At the heart of the Indian republic lies the principle that governments derive their legitimacy from the consent of the governed, expressed through free and fair elections. This promise, enshrined in the Constitution and reinforced through decades of jurisprudence, is not a procedural formality but the very foundation of democratic self-rule. Without it, the constitutional edifice that sustains the republic begins to hollow out.

In recent months, however, this foundational promise has come under unprecedented strain. Allegations of systematic irregularities in the electoral process have shaken public confidence in the Election Commission of India (ECI)—the very institution entrusted under Article 324 of the Constitution with the “superintendence, direction and control” of elections. What is at stake is not only the outcome of specific contests but the credibility of the electoral machinery itself.

The controversy was ignited most forcefully by leader of the opposition (loP) in the Lok Sabha and Congress member of parliament (MP) from Rae Bareily in Uttar Pradesh, Rahul Gandhi’s recent presentation on “vote chori” (vote theft), where he alleged that constituencies such as Bengaluru Central were decisively tilted through fraudulent voter roll practices (August 7). He was joined soon after by member of parliament (MP) from Kannauj in Uttar Pradesh, Akhilesh Yadav of the Samajwadi Party, who revealed that as far back as 2022 they had submitted 18,000 notarised affidavits documenting voter list discrepancies in Uttar Pradesh—only to have them ignored. Adding weight to these charges, the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) announced in August 2025 that it would move the Orissa High Court over what it described as large-scale irregularities in the 2024 elections in Odisha. Together, these accusations signal not a partisan grievance but a cross-party consensus that the electoral referee has failed in its duty. Before the August 7 press conference that continues to create serious ripples, Rahul Gandhi had on June 8, penned a multi-edition piece on “Match-fixing in Maharashtra” where, he had, once before, flagged the issue of voters tolls, writing, “Voter rolls and CCTV footage are tools to be used to strengthen democracy, not ornaments to be locked up. The people of India have a right to be assured that no records have been or will be trashed.”

The allegations are serious and specific. They include claims of duplicate voters registered in multiple constituencies, entries with fake or non-existent addresses, dozens of individuals shown as living in single residences or even commercial establishments, blurred or invalid photographs, and misuse of Form 6 intended for first-time voters. Equally troubling are charges of large-scale deletion of legitimate voters—particularly Muslims, Dalits and Yadavs in Uttar Pradesh—amounting to targeted disenfranchisement. When placed against narrow margins in key constituencies, these irregularities take on profound significance: as Rahul Gandhi put it, “the theft of just 25 seats” could be enough to alter the national balance of power.

Compounding these charges are allegations of deliberate opacity and suppression of evidence by the ECI itself. Political parties have for years demanded access to machine-readable electoral rolls; instead, the Commission has restricted itself to scanned, image-based PDFs that prevent meaningful digital scrutiny, especially recently. Requests for CCTV footage from polling stations have been rebuffed, and in December 2024, rules governing access to such records were amended with unusual haste to narrow transparency. The destruction of critical CCTV evidence, last-minute amendments to electoral regulations, and the Commission’s refusal even to meet parliamentary delegations of opposition MPs—all have deepened suspicions that lapses are not accidental but systemic. Further raising concerns, the ECI, on May 30, 2025, drastically cut the retention period for election video and photographic records to a mere 45 days after the announcement of results. This is a stark departure from previous norms that mandated preservation for durations ranging from 3 months to a full year. The ECI cited “recent misuse” of recorded material as justification, framing videography as an “internal management tool.”

The Commission, for its part, has denied all allegations, asserting that it operates with complete neutrality. In an August 17, 2025 press conference, Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) Gyanesh Kumar declared that “for the Election Commission, there is neither an opposition nor a ruling party. All are equal.” Yet, the Commission’s repeated insistence that selected complainants (elected officials of the ruling Bharatiya Janata party have not been served such an ECI ‘ultimatum’) file sworn affidavits before any inquiry will be undertaken stands in uneasy contrast with the law. Section 22 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950, explicitly empowers electoral officers to act suo moto to correct discrepancies—a power that cannot be abdicated. By shifting the burden onto citizens and parties, critics argue, the Commission has inverted its constitutional role.

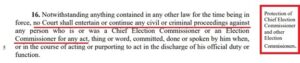

The controversy is further sharpened by the passage of the Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023, which extends sweeping immunity to Commissioners from civil or criminal proceedings for acts done “in the course of acting or purporting to act” in their official capacity. Coming just ahead of the 2024 general elections, this provision has raised fears that the institution most responsible for guaranteeing electoral fairness now stands shielded from accountability.

This article examines the crisis in its full dimensions. It sets out the allegations advanced by multiple political parties, most specifically those from the opposition, the Election Commission’s denials, the legal and constitutional framework that governs elections, and the mechanisms—statutory, judicial, and disciplinary—through which accountability may be enforced. Above all, it argues that the question today is not whether irregularities occurred in this or that constituency, but whether the constitutional machinery entrusted with safeguarding the franchise of nearly a billion Indians can still command the trust of the people.

Civil Society leads the charge

Even before the political opposition got into the act, citizens groups and former bureaucrats and judges had flagged the flailing unaccountability in the ECI, especially since 2017. The Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) and the Constitutional Conduct Group (CCG) –that set up the Citizens Commission on Elections (CCE) –are prominent among these. Of late, Vote for Democracy (VFD) has emerged as a platform that has, through data analyses, exposed the substantial discrepancies in the India’s electoral system.

Section I- Allegations against the Election Commission of India

The most direct challenge to the Election Commission’s credibility came from Rahul Gandhi’s presentation on “vote chori” (vote theft) in August 2025, where he laid out in detail what he described as “five mechanisms of electoral theft” from one assembly constituency in Bengaluru (Mahadevpura) of others in the Bengaluru Central parliamentary constituency. His claims were grounded in specific documentary evidence drawn from electoral rolls and booth-level data and took six months of manual work to unravel given the ECI’s refusal to supply easily accessible voter lists. The allegations extended beyond general suspicions to verifiable instances where the rolls reflected duplications, fictitious addresses, and suspiciously bulked entries.

Allegations by the Indian National Congress (Mahadevpura AC, Bengaluru Central)

- Duplicate voters

The first category of irregularities highlighted was the presence of duplicate entries. Rahul Gandhi’s team documented 11,965 cases where the same individual appeared multiple times within a constituency or even across different states. In some instances, the duplication went as far as the same EPIC (Electors Photo Identity Card) number being valid in multiple constituencies.

- Example: Gurkirat Singh Dang was found to appear more than once in the Mahadevapura rolls of Bengaluru.

- Other cases revealed names repeated across cities like Mumbai, Lucknow, and Varanasi, raising the prospect of the same individual voting in more than one location.

- Fake and invalid addresses

The second irregularity involved 40,009 cases of voters listed at non-existent or invalid addresses. Entries included house numbers listed simply as “0,” “–,” or “#,” with no corresponding physical address.

