Mushtipalli thanda, Nalgonda district, Telangana: July 6, 2017, had started as an ordinary day for 26-year-old Ramavath Challi, who had spent it picking cotton for a daily wage. However, on returning home that evening, she had found the entire thanda (tribal hamlet) gathered there, surrounding her husband Madhu’s lifeless body. “Appula baadha padaleka ayina mandu taagindu,” she told IndiaSpend on a recent November day, her voice choking. Pressured by debt, the 29-year-old had consumed pesticide.

Ramavath Challi, 26, whose husband Madhu drank pesticide after failing to repay a Rs 6 lakh debt, was part of the large contingent of women farmers from Telangana who marched to New Delhi as part of the ‘Dilli Chalo’ march on November 29 and 30. The protesters demanded a special session of parliament to pass ‘Kisan Mukti’ bills and a Women Farmers’ Entitlement Bill.

Paucity of rains had caused the cotton crop on their five-acre patch to fail for four consecutive years, and Madhu had racked up loans totaling Rs 6 lakh ($8,500), mostly from private moneylenders, in part to dig two borewells. These borewells had failed–groundwater levels have fallen drastically across Telangana–and Madhu had been struggling to repay his debt on which the interest was 24% annually.

It was only after Madhu’s death that Challi realised the extent of their debt, when lenders demanded their money back. A year-and-a-half on, Challi is yet to receive any compensation from the state government because the local revenue department has refused to treat Madhu’s death as farm suicide because the land title was in his mother’s name.

Challi has been managing the farm by herself. She expects to make Rs 20,000 this year–Rs 1,600 per month or Rs 53 a day, less than the World Bank’s $1.5 (Rs 106) poverty cut-off. The yield is likely to be low due to scanty rainfall. In a good year, the farm yields six to seven quintals (100 kg) per acre; this year, it might give just three.

In any case, the crop will have to be sold to the local seeds dealer, who gave Challi credit to buy seeds and fertilisers, at a pre-agreed price of Rs 5,100 per quintal, lower than the government-mandated minimum support price (MSP) of Rs 5,450.

Challi supplements her farm income with daily-wage work, which is only available in the agricultural season, and odd stitching jobs. “Itla ela bathakala amma?” she asks, how am I supposed to survive like this?

Challi represents the face of agrarian distress in Telangana, 55.5% of whose population earns a living from farming. Challi was among the large contingent of women farmers who marched to New Delhi as part of the ‘Dilli Chalo’ agitation on November 29 and 30, 2018. The protestors demanded a special session of parliament to pass two Kisan Mukti (Farmer Liberation) bills–the Farmers’ Freedom from Indebtedness Bill, 2018, which would give every farmer the right to institutional credit, a one-off complete loan waiver and debt relief after natural disasters; and the Farmers’ Right to Guaranteed Remunerative Minimum Support Prices for Agriculture Commodities Bill, 2018.

Women farmers such as Challi are also demanding enactment of the Women Farmers Entitlement Bill, which would give recognition to women as farmers, giving them access to land titles, water resources and institutional credit.

The march was part of a recent groundswell of agitation by farmers across India, as low crop yields–due to climate change, successive droughts, flash floods, pest attacks, etc.–and other factors such as fluctuating or less remunerative prices are making the farm economy unviable.

As Telangana prepares to elect a new government this month, IndiaSpendtravelled to five of its districts reporting high suicide rates–Warangal (urban and rural), Jangaon in central Telangana, Jayashankar Bhupalpally in the east, Nalgonda in the south and Adilabad in north Telangana–to understand the factors at play.

Telangana’s farm crisis

Telangana, the newest state of India, was carved out of Andhra Pradesh after a strong people’s movement in 2014. Its first chief minister, K. Chandrashekhar Rao (popularly known as KCR) of Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS), promised to transform it into Bangaru Telangana (golden Telangana), the most farmer-friendly state in India.

