The profound irony of Aamir is that it depicts the innocent Muslim as being terrorised by his own community

"To call Aamir a thriller would be reducing its power and ambition. The film is an eloquent statement on the state of the nation and the Indian Muslim." – Film critic Anupama Chopra

Aamir Ali (Rajeev Khandelwal), a non-resident Indian doctor, arrives in Mumbai expecting to be met at the airport by his mother and siblings. When no one shows up he calls home but no one picks up the phone. Suddenly, he is ambushed by strangers who toss him a cellphone. Aamir’s life changes. He is left to follow the instructions of the anonymous caller because, as the video clip on the phone reveals, his family has been held captive. From this time on Aamir is on the run, trying to chase the ‘Mcguffin’ that the anonymous caller sets up in order to save the lives of his family members. To cut a long story short, and consequently disclose the ‘surprise’ ending, Aamir is being trapped and blackmailed by Muslim ‘terrorists’ into planting a bomb in a crowded bus. If he fails, his family will be killed.

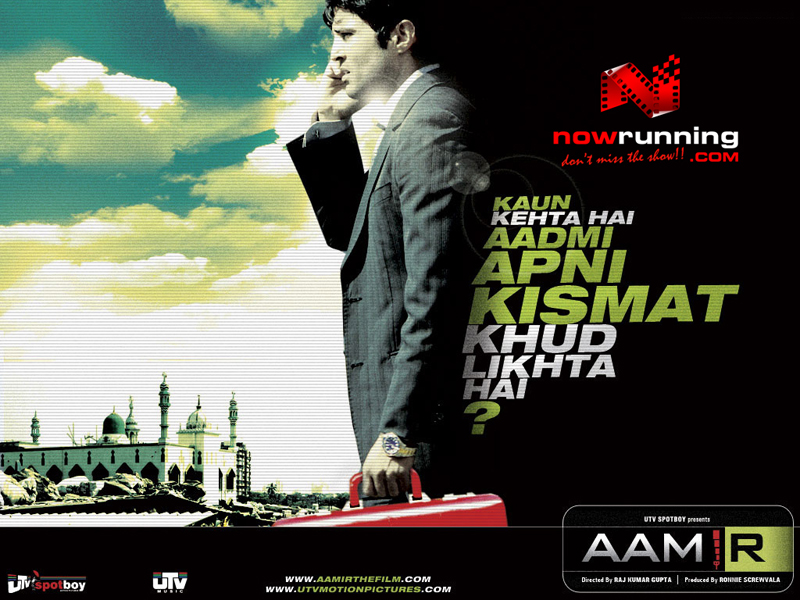

The director, Raj Kumar Gupta, describes his protagonist as a "common man" whose life changes with one phone call. Ostensibly inspired by the Filipino film Cavite and carrying resonances of Hollywood films like Falling Down and The Game, the eponymous film Aamir (2008) adopts the Hitchcockian narrative device of implicating an ordinary unsuspecting person in a series of dangerous adventures. Structured like a thriller, the film is remarkable for its gritty art design, energetic camerawork and an excellent performance by Rajeev Khandelwal as the main protagonist.

Cinéastes will be quick to notice that the visual style of the film is strongly influenced by Anurag Kashyap’s films, particularly No Smoking and Black Friday. Raj Kumar Gupta has been a close associate of Anurag Kashyap who has been credited as being the creative producer of the film. Given the film’s genre elements – the clip and rush of action, the visceral quality of paranoia and its strong visual style – it is possible that the film will be discussed primarily in relation to its craft and production values. Yet this thriller actively invites a reading of the backstory without which the central plot would be nothing but incoherent.

The entire film unfolds from the point of view of the central protagonist barring one significant exception. While Aamir never gets to see who the voice over the phone belongs to, the audience does. The anonymous phone caller who holds Aamir and his family to ransom is a dark, bald, clean-shaven mastermind who dresses in white. This shadow figure is an Islamist ideologue who, apart from providing instructions to Aamir, berates him for being oblivious to the plight of the "qaum" (community or nationhood) and leading a privileged life which includes having a Hindu girlfriend.

