of a Constitutional post because they are not as disruptive i.e., if a person is sent to judicial custody, they can come back and resume their daily life, which is not the case with a Chief Minister who would have been removed from office. The consistent affirmation of—bail is the rule and jail is the exception— also stresses how important the liberty of an individual is when they are not convicted. In this paradigm, it is not only perplexing but also dangerous that there is a bill which will have ministers vacate their posts once they are detained for over 30 days.

One might argue saying “what good is a chief minister if she cannot claim her post back after she is released from jail?” In the material reality of electoral bonds-electoral trusts, electoral betrayals and weaponisation of investigation agencies, we have seen the nephew double crossing the uncle, loyal ministers splitting the parties, and daughters and sisters choosing their own political journeys in opposition to their prior family-run parties. It is therefore unreasonable to expect a smooth transition of power back to the CM who would have been removed from the post while in detainment.

Under these conditions, the only purpose of the 130th Constitutional amendment bill, if effectuated, would be to increase the entropy in the Indian political arena giving an undue advantage to the already powerful forces thus weakening democratic values.

The 130th Constitutional Amendment Bill may appear to address the issue of morality in politics by disqualifying ministers and chief ministers in custody, but the real constitutional betrayal lies elsewhere—in the brazen practice of horse trading. The trading of MLAs, and the consequent toppling of elected governments, represents a far deeper threat to the democratic fabric than undertrial ministers continuing in office. The bill’s failure to address this crisis is its most glaring omission.

The Real Crisis: Horse Trading of MLAs

Since the late 1960s, India has been plagued by defections that de-stabilise governments. Legislators elected on one party’s mandate have frequently crossed over, often lured by ministerial berths or financial inducements. The 10th Schedule of the Constitution, introduced through the 52nd Amendment in 1985, was meant to curb this menace. It provided for disqualification of legislators who defected. Yet, over time, political ingenuity and judicial loopholes hollowed out this protection. Mass defections have been disguised as “mergers” or orchestrated through resignations, effectively bypassing disqualification. Recent instances in Karnataka (2019), Madhya Pradesh (2020), and Maharashtra (2022) show how easily voter mandates can be overturned without an election.

This practice amounts to a constitutional betrayal because it robs citizens of the government they elected. The principle of fixed terms under Article 172 and the collective responsibility of the cabinet under Article 164 become meaningless when MLAs can be purchased or coerced into changing sides.

Why Horse Trading is More Dangerous than Imprisonment of Ministers

The bill focuses on removing ministers in custody, but that is not the core threat to democratic stability. A minister’s detention is temporary, and in most cases, they can return to office upon acquittal or release. In contrast, once a government falls due to horse trading, the mandate is lost permanently. New governments formed in this way lack legitimacy, as they do not represent the electorate’s choice but the outcome of clandestine deals.

Furthermore, horse trading weaponises money power and state machinery. Political financiers and investigating agencies become decisive players in engineering defections, corroding not just the executive but the very legitimacy of the legislature. Compared to this, ministers in custody pose a minor problem, already addressed by the Representation of People Act, 1951, which disqualifies convicted politicians from contesting elections.

The Missing Reform: Strengthening Anti-Defection Laws

The true reform needed is strengthening the 10th Schedule. Measures could include transferring adjudication of defection cases from partisan Speakers to an independent tribunal, mandating swift decisions within fixed timelines, and eliminating the “merger” loophole. Yet, recent events show that without stronger provisions, defections will continue unchecked. Genuine constitutional morality requires insulating legislatures from the corrosive influence of money and coercion.

Constitutional Morality and Silence on Defections

By remaining silent on horse trading, the 130th Amendment Bill betrays the very morality it claims to defend. Constitutional morality requires that institutions preserve the sovereignty of the people’s mandate. When elected governments are brought down through defections, the Constitution’s promise of representative democracy is subverted. By focusing on ministers in custody while ignoring defections, the bill diverts attention from the true crisis, cloaking inaction with a veneer of reform.

Conclusion

The true constitutional challenge today is not ministers under detention but the erosion of electoral mandates through horse trading. The spectacle of governments being bought and sold has disillusioned voters, hollowed legislatures, and de-stabilised governance. The 130th Amendment Bill, by ignoring this issue, amounts to a constitutional sleight of hand—a cosmetic reform that strengthens the hand of ruling powers without addressing democratic instability. Strengthening anti-defection provisions and safeguarding legislatures from inducement and coercion is the urgent constitutional reform India needs. Anything less is betrayal of the democratic spirit and the people’s trust.

(The author is part of the legal research team of the organisation)

Related:

Liberty, Evidence and Cooperation: A legal analysis of Jugraj v. State of Punjab

A Proposal on Collegium Resolutions: Towards a single comprehensive format