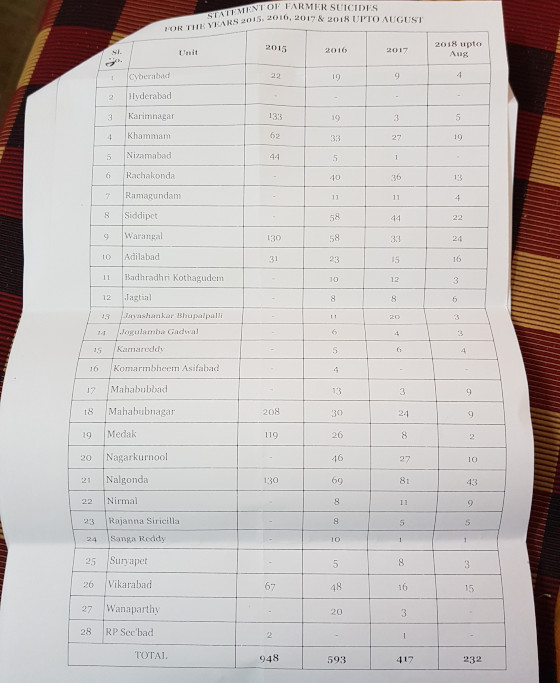

Agriculture provides a livelihood, as we said, to more than 55.5% of the state’s population. But four-and-a-half years since it won statehood, Telangana faces acute farm distress, with 2,190 farmers having committed suicide–more than one every day–according to data from the state government’s police department. The data were obtained by activist Kondal Reddy through a Right to Information request, because the National Crime Records Bureau has not published data on farm suicides since 2015.

Of these, 124 suicides took place in Siddipet district, which houses Chief Minister KCR’s constituency, Gajwel. Telangana had the third highest farmer suicides in the country after Maharashtra and Karnataka in 2015, according to data submitted by the central government to the Supreme Court.

Suicide data from the Telangana government’s police department in reply to a Right to Information request filed by activist Kondal Reddy. Between 2014, when the new state of Telangana came into existence, and 2018, a total of 2,190 farmers took their own lives. Activists, however, have recorded 3,799, 73% higher than the government figure.

State government data show a 75% decline in the number of farmer suicides between 2015 (948) and 2018 (232), but farmer rights activists say both these numbers are underestimates.

An alternative dataset compiled by Rythu Swarajya Vedika (RSV, meaning Farmers’ Self-Rule Forum), a collective of farmers’ organisations in Telangana, by collating data from police stations and from news reports, put the number between 2014 and 2018 at 3,779, of which 210 were women. Their data also show a decline between 2014 and 2018, but of 14%, much lower than the state government’s claim.

Over 89% of rural agrarian households in Telangana are in debt, the second highest proportion in the country after Andhra Pradesh, according to the Telangana Social Development Report published by the state government. The average for the rest of India is 52%. Of these, 65% have taken loans from non-institutional, private sources as government banks remain reluctant to lend without the surety of a land title. Much of this debt is used to dig bore-wells as 70% of agricultural households are dependant on groundwater irrigation, the report notes.

Farm incomes in Telangana are meagre–a small farmer (owning 2 hectare (ha) to 4 ha) earns a monthly average of Rs 4,637 from the farm and Rs 1,319 as labour, according to the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) report Income, Expenditure, Productive Assets and Indebtedness of Agriculture Households in India, 2012-2013. This amounts to Rs 200 a day, lower even than the mandated agriculture minimum wage (that is upwards of Rs 300 per day for unskilled workers and higher for semi-skilled and skilled workers).

Women bear an equal burden of farm distress, if not more. As in the rest of India, their role in agriculture in Telangana is largely hidden–women constitute 36% of cultivators and 57% of labour in Telangana, according to Census 2011. Yet, they are neither counted as farmers nor get the institutional support that comes with it. They earn unequal wages too–women are paid Rs 200 while men are paid Rs 300 as daily wages for agriculture.

Nevertheless, they work on the farm, help their husbands/families repay loans, bear domestic violence which is often exacerbated by farm losses and debt, and, if their husbands commit suicide–culturally, debt is associated with acute shame and indignity in Telangana–manage farm activities singlehandedly. All this while, they are the primary caregivers for children, the elderly and the disabled.

Unequal access to land and failure of land reforms

Farm distress in Telangana is rooted in the larger failure of land reforms and redistribution in the state, as well as a heightening unviability of the farm economy.

The average size of operational land holdings in Telangana has decreased from 1.37 ha to 1.12 ha in the decade between 2000-01 and 2010-11, indicating both demographic pressures and diversion for non-agricultural purposes, the Telangana Social Development Report says.

