A couple of days back, representatives of a group that wanted a petition demanding death penalty for all the accused in the Chennai gang rape case sought an appointment with me. I had clarified that I will not be part of any process demanding death penalty and would be glad to meet them on any other discussion they might want on the case. While, I managed to convince those who met me that death penalty cannot be a deterrent against rape, I suggested that instead of the petition they should spend their efforts to energize a change in the current discourse on rape in whatever small ways possible. The meeting ended with plans of a more substantive plan of action to discuss possibilities of advocating accessible spaces for children vulnerable to physical or sexual abuses at least in the neighborhood. I have summed up some of the points that I made at the discussion and I thought it would be important to share them with a wider audience.

Since Nirbhaya, rape has been at the centre-stage of public attention and anger – some of the media outlets have even started campaigns against rape while some others are more specific paying special attention to child rapes. This also helps the TRPs of many of these channels and every time an incident is reported – middle class is outraged – many times coming out on the street, sometimes even beating up and ostracizing the rapists publicly. There have been multiple outcomes of this attention – including changes in the law to assuage popular outrage – death penalty for certain kinds of rape is one of the changes. There have also been some positive changes in the law that has seen the inclusion of a variety of actions that were previously excluded that were brought within the scope of rape, inclusion of new acts of sexual assault as crimes, the process of investigation becoming more friendly at least on paper, making the character of the victim non relevant and so on. The change in law has seen special emphasis on the rape and sexual abuse of children!

One glaring lapse in all this overhauling of law is the lack of accountability of law enforcement officers. Very often rape complaints and investigations get delayed because of the lethargy or collusion of law enforcement officers and there aren’t provisions to sufficiently punish such officials for not discharging their duties. In the Panchkula gang rape case, the local police refused to register a complaint – and the survivor had to travel to Chandigarh before she could file a complaint. In rape and most sexual abuse cases, the investigation immediately after the incident is very crucial in collecting evidence and building a case against the accused. Any delay compromises the investigation apart from the mental trauma and lack of trust that the survivor has to undergo. At best these officers are suspended pending departmental enquiry, while what is needed is strict legal sanctions that will ensure that they will not shirk in their duty. Interestingly there hasn’t been much attention focused demanding that this gap be closed.

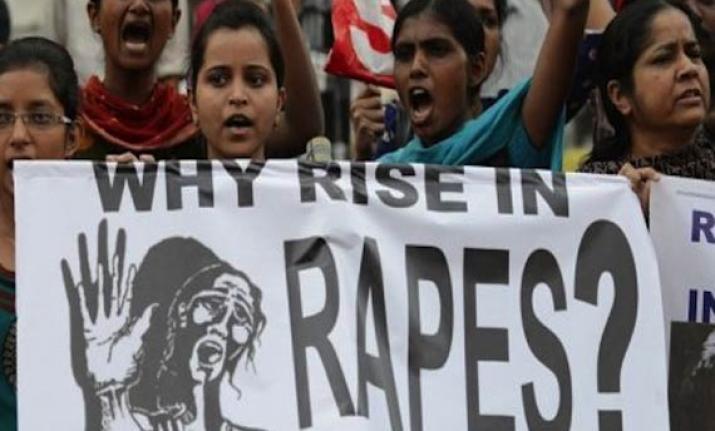

Despite all this attention, outrage and laws – nothing has changed. Rapes in general and of minors continue unabated in the most grotesque forms and media and social media are filled with graphic details of these. So, what exactly is going wrong?

The first problem as I see is that mostly rape is seen as an offence against the reputation and honor of an individual, family, community or institution and not as an offence against the bodily integrity of the person who has been raped – which includes the right of the person who has been raped to express her sexuality in whichever way she pleases. Since people are obsessed with reputation and honor, they prefer incidents of rape to be swept under the carpet as far as possible unless it becomes so violent and traumatic that willingly and unwillingly it gets exposed. In many rape and sexual violence cases, people close to and trusted by the survivor/victim are also complicit in the process of rape/abuse sometimes by their unwillingness to listen, sometimes by their eagerness to hide the incident, sometimes by their silence and sometimes by their silencing the victim. The result being endless guilt and shame for the victim and most incidents of rape and sexual abuse not being offended.

The second big problem that I see is the generalized painting of rapists as the “other”. In the reportage of most rape incidents when the rape accused are from working class or castes from Nirbhaya to the recent Chennai gang rape – the identity location of the accused is reminded over and over again – in what can be even read as a bizarre invocation of the other as the rapists. Whereas in cases where the accused is from dominant caste or class like the recent Panchkula gang rape case, the media and discussions are completely mute on their identity locations. This has created a general fear of the other as the usual rapist – which goes against all research that in most cases rapists aren’t strangers, but people known to the victims and in many cases rapes aren’t reported because of this. This also glosses over the fact that rapes are prevalent across class barriers making it appear as if rape is a working class/caste obsession. People are thereby taught to be on guard against the lesser danger of the outsider than the greater danger of the insider.

The third problem is a word that is conspicuous by its absence – patriarchy! Except in minimal circles, no one seems to want to acknowledge the connection between rape and the patriarchal need for ownership of women’s bodies. Patriarchy is so entrenched that there is a large part of the Indian society which refuses to recognize the possibility of rape within marriage – in other words that a woman doesn’t have the right of consent in a marital relationship and this view has been echoed by the judiciary. Patriarchy is so entrenched that a Delhi High Court Judge Justice Ashuthosh Kumar acquitted Mohammed Farooqui – a rape accused on the grounds that a “feeble no could mean yes” – thereby taking away the agency of the survivor to say no. Even in sexual abuses fuelled by caste or communal hatred – like Khairlanji or Kathua – the underlying reason is the idea of insulting the masculinity of the community being targeted – thereby sending them a message that they would have to undergo the worst form of punishment if they don’t toe the interests of the dominant community.

It is in this context that the sexual predator gains confidence and is emboldened about the vulnerability of the victim and finds the impunity to go ahead with her/his act – for s/he knows that the risks of getting exposed are next to minimal forget being investigated, tried and punished.

What is the way out then? It is to catch the bull by its horns. Force the discourse setters to change the discourse from one that revolves around shame, guilt, honour and reputation to one that focuses on the right to body and bodily integrity. Set the discourse straight and acknowledge the threat of sexual violence from known people. Talk about patriarchy, sex and sexuality to children – not in hush-hush or apologetic terms, but in bold, open manner – assure them that there is nothing to feel guilty about their bodies and protest if anyone whosoever it may be transgresses their bodily integrity – that they should protest and protest loudly. Make it part of their formal school curriculum. Stop voyeuristic poring over the gory details of rape and molestation and start talking about the forces that create the environment of impunity

It is definitely a long journey, but if not undertaken – the rape culture will continue unabated!

Bobby Kunhu is a practising lawyer and activist

First Publish on Kafila.online