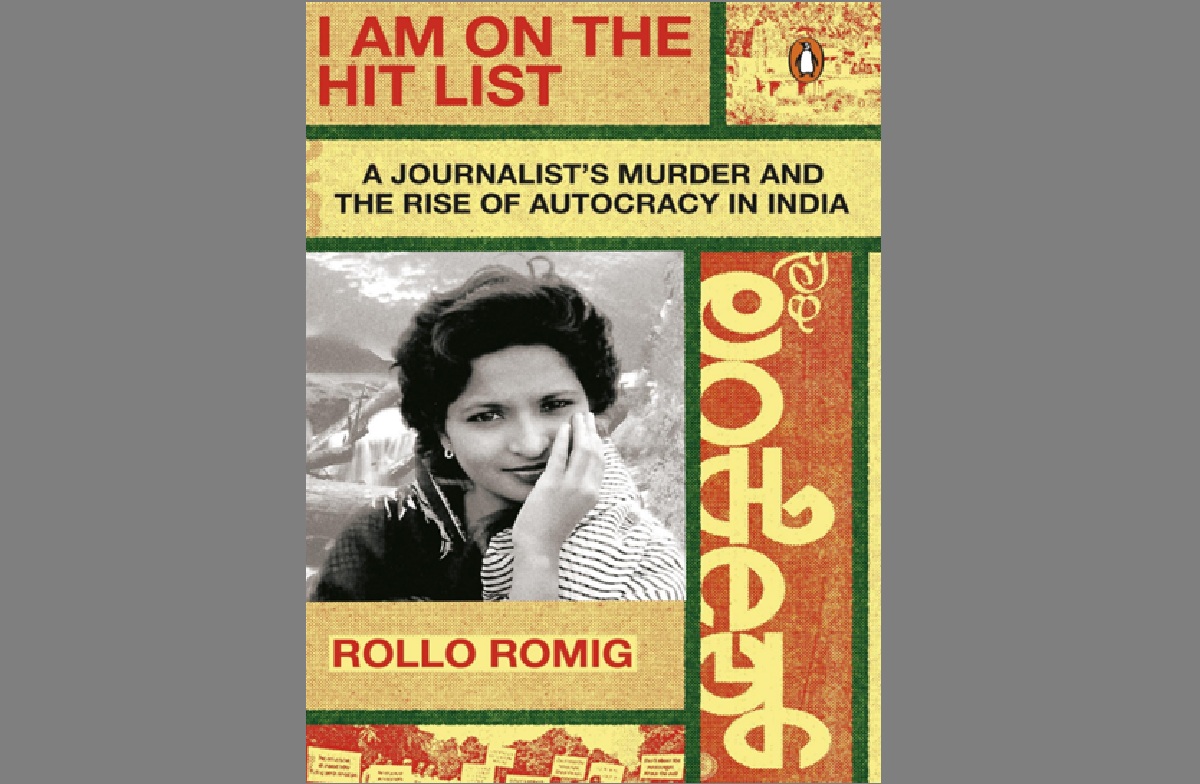

Last year, in 2024, Rollo Romig, an American journalist who lived in Bengaluru (Bangalore) and knew Gauri Lankesh, published the much acclaimed book I am on the Hit List, an investigation into the circumstances around her brute killing and on the broader socio-political environment in the state of Karnataka and country. Published by Penguin Books in 2024, the Indian edition has been published by Westland Books for distribution in India.

The book which has been widely reviewed including by the New York Times, Publisher’s Weekly, Kirkus and Tribune India was also a 2025 Pulitzer Prize Finalist for General Nonfiction. The Pulitzer Board called it “a captivating account of a crusading South Indian’s murder, a mystery rich in local culture and politics that also connects to such global themes as authoritarianism, fundamentalism and other threats to free expression.” Sabrangindia is grateful for permission from the authors and publishers to publish four excerpts, at intervals of the book.