- Example: Booth No. 432 in Bengaluru reportedly carried multiple entries of voters residing at address “0.”

- Bulk voters at a single address

In another startling discovery, 10,452 cases showed dozens of voters being registered at tiny homes or even commercial premises.

- Example: House No. 35 listed 80 voters; House No. 791 had 46 voters.

- Perhaps most striking, the “153 Biere Club,” a brewery, was shown as the residence for 68 voters.

- Invalid photographs

A fourth category of manipulation involved 4,132 entries with micro-sized or blurred photographs, making it impossible for polling agents to identify voters accurately.

- Example: Booth Nos. 5 and 274 in Bengaluru contained such invalid photo entries.

- Misuse of Form 6

Finally, Rahul Gandhi alleged widespread misuse of Form 6, which is intended strictly for first-time voters. Instead, the form was used to create duplicate entries or multiple registrations.

- Example: Shakun Rani, a 70-year-old woman, was enrolled twice within two months under slightly different spellings and photographs, and both entries were recorded as having cast votes.

Together, these five methods painted what Rahul Gandhi described as a systematic architecture of electoral theft, not isolated errors. He alleged that in constituencies such as Bangalore Central (Mahadevapura segment), more than 1,00,250 fraudulent entries were found. The Congress candidate Mansoor Ali Khan lost this constituency by 32,707 votes. However, excluding the Mahadevapura segment—where the irregularities were most pronounced—Congress would have led by over 80,000 votes. “This is how the Bangalore Central seat was stolen,” Rahul Gandhi claimed.

At a broader level, he argued that this pattern extended across states: in Haryana, the Congress lost eight seats by a combined margin of only 22,779 votes out of over two crore cast. Nationally, he asserted, the BJP won 25 seats with margins under 33,000 votes. His conclusion was stark: Prime Minister Modi “only needed to steal 25 seats to stay in power in 2024.” Gandhi had also made strong claims on Maharashtra in June 2025.

Gandhi expanded these charges in his Indian Express article (“Match-fixing Maharashtra”, June 7, 2025), where he called the November 2024 Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha elections a textbook case of “industrial-scale rigging.” Citing Election Commission’s own statistics, he highlighted:

- An abrupt 41 lakh surge in registered voters between the May 2024 Lok Sabha elections and the November 2024 Assembly elections — exceeding even the state’s projected adult population.

- An unprecedented jump of 7.83 percentage points in turnout after 5 pm, equivalent to an extra 76 lakh votes appearing overnight without visible queues or extended polling hours.

- A disproportionate spike concentrated in about 12,000 booths across 85 constituencies where the BJP had underperformed earlier, with “miraculous” late additions averaging 600 votes per booth.

As a case study, Gandhi pointed to Kamthi, where the Congress’s vote tally remained stable between the two elections, while the BJP’s votes leapt by 56,000 — almost entirely explained by the sudden new additions. In his words, “It is not hard to discern the lotus shape of the magnet.”

He concluded that this “match-fixing” was made possible by a pliant Election Commission, opaque voter roll management, and post-poll amendments to restrict access to CCTV and electronic records. “Match-fixed elections are a poison for any democracy,” Gandhi warned.

Supporting him, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra warned that the BJP, having “stolen employment and public sector assets,” was now attempting to steal citizens’ votes. At rallies in Supaul and Darbhanga, she called the vote the “identity and foundation of citizenship,” cautioning that “if you allow your vote to be stolen, you will have no identity left, and your rights will be taken away.” She urged people to resist disenfranchisement, insisting that “we will not allow even a single vote of the poor to be stolen.”

The Congress and INDIA bloc thus framed the misuse of voter rolls, duplicate registrations, targeted late surges, and opaque revisions not as isolated lapses but as the deliberate subversion of universal adult franchise — the constitutional core of Indian democracy.

Allegations from the Samajwadi Party

If Rahul Gandhi’s allegations focused on manipulation through fraudulent inclusions, the Samajwadi Party (SP) brought forward evidence of large-scale, targeted deletions. On August 18, 2025, SP President Akhilesh Yadav revealed that the party had submitted 18,000 notarised affidavits to the ECI after the 2022 Uttar Pradesh Assembly elections, documenting widespread discrepancies in the rolls. These complaints go back to the 2022 assembly polls in the state and are also indicators that opposition parties have and had been complaining of malpractices for some years now though the Mahadevpura analysis by the Congress gave these allegations heft. Each affidavit had –following the ‘demand’ by the Commission–been signed, notarised, and formally acknowledged with receipts by the Commission. Yet, according to SP, not a single case was acted upon.

The SP alleged that the deletions were discriminatory, targeting Muslim, Dalit and Yadav voters ahead of the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, amounting to a breach of Article 326 of the Constitution, which guarantees universal adult franchise. In constituencies such as Mainpuri, the SP alleged that local officials from the Thakur community—the same caste as the state’s Chief Minister—used their authority and police resources to intimidate Opposition voters and prevent them from voting. These actions, the party argued, exceeded the legal powers of such officials and amounted to a misuse of state machinery.

Adding to this grievance, SP noted the Commission’s double standards. While the ECI demanded a sworn affidavit from Rahul Gandhi for his “vote chori” charges, it ignored the 18,000 affidavits already submitted by SP years earlier. For SP, this was proof of bias and dereliction, evidence that the Commission had chosen to shield the ruling party while denying legitimate complaints from the Opposition. Ram Gopal Yadav likened these deletions to a “backdoor NRC,” implying that disenfranchisement of voters was being used as a covert means of declaring citizens non-citizens.

Additional documented irregularities

Beyond Rahul Gandhi and SP, several other instances have surfaced that suggest deeper systemic flaws (many of these arose after citizens began their own independent investigations following Gandhi’s explosive analysis):

- Maharashtra (Palghar District): The case of Ms. Sushama Gupta, (in the 2024 Maharashtra Lok Sabha and assembly 2024 voters lists) whose name appeared six times across different localities in the electoral rolls, each with a distinct EPIC number. Astonishingly, five of these entries remained active, with one entry even bizarrely listing her as “gupta Gupta.” Despite multiple elections in 2024, local officials failed to rectify the duplicates, raising serious accountability concerns. Worse, these citizens’ investigations flagged the multiple presence of Sushama Gupta in Palghar, shockingly revealed that the District Election Officer(DEO), Govind Bobde, the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO), Shekhar Ghadge and the Booth Level Officer(BLO),Ms. Pallavi Sawant are common to and named against all these entries in all the six locations!!!

- Discrepancy between Roll Versions: In Maharashtra, two versions of the electoral roll were in circulation—one with photographs (seen on polling day) and one without (on the ECI portal). Serial numbers between the two did not match, suggesting that different lists were being used for Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha elections.

