This article uses Michel Foucault’s dialectic of the “scene” and the “obscene,” complemented by Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony, to understand how historical change in both the making and persistence of caste in India has taken place. It contends that, from being a premodern order where the logic of caste presented itself as an undivided, publicly affirmed “scene” of sacral-political hierarchy, it has become a modern condition riven by a fundamental fissure: an official and publicly endorsed “scene” of constitutional equality and liberal citizenship coexists with a pervasive if now often privatised “obscene”, in which caste is perpetuated through intimate sociality, corporeal practices and episodic violence. This bifurcation is not a dilution of caste, but its evolved form that enables its perpetuation in the regimes of modernity, democracy and capitalism. Built on historical, ethnographic and documentary evidence that has been collected from medieval inscriptions to colonial censuses, the Khairlanji massacre and corporate culture in urban India under neoliberalism, it follows a long trajectory to map the transformative changes associated with the slogan and excavates for us the political battles fought to ‘abolish’ it altogether.

Methodological Prologue: Theory as Lens, not Template

To be able to think caste within the same analytical field of reference as Michel Foucault and Antonio Gramsci— two intellectual giants who have left an indelible impression upon his generation—whose long shadows loom large over the landscape of modern Europe, demands a first-order methodological clarification. It is an undeniable premise that caste is uniquely South Asian, a totalising social system with a distinct ontology around indigenous cosmologies of purity, pollution and hierarchal interdependency. Its thinking, its historical trajectory and the experience it embodies can be only partially understood through terms drawn from European history such as class or feudalism or racism, as people like Gopal Guru, Sundar Sarukkai and Dalit Studies thinkers have never tired of insisting. To apply these categories would amount to an act of epistemic violence, the imposition of an artificial reality onto a queasy and never quite-fitting architecture that illuminates nothing but dims what appears from Indian soil, reiterating the colonial knowledge systems that sought once to solidify and regulate caste under alien rubrics. Such as it is, the critique of Eurocentrism isn’t merely an afterthought but a disciplinary sensibility tout court.

So, I provide an inversion in this engagement with Foucault and Gramsci. I am not trying to “apply” their theories to the Indian “case” (as if it were a case of universal concern) in order to fit caste into the Procrustean bed of their local historical referents (the clinic, the prison, the European factory or the making of the Italian nation-state). Rather, I seize their essential methodological insights as adaptable analytical heuristics for shedding light on an essentially novel object. Foucault’s dialectic of the scene and the obscene is indispensable if not as an explanation of European épistémès, at least for its sophisticate analytic tool for understanding how power arranges seeing and saying, produces zones of authorized words and tactical silence, articulates a frontier between what is audible and inaudible. And, once again, Gramsci’s idea of hegemony is not used as a theory of European class making but as a dynamic way to grasp the securing of domination through the construction of “common sense” and the combined action between coercion and consent. Within such a machine, theory is no longer a master narrative so much as an array of precision tools. I do this by deploying these instruments to dismantle the historically specific materiality of caste from its sacred roots to its colonial codification and postcolonial mutations making it possible for the specificity of the phenomenon itself to interrogate and remould the theoretical tools. This essay is then a thought experiment of a critical, situated translation. It deploys Foucauldian and Gramscian optics in order to illumine caste’s internal architecture, its historical transmogrification, while insisting that the image at which one arrives is thoroughly, irreducibly Indian and needs also to conjure up its own vocabulary even as it speaks a global language of power.

Introduction: The Architectonics of Invisibility

One of the most enduring and complex systems of social stratification in the world—India’s caste system (varna-jati)—is found in the Indian subcontinent. Its analysis requires tools that can penetrate not only its economic or political aspects, but its deep entrenchment in the spheres of knowledge production, body and space. Michel Foucault’s conceptually rich dyad of the “scene”, (what is made visible, sayable and governable) and the “obscene” (that structurally figured beyond but which in its beyond-ness constitutes the scene) provides a powerful prism. When coupled with Antonio Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, the means by which ruling groups achieve consent via an ideological “common sense”, this set-up reveals how power functions not just through suppression but through careful organization of social reality itself.

This paper opines that the history of caste has to be considered as a history involving managing (or mismanagement) of this scene/obscene border. The shift from premodern India to modern makes for a seismic change in such tactics of management: from an integral sacral-political scene to a fragmented modern settlement, where the official defacement of caste on real constitutional law and its attendant discourse on the public scene is the very condition for its raucous (albeit often underhand) existence in that social obscene. In it, the dominant scientific and technological discourses on which the ‘normalisation’ of modern society is based cohabits uneasily with remnants of an archaic and pre-modern social universe intricately woven into a powerful hegemonic discourse that systematically normalizes denial akin to what we have called here the hermeneutics of caste. The analysis draws from, among others, works by Nicholas Dirks (2001), Anand Teltumbde (2014) and Gopal Guru (2016) to map this transition showing that contemporary caste should be best understood as a sort of social schizophrenia driven by imaginative acts whereby power perpetuates itself through a convoluted hermetic legitimising act in India.

