The Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) had its baptism by fire on June 29, 2016 when it was subjected to the likes of Amit Shah, president of the ruling BJP and close associate of Prime Minister Modi, spouting venom at the memory of Jawaharlal Nehru – India’s first Prime Minister, a prominent freedom fighter, and advocate of secularism, rationality and scientific temper as foremost values in the country’s social and political life. Lokesh Chandra, NMML Director and BJP appointee, underlined the fact that “India has to change and it is no longer the world of Nehru”. The event at NMML, an exhibition and lecture on the life of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, the “selfless patriot”, was intended to accentuate the fact.

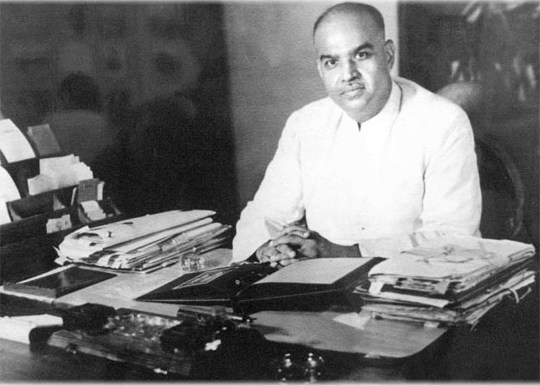

Syama Prasad Mookerjee

Shah claimed that Nehru was personally responsible for the ceasefire announced following the war in Kashmir after Pakistani forces entered the state. Shamefully innuendo’s were even held out that Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s death in Srinagar on 23 June 1953, while under arrest, resulted from Nehru’s lack of concern which was also the reason for a conspiratorial `failure’ to properly investigate it. So far the SanghParivar has observed 23 June as ‘End Article 370 Day’ and ‘Save Kashmir Day’ but this year the slogans were discarded because of the political expediency of forming a government in Jammu & Kashmir in alliance with Mehbooba Mufti’s PDP.

How factually truthful is the RSS juxtaposition of Nehru’s supposed errors with Syama Prasad’s unwavering commitment to Kashmir? As a minister in the first Cabinet of independent India, Mookerjee was party to the government’s decisions to (a) refer the Kashmir dispute to the United Nations Security Council on December 31, 1947; (b) accept the plebiscite resolutions of the U.N. Commission for India and Pakistan dated August 13, 1948, and January 5, 1949; and (c) adopt Article 370 of the Constitution as determined by the Constituent Assembly on October 17, 1949 – an embarrassing fact which Sheikh Abdullah sharply reminded him of on February 4, 1953.

When Mookerjee resigned from the Union Cabinet on April 15, 1950, there was not a word on Kashmir in his speech in Parliament on his resignation. Nor was Kashmir mentioned in his address to the annual gathering of the RSS on December 3, 1950. It was only on December 31, 1952 that Mookerjee took up Kashmir at the Jana Sangh’s first annual session in Kanpur as an issue on which communal feelings could be whipped up. To understand the logic behind this it is necessary to look at the course of Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s own chequered political career.

Mookerjee started as a Congressman and was elected to the Bengal Legislative Council as the Congress candidate. When the Congress decided to boycott the Legislature the following year, he resigned from the party to seek re-election as an independent. A diary entry of February 17, 1939, is revealing: “. . . now that age is advancing and responsibilities are increasing, I feel ever and evermore the need for a regular substantial income. I have no greed of wealth. Is there nobody who can utilise my services and pay for them? I have no chance with the Govt. of Bengal, for I am too strong a Hindu for the present powers that be, and suffer as I might, may God give me strength and wisdom to maintain my integrity and independence and not sacrifice them for money’s sake.”[Leaves from a Diary: S.P. Mookerjee, Oxford University Press, 1993.]

