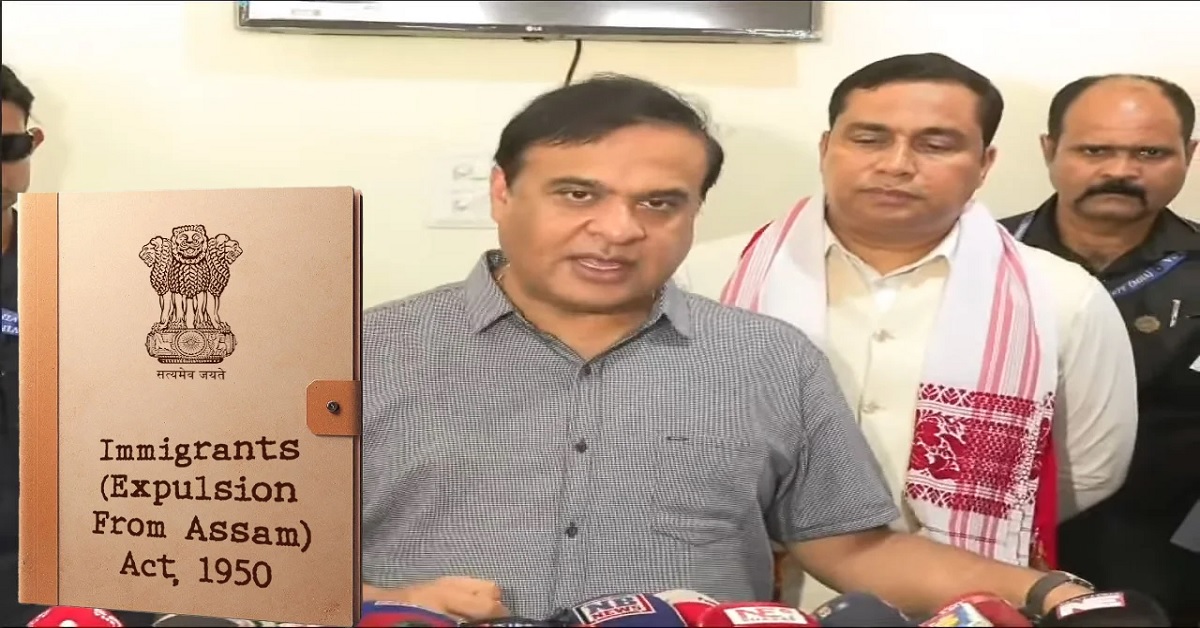

In past weeks, chief minister of Assam, Himanta Biswas Sarma has made various unsubstantiated statements “justifying the union and state government’s unlawful expulsion of persons beyond borders. Given these multiple claims, this article examines and analyses the interpretation of these actions, justified by invoking a 1950 executive order. These ‘proclamations’ have made varied and distinct premise/justifications for the recent brutally implemented “expulsion” policy that has of late, being contained by the Gauhati high court. Orders of the court may be understood here, here and here. In the first instance selectively using the Rajubala v/s Union of India case to justify these ‘deportations’, in the second instance citing a 1950 executive order (see below) as a basis for the action and in the last even brazenly stating that “inclusion in the National Register of Citizens” of a person would not deter the state from expelling him out!! We have, on the Citizens for Justice and Peace website, over past weeks published several legal resources and analyses to poke legal holes in these political claims. In this article, we specifically analyse the Immigrant Expulsion from Assam Act, 1950.

The Immigrant Expulsion from Assam Act, 1950 (hereinafter IEAA) emerged from the unique and tumultuous socio-political landscape of post-Partition India. Enacted to address the significant influx of migrants into Assam, primarily from what was then East Bengal (later East Pakistan, and now Bangladesh), the IEAA was a legislative response to demographic shifts perceived as impacting the region’s economy and social fabric. At the time of its enactment, the general framework of the Foreigners Act, 1946, did not extend to individuals migrating from the newly formed Dominion of Pakistan, necessitating a specific statute for Assam which was experiencing a particularly acute situation.