I. The Integrated Premodern Scene: Inscription, Spectacle and Sacral Hegemony

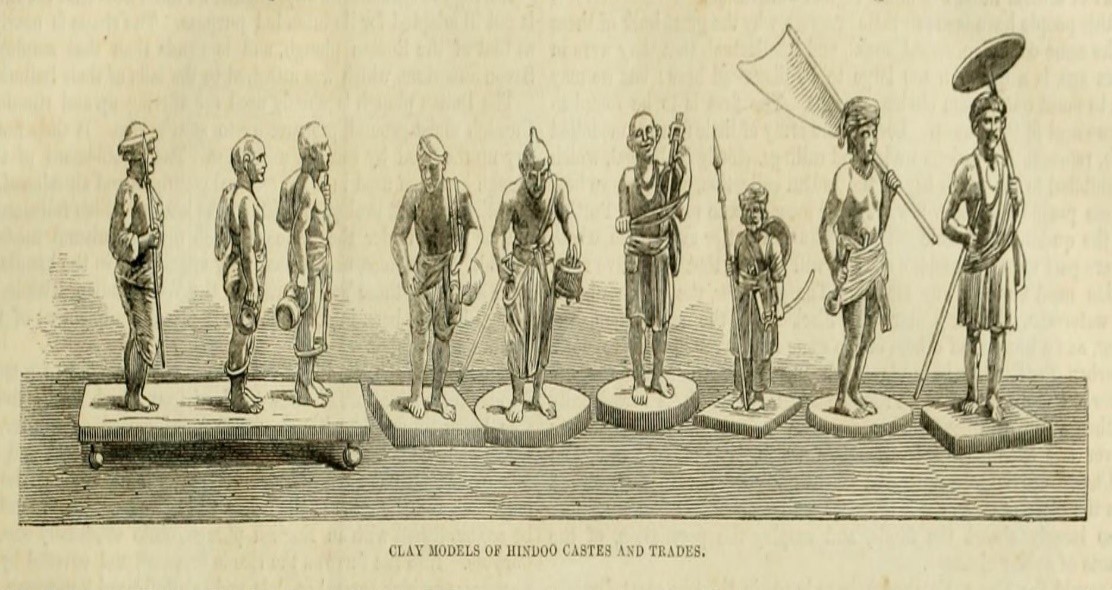

The caste hierarchy was a relatively coherent and explicit “scene” in the precolonial and early colonial environment. Its effectiveness was based on its thoroughgoing visibility and its cosmological basis. This can be felt clearly through the texts and inscriptions of medieval India.

Case of the Chola Temple Inscriptions and the Smritichandrika: The walls of the temples in Chola period (approx. 9th-13th centuries) are not just structural, but are public records of the social scenario. That act of reciprocation is documented in countless inscriptions which record the details of gifts but also control in great detail the spatial and ritual order: which castes could offer which kinds of gift, how close they might reside to the temple, and what the penal fines would be if they broke faith. At the same time, codified legal digests such as Devanna Bhatta’s 13th-century Smritichandrika continued to systematise dharma for a wide range of varnas and jatis, dictating clothing and ornaments suitable for narrow groups and stipulating edible diets or respectable partners in marriage.

They are performances of sovereign power. The law was not concealed in statute books but carved onto the holiest public edifices. That made the caste system, already a great monument to human pettiness and pride, permanently, monstrously visible. The elaborately clothed body of the Brahmin (instituted with the sacred thread, instringent in particular fabrics) contrasted with the regulated “nakedness” or coarse apparel of those belonging to “lower castes” was a wearable map of social arrangement- status could be read at once on bodies. “Conjugable” was not private, but public, scripture-regulated machinery for the perpetuation of biology and society.

This was an order that was not only maintained through coercion. It was the centre of agrarian economic and ritual life. Writing caste duties on the walls, the ruling powers (the Chola king, Brahmin sabha) attached social status to divine will and royal command. What it did was not to punish, but explain, rationalise and naturalise. It was polished over by embedding caste inside a sanctified “common sense” in which following one’s svadharma was identified with piety, social tranquillity and karmic reward. Consent was produced by the reaffirmation of ritual incorporation and cosmological tale.

An opulent calligraphy of gleaming inscriptions is what this glittering scene silences. The manual, waste-dirty work of temple purification, cleaning, and waste management, labour assigned to the lower (in caste hierarchy) communities, was the necessary but repelled root. There they were a required obscenity, consigned to literal geographical peripheries (the cheri outside the village) in order to keep unsullied, the jatra’s pure centre. The violence required to maintain this order, whenever necessary, was a public spectacle in its own right, a Foucauldian “scene” of sovereign punishment that reaffirmed the parameters of the permissible.

