n 1959, more than a third of all elderly Americans lived in poverty. Slashing that number to under 10 percent by the late 1990s was among the great U.S. triumphs of the 20th century. Social Security deserves a large share of the credit.I believe eliminating old-age poverty entirely could one day be deemed a triumph of the 21st century. Even sustaining it at 10 percent would be a significant achievement.

More elderly people may soon be pinching pennies. docent/Shutterstock.com

But that meager goal is in serious jeopardy. My research shows more Americans are increasingly struggling to save enough for their later years. And one of the main ways they have left, Social Security, is just 15 years away from going broke.

This leads me to ask one question: Do Americans want to return to a time when so many of their elders died in poverty?

A wobbly retirement

Since its advent in 1935, Social Security has been one leg of Americans’ three-legged retirement stool. The other two have been the wide availability of defined benefit retirement plans and personal savings supported by broadly shared economic prosperity.

This stool turned out to be remarkably successful by reducing the poverty rate among Americans aged 65 and older from as high as 78 percent in 1939 to 35 percent in 1959 – as Social Security benefits began kicking in – to 10 percent by 1995.

But in recent decades, the defined benefit plans and worker savings legs have become increasingly wobbly. If they break entirely, saving Social Security becomes even more vital.

Businesses shed pension risks

For much of the 20th century, defined benefit plans promised an annual lifetime payment determined by salary and played an important role in the financial security of many households with residents over 65.

Rising life expectancies required companies to pay out benefits for much longer, making them more expensive and risky. Coupled with uncertain investment returns, companies have been getting rid of them in a hunt for savings and more profits for shareholders. Only 16 percent of Fortune 500 companies offered such plans in 2017, compared with 59 percent just two decades ago.

The Department of Labor reports that the number of active participants in these pension programs as a percent of the labor force peaked in 1981 at 28 percent. Only about 9 percent participated in 2015.

Instead, they’ve shifted to defined contribution plans like the 401(k), placing the financial risk of retirement on workers.

That might have been OK, had working and middle-class Americans continued to share in the nation’s prosperity.

United Airlines flight attendants lost their defined pension plan in 2005. Reuters/Paul Yeung PY/PN

The American dream fades for many

But increasingly, that is not happening.

That’s in part because employment growth in the U.S. is now concentrated among highly skilled workers and low-paying service sector jobs, leaving fewer and fewer positions that provide enough income to set aside money for savings.

My research shows job opportunities are increasing most rapidly in positions that pay less than US$30,000 thanks to automation as well as the growing demand for personal services – and the accompanying low wages. These types of jobs do not share as much in the fruits of economic growth.

In short, the American dream, characterized by the hope that children will have a higher standard of living than their parents, is fading. Ninety percent of children born in 1940 made more than their parents at age 30, but only 50 percent of those born in 1984 had higher income at that age.

This means many more Americans will not be able to set aside much money for retirement, whether in terms of personal savings or a plan like a 401(k) or an IRA. And it’s why personal savings is the shortest leg on the retirement financial stool and it will become shorter as a result of widening income inequality.

Without more revenue, Social Security will have to cut benefits by 2034. Even if current benefits are sustained, increasing low wage employment will result in lower benefits because they are determined by lifetime earnings.

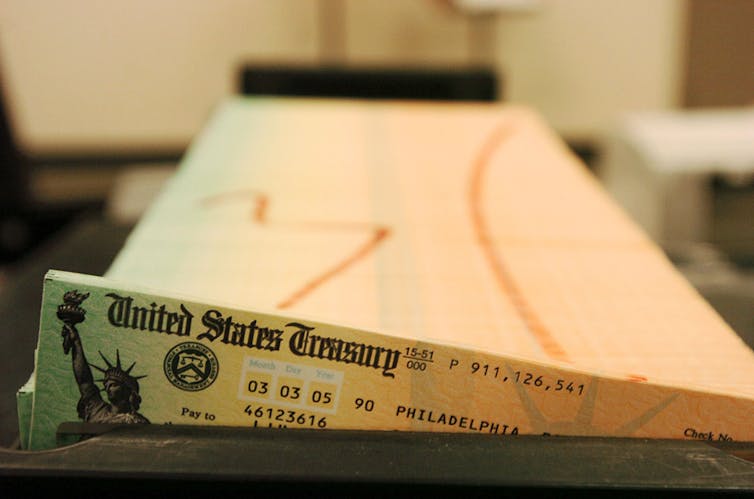

Social Security checks may get a lot smaller down the road. AP Photo/Bradley C. Bower

How not to save Social Security

That brings us back to Social Security, perhaps the last leg still standing for tens of millions of Americans as they head toward their twilight years in the coming decades. Increasing benefits for some Social Security recipients is required to avoid increasing poverty among retirees.

The system was designed so that today’s workers pay for today’s retirees. Back in 1960, there were 5.1 workers for every recipient. That ratio is projected to fall to 2.6 in 2020.

This fact, coupled with increasing life expectancy, is behind the system’s impending fiscal crisis, putting the Social Security Trust Fund into deficit.

Republicans have typically argued that the best way to fix the system is to cut benefits and encourage more workers to save through through savings plans like 401(k)s and IRAs. A bill that would erase the Social Security deficit for the rest of this century would cut benefits for 75 percent of recipients – requiring them to save on their own, which is not an option for workers stuck in low-wage employment.

The only alternative for those financially unprepared for retirement will be to continue to work into their 70s and beyond. But substantial evidence has shown that opportunities to work in the retirement years are greatest for the best-educated and highly skilled. That leaves the rest – the vast majority – in dire straits.

The result seems inevitable: More Americans will grow old in poverty.

A commitment to retirees

Whether Americans will tolerate more poverty among retirees is a political question. And I believe this debate should be about values as much as affordability.

The fact that other highly developed countries spend more to support their retirees makes clear the reducing poverty among retirees is a matter of commitment, not affordability.

So if Americans agree that our elders should never again return to having to age in poverty, there are several ways we can shore up the Social Security system.

One involves extending the Social Security tax to include all earnings: In 2018 it was levied on only the first $128,000 of income. Another is more controversial but may be necessary: use general government revenue, financed by higher taxes on the wealthy, to permanently ensure Social Security remains a bedrock of retirement.

While increasing taxes is hard, the only question is whether we have the political will to do so.

David W. Rasmussen, James H. Gapinski Professor of Economics, Florida State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.