Recently, the IEAA has been thrust into the spotlight due to interpretations suggesting it confers, or that the Supreme Court of India has affirmed its conferral of, extensive and summary expulsion powers upon district administrative authorities, such as District Collectors or Deputy Commissioners. This interpretation, notably articulated by Assam’s Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, posits that these authorities can expel individuals deemed to be foreigners under the IEAA without recourse to the established quasi-judicial process of the Foreigners Tribunals. Such an interpretation implies a significant departure from the procedural safeguards that have evolved in Indian administrative and constitutional law concerning the determination of nationality and the profound act of deportation.

This article contends that such an interpretation is a fundamental misreading of the IEAA itself, is not substantiated by a careful analysis of the Supreme Court’s recent judgment in In Re: Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955 and stands in opposition to established principles of administrative law and due process.[1] This piece builds on an earlier work discussing the processes and procedures of deportation, which can be accessed here.

Far from endorsing an unfettered executive power of expulsion at the district level, the Supreme Court’s pronouncements, when read holistically, suggest an integration of the IEAA within the existing, more elaborate procedural framework for identifying and dealing with foreigners. The erratic understanding appears to arise from a selective and decontextualized reading of both the 1950 Act and the Supreme Court’s observations, potentially fuelled by a desire for more expedited executive action in a complex and sensitive domain. The timing of this re-interpretation, particularly following the Supreme Court’s judgment, suggests an attempt to leverage judicial pronouncements to legitimise a pre-existing executive inclination towards summary powers, overlooking the nuanced directives for the harmonized application of various statutes governing foreigners in Assam.

II. The Immigrant Expulsion from Assam Act, 1950: Legislative intent and provisions

An examination of the IEAA’s text is essential to understand its original scope and intended operation. The pivotal provision concerning expulsion is Section 2, titled “Power to order expulsion of certain immigrants”. This section states as follows:

- Power to order expulsion of certain immigrants.—If the Central Government is of opinion that any person or class of persons, having been ordinarily resident in any place outside India, has or have, whether before or after the commencement of this Act, come into Assam and that the stay of such person or class of persons in Assam is detrimental to the interests of the general public of India or of any section thereof or of any Scheduled Tribe in Assam, the Central Government may by order—

(a) direct such person or class of persons to remove himself or themselves from India or Assam within such time and by such route as may be specified in the order; and

(b) give such further directions in regard to his or their removal from India or Assam as it may consider necessary or expedient:

Provided that nothing in this section shall apply to any person who on account of civil disturbances or the fear of such disturbances in any area now forming part of Pakistan has been displaced from or has left his place of residence in such area and who has been subsequently residing in Assam.

The basis for such an order is the Central Government’s “opinion” that the continued presence of the individual or group is “detrimental” to specified public interests. While the formation of an opinion involves subjective satisfaction, in the contemporary administrative law paradigm, such satisfaction cannot be arbitrary or devoid of objective material; it remains susceptible to judicial review on grounds of mala fides, non-application of mind, or reliance on irrelevant considerations, particularly when fundamental rights—Article 14 and 21 in this case— are implicated. More on this is discussed in Part VI of this article. For now, let us get back to IEAA.

The Act further provides for the delegation of these powers. Section 3 of the IEAA, “Delegation of power,” states:

“The Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, direct that the powers and duties conferred or imposed on it by section 2 shall, subject to such conditions, if any, as may be specified in the notification, be exercised or discharged also by—

(a) any officer subordinate to the Central Government.

(b) the Government of Assam, Meghalaya or Nagaland or any officer subordinate to that Government.”

This provision underscores that any power exercised by a District Collector or Deputy Commissioner under the IEAA would stem from a specific, conditional delegation by the Central Government. It is not an autonomous power. The nature and scope of such delegated authority are circumscribed by the conditions laid down in the notification and the parent Act itself. The claim that District Collectors inherently possess sweeping expulsion powers under the IEAA overlooks this crucial two-step process: the primary power resting with the Central Government, followed by a conditional delegation.

Furthermore, the Proviso to Section 2 of the IEAA introduces a significant qualification:

“Provided that nothing in this section shall apply to any person who on account of civil disturbances or the fear of such disturbances in any area now forming part of Pakistan has been displaced from or has left his place of residence in such area and who has been subsequently residing in Assam.”