Operating from an undisclosed inner sanctum of safety, the ruthless manipulator denies Aamir a glass of water while feasting on an elaborate cuisine himself. Aamir only gets to eat after he has satisfactorily followed a set of instructions. The mise en scène within which the caller appears is rich with allusions. In one sequence he folds a prayer mat while speaking to Aamir on the phone. In another sequence his voice is accompanied by close-ups of a small child who sits on his lap wearing an oversized prayer cap. As his voice becomes increasingly intimidating, the child begins to cry and is promptly whisked away by a waiting woman. Ensconced in the safety of his home, this ‘bad Muslim’ is a threat not just to Aamir’s family but also his own. He stands in contrast to Aamir whose love and loyalty to his family drives him to negotiate the hellish netherworld.

For a film that relies heavily on verisimilitude, the film’s premise is strangely random. Why, for instance, is Aamir chosen to execute this particular act of political violence? Why should a militant outfit that is so well networked and resourced waste their energies (and chances of success) on an ideologically opposed man-on-the-street? Why would Aamir’s clean credentials matter in an operation where he is not expected to be caught in the first place? Why would Muslim ‘terrorists’ take sadistic pleasure in persecuting innocent members of their own community at the risk of botching up their own projects? I am not sure the film provides any clear answers.

Aamir’s frenetic journey through the underbelly of Mumbai is designed ostensibly to serve a double purpose. It is supposed to lead him to the site of the bomb blast and educate him about the living conditions of his unfortunate brethren. The working-class landscape, saturated with filth, squalor and congestion, is also a hostile panopticon where his every move is monitored by seen and unseen eyes. He is stalked, pursued and chased. Every man and woman who inhabits this shadowy nether land seems connected to the voice on the phone. The entire ‘qaum’, including a seemingly trustworthy sex worker, has been pressed into the service of ‘terrorism’.

Like the shadowy mastermind, the unmarked terrorist (no longer iconographed by the stereotypical beard and prayer cap) is dangerously anonymous and everywhere. This however does not stop the film from mobilising crude metaphors. Aamir, the hapless lamb-to-the-slaughter, is shown walking down a butcher’s lane filled with hanging carcasses. The tension is heightened with close-ups of meat being minced by cleavers. In another sequence the mastermind manipulates a toy performing monkey as he plays with Aamir’s destiny over the phone.

In one instance Aamir is told to collect ‘information’ from a filthy public toilet. The ‘information’ is contained in a tiny scrap of paper tucked into a crack in the wall. He manages to retrieve the clue after reaching across stinking human waste. As he emerges from this fetid claustrophobia into yet another squalid wasteland, he vomits uncontrollably. "Have you seen how your community lives?" the voice on the phone asks.

For the audience Aamir is both victim and hero. His heroism lies in becoming a martyr by default as he subverts the terrorist strike by choosing to die and not kill. The end is poignant for many reasons. Not least for suggesting that Aamir’s sacrifice is atonement for the political violence unleashed by his people. I have yet to see a film where Hindus are called upon to atone for the misdeeds of their community

This journey of familiarising belongs to the audience as well. Here the ‘ghetto’ is introduced in all its visceral texture; the supposed "breeding ground" of terrorism. This landscape, straddling conic Muslim neighbourhoods like Dongri and Bhendi Bazaar, embodies a millennial urban nightmare which, according to the representational logic of the film, has been authored by the violence of the Muslims.

Another situation demands that Aamir retrieve information over the phone. As instructed, he dials the number from a local STD booth. As the phone begins to ring, the sequence cuts to the location at the other end of the phone line which turns out to be a well-to-do drawing room in Karachi, Pakistan. A woman picks up the phone and tells the man next to her that it’s a call from Delhi. The man snatches the phone and grimly provides the next clue which turns out to be a hotel address. This banal slice of information needn’t have come all the way from Pakistan but it serves to reiterate the popular ‘metanarrative’ that marks all Muslims as ‘Pakistani agents’. Having made this point, the film never returns to this connection again.