However in December 1941 his `strong Hindu’ identification did not prevent him from joining a Coalition Ministry with the Muslim League in Bengal. Mookerjee was Finance Minister in a government headed by A.K. FazlulHaq, who had moved the Pakistan Resolution at the Muslim League’s session in Lahore in March 1940! Mookerjee remained in his position till the end of 1942 as long as the Ministry lasted. V.D. Savarkar’s tour of Bengal in 1939 had marked this turning point in Mookerjee’s search for a political career with opportunity. The man who on August 21, 1936, had presided over a meeting in Calcutta and had lauded Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the key speaker, as “an Indian nationalist”, joined the Hindu Mahasabha. As its head, Savarkar had clearly stated: “In practical politics also the Mahasabha knows that we must advance through reasonable compromises.”

In 1942, the Quit India Movement was launched. British colonial rulers unleashed a reign of terror against the mass movement. Congress was banned, its provincial governments were dismissed, and India was turned into a jail where many died only because they had bravely raised the Tricolour against the oppressors. The Hindu Mahasabha, the RSS and the Muslim League not only boycotted the Quit India Movement but actively supported the British government in its repressive campaign. In another example of “reasonable compromise”, Mookerjee wrote to the Bengal Governor: “The question is how to combat this movement in Bengal? The administration of the province should be carried on in such a manner that in spite of the best efforts of the Congress, this movement will fail to take root in the province. It should be possible for us, especially responsible Ministers, to be able to tell the public that the freedom for which the Congress has started the movement, already belongs to the representatives of the people. In some spheres it might be limited during the emergency. Indians have to trust the British . . . for the maintenance of the defense and freedom of the province itself.”

The prominent historian R.C. Majumdar, widely held to be sympathetic to the Hindu Right, notes that Mookerjee cautioned the British against suppressing the movement only with persecution: “In that letter he mentioned item wise the steps to be taken for dealing with the situation…”

Perhaps nothing is as revealing about Syama Prasad Mookerjee’s failure to measure up to his times as the poignant account of a visit to Jirat, Mookerjee’s home-village in Hooghly District, by the renowned artist Chittaprosad who documented the ravages of the man-made famine of Bengal in great detail for the journals of the Communist Party of India, People’s Age/ People’s War, in 1944.