Large tracts of farmland are being diverted from agriculture to non-agricultural purposes–industrial corridors, real estate, special economic zones (SEZs) and ironically even large irrigation projects such as the Rs 80,000 crore ($11 billion) Kaleshwaram project, said Usha Seethalakshmi, an independent researcher who has been studying land use patterns in the state and is a member of the women farmers’ collective Mahila Kisan Adhikaar Manch (MAKAM). Celebrities and wealthy people are also known to buy large tracts of land.

This diversion has made land “a speculative commodity”, such that small and marginal farmers are unable to afford buying it, said Ravi Kanneganti, a trade unionist and state convenor of RSV. Meanwhile, the number of tenant farmers is increasing.

Further, the state has completely failed to implement the Land Ceiling Act, 1973, which caps ownership at 18 acres for “wet land” (with some form of irrigation) and 54 acres of dry land, Kanneganti said. Land ownership remains concentrated in a few hands.

As a result, medium and large holdings (4 ha to 10 ha, and above), which constitute 3.3% of the total operational holdings, are spread over 19% of the state’s land area. Marginal holdings (below 1 ha) constitute 62% of all holdings but occupy 25% of the land, according to the Telangana Social Development Report.

Of rural households, 43.3% are landless. The scheduled castes, which constitute 15.5% of the population, operate 9.6% of the land. Women, with 22.38% of operational land holdings, operate 19.6% of land, according to the latest agriculture census. Women’s average holding size is 1.02 ha, while men’s is 1.14 ha.

The link between land ownership and farm suicides is evident from a study by RSV and Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) released in 2018, which investigated 692 farm suicides in 23 districts. It found that 92.5% of farmers who had taken their lives were landless, small or marginal farmers.

The government’s response to unequal access, especially for the scheduled castes, was to distribute three acres each among dalit (ranked lowest on the Hindu caste hierarchy) families under the Land Purchase Scheme–the state would buy land costing up to Rs 7 lakh per acre and distribute it among landless and small landowning dalit families. Of the promised 900,000 acre, 14,620 acre (1.6%) were distributed among 5,759 households in four years.

“None of the dalit families in this village got a single acre of land as KCR had promised. Forget small landowners like me who have half an acre, they did not even give to the landless dalits,” said Naresh, a young dalit resident who gave only one name. He lives in Gogilapuram in Chandampet mandal, one of the poorest mandals (equivalent to a block, the middle tier of rural local governance in Telangana) in Nalgonda district.

Such schemes are impractical, Kanneganti said, suggesting that the state should redistribute land by strictly implementing the Land Ceiling Act. “Unfortunately, land reforms and land redistribution have gone out of the political agenda,” he said, adding that political parties promise small welfare measures without attention to income, food and livelihood security.

More tenancy, fewer benefits

The Hyderabad Tenancy and Agricultural Lands Act, 1950, which applies in Telangana, prohibits renting out of land. However, over the last decade, unequal access and fragmentation of holdings have forced farmers, particularly small and marginal ones, to rent larger tracts to make a viable living from agriculture.

Tenancy holdings increased from 4.7% of total operational land holdings in 2002-03 to 20.1% in 2014, according to the Telangana Social Development Report. Leased area constitutes 14.8% of total operational area, up from 3.1% in 2002-03. Other backward castes (OBCs) and scheduled castes operate the highest share of tenancy area, at 16.3% and 14.6%, respectively.

Without titles, tenant farmers are denied all forms of institutional support such as crop benefits–loans, insurance, subsidies and government input schemes such as Rythu Bandhu, the government’s flagship input support programme which offers Rs 8,000 per acre to land-owning farmers. “A farmer with no land title stands to lose Rs 50,000-100,000 per annum,” said M. Sunil Kumar, adjunct professor and advisor at the Center for Tribal and Land Rights, NALSAR University of Law, and a former state director of the US-headquartered non-profit Rural Development Institute (now called Landesa).

Ramavath Lakya, of Ramavath thanda in Nalgonda district, whose son Ramavath Shankar hanged himself in 2017 for failing to repay Rs 9 lakh in debt. Shankar owned 1.5 acres of land and took another 15 on tenancy. Despite strict laws against tenancy, Telangana is witnessing a large increase in the number of tenant farmers. Without titles, tenants get no government benefits or bank credit.

Tenancy charges are as high as Rs 15,000-20,000 per acre in the rich black soils of Warangal and Adilabad regions suitable for cotton. In the less conducive and irrigation-poor regions of Nalgonda and Mahbubnagar, it varies between Rs 2,000 and Rs 5,000 per acre. Since the rent has to be paid at the start of the agriculture season, and banks do not lend to those without land titles, tenant farmers are left at the mercy of private, often usurious, moneylenders.