- Odisha (BJD Allegations): The Biju Janata Dal accused the Commission of large-scale discrepancies in the 2024 elections, including instances where the number of votes counted exceeded those recorded in EVMs, mismatches between Lok Sabha and Assembly segment tallies, and reports of 15–30% of polling occurring after scheduled hours. Despite submitting a detailed memorandum on December 19, 2024, the party received no response from the ECI. Frustrated, in August 2025, it announced its decision to move the Orissa High Court seeking judicial oversight and an independent audit.

Findings of the Vote for Democracy (VFD) report

Beyond political parties, civil society experts and former officials have also produced evidence of systemic irregularities. Last year, in July 2024, a citizen’s platform, Vote for Democracy (VFD) released, first an investigation into the sharp vote increase in the 2024 parliamentary elections (Report: Conduct of Lok Sabha Elections 2024-Analysis of ‘Vote Manipulation’ and ‘Misconduct during Voting and Counting’-Has the 2024 Mandate been stolen from the people of India) and followed up by another Report on the Haryana and Jammu and Kashmir state elections.

Continuing this work, on August 13, 2025, the citizen’s group Vote for Democracy (VFD), led by experts including M.G. Devasahayam, Dr. Pyara Lal Garg, Madhav Deshpande, and Prof. Harish Karnick, released a report titled “Dysfunctional ECI and Weaponisation of India’s Election System.” This report, based on official data from the ECI and the CEO Maharashtra, along with ground testimonies, presented a devastating critique of the 2024 Maharashtra Assembly elections.

The VFD’s central argument was that India’s electronic voting system (EVS) had been “weaponised” through four interlinked components:

- EVM microchips,

- VVPATs (Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trails),

- Symbol Loading Units (SLUs) with labile memory, and

- Electoral Rolls, where disenfranchisement has been rampant.

Together, the VFD argued, these vulnerabilities—especially after the system ceased to be fully stand-alone post-2017—created avenues for manipulation. The report warned starkly: “If allowed to continue, it could sound the death-knell of electoral democracy.”

Key findings in the VFD Report of Assembly elections, Maharashtra (2024):

- Unexplained midnight turnout surge

- Between 5 PM and midnight, official turnout jumped by 7.83%, adding nearly 48 lakh extra votes statewide.

- Constituencies like Nanded (+13.57%), Jalgaon (+11.11%), and Solapur (+10.63%) saw unprecedented spikes. Historically, late surges are minimal.

- Close margins, high stakes

- 25 seats were won by less than 3,000 votes, 39 seats by less than 5,000, and 69 seats by less than 10,000. Even minor anomalies could have altered outcomes.

- Erratic and unverifiable voter roll changes

- Between the May 2024 Lok Sabha elections and November 2024 Assembly elections—barely six months—the rolls ballooned by over 46 lakh voters.

- The additions were concentrated in 12,000 booths across 85 constituencies, many where the BJP had underperformed in May.

- At some booths, 600+ new voters were added after 5 PM, implying impossible voting hours.

- Discrepancies between official data sources

- On August 30, 2024, the ECI reported 9.64 crore voters, while the CEO Maharashtra reported only 9.53 crore — a gap of over 11 lakh.

- By October 30, 2024, the CEO’s figure had surged to 9.70 crore, an increase of 16 lakh voters in just 15 days.

- Large-scale data mismatches (2019–2024)

- In 2019, rolls grew by 11.6 lakh between LS and Assembly polls; in 2024, they grew by an astonishing 39.5 lakh in six months.

- Votes polled in the 2024 Assembly were 71 lakh more than in the Lok Sabha election earlier that year, a gap the ECI has not explained.

- Partisan vote surges

- BJP votes rose sharply between May and November 2024, averaging +28,000 votes per Assembly seat, without corresponding demographic change.

- In Kamthi, BJP gained 56,000 votes while Congress remained static. In Karad (South), 41,000 more votes were polled within six months.

- High-profile constituency anomalies

- In Nagpur South West (a seat associated with the Deputy CM), 29,219 voters were added in six months, beyond the permissible 4% verification limit.

- In Markadwadi village, Solapur, allegations surfaced that EVM results did not match actual votes, and police blocked attempts at verification.

- Procedural and technical failures

- Reports of routers near polling stations, power cuts during counting, EVMs arriving late at strong rooms, CCTV failures, and even strong room breaches.

- Mismatches between Form 17C and Control Unit counts were reported.

- VVPAT concerns persisted, including potential internet connectivity and lack of independent audits.

- Curtailment of transparency

- In December 2024, the ECI amended Rule 93 of the Conduct of Election Rules to restrict access to CCTV footage and Form 17C, days after a High Court had ordered their release.

- In May 2025, the retention of election CCTV footage was reduced from one year to 45 days, enabling destruction of evidence before legal challenges.

- Failure on hate speech

- Despite more than 100 complaints of hate speech during the Maharashtra polls, no visible action was taken by the ECI.

Patterns of Malpractice

Taken together — Rahul Gandhi’s allegations of fraudulent inclusions, the SP’s claims of targeted deletions, the BJD’s account of counting mismatches in Odisha, and the VFD’s expert-backed findings in Maharashtra — a consistent pattern emerges.

The alleged irregularities are not isolated errors but systemic failures involving both inclusion of fictitious voters and deletion of legitimate ones, compounded by opaque procedures and legal amendments that obstruct scrutiny. When seen in constituencies with razor-thin margins, these anomalies raise the gravest possible question: whether electoral outcomes in 2024 reflected the will of the people, or the failure of the institution mandated to safeguard it.

Section II: The Election Commission’s response

In the face of mounting allegations from opposition parties and civil society, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has consistently maintained its neutrality, often framing the charges as politically motivated attempts to undermine the institution’s credibility. The clearest articulation of this defence came on August 17, 2025, when Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar addressed a press conference in New Delhi. His statement sought to reassure the public that the Commission “stood, stands, and will stand with all voters — the poor, the rich, the elderly, women, youth, and all classes and religions — without any discrimination.”

Neutrality and equal treatment

At the core of the Commission’s defence was the claim that it cannot and does not discriminate among political parties. As the CEC put it, “for the Election Commission, there is neither an opposition nor a ruling party. All are equal.” The Commission emphasised that every political party is registered under the same statutory framework, and therefore must be treated equally. On this basis, it rejected allegations that it had ignored complaints by the Congress, Samajwadi Party, or BJD while demanding affidavits from Rahul Gandhi.

The affidavit demand

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the Commission’s stance has been its insistence that Rahul Gandhi and other opposition leaders file sworn affidavits to substantiate their claims of “vote chori.” The ECI cited Rule 20(3)(b) of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960, arguing that it required complainants who were not voters in the concerned constituency to submit their claims on oath.

The Commission framed this requirement as a matter of fairness to voters: “Should my voters be made criminals, and should the Election Commission remain silent? It’s not possible. An affidavit must be given, or an apology must be given to the country. There is no third option.” The CEC went further, warning that if an affidavit was not submitted within seven days, the Commission would treat all allegations as baseless.