The coherence of this “scene” can be better appreciated, and the premodern character of it more clearly identified, by consideration to a ritual control of everyday practices that makes hierarchy in large measure visible and ever self-evident. The very access to water for instance worked as a micro-theatre of caste power. Shudras and untouchables were forbidden to draw water from a common source that the Savarna castes drank. The prohibition was not just economical or hygienic, it was dramaturgical. The distance at which awaiting castes waited to receive water from above the threshold through a high-caste intermediary enacted hierarchy as embodied choreography. Here, power did its work not by abstract law alone, but through disciplined gestures and spatial distance and the policing of touch. The practice of pollution was practised time and again on the body, making domination a matter of course.

Temple Restrictions of Entry Again, temple entry restrictions circumscribe how the holy solidified the sightedness of the field. As a condensation of the cosmic arena for legitimacy, these were the gatekeepers to those who could and could not come near divinity itself but whose mere presence would cause ritual chaos. Therefore, being kept out of temple space was not just marginalisation but rather the ontological disqualification from the moral order which organized village life. The untouchable body was constitutively “ob-scene”, that which was vulgar so as to be excluded from the sacred frame, and thus a figure of purity in the visible scene. But this exclusion, counter-intuitively, verified centrality: the system needed what it banished. Carcass removal, tanning and sanitation-labour were materially integral to the agricultural way of life, and that the obscene was not external to power but its hidden basis.

This paradox has the kind of echo that Foucault will say later, that power creates what it seemingly excludes. The untouchable was, then, not simply oppressed but discursively produced as pollutant, essential to the symbolic unity of Brahmanical purity. Visibility and invisibility therefore comprised one and the same machine. Although his labour was required to be concealed in the sacred space of ritual, it was common for punitive violence against him to become hyper-visible. Public flogging, forced parade or head-shaving was used as exemplary scenes; measures which were not so much punishments for the individual violator but white lines re-drawn in the scene for all its observers. Acts of sovereign violence, in this respect, reconfigured ritual order by sporadic eruption into theatrical display.

But coercion alone cannot account for the endurance of this structure. Hegemony in Gramsci’s sense explains how domination hardened into “common sense.” The karmic reading of suffering converted structural inequality into a moral story: One’s birth deserved, one’s duty redemptive. Most importantly, this imagination was not the prerogative solely of the dominant castes. The participation of the subalterns in ritual hierarchies, through service function in festivals, acceding to hereditary occupation or practicing endogamy indicates to what extent voluntary and coercive approaches were complementary. This was not passive belief, but lived practice that was realised through kinship, worship and toil.

At the same time, however, that premodern scene was never perfectly sealed. Bhakti movements in various regions periodically disrupted the ritual hierarchy by emphasising devotional equality and vernacular expression. Literary figures like Ravidas or Nandanar made religious claims that transcended caste lines, briefly disturbing the visibility of the status quo. Even these challenges, however, were frequently absorbed (or re-absorbed), their radical potential domesticated within particularities of tradition. This ability to absorb demonstrates the strength of hegemonic formations: protest could be recognised symbolically without altering the material basis of hierarchy.

Here, the premodern caste order is not merely a system of hardened stratification but a staged totality through which space, body, work, force and belief converged aesthetically. The Foucauldian pairing of scene and obscene demonstrates the need for purity to be premised upon exclusion, as well as how visibility became a mode of discipline, while the Gramscian lens helps us understand that the long half-life was driven by moral internalization and quotidian consent. Together they reveal a system whose stability was founded on portraying hierarchy as both sacred and natural, a portrayal that subsequent historical developments would gradually start to undo, but not without enormous effort.

II. The Colonial Interregnum: Re-Scenography, Biopower and Taxonomic Hegemony

With the beginning of colonial governance, a significant change occurred. The British colonial state, a modern bureaucratic state at work, wanted to know, categorise and govern its subjects, effectively transforming the performance of caste.

Case of the 1901 Census and Risley’s Anthropometry: The Census, especially under Superintendent Herbert Risley, turned into one of the effective colonising projects. Risley tried to confer a “scientific” legitimacy on caste hierarchy through the use of anthropometry (the measuring of nasal indexes, skull shapes and other bodily features) to construct a racial taxonomy of Indian castes. This information was then used to generate all-India rankings for caste status. This was biopolitics in the pure, administrative state. Power worked in the colonial state by treating the Indian as an object to know, measure, and categorize. The caste became a fixed category rather than the fluid groups of jati relations that it had been, as well as an enumerated and pan-Indian taxonomy, a trope of colonial “governmentality” (Dirks 2001). The muddled local logic of purity/pollution was transformed into a clean, bureaucratic chart. This gave rise to a new all-India “scene” for caste: the statistical report, the ethnographic survey, the gazetteer. The ritual body became a racialised or datafied body.