The characteristic spunk that epitomized Gauri Lankesh, was evident in the courageous move she made for English to Kannada writing, taking over the mantle of Editor of the iconic Lankesh Patrike, on her father, Parvathi Lankesh’s demise. Her spoken and written Kannada at the time was sketchy and defying the rather patronizing advice of her then colleagues in the weekly, she jumped right in, penning editorials at the start in what the author describes as “clunky Kannada.” It was her editorship of this weekly that later morphed into Gauri Lankesh Patrike that radicalized her, and transformed her into an activist journalist. This chapter from the book also deals with her close involvement with the syncretic Baba Budangiri (Boudhangiri) movement in the early 2000s that preceded the Gujarat pogrom of 2002.

CHAPTER 11

The Ayodhya of the South

It was not long after Sreedhar launched Agni that Lankesh died and Gauri became editor of his paper. Lankesh Patrike didn’t miss a week. Its first issue under Gauri was a tribute to her father. And then the exodus began. Many of the paper’s staffers and writers were there solely for Lankesh, and with Lankesh gone, they quickly left, too. Yet she took the helm of the paper with surprising confidence. Early on she placed a phone call to Chandre Gowda, who wrote a weekly humour column for her father’s Lankesh Patrike, to discuss his further contributions. When he asked who was calling, she said, “It’s me, your mother.” He was so impressed by her openness and pluck that he took her to meet his extended family in their rural villages. “She was very innocent, just like a child,” he wrote. “She would not mind going anywhere, meeting anyone and dining with anyone.” On one such visit, Gauri’s drinking and smoking scandalized Gowda’s neighbours. But his aunt was as impressed as he was. “If we have daughters like this, what do we want sons for?” she said. He was the only Lankesh-era writer who stayed with her to the end, writing his column until her very last issue.

Other Lankesh loyalists were repelled by her show of, as they saw it, unearned arrogance and stubbornness. “We did snigger at her,” Pratibha Nandakumar recalls. Within nine months nearly every staffer and writer who’d worked for Lankesh had quit. Circulation plummeted. Longtime readers complained, according to one writer, that “Lankesh’s tabloid has become as weak as his weak-looking daughter.”

The biggest complaint with Gauri’s leadership was that she was barely literate in Kannada, the language of the paper. How could she edit a paper that, in many readers’ minds, had captured that language’s essence? Her entire education had been in English; at her elementary school in Basavanagudi, students were scolded if they spoke in Kannada. In college she failed her Kannada exams twice in a row, and disuse had eroded her skills from there. When she was away from Bangalore, her letters home to her parents were in English. The Times of India’s Bangalore bureau had hired her on the assumption that she, as the daughter of a genius of Kannada, would at least be able to read press releases in the language. She bluffed her way through, passing off the task to a Kannada-fluent colleague. One editor made the mistake of assigning her to cover the World Kannada Conference in Mysore. The speakers’ words “simply flew over my head,” she later wrote.

But as the new editor of Lankesh Patrike, she stopped trying to bluff. Thirty-eight years old, she resolved that she would conquer Kannada once and for all, and she met that resolution with impressive speed. Her new colleagues suggested that, at least at first, she could write her editorials in English, and they’d translate for her. But she refused, and wrote in her clunky Kannada from the very first issue. Within a couple years, she’d improved enough to catch errors that the proof-reader had missed. She took to heart her father’s philosophy that you’ll reach your readers best if you write simply, honestly, and unpretentiously. She’d always been stronger in spoken Kannada, so she wrote as she spoke, colloquially, Rajghatta writes, “in free- flowing street Kannada.”

She was unfailingly frank about her Kannada deficit. “There are several problems in my Kannada even now,” she wrote (in Kannada) in 2013. “Lacking a rich Kannada vocabulary is a major weakness.” Some jeered anyway at her Kannada, and also for how little she knew of her father’s work. She venerated her father, yet at the time of his death she’d read very little of his writing, because so little had been translated into English. She made a crash course of this, too, immersing herself in his columns, a project that revealed to her at last what made his paper so special and deepened her understanding and appreciation of Karnataka and Kannada culture.

- • •

IN AN INTERVIEW IN March 2000—two months after she took over Lankesh Patrike—Gauri was asked bluntly about her new job: “Your critics point out that your career graph has been far from spectacular, and that for the past decade your career has been either stagnating or going downhill. Do you think this was a lucky break for you?” Gauri answered, “I would be the first person to admit that my career was stagnating like nobody’s business. Perhaps it was because I did not want to take risks. Maybe it was because my personal life has not exactly been terrific. I was concentrating more on finding personal happiness than on chasing a career. Today, I am happy with myself, and don’t mind whatever price I have had to pay for it.”

