The Minister of External Affairs S. Jaishankar recently gave a talk at University College Dublin (UCD) in Ireland as part of his UK and Ireland tour. This was the first visit by an Indian minister to Ireland since 2015. I happen to study at UCD and ended up attending the event, curious as to why he’d chosen our rather obscure university to speak at.

Outside the auditorium, a long queue assembled in the lobby of the O’Brien Science Building. Most of them were Indian students. Eventually, I began conversing with the person ahead of me and we found seats together. He was in his late twenties, doing his masters, and had previously worked at a large e-commerce MNC (multi-national company) before moving to Ireland. I asked him why he was attending today’s talk by the foreign minister. He said that he was a big admirer of Dr. S. Jaishankar and his work, as well as ‘other leaders’ like him.

According to him, Dr. Jaishankar was a ‘smart’ and ‘bold’ person who cared for the country’s interests and how Indians were represented abroad. Challenging his point, I brought up the recent deportations of illegal Indian immigrants from the United States and the minister’s tepid response to the matter. He replied saying the immigrants had committed a crime by being in the States illegally and therefore it was right they were sent back. ‘In chains?’ I added. No, he said. ‘That went too far. But America will be America.’

As for those ‘other leaders’ he said, ‘the thing I like about this government is that they put the country first. The country comes first and then everything else.’ I found this interesting. By putting the country first, he was referring to the government’s unwavering focus on growth and development. I said that not all Indians saw this growth. In fact, most Indians still suffered gruelling poverty, malnutrition, and unemployment. Becoming aware of my political outlook and wanting to avoid further argument, he finally said, ‘everyone has their opinions. And everyone’s opinion matters.’

Meanwhile, the auditorium filled to its capacity. The students were visibly excited to see the Foreign Minister. Observing them, I became aware of the possibility that many students here may share my friend’s views. Since coming to Ireland, I’ve had mixed feelings encountering large groups of Indians. Many of them expect you to speak in Hindi, even in a foreign land, which as a South Indian I am not eager to oblige. Then there’s a cautionary feeling; one that comes with being a minority in India. I first gauge the political leanings of the people I interact with, some of whom under the guise of being ‘non-political’, defer in favour of the ruling party.

Here in Ireland, I am far away from the religious violence at home. Yet I find it strange carrying on conversations with supporters of the ruling party, pretending their views shouldn’t affect the pleasure of their company.

Why beat around the bush? I thought. I asked him frankly what he thought about the divisive politics of the government — the remaking of India as a Hindu nation, and the rise of hate speech and violence against Christians and Muslims. In response, he said that every government had its own variety of politics. Hindu-Muslim was just the ruling party’s version of it. In the end it was about winning elections, in other words — power. I was oddly relieved to hear this answer. It seemed analysed from a neutral but nevertheless, ruthlessly pragmatic standpoint.

‘But,’ he continued. ‘There must be a balance of power. Hindus have nowhere else to go in this world. What if something were to happen to us? There must be mutual respect. We respect all religions. But they should also respect us.’ By ‘they’ he meant Muslims, whom he perceived as a looming threat to the existence of Hindus.

I asked, in a country of 1.4 billion, where the majority was Hindu, Hinduism being the third largest religion in the world after Christianity and Islam, how were Muslims in India a threat to Hindus? Who lived in the constant fear of having their houses demolished, or being lynched by a mob driving home from work? In Ireland, a homicide makes it to the front page of every major publication in the country. In India, crimes against Muslim Indians and Dalits are hardly ever reported. With first-hand experience, we both laughed at the irony of this reality. In Ireland people were valued as human beings.

Most of all, I wanted to tell my friend that as a Christian I no longer felt safe in India, neither did I feel I belonged. That I was tired of being called a rice bag, a cultural traitor, with an insane desire to go around evangelizing and converting people. That it had become difficult seeing churches attacked and burnt, and parishioners beat up during our festivals. That I had grown up with Muslims, and watching their mere existence demonised with repeated calls for their slaughter was painful. That if it was Muslims bearing the maximum brunt of hatred now, it would be the Christians next. That his reasons for leaving the country and mine were very different. That I worried about my family and felt guilty I had left them behind. Did he know that feeling?

He seemed to agree with everything I was saying, yet there was something immutable in his stance. Who was I anyway, to come one day and challenge his views? Like he said, all opinions were personal and had no bearing on the other. But his opinion did matter. We were sitting in a foreign country where I considered myself safe. Because I didn’t feel safe in India, and that was directly because of his opinion and a good number of Indians who shared it.