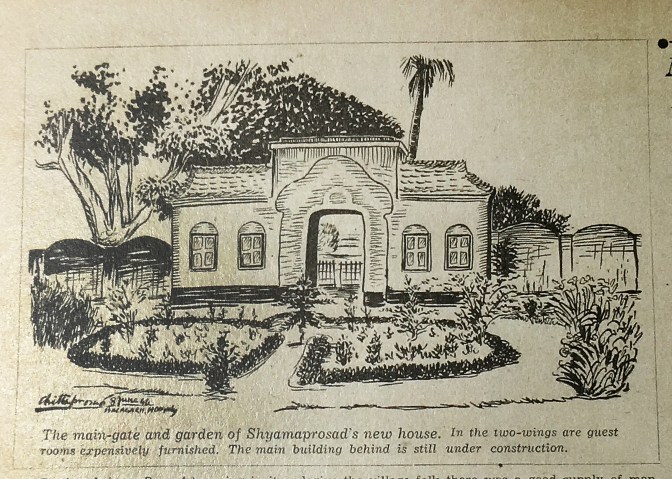

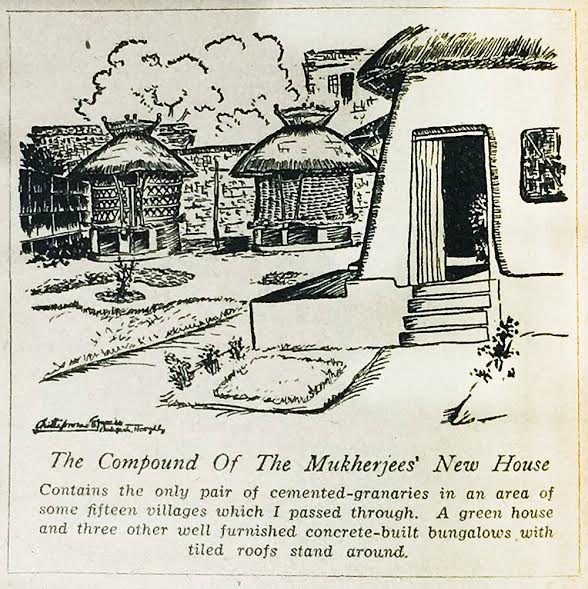

Early in June 1944, Chittoprosad cut across six or seven villages in the Balagor area to reach Jirat. What he saw was terrible. Flood, famine and a delayed monsoon had reduced the people to eating mangoes and mango seeds. His experiences are recounted in these lengthy excerpts from his article. Chittaprasad’s sketches of Syama Prasad’s newly-built house accompanied his report.

“The Riches Piled Here: An Insult to Hungry Thousands Around – Painful Sights in Shyamaprosad’s Hooghly Home Village”.

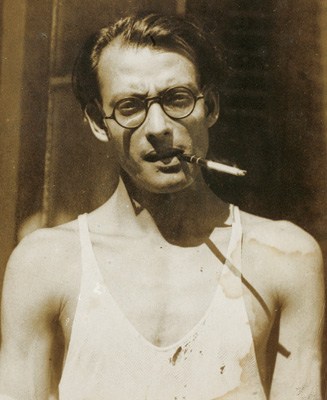

Chittaprosad Bhattacharya

“If there is any Bengali who has shot up to become a national figure in the last two years it is Dr. Shyamaprosad Mukherjee. And why not? – he is the son of Ashutosh Mukherjee, one of the builders of modern Bengal – who fought the Governor to make the Calcutta university an international centre of culture and learning. Shyamaprosad became a national figure overnight when he resigned to protest Amery’s rule in Bengal in 1943. His was the strongest voice against the Bengal Governor in the worst days of Bengal famine.

Lacs of rupees poured into his Bengal Relief Committee from the four corners of India.

Has this man who was given lacs to save Bengal kept the light burning in his own village? – that is what most people would like to know.”

“How much had Dr. Shyamaprosad done to help these villages next door to his own? – I asked people right and left. They told me how the Government had opened gruel kitchens in one village, where 400 people were fed daily for two months. How the Government had given 15 annas to each family, and a handful of chura per head in the same village. After this the Union Board also gave 14 pice to every man, 10 pice to every woman and 10 pice to every child. They spoke well of the Students Federation and the Muslim Students League, which gave cloth and 12 maunds of seeds, plenty of vegetables and a donation of Rs. 5 per family in some villages just after the flood. The Communist Party too had twice given out a pao (1/4 seer) of rice and a pao of flour per head. The DumurdahaUttam Ashram distributed Rs. 2 per household and 8 seers of atta at controlled rates for three months.

In short, everyone had tried to help, except the biggest man and the strongest organization in the district – Dr. Mukherjee and his Hindu Mahasabha.

I put the question point-blank to a prominent villager in Srikanti village: what did the Bengal Relief Committee do for them? He had not heard of the Bengal Relief Committee or of Shyamaprosad – but he understood at once when I mentioned Ashutosh. `No, we got nothing from them’ was the answer. After that I stopped talking about Shyamaprosad until I got to Jirat.

But the closer I got to Jirat, the more I realized the plight of these villages next door to Jirat. In one word, I saw what happened to a village when its natural leader leaves it in the lurch. Shyamaprosad does not help them and no one else is big enough in these parts to help them. So scoundrels and thieves steal whatever help, in the shape of food, cloth, medicines, trickles in from outside.