The interviewer asked if she felt able to withstand the threats and insults that any tabloid editor is subject to. “I think being a woman is quite useful in this situation,” Gauri said, “because if any of our reporters met a politician who was angry with my father, the politician would use the foulest language against my father. But if they badmouth a woman, they will lose respect and face in the society themselves! So being a woman is my security right now.”

“Your being a woman may not dissuade them from attacking you physically,” the interviewer replied. “They will know you are particularly vulnerable as you are single and living alone.”

Gauri dismissed it: “I am not afraid of physical attacks at all.”

It didn’t take long for her to kick up controversy. After she published an investigative report on eight powerful Hindu mathas, or monasteries, in the coastal Karnataka city of Udupi, right-wing activists of the Sangh Parivar responded with fury, seizing copies of Lankesh Patrike from newsstands by force and setting them on fire. At an angry rally in a city square, the activists threatened Gauri and her writers as police looked on and took no action.

Like her father, Gauri didn’t hesitate to insult the paper’s friends or even its contributors. The writer Rahamat Tarikere recalls that Gauri had invited him to review a book for the paper. But before he had a chance to do so, a reporter for the paper asked him to comment on a campaign by some Muslim fundamentalists against a fellow member of the Muslim Progressive Writers Forum. Tarikere was slow to respond, so the Lankesh Patrike writer denounced him, in print, as a fundamentalist. He wrote for the paper anyway. Gauri was “blunt, rash, and obstinate,” he wrote after her death. But these qualities, he thought, were balanced by her “simplicity, humaneness, and commitment.”

Lankesh’s legacy loomed over her editorship. She refused to sit at his desk or in his chair; she put her own desk next to his and maintained it like a shrine. Like her father’s, Gauri’s version of Lankesh Patrike accepted no advertisements, mocked the powerful with belittling nicknames, sided unvaryingly with the oppressed, and deplored euphemisms of any kind. But Gauri mostly jettisoned the paper’s literary side. “She had no sense of literature, actually,” her friend Vivek Shanbhag, the novelist, said with a laugh. “Nor did she have people who could help her with that in her paper. So nobody looked to Lankesh Patrike to read a story or a review. That aspect was completely gone.”

More than anything, her friends said, editing the paper radicalized her. After spending much of her adult life removed from Karnataka, she suddenly found herself immersed in its problems: the labour complaints of Bangalore’s municipal sanitation workers, or the persistence of disturbingly retrograde local superstitions such as made snana, wherein “low” caste Hindus roll on the ground over leftover food from a ceremonial meal eaten by Brahmins. (The practice was finally outlawed in Karnataka in 2017.) She took on causes, too, that her father hadn’t concerned himself with, in part by learning from her mistakes. Early in her tenure, one of her reporters wrote a story that was casually derogatory toward transgender people, and Gauri published it. Members of the transgender community sued the paper, and her lawyer, B. T. Venkatesh, took Gauri to meet with them. She came away from the encounter a full-throated defender of their cause forever after. “She was the first woman journalist to support sexual minorities’ movement,” wrote the Bangalore-based transgender activist Akkai. Gauri later published a Kannada translation of the memoirs of the Trans activist A. Revathi and often covered LGBTQ struggles in the paper. The Trans community called her akka, or elder sister. When she died, they were at the forefront of fundraising for the protests in response to her murder.

At first, Gauri held on to traditional ideas of journalistic neutrality. After two decades of inculcation by journalism schools and mainstream-media jobs, she felt that journalism and activism were two realms best kept distinct. Her awakening to activist journalism came on a mountaintop 170 miles west of Bangalore.