To diffuse the tension, he laughed and said that he personally did not believe in religious discrimination, and had close Muslim and Christian friends. He apologetically repeated his first point, ‘people do anything for power. At the end the day, the powerful man rules. It’s sad, but it is the way it is.’

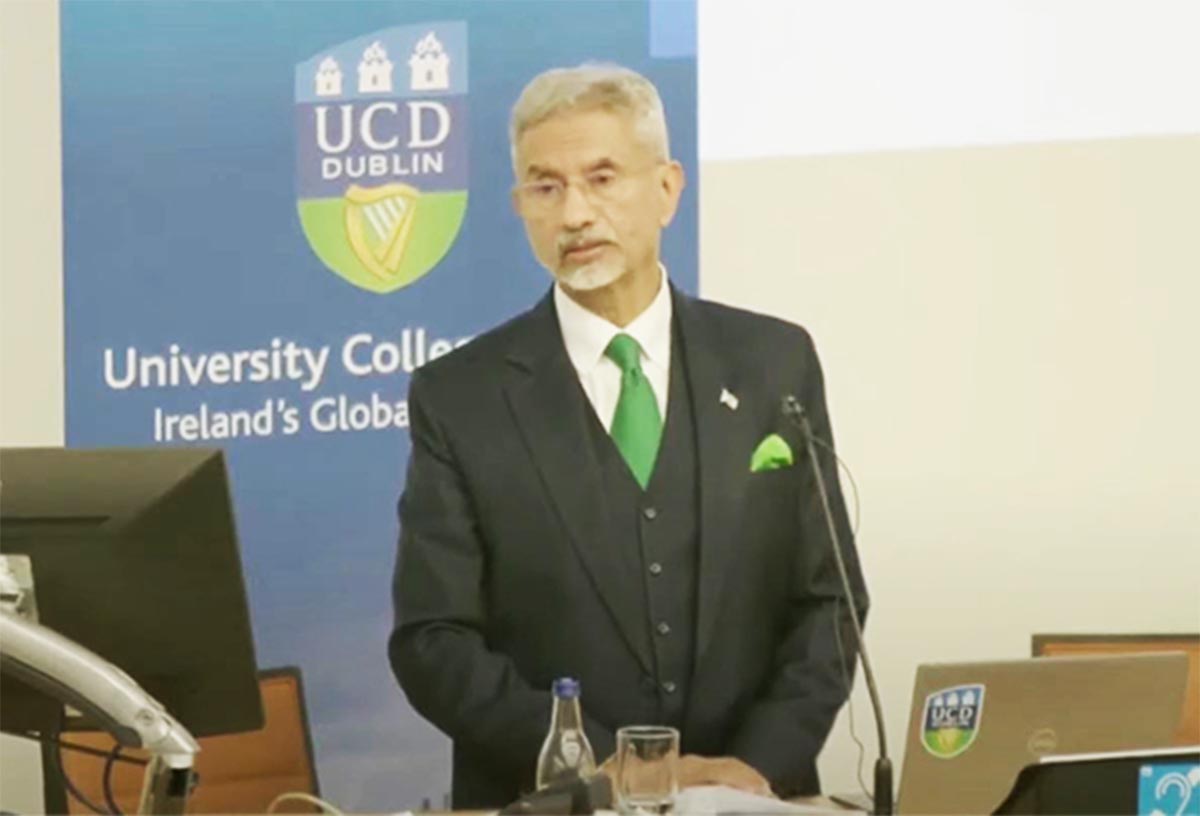

Forty-five minutes late, Dr. Jaishankar arrived dressed in a grey suit and tie, green for the occasion. Walking down the aisle, he was received with thumping applause. The meeting was attended by Irish and Indian ambassadors Kevin Kelly and Akhilesh Mishra as well as higher-ups and academics from UCD. The title of his lecture was ‘India’s View of the World’; an interesting topic in a time afflicted with polarisation, several major conflicts, and rising inequality. Yet apart from mentioning the developed world’s failure to meet SDGs (sustainable developmental goals), and vaguely reaffirming India’s neutrality on the Russia-Ukraine war, Dr. Jaishankar said little about what India thought of the world.