This scene of bureaucracy had far-reaching hegemonic implications. In cataloguing (and ranking) castes so consistently, the Census rendered new identities that groups came to accept even as they fought them. It laid the groundwork for caste-based political organisation, as represented in the Non-Brahmin Manifesto of Madras (1916) or in the demands for separate electorates. The strategy of the colonial state was one of “divide and rule,” but it did so by offering the vocabulary, among the enumerated caste identity, through which political claims could be made. It fragmented older, more local solidarities and forced a re-configuration of the political terrain along these freshly rigidified lines.

In fact, this act of scientific observation ushered in an obscene that was entirely new. The native logic of purity/pollution, the “scene” which could be publicly declared is now called by the colonial “civilising” eye primitive, irrational and obscene to modernity. The colonial state could thus present itself as a modernising referee, underling proving to the world that it was not some backward social order the British had themselves rendered calcified. The “native obscenity” of caste practices became the rationale for the colonial mission, just as the colonial economy frequently solidified caste-based divisions of labour.

Colonial rule did not just “disperse” (de Kiewiet’s word) the prehistoric caste “scene”; it re-staged its appearance through its interventions in western technology of knowledge, and techniques of administration and surveillance. If the previous order was premised on ritual spectacle and cosmological legitimacy, colonial modernity made caste legible as an object of bureaucratic reason. Authority was transformed from the dramatic practice of impurity to its less conspicuous, but more far-reaching, work of sorting and classifying. In Foucauldian terms, there was a substitution of sovereignty for governmentality: the village stage of hierarchy was slowly but never entirely replaced by that of archive, census table and legal code.

And enumeration was central to this transformation. Colonial census, from the end of the 19th century onwards, attempted to freeze caste identities into universal pan-Indian categories. What had been a locally contingent and regionally flexible hierarchy became interpretable to the state through lists, schedules and ethnographic description. This act of naming was not neutral. In forcing the community to map onto certain fixed classificatory grids, the colonial state both reinforced and naturalised caste. The scene was not just spatial and ritual; it had turned statistical. From the village square, visibility moved onto the bureaucratic paper. The hidden ‘obscene’ here was not just secret labour, but the insecurity and indeterminacy of everyday caste relations, just what enumeration aspired to hide.

The law additionally re-fashioned the grammar of hierarchy. Colonial law did not assimilate such norms of Dharmashastras to create “Hindu Law” but the principles selectively codified in colonial jurisprudence and statutes, transformed Brahmanical textual traditions into enforceable legal standards. But this juridification introduced an unintended ambivalence. On the one hand, it consolidated some structures of endogamy or patrimonial inheritance and, on the other hand, made possible certain space for contestation. Instead, pursuing cases in court and challenging bureaucratic rulings or attempting legal reform created new sites for subordinated groups to express grievance. Power was less visibly violent, but more extensively inscribed in institutional procedure. Foucauldian discipline supplanted sovereign terror, at the same time as older types of social coercion remained a reality.

Meanwhile, colonial political economy transformed the economic basis of caste. Monetisation, commercialisation of agriculture and a new exposure to labour mobility disrupted hereditary occupations to an extent. Emigration to plantations, railways or cities created scenarios in which ritual oversight was diluted and anonymity expanded. These spaces didn’t eliminate caste, but they broke the hermetic unity of the premodern set. Hierarchy had to be re-made in unfamiliar landscapes, creating new solidarities along with new exclusions. The obscene, once exiled from the village borders, began to seep back in through developing public forms, often in submerged or indirect ways.

Gramscian hegemony likewise underwent mutation. The karmic “common sense” which previously helped to naturalize hierarchy faced rival ideological formations: missionary critiques, liberal ideas of equality, print-mediated reform movements and pre-modern anti-caste intellectual traditions. Cosmology alone could no longer determine consent, it had to be negotiated in the languages of rights, representation and progress. But hegemony did not disappear; it was transformed. Domination groups re-articulated caste privilege through discourses of tradition, community autonomy or social order that translated ritual authority into cultural capital in the colonial public- sphere. What emerged was not rupture but re-arrangement: An older hierarchy learned to speak new idioms.

More importantly, the colonial moment created conditions for a systematic anti-caste politics. Access to education, print circulation and associational life facilitated figures like Jotirao Phule and later B.R. Ambedkar to unveil the hidden underpinning of social order. Their criticisms made visible that which had been structurally hidden for so long, the historical making of caste inequality. In Foucauldian terms, new counter-discourses challenged the regime of truth supporting hierarchy; in Gramscian terms, subaltern groups revolted for moral-intellectual hegemony. The very scene itself became a battleground not one that was divinely settled.

Colonial modernity then should be neither mistaken for sheer continuity nor for simple break. It eclipsed spectacle with surveillance, ritual fixity with bureaucratic classification and karmic inevitability with ideological contest. But that dialectic of inside-outside, the mobile frontier between scene and obscene endured in the new guise. Caste lived by infiltrating modern institutions, even as the very same institutions nurtured the forces that would eventually question its legitimacy. The oneness of the pre-modern theatre was broken, and what followed was a much more complex and unstable stage for caste drama to develop.