- • •

HIGH ON A MOUNTAIN RANGE called Baba Budangiri, in central Karnataka’s Chikmagalur district, there is a shrine in a small cave shrouded by clouds. The mountains are named for Baba Budan, a Muslim Sufi saint who once lived in the shrine. According to one legend, on his return home from taking the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, Baba Budan exited the Arabian Peninsula with seven raw coffee beans smuggled in his beard, thereby evading the strict export controls that allowed the Arabs to maintain a monopoly on coffee cultivation. Baba Budan planted the beans at home and introduced India to the delights of coffee. But there are so many legends surrounding this cave that it’s impossible to reduce the place to any single uncontradictory spiritual narrative. Some Muslims believe that the shrine began as the home of a direct disciple of Muhammad’s named Hazrat Dada Hayath Meer Khalandar; some Hindus call that same person Dattatreya and believe he was a combined avatar of all three of the paramount gods of Hinduism: Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu. For centuries, Dada versus Dattatreya wasn’t a debate; the blended legends only enhanced the site’s power for Hindus and Muslims alike.

Inside its tight, dank confines, the cave is crowded with markers of both religions: at one end, several Sufi tombs; at another, a Hindu idol draped with flowers and slathered with mud. The presiding priest is a Muslim who performs traditionally Hindu rituals: lighting the oil lamp, offering puja, blessing each visitor with holy water. The shrine’s official name is Sri Guru Dattatreya Bababudan Swamy Dargah—an amazing mash-up of Hindu and Muslim names and terms.

Hinduism and Islam might look on paper like stark and irreconcilable opposites, but the kind of fusion observable at Baba Budangiri has long been commonplace across India. In Bengal there was Satya Pir, a Muslim holy man who’s also thought to be an avatar of Vishnu. In Varanasi there was the beloved mystic poet Kabir, whose critiques of both Hinduism and Islam led him to a faith that borrowed from both. In Punjab, Guru Nanak, the founder of the Sikh religion, also took inspiration from both Hindu scriptures and the Quran. But perhaps more than any other region in India, Karnataka proliferates in syncretic sites like Baba Budangiri, where Islam and Hinduism don’t just coexist but converge.

So much of the unique beauty of Hinduism throughout its long history flows from its open-mindedness, its dazzling diversity in practice and devotion and interpretation across the subcontinent. Swami Vivekananda famously declared that Hinduism recognizes all religions as true. Once, when referred to as a Hindu, Mohandas Gandhi said, “I am a Hindu, a Muslim, a Christian, a Parsi, a Jew”; Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the future founder of Pakistan, cracked in response, “Only a Hindu could say that.”

The religion we call Hinduism is extraordinarily multifarious, especially from region to region. In fact, “Hindu” originated as an outsider’s word for Indians that became, under the British, a colonial umbrella term for all the countless non-Abrahamic religious practices, philosophical traditions, and spiritual affiliations of the Indian subcontinent. The idea that there is a religion called “Hinduism” emerged from a foreign occupier’s attempt, out of fear and confusion, to simplify and codify an impossibly diverse constellation of faiths in the subcontinent, to force a Western religious structure onto a spiritual paradigm whose very specialness derives from its complexity and decentralized multiplicity. Unlike any other religion, it has always been wonderfully difficult even to define what Hinduism is in any universally satisfactory way. You can’t call it polytheistic, because there are monotheistic and even atheistic Hindus. There is not a single tenet that all Hindus must believe to be Hindu, nor a single rite that all must perform. This is not to say that Hinduism is at all vague or noncommittal, like a sort of South Asian Unitarian Universalism, but simply that it’s never uniform. At a certain point you just have to surrender to a (fittingly) circular definition: Hinduism is the religion that Hindus practice.

Syncretic sites like Baba Budangiri are the religion’s frontiers, where its porousness is most tangible. In any religion, the policing of such sites is the surest sign of a hard shift toward orthodoxy—toward an attempt to rigidly define. On most days, Baba Budangiri still appears to be quite harmonious. In fact, it’s become the most hotly contested syncretic site in all of Karnataka and the central rallying point for the state’s Hindutva groups. To them, syncretism itself is intolerable, and they chose Baba Budangiri to make an example of.