Legal experts, however, have pointed out that Rule 20(3)(b) applies only during the claims and objections phase after publication of draft rolls, not after elections are concluded. Critics have argued that the Commission’s reliance on this provision is legally misplaced, especially when Section 22 of the Representation of the People Act, 1950 clearly empowers Electoral Registration Officers to act suo motu to correct rolls riddled with errors or duplications.

Defence on transparency

The Commission has also defended its controversial decisions to limit access to electoral data and CCTV footage. Responding to demands for machine-readable electoral rolls, the ECI invoked the Supreme Court’s 2019 decision in Kamal Nath v. ECI, where the Court upheld the Commission’s instructions to publish only image-based PDFs to protect voter privacy. According to the CEC, searchable digital rolls could enable misuse through profiling or data mining.

Similarly, when asked why CCTV footage from polling stations could not be shared, the Commission raised the spectre of privacy violations: “Should the Election Commission share CCTV videos of any voter, including our mothers, daughters-in-law, and daughters?” This line of argument was criticised by observers as a deflection, since demands for footage were aimed at verifying counting and procedural integrity, not at profiling individual voters.

Notably, the Commission had amended Rule 93 of the Conduct of Elections Rules in December 2024—barely 48 hours after the Punjab and Haryana High Court directed it to release Form 17C records and CCTV footage from the Haryana elections. The speed and opacity of this amendment, finalised and notified in under two days, raised concerns that transparency safeguards were being deliberately rolled back. In May 2025, further changes reduced the retention period of CCTV footage from one year to just 45 days, effectively ensuring destruction of evidence before legal challenges could progress.

The duplicate voter question

On the issue of duplicate voters, the Commission argued that even if a name appeared in two places, no voter could cast more than one vote, since EVMs record only a single input per person. “If a name is in two places in the voter list, how can a vote be stolen? It can’t. A voter can only cast one vote,” the CEC declared. The Commission also pointed out that the Representation of the People Act, 1950, under Sections 17 and 18, already prohibits multiple registrations and empowers officials to remove duplicates. The implication was that any failure to act was the responsibility of field officers, not of the Commission itself.

Response to timeliness and election petitions

Another theme of the Commission’s defence has been the timeliness of complaints. The CEC repeatedly noted that political parties had opportunities during the draft roll phase to raise objections, and that once elections were concluded, disputes should be pursued only through election petitions in High Courts within 45 days, as provided under the RPA 1951. In the Commission’s view, allegations raised months after results were declared—whether in Karnataka, Maharashtra, or Odisha—were politically motivated attempts to discredit a process that had already run its legal course.

Dismissal of systemic criticism

Beyond procedural defences, the Commission has also taken a combative tone against its critics. It accused political leaders of “aiming at the voters of India with a gun on the shoulder of the Election Commission” and warned that spreading “misinformation” about the rolls amounted to an insult to the Constitution. It argued that preparing and revising electoral rolls is a “shared responsibility” between Booth Level Officers, political parties’ Booth Level Agents, and voters themselves. In this framing, the Commission positioned itself less as an all-powerful guarantor of electoral integrity and more as a coordinator dependent on others’ diligence.

A defence that raises more questions

While the Election Commission’s August 17 press conference and subsequent clarifications sought to reassure the public, they have instead deepened the crisis of credibility. The affidavit demand appears legally unsustainable; the privacy justification for withholding data is widely seen as a cover for opacity; and the rapid amendments to rules governing transparency suggest defensiveness rather than neutrality.

Moreover, by shifting responsibility onto Booth Level Officers, Electoral Registration Officers, and even political parties themselves, the Commission risks appearing to deny the very plenary duty vested in it under Article 324 of the Constitution. Far from closing the controversy, the ECI’s responses have opened up new lines of critique—particularly whether a constitutional body can so openly disclaim accountability for the fairness of the electoral process it is mandated to uphold.

Section III- Political parties and the Court

On August 22, the Supreme Court issued significant directions in the Bihar Special Revision of Electoral Rolls (SIR) matter, easing the process for citizens excluded from the draft rolls. The Court ruled that such individuals may now file applications for inclusion through online mode, with no requirement for physical submission of forms.

A Bench comprising Justices Surya Kant and Joymalya Bagchi further clarified that applicants may attach any of the eleven documents prescribed by the Election Commission of India or their Aadhaar card to support their claims for inclusion. This is an ongoing matter with several petitions filed challenging the controversial Bihar SIR, the lead petitioners being the Association of Democratic Reforms. The next hearing is scheduled for September 8.

To ensure effective facilitation, the Court directed that all 12 recognised political parties in Bihar instruct their Booth Level Agents to assist voters in their respective constituencies in completing and submitting the forms. It also impleaded these parties as respondents in the proceedings, where they were not already petitioners.

In terms of public transparency, the Court mandated that the Chief Electoral Officer (CEO) of Bihar publish the relevant information on the official website, with documents searchable using EPIC numbers. The Election Commission was also asked to issue public notices making clear that Aadhaar can be furnished at the time of filing claims for inclusion. Additionally, the Commission must ensure wide publicity of the process through newspapers, television, and social media, and guarantee that the final electoral list is available online.

Significantly, in requiring searchable publication of the electoral rolls, the Court departed from its earlier 2018 ruling in Kamal Nath v. Election Commission, which had held that voter lists need not be made available in such a format.

1. BJD to move Orissa HC over irregularities in 2024 Lok Sabha

Eight months after alleging large-scale irregularities in the 2024 Assembly and Lok Sabha elections in Odisha, the Biju Janata Dal (BJD) has decided to move the Orissa High Court, citing inaction by the Election Commission of India (ECI). Former MPs Amar Patnaik, Sarmistha Sethi, and MLA Dhruba Charan Sahu stated that BJD had earlier flagged three major discrepancies. First, the number of votes counted exceeded those in EVMs across all 21 Lok Sabha constituencies—booth-level differences ranged from 660 to 784 votes. Second, there were mismatches between votes polled in Lok Sabha constituencies and their seven corresponding Assembly segments, with discrepancies up to 4,056 votes. Third, 15–30% of polling reportedly occurred after scheduled hours.

Despite submitting a memorandum on December 19, 2024, the ECI has not responded or shared Form 17C with candidates. The BJD, supported by Congress concerns, now seeks judicial intervention and an independent audit of the election process.

Fact Check – Samajwadi Party Chief and MP, Akhilesh Yadav on August 17 (same day of ECI PC) wrote on his X handle that the Election Commission is claiming that they have not received the affidavits provided by the Samajwadi Party in UP; they should check the acknowledgment receipt issued by their own office as proof of receipt of our affidavits. This time, we demand that the Election Commission provide an affidavit stating that the digital receipt sent to us is authentic, otherwise, not only the ‘Election Commission’ but also ‘Digital India’ will come under suspicion.