This proviso indicates that even in 1950, the legislature intended to differentiate among categories of migrants, offering protection to those displaced due to civil disturbances. This nuanced approach undermines any interpretation of the IEAA as an indiscriminate tool for the summary expulsion of all individuals who might have entered Assam from territories that became Pakistan. It suggests a legislative intent sensitive to humanitarian concerns, even within an Act focused on expulsion.

The original legislative intent, as contextualized by the Supreme Court, was to address a specific gap: the Foreigners Act, 1946, did not initially apply to immigrants from Pakistan (as it was then) specifically, and Assam was facing a unique migratory pressure. The IEAA was thus a targeted measure for a particular historical moment, preceding the more comprehensive and procedurally detailed framework later established by the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964.

III. Decoding the Supreme Court’s Judgment in In Re: Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955

The Supreme Court’s judgment in In Re: Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955 is central to the current debate. A careful reading of the opinions of the learned judges is necessary to ascertain what the Court actually said about the IEAA and its interplay with other laws.

Chief Justice Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud’s Opinion

CJI Justice Chandrachud(as he was then), in his opinion, provided a historical overview of the IEAA, noting its enactment was prompted by the fact that the Foreigners Act, 1946, initially did not cover immigrants from Pakistan, and that the IEAA was specifically applied to Assam to deal with large-scale immigration from East Bengal. The Foreigners Act’s limitation was due to the fact that it was enacted during the British rule and the limitation was rectified via an amendment in 1957.

This historical context is vital, as it positions the IEAA as a measure designed to fill a legislative void that was subsequently addressed by more comprehensive legal frameworks.

Justice Chandrachud’s opinion, while not having any declarations over whether the IEAA survives or not, had two crucial points.

- Parliament did not want the powers given by IEAA to be used against those who were refugees that have migrated into India in account of civil disturbances or the fear of it (Para 53).

- The act only applied to the state of Assam meaning—not only that these powers can only be granted to the district authorities in Assam, but the exercise of these powers can also only be against the immigrants in Assam and not rest of India (Para 53). This means that forcibly transporting alleged immigrants to Assam and using IEAA to deport them is not lawful.

Justice Surya Kant’s opinion for the majority

Justice Surya Kant’s opinion, on behalf of himself and Justices M.M. Sundresh and Manoj Misra, contains several crucial points regarding the IEAA.

- Critically, Justice Kant stated that the IEAA and the Foreigners Act, 1946, are not in conflict and, in fact, “supplement and complement each other within the framework of Section 6A” (Para 376). This statement directly counters any notion that the IEAA operates in isolation with overriding powers, suggesting instead a synergistic relationship.

- Referencing Sarbananda Sonowal v. Union of India, Justice Surya Kant affirmed that the IEAA, the Foreigners Act, 1946, the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, and the Passport Act, 1967, all apply to the State of Assam.[2] This reinforces the understanding of a composite legal framework governing foreigners in Assam, rather than the IEAA standing as a singular, overriding statute.

- One of the key directives issued by the Bench for which Justice Surya Kant authored the opinion is: “The provisions of the Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act, 1950 shall also be read into Section 6A and shall be effectively employed for the purpose of identification of illegal immigrants. (Para 391)“ The phrasing “read into Section 6A” and “employed for the purpose of identification” strongly suggests an integrative and procedural application. Section 6A (1)(b) of the Citizenship Act, 1955 itself defines “detected to be a foreigner” by reference to the Foreigners Act, 1946 and the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964. If the IEAA were intended to provide an alternative, tribunal-exempt route for expulsion, the judgment would likely have clarified this. Instead, its use is linked to “identification,” which is a primary function leading to or forming part of the tribunal process.