It is no surprise that 75% of farm suicides were by tenant farmers, as the RSV-TISS study found. More than half the tenant farmers who killed themselves owed upto Rs 4 lakh to private moneylenders. Since they had no outstanding bank loans, they did not qualify for loan waivers by the government.

In a first-ever experiment in India, the government of undivided Andhra Pradesh had in 2011 enacted the Andhra Pradesh Land Licensed Cultivators Act, which provided loan eligibility cards (LECs) to enable tenant farmers to access crop loans and other benefits.

The Andhra Pradesh government had set a target of giving 419,412 cards to the Telangana districts in 2013-14 but gave only 43,000, as per RSV data. While there is no exact count of tenant farmers in the state because the data are not collected, farmers’ rights activists say the target number is a fraction of the number of tenant farmers in the state. The Telangana government gave fewer LECs every year except in 2016 when it gave 43,669 cards–none in 2015 and fewer than 12,000 in 2017. In 2018, only the Adilabad district administration gave 5,000 cards.

“Even with LECs, banks are not very keen to give loans to tenant farmers without the security of land titles. Banks are not willing to take the risk since the LECs are valid for a year [only],” Kondal Reddy, a farmers’ rights activist based in Hyderabad, told IndiaSpend.

How farming is becoming unviable

In 2016, 38-year-old Itikyala Sudhakar and his 35-year-old wife Jyothi of Narsakkapally in Warangal (Rural) district shifted to sowing chillies from cotton, after seeing their neighbour’s chilli crop fetch Rs 13,000 per quintal in 2014 and Rs 12,000 in 2015, with assured procurement from the corporate group ITC.

The couple harvested 160 quintals from the eight acre they cultivated as the yields that year were an unprecedented 20 quintals per acre. That year, prices crashed to Rs 1,000 per quintal (there is no minimum support price for chilli). They had racked up debt of Rs 6 lakh, of which Rs 50,000 had gone to pay just the labour to harvest the crop.

The couple were unable to sell their crop due to the glut of chillies in the market. Having nowhere to store his crop, Sudhakar dumped the chillies in the field, went home and hanged himself.

Itikyala Jyothi’s husband Sudhakar hanged himself in 2017 after their bumper chilli harvest fetched Rs 1,000 a quintal, as against Rs 13,000 the previous year. Fluctuating market prices and failure to get Minimum Support Prices are among the reasons why farming is becoming unviable, especially for small and marginal farmers, in Telangana.

In addition to fluctuating prices, farmers must contend with scanty rainfall and pest attacks, which result in low yields and contribute to making agriculture unviable.

Telangana is largely dependent on rainfed agriculture, where kharif (June to October) is the major cropping season. However, 23 of the last 30 years have witnessed drought, according to agriculture statistics published by the Telangana government.

As a result, 70% of agricultural households rely on groundwater, incurring debt to dig tube wells and dug wells, the Telangana Social Development Report says.

Groundwater levels have fallen, not the least due to overdrawing encouraged by free 24×7 power for farmers.

Access to irrigation is unequal. Only 25.5% scheduled caste and 29.9% scheduled tribe households have access to irrigation, according to the Telangana Social Development Report. Farmers allege reservoir waters are diverted to politicians’ favoured constituencies, at farmers’ cost. Irrigation projects, too, are allocated for politically chosen areas, they allege.

Experts have questioned the claims of flagship irrigation projects such as the gigantic Kaleshwaram project, saying its irrigation potential is much lower than the government claims.

Mission Kakatiya, a minor irrigation infrastructure development programme that aims to restore tanks and strengthen community-based irrigation, however, got a positive evaluation report by NABARD Consultancy Services, which said the project had increased irrigation intensity by 45.6% over the base year. However, the Comptroller and Auditor General’s compliance audit found the target of restoring 20% of tanks in three months to be unmet and unrealistic.

All in all, government programmes have proved insufficient, at the least. Given the paucity of water, the state’s cropping intensity (number of crops sown on the same field during one agricultural year), at 116%, is lower than the Indian average of 137%. And crop yields are frequently affected.