For instance, everyone in Srikanti village was bitter about one such man, (I refrain from giving his name), a real cut-throat who was in charge of the Union Board’s relief activity now. He doled out rice to his own favourites – at the rate of 1 ½ seers a week. But when the kisans of kadamdanga went to him for aid, he made a neat offer to them: `you cant get rice from me for nothing, you know! Work without pay in my fields, and I will sell you rice at controlled rates.’ The whole village raised a howl over this, but then he was given 15 pieces of cloth by the Union Board, to be given to 83 families in three instalments. He went back to his old game: he sent the village folk back empty-handed and made a present of the entire stock to his favourites.

One family Becomes Boss of Them All

With these stories ringing in my ears, I stepped in Shyamaprosad’s own village at last and went straight to Ashutosh’s ancient mansion. . . .But I found a sad, decayed, broken-down memorial to the `Royal Bengal Tiger’ . . . . In these ruins, Ashutosh’s sons have given a sop to those who hold their father’s memory sacred by putting up an `AshutoshSmritiMandir’ (AshutoshCharitable Dispensary). The sour-faced doctor in charge told me that he kept the dispensary open three hours every morning and 30 to 40 people come daily. But I went two mornings running and never found it open for longer than one hour. I looked for 30 to 40 patients but found only 10 to 12 when hundreds are down with malaria all round. . . .

Just when the floods were knocking down every house in Balagor – the sons of Ashutosh took it into their heads to build a brand new mansion. Old Ashutosh’s house was apparently not good enough for them.

I could not get over Shyamaprosad building a brand new mansion in the middle of the famine while his father’s house fell to pieces like every other house or hut for miles around. I went to see the hateful, vulgar, new garden-house.

The house is known all over Balagor as the only new house built in the last year and as the only house with two dhangolas stacked with paddy. . . . .There are strong iron gates and iron gratings on the windows to protect the richest spot in Balagor. . . .The whole place looks like an oasis in the desert. . . .The riches heaped here are an insult to the hungry thousands around.

I fled from the house in disgust but even then I did not hear the end of the story. The talk of the Balagor villages is of a new hat (market) – opened by Shyamaprosad with pomp and ceremony on one of his two visits home in the year of the famine.

All honest folk swear at this hat. Why? Because Balagor already had a hat of long-standing in Sijey village not far from Jirat. One hat was enough – the point was to clean up profiteering in it and give the village-folk a square deal. . . . But when I went there I did not find a hat of the ordinary sort. It was only two months old, but there was a good supply of mangoes, and some potatoes and onions too. Some paddy had come from Burdwan. They told me that 30 or 40 cartloads of paddy came twice a week from Burdwan district next door to Hooghly. The police who keep watch at the outposts of Burdwan let the carts through in return for a bribe of Rs. 5 per bag. Where does the Burdwan rice go? Some of the better-off peasants in Balagor did buy some of it. But how could they hope to win, in a cut-throat competition with the big traders from Nadia and the rice mills of the 24 Parganas? Balagor villagers got a few bags but the lion’s share is drained out of Hooghly district by rich outsiders who bid up the price of rice from Rs. 8-14 per maund to Rs. 9-8 per maund while I was there.

There is a scandal over sugar too in Jirathat. You get it only at the cut-throat rates of Rs. 2 to Rs. 2-4 per seer. Why? A shopkeeper whispered the inside story into my ears. `How can we sell cheaper?’, he asked. `You can only get it by kow-towing to the maid-servants or the housewives of the bhadralok (middle-class) families. They won’t give it for less than Rs. 1-12 per seer’. Why did they have to get round the wives and servantsof the rich? Because the babus get sugar from Calcutta and store it up. It is beneath their dignity to trade – so they make their wives pull off a bargain on the sly. They get the cash and there is no blot on their reputation – neat trick, isn’t it?

The reality of Mahasabha Relief Work

With this kind of profiteering going on in broad daylight in the hat opened by Shyamaprosad, I didn’t expect to be impressed by the relief activity of the Hindu Mahasabha in Jirat village. But I went along all the same because Jirat is the only village where people seem to have heard of relief work by Shyamaprosad.

