“Segregation not only harms one physically but injures one spiritually. It scars the soul. It is a system which forever stares the segregated in the face, saying you are less than. You are not equal to.”

– Martin Luther King Jr

Poor access to public services like ready piped water and sewage facilities marks the areas where both Dalits and Muslims are relegated to live. This is especially true in Indian cities.

A recent study exposes this distressing reality of residential segregation and stigma faced by Muslims and Dalits in Indian cities. It argues that segregation ends up relegating marginalised Muslims and Dalits to areas with poor access to public services like piped water and sewage facilities, bringing these groups to the brink of precarity and maintaining their presence at the bottom of the hierarchy. These latest findings align with previous research demonstrating the prevalence of segregated living based on caste and religious identity in urban Indian cities.

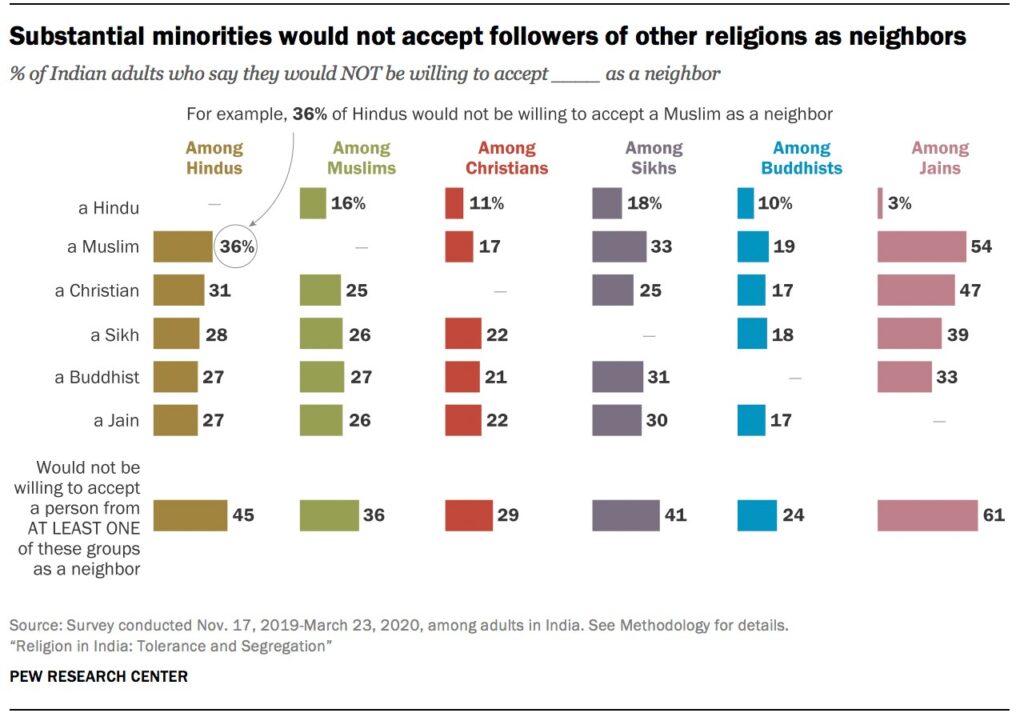

While Dalits continue to suffer a historical prejudice and cruel exclusion, for Muslims the past four decades have seen the slide. A recent Pew research exposes the distressing reality that while 45 % of Hindus show an openness to have neighbours of all faiths, a worrying 45 per cent exhibit a preference for excluding neighbours of certain religions. Specifically, 36% of Hindus do not desire Muslim neighbours. The Pew research also reveals that most Jains (61%) are unwilling to have neighbours from at least one religious group, with 54% indicating their refusal to accept Muslim neighbours.

Now an international study conducted by Novosad and shared on twitter, conducted by renowned developmental economists gives us the startling reality of urban India’s ghettoisation. The recent study confirms earlier findings by the Sachar Committee in 2006 and work done by academics in 2018 and thereafter,

Soon after the post Babri Masjid-demolition driven targeted communal violence in Bombay in December 1992-January 1993, Teesta Setalvad’s field study, published in Communalism Combat mapped the impact of the violence on community insecurity and how Muslims were driven to find “safety” in certain neighbourhoods. See Their Bombay, Our Bombay, December 1993, Communalism Combat republished here.

The 2023 study has now found that religious and caste-based segregation in India is comparable to the levels of Black/White segregation currently observed in the United States. However, it is less severe than the peak levels experienced in the US during the 1960s and 1970s.

The study involved over 1.5 million urban dwellings in India, indicating that despite rapid urbanisation, caste and religious divisions persist, resulting in the segregation of marginalised communities and their limited access to essential services.