III. The Postcolonial Modern: Schizophrenia, Eruptions and the Hegemony of Denial

The founding of the Indian republic was a script most thrillingly re-written of the scene/obscene dialectic. Inspired by liberal democracy and led by a modernising elite, this new nation-state wanted to make a complete break with the past. And India’s public, legal “scene” was dramatically re-scripted. The framework of the Constitution, authored under B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit jurist deeply critical of caste, effectively banished it as obscene to the political-juridical order. Articles 15, 17 (which destroyed untouchability) and the guarantee of equality before the law erected a new platform that transformed individuals into citizen, rather than caste subject. The reservation policies (Articles 15(4), 16(4)) became a temporary, exceptional instrument in this stage, as corrective historical justice until achieving the final goal of “Join Casteless India”. The rhetoric of secular nationalism and, later, that of neoliberal meritocracy helped create a public sphere in which caste was meant to be sloughed off in the interests of national or consumer identity.

Caste, however, did not vanish. It had strategically migrated from the public-sacral scene to the privatised, affective, and social “obscene.” This obscene is no negative empty but a powerfully busy shadow stage. Endogamy would still be the strongest fortress. As sociologist G. Shah (2002) and others have shown, the “conjugable/unconjugable” binary flourishes in the private domain of family alliances, matrimonial ads, and community networks concealed from the law’s scrutiny. Purity/pollution practices can draw back into the private and daily life, who in principle may enter the kitchen, share a water glass, sit as an equal at a meal. These are not officially recorded, but they are vital to social reproduction. In contemporary institutions, the corporate office, the university, elite social clubs, caste operates as though it’s based on race and class, if by its own ecosystem of social capital and unspoken biases. The Dalit expert may be officially welcome on the corporate stage, but exclusion thrives in the obscene of informal circuits and cultural codes (such as hearing a last name). Anand Teltumbde (2010) calls this the “persistence of caste” in new, “camouflaged” versions in hitherto seemingly-casteless modern sites. Lynchings, social humiliations and caste-based rapes are not vestiges of a pre-modern past. They are modern obscene eruptions, as scholars such as Kalpana Kannabiran contend. They are frequently sparked, as others have also noted, by a perception of Dalits “overstepping” their bounds, owning land, riding horseback, sporting a moustache or falling in love across castes. Recorded on cell phones and disseminated through the social media, this violence is at once secret in its execution and hyper-visible in its sharing, revealing the brutal truth that the official scene seeks to deny.

The dominant casts in modern India have had a project: to naturalise the split. The new “common sense” is an aggressive discourse of the successful erasure of caste: “Caste doesn’t matter anymore,” “We are all casteless now,” “Only the backward castes talk about caste.” To talk about pervasive caste discrimination is characterised as “playing the caste card”, an obscene game of etching a primitive poison into the modern body politic. This is the hegemony that allows dominant caste persons to populate public spaces as generalised liberal individuals, free from caste bias while their social and intimate worlds are structured through caste power. It vulgarises the systemic character of caste to analysis, when it is reduced into ‘incidents’ alone or individual prejudices.

Case 1: The Khairlanji Massacre (2006): At Khairlanji town of Maharashtra wherein a Dalit family- the Bhotmanges—was lynched and women were sexually violated before they were murdered. The flash point was their testimony in a police case and the perceived social disobedience of owning property and being educated. Khairlanji is not a remnant of the archaic: it is a contemporary obscene explosion. The violence was not a spectacle of sovereign power but a secret, community-approved atrocity, later brought to light through the media and activism. It was a bid to violently re-assert a weakening local hegemony. By using the tools of modernity (courts, education, land titles), the Bhotmanges broke the “common sense” of Dalit acceptance by demanding subordination. The massacre was a demonstration to force a restoration of that “common sense.” The State’s initial reticence in using the PoA Act[1] was very much present. An alternate dialectic reveals: the progressive law (integral to constitutional scene) was subverted by the police, who were seeing it as a local arm of an obscene social order. The massive Dalit protests that followed were a counter-hegemonic gesture, dragging the obscene out of the closet and into the national eye-scape, compelling the official scene to abandon its hollow bromides and reckon with the violence it had rendered invisible.

Case 2: Corporate India and Duality of the Sabhya-Gavva: In the glass-and-steel offices of Bangalore or Gurgaon, it’s a different story. The office is a place of casteless modernity, it is run by HR (human resource) manuals and meritocratic ideology and professional dress codes. Here, caste is officially obscene; to mention it is a breach of professional etiquette. But it flourishes in the obscene of social capital (Teltumbde, 2010): weekend resorts gupshup, references and mentor chains; and crucially, ‘off-siting’ matrimonial alliances. Attempts to bring the Dalit professional into the elite corporate fold abound but they are not part of these obscene networks driving genuine career mobility and cultural identity. The hegemonic “common sense” is strong: “We don’t see caste here.” Such is the hegemony of caste, the many-layered monopoly by which privilege functions when you are a dominant caste, that it can reproduce itself updated to the gilled hilt with practised ease like no other marauding bandit – and all Dalit assertion of identity or complaint about bias can be counterpoised not as an obscenity but even better – since there’s always a reason why an obscenity cannot be effective enough in its monstrosity: casted as something that comes from ob-scoot-ated couches. This is the crowning achievement of modern caste schizophrenia: an absolute disconnection between the formal scene of liberal equality and the informal obscene of caste-reinforcing sociability.