I found this relief work to be as much a racket as the hat and the `charitable dispensary’. Once a week it seems 28 seers of atta and 28 seers of rice used to be distributed by the Hindu Mahasabha through 4 relief centres. Apart from this Shyamaprosad’s two brothers set up a shop and sold rice at half the market-price. But this did not help anyone because the market rate at that time was Rs. 40 per maund! That is why the poor peasants and fishermen of the village told me, `All charity was for the babus. Charity bought for Rs. 20 per maund was too expensive for all except a handful.’

This is roughly what I found out in Jirat, Shyamaprosad’s home village. I have been to many villages in Bengal which were homes of our great men – nowhere have I seen so much hatred and bitterness against the rich and specially against the biggest man of the village.

But on my way back I found out something more for which I was not prepared. It seems a whole generation of middle-class youth have taken to brazen-faced lying to glorify their `leader’ – Dr. Shyamaprosad Mukherjee!

Everyone in Balagor and Jirat had told me that Shyamaprosad had not come to Balagor more than twice in the last two years – once during the famine and then again to open the Jirathat. And yet a doctor I met in the neighbouring village Kasalpur told me that Shyamaprosad was coming and going from Calcutta all the time – `four times in the last two months – there is a man who loves his village.’

BimalenduGoswami who controlled rice and flour distribution at the Jirat relief centres told me that he gave out relief only on Sundays. But a young High School student who was proud of the Hindu Mahasabha told me that 24 students worked daily at the relief centres to feed 100 to 150 mouths daily!

The rich have thus made themselves hateful in Jirat – and Shyamaprosad is hated and feared more than anybody else. But at the end of my visit, I heard a few words which showed that the ancient civilization of Bengal and the spirit of Ashutosh still lives, in spite of Shyamaprosad and all his doings.

It was evening and the boys and girls had gathered in noisy groups under the trees in front of the school-house which had been locked up. Somebody started cursing. At once, an old man barked: `Who is using bad language? Have you all become animals or what?’

`How can they be human, when even the school has been closed down?’ answered somebody.

Then they all approached my guide, a kisan worker and said: `Give us a school-master please! We shall starve and give him our own food.’

`Kerosene cost 10 annas a pint, but we shall pay for it somehow. For God’s sake let the school start again. If we don’t get our school open, civilization will go out of Ashu’s village and our children will grow up hooligans.’

What an iron will to live and labour! They will live and fight as the Royal Bengal Tiger fought – in spite of Shyamaprosad.”

[People’s War, Sunday, August 6, 1944. Vol. III. No. 6, page 4.]

We have reproduced large parts of Chittoprosad’s article so that our readerscan learn from the truth of our history and not be confused by the distortions and lies being propagated by the ideologues of the SanghParivar. We condemn the RSS and the SanghParivar for the fact that they played no part, direct or indirect, in the Indian people’s struggle against British Imperialism. But now these organizations are claiming to the very embodiment of Indian nationhood and are imposing their idea of Indian nationalism not only onto the contemporary politics of the country, but also onto the history of the freedom struggle. The SanghParivar-led NDA government’s project of re-writing Indian history is trying to conjure up `leaders’ in the attempt to gain legitimacy for their claim that they should be acknowledged as heirs to the freedom movement.

The task of constituting a feudal, colonized capitalist society into an independent modern nation was thought of, planned and fought for by generations of Indians who struggled against exploitation and colonial oppression through local, regional, class, caste and gender movements to create a diverse and plural `national’ movement that eventually ended British imperialism. The responsibility for creating a nation is an on-going process which can succeed only if the values of the freedom struggle, expressed in India’s republican constitution, are promoted and secured.

(This article is from the forthcoming issue of Reconstructing Education for Emancipation, newsletter of the All India Forum for Right to Education)

Also read: आरएसअस/भाजपा के नए 'देश-भक्त' डॉ श्यामा प्रसाद मुखर्जी के बारे में 6 सच्चाइयां