The study was conducted by five developmental economists from renowned institutions, namely Sam Asher from Imperial College London, Kritarth Jha from the Washington-based Development Lab, Paul Novosad from Dartmouth College, Anjali Adukia from the University of Chicago, and Brandon Tan from the International Monetary Fund—their collaborative efforts aimed to quantitatively measure segregation in urban areas of India. The findings of their research, compiled in a paper titled “Residential Segregation and Unequal Access to Local Public Services in India: Evidence from 1.5m Neighbourhoods,” were recently shared by Novosad on Twitter.

A significant percentage of India’s Muslims and Scheduled Castes (SCs) or Dalits reside in neighbourhoods where the majority population is of the same religious or caste group. This pattern of segregation is prevalent in both urban and rural areas, and the level of segregation is even higher for Muslims.

The study’s findings are consistent with other research that highlights the pervasive residential segregation based on caste and religious identity in Indian cities. Despite 75 years of independence, Muslims and Dalits continue to face the worst discrimination in urban housing, with limited signs of improvement. Both communities encounter prejudice and limited social and economic mobility. Additionally, the waves of communal violence have resulted in the ghettoisation of Muslims in riot-prone cities, irrespective of their social class, education, and status.

According to Massey and Denton (1993), extensive studies conducted using data primarily from the 1970-1980 decade revealed that African Americans in the United States faced a situation of near-apartheid. These levels of residential separation experienced by African Americans were largely unresponsive to improvements in their socioeconomic status. African Americans remained highly segregated even in metropolitan areas where they had relatively higher incomes and education.

The recent study by Novostad et al. proves that neighbourhoods predominantly inhabited by SCs and Muslims have limited access to government-provided public services compared to other neighbourhoods within the same cities. The Sachar Committee has also previously made similar observations regarding Muslims in India. Various essential services such as secondary schools, healthcare facilities, electricity, water, and sewage systems are consistently of inferior quality in SC and Muslim neighbourhoods. This disparity in service provision is extremely substantial, with one exception being the presence of urban primary schools, which are relatively more common in urban SC neighbourhoods but less prevalent in rural SC neighbourhoods and similarly both urban and rural Muslim neighbourhoods.

“Young people in SC neighbourhoods have systematically worse outcomes than those in non-SC neighbourhoods — but the difference is mostly explained by the economic status of their families. This does not rule out a negative causal effect of growing up in an SC neighbourhood on child outcomes, because those parent outcomes could themselves be caused by living in a bad neighbourhood. For example, parents might invest less in their house (lowering the value of the consumption control) if they lack security of tenure.”

Children growing up in SC and Muslim neighbourhoods face disadvantages compared to those residing in non-marginalized neighbourhoods within the same cities. This disparity holds true even for non-SC non-Muslim children residing in SC and Muslim neighbourhoods. For instance, a child growing up in a neighbourhood with 100% Muslim population can expect to receive two fewer years of education compared to a child in a neighbourhood with no Muslims. Similarly, children in SC neighbourhoods experience a slightly smaller educational disadvantage. The neighbourhood effect explains approximately half of the urban educational disadvantage faced by SC and Muslim children.

Research indicates that neighbourhoods with a higher concentration of Muslims or Scheduled Castes (SC) have poorer educational outcomes. For instance, 17-18-year-olds in neighbourhoods that are 100% Muslim have 2.1 fewer years of education compared to those in neighbourhoods with no Muslims. Similarly, SC neighbourhoods have an educational disadvantage of -1.6 years.

According to the authors, residential segregation has a significant impact on cross-group inequality in India, particularly for marginalised social groups such as Muslims and Scheduled Castes. These groups face barriers in accessing public services and experience educational disparities, highlighting the need for addressing residential segregation and its consequences.

In a paper titled “Fractal Urbanism: City Size and Residential Segregation in India” (2021), authors Naveen Bharathi, Deepak Malghan, Sumit Mishra, and Andaleeb Rahman concluded that caste-based residential segregation is prevalent even in India’s most urbanised centres, with no significant variation based on city population size or growth over the past six decades.

One can observe similarities with the case of blacks in the USA, as the authors of the paper mentioned above argue that despite the ‘emancipatory promise of urbanisation’, Dalits and Muslims continue to face marginalisation as they are confined to neighbourhoods with inadequate access to public services. The findings suggest that even individuals belonging to elite or affluent backgrounds are limited to a few specific neighbourhoods, further reinforcing the pattern of segregation.

2018 Study confirms caste-based segregation

Furthermore, a research paper published in 2018 by three co-authors, Naveen Bharathi, Deepak Malghan, and Andaleeb Rahman, provided insights into caste-based residential segregation in specific cities. The study revealed that 30% of Delhi’s neighbourhoods, 60% of Kolkata’s, and 80% of Rajkot’s lacked any significant presence of Dalits and Adivasis. These findings underscore the alarming extent of exclusion experienced by marginalised communities in urban areas.