This year, the yields of cotton, the major crop, have been poor due to poor rainfall, and farmers find the crop unremunerative even though prices this year, ranging between Rs 5,250 and Rs 5,300, have been higher than the Rs 4,250 in 2017.

“Unless we get a yield of 6-7 quintals that sells at a price of 6,000 rupees per quintal, it is not viable for us,” said Ramji, a cotton farmer of Angudipeta thanda in Nalgonda district. In a rare good year, the yield goes up to 10 quintals per acre, according to the agricultural statistics data.

In contrast, in Adilabad district, 160,000 acre of crops, mainly cotton, were washed away by severe floods in August this year. “We usually pick cotton three times in a year. This year, there is no third picking, which we usually do around Sankranti [a harvest festival celebrated in January],” said Bhoomanna, a middle-aged cotton farmer in Dhanoor village in Adilabad.

Moreover, pest attacks such as the pink bollworm have been ruining the cotton crop in Telangana for the last three years. Last year, according to estimates by the district administration of Adilabad, 20% of the cotton crop was lost. Paddy farmers in Dharmasagar reservoir area in Warangal said the pest had ruined half their crop.

Farmers also have to contend with faulty seeds and fake pesticides. In Ambala village of Warangal (rural), 30 farmers who bought 70 bags of paddy seeds on the same day from the local agriculture cooperative saw 60 acre of paddy crop fail due to faulty seeds. The farmers have been holding weekly protests in front of different offices, including their local MLA and state finance minister Etala Rajendar’s home, with little result.

“Meeku super-fine biyyam pandichedi, memu control biyyam tinedi,” said U. Omkar, a 30-year-old farmer from Ambala who tills five acres of land on tenancy, meaning, “We grow super-fine rice for you while we eat subsidised rice from the public distribution system.”

Why farmers are not getting MSP

“Every government only talks of crop loan waivers, which are useless for farmers like us,” said Chirra Erranna, a tenant farmer of Guthpala village in Adilabad. “What we need is agriculture investment support and fair prices for our crop.”

The problem with MSP is that it is not a statutory but a suggestive price, Kanneganti of RSV explained, “In reality, the price a farmer gets is decided by the private players in the market yards. Because of the credit that farmers take from informal sources, they end up selling to the private traders even before the produce reaches the market yard.”

Only government agencies such as MARKFED, National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation Of India Ltd (NAFED), and Cotton Corporation Of India (CCI) procure at MSP from the farmer. Even then, they do not buy the entire produce.

“CCI does not buy more than 10% of the cotton crop directly from the farmers,” Chander Rao, a farmers’ union leader and advisor to the Commission on Agricultural Costs and Prices based in Warangal, told IndiaSpend. In Warangal’s Enamamula market yard, Asia’s second largest, CCI procured not more than 500,000 quintals of the total 50 million last year, he said.

Cotton crop being loaded onto trucks to be taken to Warangal’s Enamamula market, the second-largest cotton market in Asia.

One reason farmers are unable to sell to CCI is that it procures cotton with moisture content between 8% and 12% (with the price falling with rising moisture content). Cotton rejected by CCI is sold to private buyers at much lower prices.

The latter have their own ginning facilities, Rao said, where they make cotton bales and sell to the CCI. The entire market is controlled by a few private players, he added.

“In Warangal’s market the entire cotton trade is in the hands of a mere 100 traders and commission agents, who are in turn funded by just two or three investors, mostly Reddys and Komatis [trader caste in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana]. They decide who the farmer can sell their crop to,” said Beeram Ramulu, a farmers’ rights activist based in Warangal.

Last year, private buyers bought the cotton rejected by CCI at a price ranging between Rs 2,500 and 3,000 per quintal. CCI had procured it at an MSP of Rs 4,320 in Warangal’s market, Ramulu added.

The Telangana government has not earmarked a budget for ensuring MSP in the state, Kanneganti added. “Earlier, Rs 500 crore was allocated to MARKFED to procure produce at MSP. This year, MARKFED can only procure if it applies for loans from banks. Else farmers have no choice but to sell to private traders,” he said.

Why farmers find Rythu Bandhu inequitable

To alleviate farmers’ situation, chief minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao announced two flagship schemes in April 2018, Rythu Bandhu and Rythu Bima.

Rythu Bandhu, a Rs 12,000 crore ($1.7 billion) scheme, gives Rs 8,000 per acre (in two equal instalments) as input support to farmers. Rythu Bima, a life insurance scheme, provides compensation of Rs 5 lakh to the family on a farmer’s death, irrespective of the cause. Some 5.7 million farmers have received Rythu Bandhu support, as per state government data.