- Justice Surya Kant further opined as follows about the scope of both IEAA and the Foreigners Act, 1946:

As discussed above, IEAA is only one of the statutes that addressed a specific problem that existed in 1950. The issue of undesirable immigration in 1950 necessitated the promulgation of the IEAA and the granting of power to the Central government to expel such immigrants. On the contrary, the provisions of Section 6A have to be viewed from the focal point of 1971, when Bangladesh was formed as a new nation and an understanding was reached to grant citizenship to certain classes of immigrants who had migrated from erstwhile East Pakistan, as has been detailed in paragraphs 230 and 231 of this judgement. Hence, Section 6A, when examined from this perspective, is seen to have a different objective—one of granting citizenship to certain classes of immigrants, particularly deemed citizenship to those immigrants who came to India before 01.01.1966 and qualified citizenship, to those who came on or after 01.01.1966 and before 25.03.1971.

Since the two statutes operate in different spheres, we find no conflict existing between them. The Parliament was fully conversant with the dynamics and realities, while enacting both the Statutes. The field of operation of the two enactments being distinct and different and there being a presumption of the Legislature having informed knowledge about their consequences, we decline to hold that Section 6A is in conflict with a differently situated statute, namely the IEAA.

Instead, we are satisfied that IEAA and Section 6A can be read harmoniously along with other statutes. As held in Sarbananda Sonawal (supra), none of these Statutes exist as a standalone code but rather supplement each other. [Paras 379, 380 & 381]

Justice J.B. Pardiwala’s Opinion

Justice Pardiwala, in his dissent over the validity of Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, 1955, touches upon IEAA but not in any substantial terms.

Collectively, these opinions affirm the continued validity and operability of the IEAA but situate its application within the broader, evolved legal framework governing foreigners. There is no explicit statement in any of the opinions that the IEAA empowers District Collectors to expel individuals based on a prima facie “opinion” without reference to the Foreigners Tribunals, nor that such an “opinion” under IEAA can substitute a tribunal’s quasi-judicial finding. Such a significant departure from the established Tribunal system, if endorsed by the Supreme Court, would have necessitated clear and unambiguous language, which is conspicuously absent.

IV. Why the Supreme Court Judgment disallows an inference of unfettered expulsion powers under IEAA, 1950

The assertion that the Supreme Court’s judgment in In Re: Section 6A grants, or affirms, sweeping summary expulsion powers to District Collectors under the IEAA, thereby bypassing the Foreigners Tribunals, is not borne out by a careful reading of the judicial pronouncements. Several arguments counter this interpretation:

First, the judgment, particularly Justice Surya Kant’s opinion, emphasizes integration and supplementation, not supersession. The directive to “read into Section 6A” and employ the IEAA “for the purpose of identification of illegal immigrants” (Para 391(e)) implies that the IEAA is to function as a component within the broader machinery. Section 6A (1)(b) of the Citizenship Act itself defines “detected to be a foreigner” as detection “in accordance with the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946 and the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964 by a Tribunal constituted under the said Order”. If the IEAA were to provide a parallel mechanism that bypasses this definition for expulsion purposes, the Supreme Court would have had to explicitly state that the requirement of tribunal-based detection could be circumvented under the IEAA. No such statement is made. Instead, the IEAA’s role is linked to “identification,” which is the preliminary step that often leads to a reference to a Foreigners Tribunal for a conclusive determination of status.

Second, the power delineated in Section 2 of the IEAA is primarily vested in the Central Government. While Section 3 allows for the delegation of this power, such delegation is subject to conditions specified in the notification. Crucially, delegated power cannot be exercised in a manner that contravenes fundamental due process requirements or ignores established statutory mechanisms like the Foreigners Tribunals, especially when the Supreme Court itself links the IEAA’s contemporary use to “identification” within the Section 6A framework. The scope of delegated authority cannot be broader than the power of the delegating authority when read in conjunction with other prevailing laws and constitutional mandates ensuring procedural fairness.

Third, the Supreme Court’s affirmation of the IEAA’s validity and continued operability signifies that the Act remains on the statute books and can be invoked. However, this affirmation does not translate into a license to use the Act in a manner that disregards the specialised, quasi-judicial mechanism of Foreigners Tribunals. These tribunals are specifically established for the determination of a person’s status as a foreigner – a critical determination that must precede the severe consequence of expulsion. The interpretation that “valid and operative” means “valid for summary, independent action” is a misconstruction; the Act is valid as part of the legal toolkit, not as a master key that overrides other procedural safeguards.