The trouble began around 1984, when Hindutva activists first organized an event on Baba Budangiri that became a large, festive, and increasingly hostile yearly rally called Dattatreya Jayanti. Soon they were referring to this newly coined practice as a long-held tradition. In the mid-1990s, a time of surging Hindutva activism, the Dattatreya Jayanti expanded and became rowdier, replete with demands to “liberate” the cave from “Muslim control” and vilifications of its Muslim caretaker. Sangh Parivar and BJP leaders in Karnataka began talking about making Baba Budangiri “the Ayodhya of the South.”

The Sangh Parivar had learned in Ayodhya that inflaming communal tensions (or even inventing them outright) was a winning electoral and ideological strategy. The BJP had been looking for a foothold in Karnataka, which it considered its “gateway to the South,” so it was natural that it would seek out a site in which it could provoke interreligious conflict. Baba Budangiri seemed just the place. And the BJP has benefited enormously. Several of Karnataka’s current BJP leaders made their names as Hindutva activists at Baba Budangiri, and the BJP came to dominate Chikmagalur district, which prior to the conflict had long been a Congress Party stronghold.

In the 1990s, Hindutva activists repeatedly attempted to install in the shrine Hindu idols that had previously never been a part of the place, despite a Supreme Court order, issued in light of the agitations, that prohibited all practices at the shrine that did not exist prior to June 1975. (Police took no action in response to any violation of this order.) Led by Sangh Parivar organizations and by the Karnataka-based fringe group Sri Ram Sena, Hindutva activists increasingly vandalized Muslim homes, vehicles, and shops in the area. In 1999, a prominent BJP politician threatened to deploy “suicide squads” to liberate the shrine.

Progressive Kannadigas were increasingly alarmed. A consortium of secular activist organizations called the Bababudangiri Harmony Forum formed to counteract the Hindutva activists, and in October 2001 they asked some local literary celebrities to issue a press statement drawing attention to the worsening climate at the mountain shrine. The first person they asked was Girish Karnad, who immediately agreed and one-upped them: Why don’t we all visit the shrine on a fact-finding mission and hold a press conference there? And he suggested another writer to invite along: Gauri Lankesh. He’d thought of her, he admitted to me, not for her platform or because she was particularly engaged in the issue but simply because he didn’t want the delegation to be entirely male.

Her first impulse was to decline. At that point she’d been editing Lankesh Patrike for nearly two years, and she was so consumed by the work that she felt she couldn’t spare the time. But then, in an impulsive decision that would reroute her life, she changed her mind, and they made the journey up to Baba Budangiri that very day.

When they reached the shrine, Gauri was profoundly moved by its merger of Hindu and Muslim practices. It was a place, she said later, that “uplifts the blueprint of secularism laid out in our constitution. It is a symbol of that very idea.” Likewise, the activists of the Bababudangiri Harmony Forum were impressed by Gauri’s energy and good humor. She’d found her people. It was atop that mountain that she began her transition from “objective” journalist to activist-journalist. “That’s where she flowered,” Girish Karnad told me. “That was the beginning of Gauri Lankesh’s career.” When they came back downhill, Gauri assumed the lead of the delegation’s response. “She handled the press. She called the chief minister and said why don’t you meet us,” one of the Harmony Forum organizers told me. “I wouldn’t have had the guts to ring the chief minister and ask for a meeting, but she did.”

- • •

JUST A FEW MONTHS after Gauri’s first visit to Baba Budangiri came the Gujarat pogrom of 2002. The unchecked violence left Indian Muslims and progressives like Gauri deeply shaken.

India’s 200 million Muslims, who represent approximately 14 percent of India’s total population, are the world’s largest religious minority. There are roughly as many Muslims in India as in Pakistan; Indonesia is the only country in the world with a larger Muslim population. For the past century, Hindutva activists have complained that India, and the Congress Party in particular, has given Indian Muslims preferential treatment—that they are being “appeased.” But by many measures, Muslims are India’s most oppressed minority. In most states Muslims earn on average even less than Dalits. The proportion of Muslims in prestigious positions is far below their proportion in the general population; that’s true in the civil services, the judiciary, the legislature, the universities, and white-collar professions. Muslims are severely underrepresented among government employees, and those who are hired overwhelmingly work at the lowest levels. The numbers are especially stark in the military and intelligence branches, which seem to find India’s Muslims collectively suspicious. Only 2 percent of India’s military is Muslim. There has never been a Muslim officer of the Research and Analysis Wing, the Indian equivalent of the CIA, since its founding in 1968.