As necessary as the schemes are, Rythu Bandhu and Rythu Bima can only be availed of by farmers who have land titles reflected in government records. A large category of farmers–tenant farmers, women farmers without titles, ‘Podu’ farmers who have been farming on forest lands for many years without titles, those farming on endowment lands as tenants and Scheduled Tribes who have not received titles under the Forest Rights Act (FRA)–are excluded.

With uniform investment support for small and large farmers alike, as opposed to progressive support where smaller farmers would get more, the scheme ends up benefitting large absentee landowners who reside outside of villages and for whom farming is not the primary source of income.

Tenant farmers in Angudipeta thanda are angry at the state government for excluding tenancy lands from the Rythu Bandhu scheme. “Who is this support scheme for?” they ask. The flagship input support scheme excludes all farmers who do not own land–tenant farmers, women, podu farmers, etc.

“The government calls this ‘Pettubadi Sahayam’ [input support]. So who should get input support? Those who are making actual investments on the farm or those who are sitting in Hyderabad?” said Ramji, a farmer of the Lambada community who goes by one name, in Angudipeta thanda in Nalgonda. Ramji owns one-and-a-half acres and has leased 12 more to grow cotton. He received Rs 6,000 under the scheme as a first tranche, while his Reddy (landowning caste) landlord got Rs 48,000, he said.

“Just like these landowners take away crop loans and benefits of insurance schemes because they have land in their names, while we do all the work, they are enjoying Rythu Bandhu support also,” said Bhoomesh, a farmer from the Gond community in Indravelli town in Adilabad.

Farmers say the money offered is also inadequate.

“I got Rs 2,000 for the half an acre I have on my name. It is not enough to cover the ploughing costs of Rs 4,000 an acre and I need to plough my field three times before sowing cotton,” said Challi, the farmer from Nalgonda.

The government, while linking the scheme to land ownership, had hoped that big landowners and landlords would pass on the input support to small farmers, especially tenants who operated their lands.

“If KCR thinks the big landowner is passing on the Rythu Bandhu money to us tenant farmers, then he needs to get out of Hyderabad and come here,” said Jakka Malakanna of Dhanoor village in Adilabad, “The landowners have instead increased the lease rates from the next season. I used to pay Rs 12,000 per acre, now they are asking for Rs 14,000.”

This was a common story that angry farmers told across all the districts IndiaSpend travelled to.

There is enough demand for land from small and marginal farmers, and the landlord knows it. “He simply says, ‘Chesthe cheyyi lekunte ledu [Take it or leave it]’,” said Rajeswar Reddy, a big farmer who owns 15 acres in Dhanoor village of Adilabad and is a member of the local unit of the Communist Party of India.

The ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS), in its manifesto for the upcoming election, has promised to increase support under Rythu Bandhu to Rs 10,000 per acre, but has not said anything about including tenant farmers.

In its 2014 manifesto, it had promised to complete a land survey exercise as land records had not been updated since the 1930s. On coming to power and to facilitate implementation of Rythu Bandhu, the government undertook an ambitious Land Records Updation Programme (LRUP), under which revenue records were updated and fresh ownership titles issued to 5.7 million landowners.

Yet, many titles remain to be updated or awarded. For instance, numerous small and marginal farmers who inherited land have been unable to have the titles transferred from their parents’ names to their own. This procedure takes upto a year and numerous visits to the local revenue offices, Sunil Kumar told IndiaSpend.

Many villagers said they did not even know about the updation programme, and others alleged that village revenue officers, instead of involving the community, had updated records in an arbitrary manner, often sitting with an influential person in the village.

IndiaSpend met a group of 50 farmers in Dhanoor village in Adilabad who had not received any benefits under Rythu Bandhu, despite having land titles reflected in the new ‘Pattadar Passbooks’ issued to land holders by the state government.

“If land records purification was the end goal, it should have been done differently–in phases with community involvement. The government did it on a mission mode for the Rythu Bandhu scheme and ended up excluding a lot of people. The new government needs to settle it as soon as possible, else a lot of small and marginal farmers will suffer,” said Sunil Kumar of NALSAR.

(Rao is an independent researcher based in Hyderabad.)

Courtesy: India Spend