Fourth, the profound implications for due process and individual liberty that would arise from granting summary expulsion powers to District Collectors, bypassing tribunals, are such that if the Supreme Court intended to endorse such a system, it would have done so explicitly and with clear reasoning. The Court’s silence on this specific point, coupled with its emphasis on the integrated and complementary application of the relevant statutes, is telling. The judgment upholds the IEAA’s existence but implicitly requires its application to be harmonized with the current, more evolved procedural framework for determining foreigner status. The focus on “identification” by Justice Surya Kant (J. Surya Kant, Para 391(e)) is pivotal. Identification is typically the precursor to adjudication by a Tribunal. If the IEAA allowed a District Collector to identify and expel based solely on a “prima facie” view, as suggested by Assam CM, the elaborate and long-standing Foreigners Tribunal system in Assam would be rendered largely redundant for a significant category of cases – an outcome the Supreme Court does not appear to endorse.

V. Harmonising the IEAA 1950 with the Foreigners Act, 1946, and the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964

The Foreigners Act, 1946, particularly Section 3, empowers the Central Government to make orders, inter alia, for prohibiting, regulating, or restricting the entry of foreigners into India or their presence therein. It is under this provision that the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, was promulgated, establishing Foreigners Tribunals specifically for the quasi-judicial determination of whether a person is a foreigner. This mechanism is central to the definition of “detected to be a foreigner” in Section 6A (1)(b) of the Citizenship Act and is frequently referenced in the Supreme Court’s judgment as the established process.

A harmonious construction, consistent with the Supreme Court’s directive to “read into Section 6A” and use the IEAA “for identification” [J. Surya Kant, Para 391(e)], would mean that information gathered or preliminary assessments made by the district administration (as a delegate of the Central Government under IEAA Section 3) could form the basis of a reference to a Foreigners Tribunal. The “opinion” of the Central Government (or its delegate) under IEAA Section 2 that a person’s stay is “detrimental,” could serve as a ground for initiating a formal inquiry or making such a reference. However, the crucial determination of foreigner status itself, which is a prerequisite for expulsion under either Act, would remain within the purview of the Foreigners Tribunals, as per the dominant legislative scheme and procedural due process.

This interpretation aligns with Justice Surya Kant’s observation that the IEAA and the Foreigners Act “supplement and complement each other”, rather than the IEAA providing an overriding, summary power that displaces the tribunal system. The Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, provides a specific and more recent procedural mechanism for the determination of foreigner status.

The IEAA, on the other hand, is broader in identifying the class of persons who can be expelled and the ultimate executive authority responsible (the Central Government or its delegate). Harmonisation suggests that the IEAA identifies who might be subject to expulsion and by whom the ultimate executive order of expulsion might be issued, while the Foreigners Act and the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order provide the process for establishing the critical precedent fact – whether the individual is indeed a foreigner. The term “identification” used by Justice Surya Kant is distinct from “adjudication” or “declaration” of foreigner status. District administration can play a role in preliminary identification (i.e., forming a prima facie suspicion), but the quasi-judicial adjudication of that status, given its severe consequences, aligns with the specialized role of Foreigners Tribunals.

VI. Jurisprudential foundations: Due Process and limitations on executive power in expulsion

The exercise of any statutory power, particularly one as impactful as expulsion, must be viewed through the prism of India’s evolved constitutional jurisprudence. Administrative law principles, especially those concerning natural justice (audi alteram partem, rule against bias) and the requirement for reasoned decisions, have been significantly strengthened by the Supreme Court over decades. An archaic statute like the IEAA, 1950, cannot be interpreted in a vacuum, isolated from these constitutional developments. The principle of “updating construction” requires that older statutes be read, as far as possible, in conformity with later constitutional norms and human rights jurisprudence. The IEAA, therefore, must operate within the current legal environment where procedural fairness is paramount.

For example, in Hukam Chand Lal vs. Union of India, the government disconnected the person’s telephones, citing a “public emergency” due to their alleged use for illegal forward trading (satta). The Supreme Court found the disconnection unlawful.[3] It held that the authority, the Divisional Engineer, failed to apply his own mind and record his own satisfaction that an emergency existed. Instead, he acted solely on the government’s declaration. The Court ruled that such drastic powers require the designated authority to rationally form their own opinion, not just follow orders.