The talk seemed more about presenting India as a global superpower — robust growth, soon to be third largest economy, increasing number of airports, digitalised economy, and technological adeptness, were points he stressed on. Similarly, talk of global workplaces and collaboration in highly niche sectors like AI, drone manufacture, datacentres, and space exploration delivered in a ‘you need us more than we need you’ tone, took up most of the lecture.

Even the Q&A seemed curated with pre-selected questions to bolster this progressive and dominating image of the country.

The students were not disappointed. Every attempt at humour in the minister’s measured manner was met with laughter and delight. Every word clung to with rapt attention. My new friend laughed especially hard and clapped the loudest at the end of the talk. Looking around the audience, projecting my nausea for Dr. Jaishankar’s undeserved adulation, I realised a lot of the students were just happy to see someone in their corner. An hour before, while I waited in the queue outside the auditorium, I remembered being struck by the attire of the students around me. Most Indian students wear very basic winter jackets here. They come in dull colours, are of flimsy material, rarely fit, and are worn for the sake of warmth rather than style.

It’s not easy for Indian students studying abroad. Unlike the diversity focused college brochures, the study abroad experience for Indians is usually a lonely one, where students find themselves struggling to integrate into a new culture. They pay extraordinarily high fees (on loan) in a highly disparate currency, work stressful part-time jobs, and are for the most part broke the entire time. Their courses are chosen not out of passion, but to match the country’s Critical Skills List for the prospect of securing relevant jobs and permanent residence. They endure years of hardship to achieve one objective — making it, in a developed nation. In such conditions, symbolic gestures such as Dr. Jaishankar’s visit don’t go unappreciated.

Students cheered when Dr. Jaishankar called for a friendly visa-policy in the EU, and considered increasing shorter flights from Delhi to Dublin. These things matter to students. Hate politics, massive inequality, and upheaval of constitutional institutions back home aren’t relevant to their aspirations. If they manage to secure high-paying jobs and pay off their loans, then for all purposes, real or inflated, the government has done its work. Effectively, the government’s politics are benign and can be overlooked as long as growth, or at least the illusion of it, continued. It is selfish, wilfully ignorant, and prejudiced, but it works.

For the Indian diaspora there is another level of complexity, which is an internal feeling of cultural and racial insecurity. Indians want to be seen at par with everyone else. They wish to shed the timid, shy, thickly accented, English fumbling, and impoverished image the world has of them. Hence, the obsession with representation.

It was enough that Dr. Jaishankar was a high ranking minister, a charming man in a suite who spoke with erudition and was highly educated (He is an author of several books and has a Ph.D in International Relations). He deserved adulation not because of what he said or did, but because of what he represented to us on that stage. Speaking in front of Irish officials and university authorities, he represented what Indians could be — powerful and respected.

The BJP’s idea of development and progress is the same — symbolic gestures that indulge the aspirations and deep insecurities of the Indian psyche. The Vande Bharat train, grand airports, the perfunctory language of globalism, high growth, data, drones, and AI, are developmentally symbolic efforts to make India worthy of itself in the Western gaze. India’s view of the world is really India’s view of itself. To the Indian student subsisting on supermarket bought sandwiches and renting a dingy room in the suburbs, the narrative of the unstoppable Indian is something to draw hope and inspiration from. It validates their struggle.

The humiliating spectacle of Indian citizens handcuffed, shackled at their feet and dragged through a runway, and the governments’ failure to address it, is a case for cosmic irony. What can India say against ill-treatment of Indians overseas when it has itself become a model for far-right nationalism under the Hindutva project? Disdain for DEI policies in American Companies (which affect Ireland as well), curtailing H1Bs, and the ‘Normalise Indian hate’ climate currently unfolding in the Trumpian dystopia hurts Indians abroad. India has lost its moral ground in voicing out against racism because of what it does to its own, because nationalism is based on the consolidation of identities and suppression of all others. As countries progress toward the right and ire against immigrants rises, India shouldn’t be surprised when it points the finger and finds three pointing back — Muslim, Dalit, and Christian.

I don’t think my friend hated minorities. But the privilege of not being at the receiving end, occupied in his own aspirational struggle led him to have a certain blindness. In this case, we’ll call it prejudice. It doesn’t occur to him that Indians do well regardless of the hype of supremacy, because we are a brilliant people, and succeed wherever we go.

(The author is a student at the University College Dublin-UCD)

Related:

Why is the Govt of India silent on the spurt of attacks on Muslims, Adivasis?