Muslim political representation is almost non-existent. No state has a Muslim chief minister, and no Muslim chief minister outside Jammu and Kashmir has ever completed a full term. “Low” caste Hindus have a proportion of reserved legislative seats to counteract discrimination against them; Muslims have none. In 2022, the BJP became the first ruling party in Indian history with not a single Muslim legislator in its ranks: none in the upper house of Parliament, none in the lower house, none in any state. And because the Congress Party fears the BJP accusation that it appeases Muslims, Congress, too, now seldom runs Muslim candidates and rarely even refers to Muslims and their particular problems.

One of those problems is forced ghettoization. Its long been nearly impossible for a Muslim to rent an apartment in many Indian urban neighborhoods. The ghetto neighborhoods Muslims are pushed into are neglected by municipal authorities and tend to lack basic facilities: clean water, schools, parks. Much like the redlining of Black neighborhoods in the United States, Indian banks have been found to mark Muslim neighborhoods as “negative geographical zones” where loans are discouraged. Muslims who live in predominantly Hindu neighborhoods often suffer the most in episodes of religious violence; the aim of a pogrom is to ethnically cleanse. But when Muslims then retreat to the relative safety of a ghetto, Hindutva complains about their aloofness. “Wherever Muslims live, they don’t like to live in co-existence with others, they don’t like to mingle with others,” the BJP Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee said on April 12, 2002— immediately after the Gujarat pogrom.

To Hindutva, Muslims are always one undifferentiated mass, collectively guilty for whatever transgression, real or imagined, that any member of their faith is supposed to have committed, either in the present or in centuries in the past. There are three associations that Hindutva insists on applying to Indian Muslims: the Mughals, Pakistan, and terrorism. Historically speaking, Hindutva has a particular obsession with the Mughals, the Muslim empire that made its first conquest in India in 1526 and rapidly declined after 1707. (They never entirely controlled South India.) In the Hindutva worldview, the Mughals robbed Hindus of a mythical golden age. Hindutva leaders, Modi included, often complain of the centuries of “servitude” that India endured under the Mughals, and heavily imply that contemporary Indian Muslims, by extension, are no better than foreign invaders. The Hindutva version of Mughal history relies heavily on texts authored by the colonial British, who exaggerated the Mughals’ brutality and foreignness so that they could present themselves as liberators. The real history is much more complicated, but it’s irrelevant to how Indian Muslims are treated now.

As for Pakistan, Hindutva assumes that all Muslims are fifth columnists with secret loyalty to the nation’s most hated enemy, traitors unless proven otherwise. “It would be suicidal to delude ourselves into believing that they have turned patriots overnight after the creation of Pakistan,” the Hindutva ideologue M. S. Golwalkar wrote in his most popular book. “On the contrary, the Muslim menace has increased a hundredfold.” In fact, India’s large Muslim population owes itself to the fact that at partition, so many millions of Indian Muslims actively decided against Muslim Pakistan in favour of pluralist India. According to the Hindutva narrative, Indian Muslims spend most of their time plotting to bring down the nation and applauding the Pakistani cricket team. In my own experience, Indian Muslims are much more likely to be busy forwarding goofy Bollywood memes on WhatsApp, like any other Indian. Hindutva wants to paint all Indian Muslims as ignorant fundamentalists and to erase all Muslim contributions to Indian life: not just syncretic sites like Baba Budangiri but also the Taj Mahal, and Muslim movie stars, and the entirety of Urdu culture, with all the exquisite sophistication of its poetry, its music, its manners.

Hindutva activists and politicians often use the word “terrorists” as a synonym for Indian Muslims. There have undoubtedly been horrifying terrorist attacks committed by Muslims on Indian soil (although some of the worst attacks originated from Pakistan). But the threat and scale of terrorism is always, almost by definition, wildly exaggerated. The number of Indians killed in terror attacks is a minuscule fraction of those killed in pogroms, which the terror attacks are typically staged in response to—which is not at all to excuse them but simply to put them in context. And as should be too obvious to say, only an infinitesimal number of Muslims, Indian or Pakistani, have anything to do with terrorism. It’s a wretched cycle: Hindutva tries to force Muslims, already a beleaguered minority, into total submission, and a tiny number of Muslims reacts with impotent and self-defeating acts of sensational violence, which only feeds the Hindutva argument that Muslims need to be forced into submission. Since 2008, the number of terror attacks perpetrated in India by Muslims has sharply declined. But such is the nature of terror attacks that the fear of them lingers long, especially when politicians keep whipping it up.