Independence and the acceptance of a new constitution did not so much lead to the death of caste as to a transformation in the means adopted by it. If colonial modernity banished ritual spectacle in favour of bureaucratic classification, the postcolonial state ushered in a new grammar of visibility mediated by democracy, rights and representation. Caste was no longer publicly exalted in the form of sacred hierarchy; it now existed in the juridical idiom of egalitarianism and administrative calculus of reservations. The stage went from the village square and census archive to the courtroom, legislature, and electoral arena. But this transformation did not erase the old boundary of scene and obscene, it transformed it.

The explicit abjuration of untouchability and fundamental rights in the Constitution was a symbolic break with Brahmanical social ontology. In other Foucauldian terms, a new regime of truth was articulated: caste discrimination became something that it is illegal to speak about, but something that persists. That created a paradox of democratic visibility. Dalit presence in educational institutions, government bureaucracy, Parliament indicated an entry into the national scene, but leaves a lot of mediation through categories of injury, backwardness and compensatory justice. The reservation system, which is and was both re-distributive and emancipatory of caste identity, necessitated –for its operation– ongoing administrative naming of caste identity. By this, the very mechanism proposed to erode hierarchy itself re-inscribed caste within state knowledge. Visibility (to use the title of a good read) became two-edged: recognition and regulation.

This ambivalence is indicative of the larger movement from sovereign or disciplinary power toward what Foucault named bio-political administration. The post-colonial state manages its populations through welfare, quotas, development programmes and statistical surveillance. Caste in these instances is neither simply ritual nor only juridical, but becomes a demographic for techniques of governance. The obscene is no longer the occult labour that sustains ritual purity, but the residue of structural degradation that survives beneath the language of formal equality. Day-to-day violence—social boycott, atrocities, denial of access to housing or marriage networks—is frequented in a domain beyond the spectacular optics of national democracy, where it appears as exception rather than rule. What cannot be incorporated into this story of progress is relegated to the fringe of visibility.

Hegemony, as in Gramsci, thereby assumes a new form. The national promise of unity, development and democratic citizenship generates a strong ‘common sense’ that situates caste as a left-over social problem being slowly dissolved by the process of modernisation. This story line allows for some reform but overcomes more radical change. Dominant castes adjust by converting historical privilege into educational capital, bureaucratic power and management of local political establishments. Hegemony now moves away from ritual superiority to meritocratic language; inequality is no longer described using karma, but as the result of competition, culture, or efficiency. You win consent not so much by theology as by the aspirational rhetoric of the nation-state.

But the post-colonial picture is also one of an un-anticipated countervailing assertion. Dalit protests, Ambedkarite politics, literary publics and mass mobilizations turn humiliation into a collective critique. Public conversion ceremonies, acts of remembrance and symbolic appropriations of public space such as university campuses or spaces of atrocity re-perform the terrain from which Dalits were once confined. In Foucaldian parlance, subjugated knowledge systems explode into discourse questioning the neutrality of law and development. In Gramscian terms, these struggles are driven not only to inclusion but to moral-intellectual leadership capable of redefining the very order. Democracy doubles as instrument of regulation and terrain of insurgency.

This visibility is also complicated by both media and modern popular culture. Caste now whirls through television debates, digital activism, electoral rhetoric and bureaucratic documentation. The scene widens to a national and ever more virtual canvas. But growth is not the same as change. This is the realm of spectacular, and sometimes scripted, moments of outrage which can be simultaneous with banal indifference, giving rise to what could be termed a politics of intermittent visibility- caste appears dramatically in crisis and disappears back into normalcy. The obscene endures right in this several back and forth.

The postcolonial condition, then, is to be understood as a dynamic antagonism [rather than resolution]. Inherited hierarchy is contested by constitutional morality, but is also constantly re-articulated through social practice. Caste becomes subject to critique under democratic inclusion, even as administrative governance secures its categories. Power works less by oppressive and direct prohibition than by selective recognition; hegemony less by naturalised order than by promised development. It is not the distinction between scene and obscene that disappears, but rather becomes mobile, contested and historically contingent.

On this slippery ground, caste endures not as immobile tradition but as malleable entity materialised in modern institutions. Its strength is its adaptability; its weakness, the very visibility that democracy requires. The postcolonial stage then sets the stage for the contemporary moment, where neoliberal recalibration, digital moderation and new identity politics will once again realign what is visible, sayable and contestable in caste’s name.