जो चुनाव आयोग ये कह रहा है कि हमें यूपी में समाजवादी पार्टी द्वारा दिये गये ऐफ़िडेविट नहीं मिले हैं, वो हमारे शपथपत्रों की प्राप्ति के प्रमाण स्वरूप दी गयी अपने कार्यालय की पावती को देख ले। इस बार हम मांग करते हैं कि चुनाव आयोग शपथपत्र दे कि ये जो डिजिटल रसीद हमको भेजी गयी है वो… pic.twitter.com/9A4njvF9Tw

— Akhilesh Yadav (@yadavakhilesh) August 17, 2025

- Protection granted to the Chief and Other Election Commissioners

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Bill, 2023—passed during the Winter Session of Parliament and notified with unusual urgency on January 2, 2025—includes a significant provision under Section 16. This clause explicitly prohibits any civil or criminal proceedings against the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC) or other Election Commissioners (ECs) for any act undertaken “in the course of acting or purporting to act” in their official capacity.

Following the enactment of the law, opposition parties raised specific and serious allegations of electoral bias and manipulation involving the Election Commission. Instead of addressing these concerns or engaging in public clarification, the Commission has remained silent, further diminishing public confidence in the institution. The decision to extend such sweeping legal immunity just ahead of a national election cycle raises fundamental questions about motive and accountability.

Congress claimed that the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), in collusion with the Election Commission, engaged in manipulative practices, with CEC Rajiv Kumar allegedly benefiting from the legal protection provided under the new Act.

Section IV- Fact check and legal framework

The Election Commission’s August 17 defence rested on three pillars: that complaints must be filed through affidavits; that duplicate names do not, by themselves, enable electoral fraud; and that constraints on access to electoral data are necessary for privacy. A closer examination of the Constitution, the Representation of the People Acts, and judicial precedent shows that each of these claims is, at best, a partial truth — and at worst, a fundamental misreading of the law.

- Article 324: The plenary Constitutional mandate

Article 324 of the Constitution vests the ECI with the power of “superintendence, direction, and control” of elections to Parliament, State legislatures, and the offices of President and Vice-President.

- The Supreme Court, in Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner (1978), held that Article 324 is a plenary power that equips the Commission to act in situations unprovided for in law, to ensure free and fair elections.

- In Election Commission v. Ashok Kumar (2000), the Court reiterated that the Commission’s authority extends beyond statutory confines, because free and fair elections are part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

Thus, any claim that the Commission is a mere coordinator of Booth Level Officers or that responsibility lies with “field functionaries” contradicts constitutional text and judicial doctrine. The ECI cannot outsource accountability: it is the constitutional guarantor of the integrity of the franchise.

- Representation of the People Act, 1950: Electoral rolls

The RPA 1950 assigns exclusive responsibility for the preparation and maintenance of electoral rolls to the Commission and its officers. Several provisions are directly relevant:

- Section 15: Mandates preparation of electoral rolls under the “superintendence, direction, and control” of the Election Commission.

- Section 17: Prohibits a person from being registered in more than one constituency.

- Section 18: Prohibits multiple entries for the same person within a constituency.

- Section 22: Crucially, empowers the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO) to correct entries in the roll suo motu or on application, including deletion of duplicates and correction of errors.

The Commission’s claim that it cannot act without affidavits ignores this explicit suo motu power. Affidavits may be a procedural tool during the claims and objections stage, but the law imposes a proactive duty on officials to cleanse the rolls.

Most crucially, the onus is on the ECI and all its tiers of officials who are legally responsible for the state of electoral rolls.

This accountability is not only constitutional but also judicially forewarned. In A.C. Jose vs. Sivan Pillai and Ors. (1984), Justice S. Murtaza Fazal Ali observed:

“If the Commission is armed with such unlimited and arbitrary powers and if it ever happens that the persons manning the Commission shares or is wedded to a particular ideology, he could by giving odd directions cause a political havoc or bring about a constitutional crisis, setting at naught the integrity and independence of electoral process, so important and indispensable to the democratic system.”

These words, written four decades ago, now appear almost prophetic. They highlight that when the ECI disowns responsibility or aligns itself too closely with ruling interests, it risks not only immediate electoral malpractice but also a systemic constitutional breakdown.

- Representation of the People Act, 1951: Conduct of elections

The RPA 1951 governs the actual conduct of elections and remedies for irregularities:

- Section 100 provides that an election can be declared void if the result was “materially affected” by improper acceptance or rejection of votes, or by “non-compliance with the provisions of the Constitution or of this Act or of any rules or orders made under this Act.”

- Section 129 empowers the Commission to delegate functions, but ultimate responsibility remains with it.

Judicial precedent has consistently underscored that the RPA’s remedies are not substitutes for the Commission’s constitutional duty under Article 324. The Commission cannot shield itself by insisting that aggrieved parties should pursue election petitions alone.

- Case Law: Free and fair elections as the basic structure

- Indira Nehru Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975): The Supreme Court held that free and fair elections are part of the Constitution’s basic structure. Any state action undermining this principle is unconstitutional.

- PUCL v. Union of India (2003): Affirmed the right to know as part of the right to free expression under Article 19(1)(a), grounding voter access to candidate information in constitutional rights.

- Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) v. Union of India (2002): The Court insisted that transparency in electoral processes is essential to democracy.

- Mohit Kumar v. ECI (Allahabad High Court, 2014): The Court held that electoral rolls must be error-free, and lapses in inclusion or deletion are actionable failures of the Commission.

- G.S. Iqbal v. Union of India (Gauhati High Court, 2021): Confirmed that the Commission cannot rely solely on political parties or complainants; it must proactively ensure the rolls’ integrity.

Together, these precedents make clear that the ECI is not a passive referee but the active custodian of electoral fairness.

- The Affidavit Defence: A legal misstep

By invoking Rule 20(3)(b) of the Registration of Electors Rules, the Commission attempted to shift responsibility to complainants. But this provision is limited to the claims and objections process after the publication of draft rolls. Once elections are over, and irregularities are alleged in final rolls, the Commission cannot hide behind affidavit requirements. Section 22 of RPA 1950 empowers and mandates, suo motu correction at any time.

The affidavit demand, therefore, is not only legally weak but also undermines public confidence, since it suggests that without sworn testimony, irregularities do not exist — a stance directly at odds with the law.

- Transparency, privacy, and the Kamal Nath case

The Commission’s reliance on Kamal Nath v. ECI (2019) to justify denying machine-readable rolls also deserves scrutiny. In that case, the Court upheld restrictions on digitised rolls primarily to prevent bulk misuse of personal data. However, the ruling cannot be read to justify opacity in all contexts, especially when legitimate requests for machine-readable formats are aimed at detecting systemic fraud, not profiling voters.