While the Census of India does not publicly release enumeration block data on religious lines, ongoing research by Naveen Bharathi indicates that Muslims face the highest levels of segregation in urban areas of Karnataka.

The promise of urbanisation as an emancipatory force has failed to materialise for Dalits and Muslims as their identities continue to shape their living conditions. Indian cities remain organised along caste and religious lines, undermining the notion of anonymity often associated with urban spaces.

Noteworthy scholars have explored the issue of residential segregation and the marginalisation of Muslims in Indian cities. For instance, Christophe Jaffrelot, a senior research fellow at CERI-Sciences, Paris, has discussed how the Disturbed Areas Act in Gujarat has been misused to prevent Muslims from mixing with other communities.

Gujarat’s Disturbed Areas Act

Jaffrelot has extensively studied the issue of urban segregation and the misuse of the Disturbed Areas Act in Indian cities. In his research, he explains that the Disturbed Areas Act, enacted in 1991, was originally intended to prevent distress sales and sales under duress in areas affected by communal riots. However, he points out that the state has wielded this law to restrict Muslims from mixing with other communities in major cities. The act allows Muslims to sell their properties to Hindus, but not vice versa, leading to the perpetuation of residential segregation.

In one of his writings, Jaffrelot highlights how the Gujarat government, prior to Narendra Modi’s tenure as prime minister, declared 40% of Ahmedabad as “disturbed” under the act. He also notes that in more recent times, the state government has classified new areas in Surat and Vadodara as “disturbed,” even though no riots took place there.

Thereby, cities in India exhibit significant levels of segregation, which is only slightly lower than in rural areas. In rural areas, neighbourhood composition is heavily influenced by the caste system, which has historically determined occupation and social status. In urban neighbourhoods, the religious and caste identities of residents strongly predict their access to public services and socioeconomic standing. Both Muslims and Scheduled Castes face high levels of segregation, but Muslims, in particular, experience greater challenges in accessing public services due to their segregated living arrangements. The rapid urbanisation in India has, to a large extent, replicated the caste and religious divisions observed in rural villages.

The Sanatana Dharma Parirakshana Trust

In 2014, the Sanathana Dharma Parirakshana Trust embarked on the development of an exclusive township, aiming to revive the traditions of the Brahmin community that were deemed to have diminished in modern India. The brochures promoting the township explicitly expressed the developers’ desire to “bring back the tradition of Brahmins” that they believed had ceased to exist in contemporary India.

Prospective buyers were required to complete thorough application forms, subject to scrutiny by the Trust, in order to purchase plots within the township. Notably, the Trust imposed a restriction that allowed plots to be resold exclusively to individuals belonging to the Brahmin community.

Concerned by these practices, K V Dhananjay, an advocate, and his colleagues lodged a petition with the Supreme Court, seeking legal action to halt these activities (which occurred in 2014).

Pew Research Centre

Pew Research Centre highlights the distressing reality that many Hindus (45%) exhibit a preference for excluding neighbours of certain religions. While a significant portion of Hindus claim openness to neighbours from all religious backgrounds, including Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, and Jains, an equal percentage (45%) express unwillingness to accept followers of at least one of these groups. Specifically, 36% of Hindus do not desire Muslim neighbours. The study also reveals that most Jains (61%) are unwilling to have neighbours from at least one religious group, with 54% indicating their refusal to accept Muslim neighbours.

Historically, cities in India had neighbourhoods with people of similar occupations and sometimes mixed religions. These neighbourhoods were self-governing, handling their own public services and even self-defence. Many neighbourhoods had limited entry points, leading to distinct boundaries between them. This structure continues today, resulting in segregated neighbourhoods.

However, modern-day residential segregation of marginalised social groups in poor neighbourhoods contributes to ongoing inequality between different groups. It has negative effects, such as increased discrimination in accessing public services, limited employment opportunities, and perpetuation of stereotypes. These disadvantages are difficult to address because segregation patterns persist over time.

Muslim neighbourhoods have increasingly become more concentrated due to safety concerns following Hindu-Muslim violence. These neighbourhoods are home to individuals from various social classes, with income segregation also existing within them.

Related:

Their Bombay, Our Bombay, December 1993

Film as Propaganda: the months between June 2023 & May 2024

Uttarkashi: Cross marks, “leave” threats on Muslim shops, hatred spreads to other towns: Uttarakhand

Love & Harmony over Hate: Int’l Day to Counter Hate speech, CJP’s unique efforts

CJP moves NCM against the repeated hate speeches by Pravin Togadia