IV. The Contemporary Neoliberal-Digital Scene: Circulation, Concealment, and Algorithmic Power

The late modern and early postmodern era represents another re-organization of caste’s scene of action, one related to neoliberal financialization, ever-faster urban transformation and digital communication. If the postcolonial constitutional order made caste visible in the languages of rights and welfare, neoliberal modernity deflects attention to markets, mobility, and privatised aspiration. Power increasingly functions by means of circulation rather than repression: capitalist, informational or affective flows transform social existence. In this terrain, caste does not vanish; it mutates, finding solace in infrastructures that seemingly are formal and neutral. The scene becomes diffuse, meshed and not entirely transparent.

Urban anonymity at first appeared to hold the promise of eroding inherited hierarchy. This was a society of skill, and with the migration to metropolitan labour markets, service economies now expanding, and meritocratic competition as the order of the business day it was implied a world governed by skill rather than by birth. But a closer look shows that caste does indeed change in response to these conditions through more subtle forms of recognition and exclusion. The segregation of housing in both the formal and informal real-estate markets, matrimonial advertisements coded by surnames and community markers, professional networks organized around kinship: All are reminders of how caste survives beneath the surface equality of contract. Free choice is, quite often, the cover for inherited social capital. In the Foucauldian sense, discipline becomes internalized as self-improvement: people structure their education, language and behaviour to mimic upper-caste cultural models. Power functions through aspiration.

This paradox of visibility and obscurity is only magnified by digital media. Social media, internet archives and digital journalism created, and continues to create, new Dalit self-presentation, memory-making and political mobilization. Stories of discrimination spread quickly and turn localised instances of pain into national or global conversations. Hashtag activism, digital memorialisation and virtual community building generate new counter-publics that challenge hegemonic narratives of caste vanishing. Subaltern knowledges gain a technological magnification, attempting to recall Foucaultian perceptions of the growth of discourse as a place for resistance.

Yet it is precisely these digital infrastructures that produce new forms of obscuration. Algorithmic sorting, datagov and platform economies all function through categories that look caste-blind even though they frequently reproduce historical inequality. Bandwidth access, linguistic capital, digital literacy, and social networks are variously unevenly distributed such that who can speak and what differences ultimately get heard is formed accordingly. Online anonymity can obscure caste identity, but it also opens the doors to a revival of abuse, harassment and symbolic violence stripped from responsibility. And so once more the obscene moves: not invisible work outside the ritual space, nor systematic humiliation under constitutional equality, but coded replication of hierarchy within seemingly neutral technological systems.

Neoliberal political economy also recasts Gramscian hegemony. Developmental nationalism is displaced by entrepreneurial individualism, with success recast in terms of personal realization rather than collective redistribution. This is an ideological shift that pulls the rug from under solidarity-based politics, while eclipsing structural constraint. Dominant caste privilege is reformulated as excellence, professionalism or global-competitiveness. Today, it is not through moral doctrine (as ideology) that hegemony functions but through desire: the desire for upward mobility within market society. Consent is obtained by promising the irrelevance of caste when in fact, material divisions remain.

Simultaneously, counter-hegemonic energies take on new shapes. Dalit entrepreneurship, trans-national mobilization, inter-sectional alliances, and cultural production in literature, film, and digital art re-invent dignity beyond the abjection of victimhood or what Geisser calls state-replaced recognition. Memory turns into political technology: archives of atrocity, commemoration of historical resistance, re-imagining Ambedkarite thought travel across geographies to confront neoliberal amnesia. These operations are not content with coming in from the outside: they want to redraw the lines of its deck, show us the hidden continuities between ritualized past and digital present.

The result is that the present period is one not of stability but rather of heightened contradiction. Caste is there and it is not; submerged in words while floating above them, crushed and dispersed in the personal but ominous in its structural totality, sundered across experience but knit tightly through data. The Foucauldian analysis shows that there is a move towards power as dispersed and infrastructural – algorithmic, not spectacular – while the Gramscian emphasises a hegemonic order built on aspiration, consumption and selective memory. The line between scene and obscene is constantly reconfigured by media circulation and political contestation.

In this neoliberal-digital formation, caste continues because it is able to occupy invisibility and exploit visibility: become visible when mobilised, disappear when asked. Its fate will rest on whether emerging counter-publics are able to change technological exposure into structure-changing possibilities, converting sporadic oppositional outcry’s to new moral-intellectual leadership. The drama of caste, far from being over, therefore moves on to a stage where power itself is more and more ethereal, and the fight to make inequality observable becomes the primary political act.