Similarly, the Commission’s privacy-based defence for withholding CCTV footage is a red herring. Footage requests have been narrowly tailored to verify adherence to procedure (e.g., whether EVMs were properly sealed, whether strong rooms were breached). To frame these as intrusions into the “privacy of mothers and daughters” is a rhetorical deflection, not a legal argument.

- Shifting blame to field officers

The ECI has argued that failures in roll management are attributable to Booth Level Officers (BLOs), Electoral Registration Officers (EROs), and District Election Officers (DEOs). While these officials execute the process, they are legally deemed to be acting on behalf of the Commission.

The Supreme Court in Mohinder Singh Gill (1978) made clear that “the Commission is responsible for the conduct of elections in their entirety.” Delegation does not diminish accountability. By disclaiming responsibility for its own officers’ lapses, the ECI undermines the very logic of Article 324.

- Accountability beyond elections

The Commission’s insistence that remedies lie only through election petitions under the RPA 1951 overlooks a broader point. Free and fair elections are not only about post-facto adjudication of disputes but about ongoing institutional duty. As the Supreme Court observed in Ashok Kumar (2000), the Commission has a continuing obligation to intervene “at every stage” to preserve electoral fairness.

Conclusion of the legal fact check

In light of the constitutional text, statutory duties, and judicial precedent, the Commission’s defences appear unsustainable. Affidavits are not legally necessary; privacy cannot override transparency in matters of public verification; and responsibility cannot be offloaded onto subordinate officers. The law is clear: the Election Commission of India bears ultimate accountability for the preparation of clean rolls, the conduct of free and fair elections, and the preservation of public confidence in the democratic process.

Section V: Accountability and immunity

The question that inevitably follows from the factual and legal critique of the Election Commission’s role is: who bears responsibility, and how can accountability be enforced? The Constitution, statutes, and case law leave little doubt that the Commission is the ultimate guarantor of electoral integrity. Yet, in recent years, legal and institutional changes have erected barriers to holding it answerable — creating what critics describe as a “zone of impunity” around India’s electoral machinery.

- The chain of responsibility

The Election Commission has repeatedly argued that lapses in the preparation of electoral rolls or conduct of polling are attributable to Booth Level Officers (BLOs), Electoral Registration Officers (EROs), District Election Officers (DEOs), and Chief Electoral Officers (CEOs). This argument is legally flawed.

- Under the RPA 1950 and 1951, these officials are appointed or deemed to be officers of the Commission for the purposes of elections.

- Their acts and omissions are therefore acts of the Commission itself, not of independent authorities.

As the Supreme Court clarified in Mohinder Singh Gill (1978), the Commission “is responsible for the conduct of elections in their entirety.” Delegation does not erase accountability. When duplicate entries remain in rolls, when legitimate voters are deleted, or when CCTV footage is destroyed, it is not a failure of isolated officers but a direct dereliction of duty by the Commission.

- Constitutional duty cannot be waived

The Commission’s repeated claim that irregularities are external manipulations mischaracterises its mandate. Article 324 does not allow the Commission to disclaim responsibility for breaches in the system it supervises. As the Supreme Court observed in Ashok Kumar (2000), the Commission has a duty “at every stage” of the process to ensure fairness.

Thus, failures in preventing duplicate entries, fake addresses, misuse of Form 6, or suppression of transparency rules are not incidental lapses. They represent constitutional failures traceable directly to the Commission.

- The 2023 commissioners’ immunity law

The Chief Election Commissioner and Other Election Commissioners (Appointment, Conditions of Service and Term of Office) Act, 2023 introduced a sweeping immunity clause:

“No civil or criminal proceedings shall lie against the Chief Election Commissioner or other Election Commissioners in respect of any act done or purporting to be done in the course of acting or purporting to act in their official capacity.”

This clause insulates Commissioners personally from prosecution or liability, even if their actions — or inactions — facilitated systemic malpractice. The immunity is broader than that available to most constitutional authorities and, unlike parliamentary privileges, has no internal mechanism of accountability.

Critics argue that this provision undermines the very logic of constitutional governance. By shielding Commissioners from legal scrutiny, it creates a moral hazard: those entrusted with safeguarding elections are effectively placed above the law. In practice, this has emboldened the Commission to dismiss allegations and rebuff requests for transparency without fear of consequences.

- Judicial oversight and election petitions

The Commission frequently points to election petitions under the RPA 1951 as the sole route for redress. While judicial oversight remains an important check, it suffers from two structural limitations:

- Delay: Election petitions often take years to resolve, by which time the electoral cycle has moved on.

- Scope: Petitions address individual constituencies, not systemic failures across states or nationwide.

As a result, even when irregularities are documented, there is little immediate accountability for the Commission itself.

- Criminal and disciplinary liability

Beyond constitutional and statutory obligations, failures in electoral management may also entail criminal and disciplinary consequences:

- Section 32 of the RPA 1950: imposes penalties on officials who fail to perform their duty in relation to rolls.

- Section 134A of the RPA 1951: penalises any officer guilty of misconduct at elections.

- Indian Penal Code / Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS): provisions on forgery, fraud, and destruction of evidence may apply when officials knowingly permit duplicate entries, fake addresses, or deletion of legitimate voters.

Since these officials act as representatives of the Commission, ultimate accountability returns to the ECI itself. Immunity for Commissioners does not extend to field officers, but it raises an uncomfortable asymmetry: the lowest-level BLO may face penalties, while Commissioners who oversee systemic failures remain shielded.

- Institutional evasion of responsibility

The combined effect of these legal frameworks and recent amendments is a troubling paradox. On the one hand, the Commission asserts absolute neutrality and denies wrongdoing. On the other, it distances itself from accountability by invoking:

- the personal immunity granted to Commissioners in 2023,

- the supposed responsibility of subordinate officers, and

- the narrow remedy of election petitions.

This evasion of responsibility corrodes public confidence. As one critic noted, “the referee cannot declare itself above the rules of the game.”

- Restoring accountability

If electoral democracy is to retain legitimacy, accountability must be restored through:

- Judicial review of the 2023 immunity clause,

- Parliamentary oversight through Standing Committees,

- Statutory audits of rolls and EVMs by independent agencies, and

- Transparency measures, including mandatory publication of machine-readable rolls and retention of CCTV evidence for at least one year.

Without such checks, the Commission risks sliding into unassailable opacity, undermining the very legitimacy of the electoral system it exists to protect.

Section VI- Broader democratic implications

The controversy surrounding the Election Commission of India (ECI) is not a matter of mere administrative lapses. At stake is the credibility of India’s electoral democracy itself. Elections are not simply mechanisms for transferring power; they are rituals of legitimacy, binding citizens and the state through a collective act of trust. When that trust erodes, the democratic contract begins to fray.

