Image: The New Leam

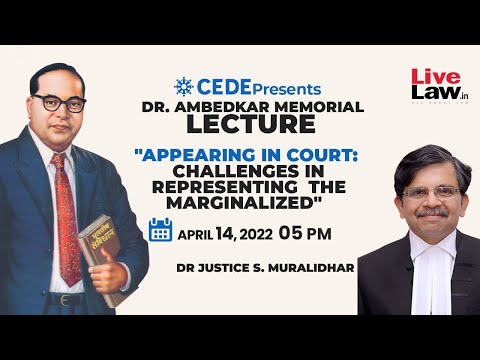

Speaking at the Ambedkar Jayanti lecture organised by Community for the Eradication of Discrimination in Education and Employment and telecast on LiveLaw on April 14, Orissa High Court Chief Justice S Muralidhar on Thursday said laws are structured to discriminate against the poor and that the system works unequally for the poor and the rich. “There are many barriers to accessing justice that a marginalised person faces,” Muralidhar said. “The system works differently for the poor. The laws and processes are mystifying even for an educated literate person. The laws are themselves structured to discriminate against the poor,” Chief Justice Muralidhar said. “Muslims and people from the Scheduled Caste and OBC communities formed the majority of those facing trials and convicted in the country,” he pointed out.

The Video may be viewed here

He made the remarks while delivering a lecture on the topic “Appearing In court: Challenges In Representing The Marginalized”, to mark the 131st anniversary of BR Ambedkar. In his lecture, Justice Muralidhar pointed out that 55% of the 3.72 lakh people in India who are awaiting trial, belong to the Scheduled Caste and Other Backward Classes, Live Law reported.

Of the 1.13 lakh convicts, 21% belong to the Scheduled Caste and 37.1% to the Other Backward Class category, Muralidhar said. More than 17% of those under trial and 19.5% of the convicts are Muslims, the Odisha High Court chief justice said.“ Yet these are the persons who are likely to find it difficult to come forward to fight for their rights,” he said.

He added that many people who are under trial continue to remain in jail despite being granted bail because of their inability to arrange surety bonds. Justice Muralidhar also expressed concern on the quality of legal aid in the country for those unable to afford legal representation.

“The lack of confidence in the legal aid lawyer is a reflection of the general approach to welfare services by the providers,” he further said. “I call it the ration shop syndrome. The poor believe that if you get any service for free or it is substantially subsidised, then you cannot demand quality.”

“The system works differently for the poor. The beggars’ courts, the Juvenile Justice Boards and the Mahila Magistrate courts are the first point of encounter for the poor with the legal system,” he said

The chief justice also cited a study that found that human rights lawyers belonging to Dalit and Adivasi were labelled as “Maoist or Naxalite lawyers”. “Their experience tells them that it [the legal system] operates to oppress them and they have to devise ways to avoid it rather than engage with it,” Muralidhar said. “We need to revive discussions around decriminalising many of the surviving activities of the poor.”

Emphasising that Constitution acknowledges persons who by birth, descent, caste and class have been denied justice over generations, he said it also envisages the State to come up with affirmative actions to redress such historic injustices. “These include those belonging to the SC, ST, Dalits, Adivasis, socially and educationally disadvantaged classes, economically deprived classes and a whole host of others, including religious and sexual minorities, differently abled and children in conflict with the law,” he said. “Then there are status offenders – sex workers, mentally ill and many others whose very existence and every activity is criminalised and, therefore, very often find themselves on the wrong side of the law. Thus, begging, street dwelling, and prostitution are all treated as law and order problems.”

“It is a matter of concern that in at least 20 states in India, there are still anti-beggary laws. Only in Delhi and J&K have these laws been struck down by judicial verdicts. Then there are de-notified tribes who have for long been the victim of police atrocities. Those coming in conflict with the law in these situations are invariably those below the poverty line and high-risk groups for whom legal aid is an absolute necessity.”

Stating that structures that marginalise a sizeable section of the population are yet to be dismantled, Chief Justice Muralidhar asserted that this is why we still have amongst us those engaged in manual scavenging, sewer cleaning or forced labour doing all our dirty work “at the cost of their dignity and right to life”.

Talking about how to meet the challenges, the Chief Justice said that the marginalised largely view the legal system as irrelevant and as a tool of empowerment and survival. “Their experience tells them that it operates to oppress them and they have to devise ways to avoid it rather than engage with it. We need to revive discussions around decriminalising many of the surviving activities of the poor,” he said.