In S.N. Mukherjee vs. Union of India, the Supreme Court addressed whether administrative authorities must provide reasons for their decisions.[4] In this case, the Court laid down a landmark principle: the requirement to record reasons is a part of natural justice. It held that providing reasons ensures fairness, prevents arbitrariness, guarantees application of mind by the authority, and enables effective judicial review.

The determination of whether a person is a foreigner, a decision that can lead to expulsion, has profound consequences for individual liberty, family life, and personal security. Such a determination inherently demands a fair, transparent, and quasi-judicial process. To contend that the IEAA allows for summary expulsion based solely on an executive “opinion,” without a quasi-judicial hearing by a specialized body like a Foreigners Tribunal, would be to argue for a procedure that is likely to be deemed arbitrary and violative of Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution. Article 21 guarantees that no person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law, and such procedure must be fair, just, and reasonable.

The very establishment and continued strengthening of the Foreigners Tribunal system over several decades signifies a legislative and judicial recognition that determining foreigner status is a complex matter requiring a specialized, quasi-judicial approach. While there are issues with the current system of foreigner tribunals, the way is not to go backward in terms of procedural fairness but to move forward to make processes fairer. This evolution points away from purely executive determinations of such critical facts, especially when a statutory framework for quasi-judicial assessment is in place.

VII. Conclusion: Upholding the rule of law and procedural propriety

The analysis of the Immigrant Expulsion from Assam Act, 1950, the relevant provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946, the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order, 1964, and the Supreme Court’s judgment in In Re: Section 6A of the Citizenship Act 1955 leads to the firm conclusion that the IEAA does not confer unfettered, summary expulsion powers upon district administrative authorities that would allow them to bypass the established quasi-judicial framework of the Foreigners Tribunals.

The Supreme Court’s judgment, far from endorsing such an interpretation, supports an integrated and harmonized application of these statutes. Justice Surya Kant’s directive to “read into Section 6A” and employ the IEAA “for the purpose of identification of illegal immigrants” [ J. Surya Kant, Para 391(e)] indicates that the IEAA is to be used as a tool within the broader framework, likely to initiate inquiries or make references to the Foreigners Tribunals, which remain the designated bodies for the quasi-judicial determination of a person’s status as a foreigner. This interpretation is consistent with the principle that specific procedural statutes (like the Foreigners (Tribunals) Order) govern the determination process, while the IEAA may provide grounds or identify the authority for expulsion once such determination is made.

The constitutional imperatives of due process, enshrined in Articles 14 and 21 of the Constitution, mandate that any action as severe as determining nationality and ordering expulsion must be preceded by a fair and just procedure. In the context of Assam, this procedure is embodied in the Foreigners Tribunal system. Any interpretation that suggests the IEAA allows District Collectors to unilaterally form an “opinion” and expel individuals without recourse to these tribunals is not only a misreading of the Supreme Court’s recent judgment but also runs contrary to the evolution of administrative and constitutional law in India. Such an approach would be detrimental to the rule of law and could lead to arbitrary outcomes, eroding public trust in the legal system’s ability to handle complex immigration issues with fairness and consistency.

The constitutionally appropriate approach is for the district administration—acting under powers delegated by the Central Government, including those under the IEAA—to identify suspected illegal immigrants and refer their cases to the Foreigners Tribunals for a quasi-judicial determination of status. Deportation may then proceed in accordance with established legal procedures, which you can read about here. This ensures a balance between the state’s legitimate interest in managing immigration and its constitutional obligation to uphold the rule of law and procedural fairness.

(The author is part of the legal research team of the organisation)

[1] 2024 INSC 789

[2] (2005) 5 SCC 665

[3] AIR 1976 SUPREME COURT 789

[4] 1990 (4) SCC 564

Related:

Seeking sanctuary, facing scrutiny: Why India must revisit its approach to the displaced

India: A deep dive into the legal obligations before “deportation”