Anand Teltumbde’s analysis of caste’s “camouflaged” persistence provides a powerful lens for understanding the modern obscene. As he argues, “caste today is not what it appears to be. It has shed its religious garb and put on the secular attire of modernity” (Teltumbde 2010, 23). This insight resonates deeply with the Foucauldian scene/obscene dialectic: caste thrives precisely because it has migrated from the visible ritual scene to the hidden networks of social capital, professional networking, and matrimonial alliance. The corporate office that publicly celebrates meritocracy while privately excluding Dalits from informal mentorship networks exemplifies this schizophrenic condition. Yet Teltumbde’s Marxist commitments also remind us that this is not merely a matter of discourse or visibility: caste’s persistence is ultimately rooted in material control over land, capital, and labour. The scene/obscene dialectic, therefore, must be understood not as an alternative to materialist analysis but as a framework that reveals how power organises the visibility and invisibility of material exploitation itself.

V. Dalit Politics: Shattering the Proscenium Arch

It is possible to see the history of anti-caste resistance, from Jyotirao Phule’s radical philosophy through Ambedkarian revolutionary constitutionalism to today’s post-bahujan (radical) politics, as a prolonged struggle against this forced dialectic.

It may be noted that Dr. Ambedkar’s public burning of Manusmriti in 1927 was an archetypal act of shattering the sacred instrumentality constitutive of the old stage in scene making. In drafting the Constitution, he was seeking to reconstruct a new, fair scene from below. Dalit political and cultural assertion is, at bottom, a way of calling the obscene into the eye of the scene. The Bahujan political parties (such as the BSP party) emerging to prominence have put caste identity, previously considered a shame marker, on the national stage of the electoral politics for a source of pride and community mobilization. The taking of public space, a public scene which performs the exhibitionism of “dalitness” could be interpreted by authorities as a sign that dalits are trying to create some kind of counter-public space. The “cattle meet festival” is striking in this regard, by publicly eating the meat deemed most polluting within Brahminical norms, activists force the unspeakable into public space, undermining the grammar of purity/pollution itself.

Dalit Studies, as it is being launched by veteran scholars such as Gopal Guru and others, does this important labour of theorising from the site of the obscene. It confronts the hegemonic “common sense” with a systematic recording and analysis of the lived experience of caste, not leaving it as anecdotal or passé.

VI. Synthesis and Conclusion: The Dialectic’s Enduring Grip and Its Cracks

The Foucauldian Gramscian analysis discovers that caste-modernity is not to be located in its end, but rather its strategic disintegration. Power circulates by keeping intact the gap between disavowing public scene and luminous private torque. The state’s role turns Janus-faced: progressive legislation that has made lives more livable and breathable in some ways, but that has also all too frequently, through institutional bias and political compromise, proved itself powerless to prevent obscene eruptions of violence.

This arrangement suits liberal democracy down to the ground, for it provides protection for the “private” sphere as an area beyond state interference and lets caste flourish there behind a screen of personal choice and cultural preference. It is also conducive to global capitalism, which can use caste-based social networks to control labour even as it floats a veneer of meritocratic neutrality.

But the dialectic is also an inherently unstable one. Every Khairlanji that turns into an issue of national interest, every corporate diversity report that whispers exclusion, every inter-caste marriage that invites ridicule is also a moment of rupture. In its varied avatars, it is Dalit politics that remains the sustained force challenging this division. The last struggle, as Ambedkar hoped, is not one for entry into the existing scene so much as to destroy the double stage itself, to establish a social order where the caste-based history and present are not some dirty secrets but an openly avowed basis for a common sense that is genuinely universalist and egalitarian. So long as that dialectic exists, caste in its morphed and schizophrenic form continues to survive.

(Note-An earlier version of this paper has appeared on SSRN E-Library, Elsevier.)

(The author teaches history at Shivaji College, University of Delhi. He can be reached at skandpriya@shivaji.du.ac.in)

References

Cohn, Bernard S. Colonialism and Its Forms of Knowledge. Princeton University Press, 1996.

Dirks, Nicholas B. Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Princeton University Press, 2001.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Vintage, 1977.

Gramsci, Antonio. Selections from the Prison Notebooks. International Publishers, 1971.

Guru, Gopal. Humiliation: Claims and Context. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Guru, Gopal, and Sundar Sarukkai. The Cracked Mirror: An Indian Debate on Experience and Theory. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Pandian, M.S.S. Brahmin & Non-Brahmin: Genealogies of the Tamil Political Present. Permanent Black, 2007.

Rao, Anupama. The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India. University of California Press, 2009.

Rege, Sharmila. Writing Caste/Writing Gender: Narrating Dalit Women’s Testimonios. Zubaan, 2006.

Risley, H.H. (Sir). Census of India, 1901. Vol. I, India. Part I, Report. Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, India, 1903.

Teltumbde, Anand. The Persistence of Caste: The Khairlanji Murders and India’s Hidden Apartheid. Zed Books, 2010.

The Smritichandrika of Devanna Bhatta (Trans. J.R. Gharpure). 1948.

South Indian Inscriptions (Vol. III, Chola Inscriptions). Archaeological Survey of India.

[1] Prevention of Atrocities Act (1989)

Related:

The Anatomy of Humiliation: Defining caste violence in the Constitutional era

Caste and community creations of human beings, God is always neutral: Madras HC