As soon as Modi took office in 2014, the position of Indian Muslims became palpably more precarious. Lynch mobs murdered scores of Muslims suspected of slaughtering or selling cattle, in supposed defence of the cow as a sacred animal. In 2015, after one of the most notorious of such lynchings, in which a man was slaughtered in his home by neighbours who suspected, inaccurately, that he was storing beef, a BJP politician offered the murderers jobs, and a BJP chief minister invited them to a party rally. In 2018, a Modi cabinet minister garlanded and fed sweets to eight men who’d been convicted of murdering a Muslim meat trader. Modi didn’t say a word about the lynchings for over two years.

- • •

THE VIOLENCE IN GUJARAT pushed Gauri to intensify her involvement at Baba Budangiri, the communal flash point in her own backyard. It was through her enthusiastic adoption of that cause that she met for the first time, in 2002, her loyal friend Shivasundar, who would soon become her closest colleague in her journalism and in her activism. Shivasundar had long experience as an activist, but Gauri was green. “She came across as concerned but very urban educated, a little arrogant, a little dismissive about the kind of activism on the street,” he recalled. But something about Baba Budangiri struck her irrevocably, and she applied herself to the problem with the zeal of a convert. Soon she was not simply reporting on the news from Baba Budangiri but making news, headlining counterdemonstrations, using her office as a protest-planning hub.

“It is no secret that the monkeys of the Bajrang Dal are gearing up to create disruptions at Bababudangiri this year,” Gauri wrote in late 2003, about one of the most aggressive RSS affiliates. Hindutva activists had been hoisting banners at the shrine with threatening phrases: “muscle power,” “streams of blood,” “destroy the enemy.” The atmosphere had grown so heated that the state government banned outdoor gatherings in Chikmagalur, the city nearest to the shrine, in an attempt to prevent mass protests. Gauri was determined to go anyway, and on the way up the mountain she and another activist with the Harmony Forum, an English professor named V. S. Sreedhara, spontaneously got out of the car they were in and hitched a ride in a truck to enter town less conspicuously. “It was a very filmy romantic escapade,” Sreedhara told me. “She said it was like we were eloping. Even in those tense moments she would joke like that.”

Gauri sneaked into town wearing a burqa, then threw it off outside the police station and shouted slogans until she was hauled into custody. Hundreds of other activists were also arrested, and they walked into jail singing anthems in unison. They spent two days massed together in the city’s newly constructed jail. “We inaugurated it,” Shivasundar said with a mischievous grin. They slept on the floor, and drinking water, when it finally arrived, was provided by the jailer in garbage barrels. “But none of these difficulties hurt our confidence or lessened our zeal,” Gauri wrote. “On the contrary, the two days brought us closer together, inspired us to keep up the fight and nourished our spirits…. The jail was indeed like a microcosm of Karnataka. It had young boys and girls, progressive thinkers, communists, Muslim community leaders, artists, journalists, teachers, women activists, farmers’ leaders and politicians from across Karnataka.” Even a handful of Bajrang Dal activists were accidentally arrested along with them. “It looked like they were complete converts to the cause of social harmony after the two-day stay with us,” she wrote. The new issue of Lankesh Patrike had to go to print the night the group was arrested, so she dictated her column from the jail by mobile phone.

While the communal-harmony activists sat in jail, the Hindutva activists held a huge rally, unbothered by the police, and their speeches targeted Gauri and Girish Karnad above all. “Gauri!” crowed Pramod Muthalik, leader of the Sri Ram Sena, as the crowd jeered. “Respected Gauri Lankesh! The police should have left you free. Had they not arrested her, she would have learned the true meaning of harmony. She would have been stripped stark naked and made to stand on top of that hill!”