- Erosion of public trust

At the heart of the current crisis lies a profound erosion of trust. Allegations of duplicate voters, targeted deletions, and unexplained surges in turnout are not easily dismissed as technical errors when they are corroborated across multiple states and by independent experts. The perception that elections are no longer fair is itself corrosive. As the Supreme Court has often recognised, democracy must not only be fair but must also appear to be fair.

For millions of voters — particularly those whose names disappeared from rolls in Uttar Pradesh or whose constituencies in Maharashtra saw implausible surges of late-night voters — the experience has been one of exclusion and disenfranchisement. This breeds alienation, particularly among minorities and marginalised groups, who come to view the electoral process as structurally biased against them.

- Disenfranchisement as a tool of control

The Samajwadi Party’s claim that 12 per cent of Muslim, Dalits and Yadav voters were systematically deleted from rolls in parts of Uttar Pradesh highlights the potential weaponisation of electoral administration. Disenfranchisement through bureaucratic deletion is a subtler but no less effective form of political exclusion than overt intimidation.

When voter rolls become instruments of selective exclusion, elections cease to be contests of ideas and instead become contests of manipulation. This undermines the principle of universal adult suffrage, the bedrock on which India’s democratic identity rests.

- Opacity as an institutional culture

The Commission’s handling of transparency requests points to a deeper institutional problem: a culture of opacity. Its insistence on image-based PDFs instead of machine-readable rolls, its refusal to release CCTV footage, and its hurried amendments to restrict access to election records all signal a posture of secrecy rather than accountability.

Opacity may serve the short-term interest of insulating the Commission from criticism, but it exacts a long-term cost. Without transparency, citizens cannot independently verify the fairness of elections. Trust becomes contingent on blind faith in the institution — a faith now visibly waning.

- Institutional drift and partisan perceptions

Once perceived as one of the most respected constitutional authorities in India, the ECI now faces accusations of institutional drift. The willingness to entertain ruling party complaints while dismissing opposition grievances has reinforced suspicions of partisan bias.

Even if the Commission is not actively partisan, the perception of partiality is itself damaging. As Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975) underscored, electoral legitimacy is inseparable from the appearance of fairness. When one side believes the umpire is tilted, the entire contest is delegitimised.

- Democratic legitimacy at risk

The broader implication of these failures is the risk of democratic illegitimacy. If citizens come to believe that outcomes are pre-determined by manipulation of rolls or machines, the incentive to participate diminishes. Low turnout, disaffection, and withdrawal from electoral politics follow — hollowing democracy from within.

This is not merely theoretical. Evidence from other democracies shows that once public confidence in electoral institutions collapses, restoring it is extraordinarily difficult. Trust, once lost, does not return quickly. India, with nearly a billion voters, cannot afford such a collapse.

- International and constitutional reputation

As the world’s largest democracy, India’s electoral integrity has long been a source of global legitimacy. International observers and comparative scholars have often cited the Election Commission as a model of independent electoral administration. That reputation is now under strain.

Domestically, the crisis tests the basic structure doctrine of the Constitution. Since free and fair elections are judicially recognised as part of the basic structure, any systemic failure in the electoral process is not simply a political problem but a constitutional breakdown.

- The risk of normalisation

Perhaps the gravest danger is the normalisation of irregularities. When allegations of “vote chori” are routinely dismissed, when CCTV footage is destroyed as a matter of course, and when voters quietly accept that their names may vanish from rolls, manipulation becomes the new normal. Democracy then continues in form but is emptied of substance.

- A moment of reckoning

The present moment, therefore, is a constitutional reckoning. India must decide whether its electoral democracy will remain a genuine mechanism of consent or devolve into a hollow ritual managed by an unaccountable bureaucracy. The outcome will not only determine the credibility of the 2024 elections but will shape the trajectory of Indian democracy for decades to come.

Section VII- Pathways to reform

The depth of the current crisis makes it clear that cosmetic adjustments will not suffice. If India’s electoral democracy is to retain legitimacy, structural reforms are essential — reforms that restore transparency, re-establish accountability, and rebuild public trust in the Election Commission of India (ECI).

- Restoring transparency

Transparency is the first casualty of the Commission’s current posture and must be the first area of reform. Steps include:

- Machine-readable electoral rolls: Rolls must be published in open, searchable formats (CSV/Excel) to allow independent verification by parties, civil society, and researchers. Privacy concerns can be addressed by masking sensitive details while retaining fields necessary for scrutiny.

- Public access to CCTV footage: Footage from polling stations and counting centres should be retained for at least one year and made available to parties and courts as a matter of right.

- Publication of Form 17C data: Polling station-wise turnout and vote tallies must be released promptly in standardised, verifiable formats.

- Rollback of restrictive amendments: The December 2024 changes to Rule 93 of the Conduct of Election Rules, which curtailed access to records, should be repealed.

- Independent forensic audits

Confidence in the electoral process requires independent verification of its technical infrastructure:

- EVMs and VVPATs should be subject to periodic, randomised forensic audits by independent technical experts, with reports placed in the public domain.

- Symbol Loading Units (SLUs), identified by the Vote for Democracy (VFD) report as particularly vulnerable, must be independently certified after every election.

- Random hand-counts of VVPAT slips across a significant sample (well beyond the current 5 per constituency) should be mandated by law.

- Judicial review of immunity

The sweeping immunity granted to Commissioners under the 2023 Act requires urgent reconsideration. The Supreme Court, either through a direct challenge or in the course of electoral litigation, must clarify whether such immunity is compatible with constitutional principles of accountability. A constitutional body entrusted with safeguarding democracy cannot be placed entirely beyond judicial scrutiny.

- Decentralisation of electoral management

The VFD report’s recommendation for decentralisation deserves serious attention. State Election Commissions, which already oversee local body elections, could be entrusted with conducting Assembly polls, leaving the central ECI to focus on Lok Sabha elections. This would diffuse concentration of power and reduce the perception of centralised bias.

- Parliamentary oversight

Parliament’s role in overseeing the ECI has been minimal. A Standing Committee on Electoral Integrity could be instituted, tasked with examining post-election reports, investigating irregularities, and summoning Commissioners for testimony. Such oversight would not compromise independence but would reinforce accountability.

- Strengthening legal remedies

- Time-bound adjudication: Election petitions must be disposed of within six months, failing which the winning candidate’s election could be provisionally suspended.

- Collective remedies: Mechanisms should exist for systemic irregularities — such as mass deletions or unexplained turnout surges — which go beyond the scope of individual constituency petitions.

- Criminal liability: Sections 32 (RPA 1950) and 134A (RPA 1951) must be enforced rigorously against officials guilty of misconduct, and liability must extend upward to supervisory officers.

- Protecting voter rights

At the centre of reforms must be the voter. Measures should include:

- Statutory guarantee against arbitrary deletions: Voter names should not be removed from rolls without written notice and opportunity for appeal.

- Grievance redressal mechanisms: Voters must have accessible, time-bound remedies (including digital portals and helplines) to address roll discrepancies.