After making the call to Pakistan Aamir is tailed by an ineffectual policeman who is shown to be tipped off. "Did you see how you were chased by a policeman just because you made a call to Pakistan?" asks the shadow voice on the phone. Clearly, this sequence speaks to the popular belief that Muslims have dangerous connections with Pakistan. This ‘myth’ is invoked but not debunked. On the contrary, any scepticism that one might have about such claims is swiftly subverted.

Let us return briefly to the opening sequences of the film. As Aamir lands at Mumbai airport, he encounters a prejudiced immigration officer who harasses him for no good reason except that he bears a Muslim name. Even though nothing is found in his possession, the officer repeatedly checks his bags. In exasperation, Aamir retorts that he is a doctor, not a terrorist. The immigration officer replies that whether or not one is a "terrorist" is not written on the body.

This is a common enough experience for Muslims in India and therefore it would seem perfectly logical to conclude that we are being encouraged to empathise with Aamir’s predicament. But this invitation to empathise with the central protagonist soon lands us in trouble. In an unexpected turnaround the adversaries mutate as the oppressed becomes oppressor. In a troubling, ahistorical twist Aamir becomes a victim of his own beleaguered community. The one ‘good’ Muslim in the film is pitted against a sea of demonic Muslims.

As the film moves towards its climax, the voice on the phone becomes impatient. Aamir’s encounter with his own community seems to have taught him nothing and so he is upbraided for selfishness. "If everyone is invested in self-interest then what will happen to the community?" he asks. Aamir replies that if everyone were to look after their own interests the community would certainly prosper. The irony in the film lies in Aamir’s failure to do precisely that.

After planting the bomb in the bus he is unable to make an escape and reunite with his family. He is unable to kill for the sake of his own happiness. He returns to the bus, grabs the briefcase (which makes the other commuters think he is stealing) and looks frantically to dispose of the bomb without claiming casualties. But there are people everywhere so Aamir embraces the briefcase and detonates with it. The screen is engulfed in flames as TV news reports are heard describing him as a "terrorist" on a suicide mission. The shadowy mastermind collapses on the floor in what could be seen as defeat, frustration or anguish.

For the audience Aamir is both victim and hero. His heroism lies in becoming a martyr by default as he subverts the terrorist strike by choosing to die and not kill. The end is poignant for many reasons. Not least for suggesting that Aamir’s sacrifice is atonement for the political violence unleashed by his people. I have yet to see a film where Hindus are called upon to atone for the misdeeds of their community.

The profound irony of Aamir is that it depicts the innocent Muslim as being terrorised by his own community. If the filmmaker’s intention was to acknowledge "innocent" victims like Dr Mohamed Haneef, who was falsely accused by the Australian government of abetting the Glasgow terror attack, then all that remains is the stench of burnt good intentions. The irony is no less underscored by the fact that the last decade has witnessed the rise of the Hindu Right along with an acceleration in hate crimes, including the horrifying genocide in Gujarat. Aamir’s proposition that Muslims are oppressed by their own community is a complete disavowal of history, circumstance and the testimony of brute fact.

Cinema is a phantasmic site on which desires, aspirations, fears and anxieties are envisioned. Apart from recreating external worlds cinema can access the dark recesses of our imagination and give shape to repressed phantoms that haunt our inner worlds. It is said that cinema is akin to dreams in that it encompasses our best hopes and worst fears. Films are "cultural dream works" says Ashis Nandy while Ingmar Bergman says that "when film is not a document, it is dream". Aamir is a fascinating document precisely because it is an articulation of a dream; a dream that meditates, albeit unselfconsciously, about communal prejudice. It struggles with what Mahmood Mamdani calls the idea of the ‘Good Muslim’ and the ‘Bad Muslim’. In so doing it invokes amnesia and historical forgetfulness. Therefore Anupama Chopra, whose quote I begin with, is right when she says Aamir is more than a thriller in "power and ambition". I would modify her quote to address the power of ‘unintended ambition’ and suggest that the film is "an eloquent statement on the state of the nation and the mind of the Indian non-Muslim."

Archived from Communalism Combat, September 2008. Year 15, No.134, Cover Story 1