Among those arrested with Gauri was Agni Sreedhar, the ex-don, whose tabloid Agni was then in its fifth year. He and Gauri had become rival editors, and they’d sometimes make snide oblique remarks about each other in their editorials—especially Gauri, who disdained Sreedhar’s gangster past and scoffed at the idea that he’d reformed. But politically they were largely aligned, especially when it came to promoting communal harmony and opposing the ascendant right wing. (I found a photo of Sreedhar protesting a visit Narendra Modi made to Bangalore in 2013, the year before he was elected prime minister; Sreedhar was holding a sign that read: modi hitler, uo back, uo back.)

Some weeks after their stint in jail, the harmony activists were finally permitted to stage their own mass rally; Sreedhar and Gauri shared the stage. Sreedhar told me very proudly about the speech he gave, in which, as he often does, he leveraged his gangster reputation for dramatic effect. “Now we have only one option,” he told the crowd, which, as he recalls, numbered ten or twenty thousand. “We have to break heads. Are you ready?” The crowd, he said, “became frenzied,” and he kept whipping them up until finally delivering the punch line: “Now I’ll tell you the target: you have to break open your own head.” Then he chastised them for buying into his parody of inflammatory rhetoric. “You were ready to break open someone else’s head. But you’re not ready to open your own mind.”

Building on their growing solidarity after the mass arrest of 2003, secular organizers launched an even larger umbrella group of like-minded activists called the Karnataka Communal Harmony Forum, aimed at easing religious conflict and tackling bigotry wherever they arose in the state. Its membership was a roll call of Karnataka’s progressives. Gauri’s Lankesh Patrike became one of the movement’s most eager platforms.

For all her passionate commitment to communal harmony and angry opposition to bigotry against Muslims, Gauri was never an apologist for conservative Islam. Once a Muslim organization invited her to speak at a large meeting on human rights, and she was miffed when she realized she was the only woman in attendance. Next time, she told the crowd directly, if you don’t bring women in, I won’t come. And from then on the organization included Muslim women in their meetings, too. Prayer baffled her. One activist colleague remembers that when they were arrested on the way to Baba Budangiri, several Muslims were jailed with them, and Gauri was dumbstruck when they got up early to observe the dawn prayer. “She burst out laughing, saying, ‘We are in prison. I can’t understand this religiosity.’ ”

All the same, Gauri once personally translated into Kannada and published a classic text of Sufi Islam: Idries Shah’s Tales of the Dervishes. I asked her friend Mamta Sagar why she might have done so. “It’s easy for us to create the Other out of Muslims because we don’t give them space to say anything,” she said. The void is filled, she said, with a steady patter of negative comments about Muslims: that they’re dirty, they’re violent, they hate Hindus. Gauri was dismayed when one of the greatest Kannada novelists, S. L. Bhyrappa, started writing overtly anti-Muslim novels that became bestsellers. In this context, Sagar said, “bringing in more Islamic references which are positive is important. Maybe that’s why she did it.”

Beginning with Baba Budangiri, the local defense of Indian pluralism became Gauri’s signature cause. “The arrest made her a kind of celebrity,” one activist told me. “From then on she was in demand—every forum, whatever little cause they were fighting, they invited her and she managed to go.” She’d always been opinionated, but it was Baba Budangiri that radicalized her into an unequivocal leftist—even if her brand of leftism always remained a bit vague—and an unabashed activist, positions that she immediately reflected in the pages of Lankesh Patrike. She liked to say that she had three children: her niece Esha, her newspaper, and the Communal Harmony Forum.

(Parts two, three and four of more excerpts from the book to be also published at intervals)

Note from the Editors: We would like to express our heartfelt solidarity with the family of Gauri Lankesh, Indira Lankesh, Kavitha and Esha Laneksh, who have with pathos and determination built on the gaping vacuum created by Gauri Lankesh’s assassination. Gauri was also a close a dear activist friend of Sabrangindia’s co-editor, Teesta Setalvad.

Related:

Storms battered her from outside, but she stood, an unwavering flame: Gauri Lankesh

Gauri Lankesh assassination: 6 years down, no closure for family and friends, justice elusive