- Independent observers: Appointment of citizen observers to monitor disenfranchisement and report directly to the judiciary, not only to the Commission.

- Rebuilding institutional credibility

Ultimately, no reform will succeed without cultural change within the Commission itself. The ECI must return to its original ethos: that of a fiercely independent, fearless institution guarding democracy. Commissioners must adopt a posture of humility and responsiveness, rather than defensiveness and denial.

The Commission’s prestige was built not on legal immunities but on moral authority — on the perception that it stood above politics. Restoring that authority requires openness, candour, and a willingness to confront failures.

- A reform agenda for the future

The path forward is clear:

- Transparency in data,

- independent audits of technology,

- judicially reviewable accountability,

- parliamentary oversight, and

- voter-centric protections.

Together, these reforms can re-anchor India’s electoral democracy in constitutional principle and public trust. Without them, the risk is not merely of flawed elections but of a gradual hollowing of the democratic state itself.

- Ensuring fair and transparent revision of electoral rolls

The ongoing controversy around Bihar’s Special Intensive Revision (SIR) highlights the dangers of abrupt, opaque, and overly aggressive roll-cleaning exercises. Structural reforms must therefore include safeguards to ensure that revisions are conducted in a fair, transparent, and citizen-friendly manner:

- Predictable timing and notice: Large-scale revisions must not be sprung on voters without adequate preparation or awareness. Sufficient notice and staggered timelines must be given to avoid mass confusion.

- Clarity of procedure: Instructions to Booth Level Officers (BLOs) and supervisory officers must be detailed, explicit, and made public — including criteria for acceptance, rejection, and scrutiny of enumeration forms.

- Correction opportunities: Prefilled forms based on existing data should allow voters to correct errors, rather than replicating inaccuracies and carrying them forward.

- Transparency in disclosures: The ECI must publish real-time data on forms submitted, documents attached, and grounds for rejection. Abruptly stopping disclosure, as in Bihar’s SIR, fuels suspicion and undermines trust.

- Respecting voter choice: Voters who migrate temporarily must not be disenfranchised at their place of origin without due choice, just as NRIs, defence personnel, and parliamentarians are allowed to exercise preference.

- Avoiding overreach on citizenship questions

Article 326 of the Constitution makes clear that citizenship is a condition of eligibility to vote, but it is not for the Election Commission to embark on a parallel determination of citizenship. Former Election Commissioner, Ashok Lavasa, rightly noted in his piece with The Tribune that separating pre-2003 and post-2003 electors on “presumed citizenship” grounds was fallacious and unnecessarily inflammatory. Future reforms must ensure that:

- The ECI focuses strictly on eligibility and residence, leaving citizenship determinations to the legal and administrative processes already in place.

- No elector is treated as “ineligible” merely because of “permanent migration” — at most, such a voter should be shifted across rolls, not erased.

- Embedding proportionality in electoral roll management

A comprehensive exercise such as SIR should not resemble a punitive raid or enforcement sweep. Instead, it must be designed as a civil, rule-based, participatory process aimed at correcting errors without alienating voters. Key principles include:

- Compassionate administration: As Lavasa observes, the Commission must adopt the same empathetic approach that it has historically followed in balancing accuracy with inclusion.

- Weeding without harming the crop: In Lavasa’s metaphor, voter roll cleansing should emulate a farmer removing weeds without damaging the standing crop. The integrity of the roll must be secured without undermining citizens’ confidence in their right to vote.

- Public cooperation: The ECI must actively enlist citizen cooperation, rather than impose a top-down compliance burden that leaves voters scrambling to “save” their franchise.

Conclusion: Reclaiming the Republic’s democratic soul

The present crisis surrounding the Election Commission of India is not a passing controversy, nor a partisan quarrel. It strikes at the heart of the constitutional promise that the people of India are governed by their freely expressed will. The allegations of manipulated voter rolls, opaque procedures, and selective disenfranchisement are not just administrative failures — they are existential threats to democracy itself.

At the core lies a constitutional paradox. The Commission is vested under Article 324 with the most sweeping mandate in Indian public law: the “superintendence, direction and control” of elections. It is the sole institution charged with guaranteeing the sanctity of the franchise. And yet, when confronted with systemic irregularities, it has responded with denial, deflection, and a demand for affidavits, as though accountability were optional. This posture not only undermines confidence in the institution but contradicts the spirit of constitutional jurisprudence, which has consistently held that free and fair elections are part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

The Representation of the People Acts (1950 and 1951) place exclusive responsibility for electoral rolls and conduct of polls in the Commission and its officers. Judicial precedent has repeatedly affirmed that responsibility cannot be outsourced: the acts and omissions of Booth Level Officers, EROs, or DEOs are legally those of the Commission itself. To suggest otherwise is to erode the very chain of accountability on which democratic governance depends.

The 2023 law granting Commissioners sweeping immunity from civil and criminal liability has only deepened this accountability gap. It insulates those at the helm of the electoral process even as field officials remain exposed. The effect is an inversion of constitutional principle: the higher the authority, the weaker the responsibility. This cannot stand in a democracy committed to the rule of law.

Beyond the legal terrain, the implications are starker still. Public trust in the ballot is waning. For voters whose names were deleted in Uttar Pradesh or whose constituencies in Maharashtra and Odisha saw implausible surges in turnout, disenfranchisement is no longer an abstraction but a lived experience. For minorities disproportionately targeted, the erosion of the right to vote amounts to an assault on equal citizenship. In the long run, the normalisation of such irregularities risks hollowing democracy into ritual without substance.

Yet, the crisis also presents an opportunity — a chance to rebuild electoral integrity on firmer foundations. Transparency must be restored through machine-readable rolls, independent audits, and access to election records. Judicial review must strike down or narrow the immunity clause. Parliament must exercise oversight, and voters must be armed with enforceable rights against arbitrary exclusion. Most of all, the Commission itself must return to the ethos of independence, humility, and moral courage that once made it one of the most respected institutions of the republic.

India’s democratic journey has been extraordinary, not least because it defied global scepticism that universal suffrage could take root in a poor, diverse, postcolonial society. That achievement must not be squandered. At this juncture, the question is stark: will India’s elections remain the world’s largest exercise in democratic consent, or will they slide into a managed ritual shorn of credibility?

The answer depends on whether the Election Commission of India can reclaim its role not as a passive coordinator but as the constitutional sentinel of the people’s sovereignty. For in the end, elections are not about parties, politicians, or even governments. They are about the citizen’s simple, sacred act of marking a vote — secure in the knowledge that it counts, that it matters, that it cannot be stolen. To preserve that faith is to preserve the republic’s very soul.

Related:

A Satirical Imperative Request (SIR) to the CEC of India

Major Irregularities in 2024 Maharashtra Vidhan Sabha Polls; Vote for Democracy