Although the road ahead is a long one, the Supreme Court ruling in the Zakiya Jaffri and CJP case is certainly no victory for Narendra Modi

On June 8, 2006 when Zakiya Ahsan Jaffri, as-sisted by Mumbai-based Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP), filed a mammoth 119-page complaint supported by 2,000 pages of documentary evidence, little did she know – or really expect – that the Supreme Court of India would actually conduct an investigation under its watch through a Special Investigation Team (SIT) and thereafter ensure through a detailed order that her complaint would be treated as an FIR and a charge sheet also be filed. In the event that the SIT files a closure report, the petitioners’ right to a protest petition has been allowed.

The course of the Supreme Court-monitored investigations over a one-year period revealed serious lacunae in the functioning of the SIT, including the SIT chairman’s attempt at exonerating Narendra Modi. The chairman’s efforts were checked by the report of his own investigating officer (IO), AK Malhotra, and the independent assessment provided by the amicus curiae in the matter, Raju Ramachandran. After Ramachandran submitted his 10-page preliminary note in January 2011, the Supreme Court had, in March 2011, directed the SIT to reassess its own findings submitted 10 months earlier.

If nothing else, the verdict of the Supreme Court delivered on September 12, 2011 is a huge victory for the rule of law and for those of us who believe in due process and transparency and accountability in governance.

While not wasting valuable column space on the banal attempts by Modi and his party to give himself, and themselves, a clean chit, it is worth looking carefully at paragraphs 8 and 9 of the order (uploaded on the CJP website, www.cjponline.org) which clearly state that under Section 173(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC), the complaint – now to be treated as a de facto FIR – will, along with all relevant investigation papers, first be placed before a regular magistrate’s court and then, if so deemed, be committed to the court already hearing the Gulberg Society case. The task will be to file a substantive, expanded charge sheet against Modi and 61 others. What is more, according to the law, and a specific direction of the Supreme Court in this order, the complainants will be given a chance at every stage – in case the SIT baulks again, which is not unlikely, or the judge decides to exclude one or more individuals from among those named as accused – to be heard and carry their appeal right up to the Supreme Court.

The process will no doubt be arduous. And in the current climate where communalism and mass crimes do not commandeer national outrage as, say money matters in the 2G spectrum scam do, it will take every bit of effort to ensure that the battle, bravely fought, reaches an effective conclusion. For any one of the 20-odd magistrates before whom the SIT report/charge sheet could be placed, it will be a definitive test of independence and integrity.

Will a magistrate sitting in Ahmedabad be able to withstand the pressure, vitriol and vindictiveness of Modi’s administration? Difficult though it may be to keep the faith, at such a time we would do well to remember Judge SP Tamang, the Ahmedabad metropolitan magistrate inquiring into the Ishrat Jahan case, who, on September 7, 2009, submitted an exemplary report against all odds. The report indicted a number of police officers, including the then Ahmedabad police commissioner, for the murder in 2004 of the Mumbra-based teenager and three others that Modi and the central government had cynically made out to be hardened terrorists.

Contrary to popular belief, the Supreme Court verdict in the Zakiya Jaffri-CJP case exceeds the petitioners’ demands. While the now historic petition No. SLP 1088/2008 sought the registration of an FIR against Modi and 61 others, the Supreme Court order in fact goes several steps further, taking the criminal matter to the committal stage where cognisance will be taken, and prosecution begun, of the complaint.

Not surprisingly, the facts are at variance with the pernicious propaganda spread by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in this regard. Their views were unfortunately echoed on many of India’s television channels, raising questions about the media’s competence as well as its allegiances. Many in the broadcast media cheerfully announced a ‘clean chit’ for Modi early in the morning of September 12 and then tempered their telecasts as initial interviews with Tanvir Jaffri (son of Zakiya and the late Ahsan Jaffri) and Teesta Setalvad, and print interviews with amicus curiae Raju Ramachandran over the next few days, stated to the contrary. Far from being an exoneration of Modi and company, the recent judgement demonstrates that the apex court finds merit in the complaint and has now directed a lower court to take it forward as procedures allow.

The petitioners have never pleaded that the Supreme Court should directly indict Modi. They have never said and do not believe that anyone should be convicted without due process of law, hanged as they are so easily in RSS-desired Taliban-style kangaroo courts. They would also like to state for the record that they do not believe in the death penalty for anyone, not even a gun-wielding terrorist or a Narendra Modi who calculatedly employed all the resources at his command to paralyse his administration while murder stalked the streets. Apart from conspiracy to commit murder, other serious charges in the complaint include the deliberate efforts to doctor investigations through faulty registration of FIRs, the appointment of incompetent and ideologically biased public prosecutors, the destruction of evidence and terrorising witnesses into turning hostile.

All this and more is the subject matter of the criminal complaint filed in 2006. The only one of its kind in India, it is the first criminal complaint related to communal violence that goes beyond indicting individuals responsible for acts of violence to trace the outbreak of violence further, drawing links between the chief minister, his cabinet colleagues, leaders of empathetic political right-wing outfits and officials of the Indian Administrative Service (IAS) and the Indian Police Service (IPS) who bowed to the murderous designs of their political boss.

We must not allow ourselves to forget what Gujarat 2002 was about. Over 300 well-orchestrated incidents of violence spread across 19 of Gujarat’s 25 districts, the calculated murder of 2,500 innocents in reprisal killings, several instances of daylight rape, the destruction of Muslim-owned property worth Rs 4,000 crore and the destruction of 270 dargahs and masjids. Almost or just as bad as the violence itself is the deliberate subversion of justice, the destruction of evidence and the intimidation and influencing of witnesses.

The conclusion of the case so doggedly fought by Zakiya Ahsan Jaffri and Citizens for Justice and Peace will be a litmus test for the Indian system, to establish whether it has the courage to punish those responsible for some of its bleakest hours.

A unique trajectory

After the Gujarat police refused to entertain their complaint in June 2006, the petitioners moved the Gujarat high court for registration of an FIR against 62 persons and transfer of the investigation to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). The high court dismissed their petition in November 2007. However, the petitioners efforts were subsequently rewarded when the Supreme Court took cognisance of the case on March 3, 2008. A little over a year later, on April 27, 2009, the Supreme Court handed over the investigation not to the CBI but to the Special Investigation Team headed by former CBI chief RK Raghavan, which had been appointed by the apex court 13 months earlier to reinvestigate nine major Gujarat carnage cases.

In May 2009, Communalism Combat had, in its cover story ‘The Accused’, detailed critical elements of this complaint which was substantively different from that of the Gulberg Society case, one of the nine major carnage cases being reinvestigated by the SIT. Yet both the SIT and the state of Gujarat kept confusing the two cases. The primary distinction between the carnage cases and this complaint is the list of accused and the offences.

The accused in the complaint of June 8, 2006 (now treated as an FIR by the Supreme Court) are: the chief minister, Narendra Modi, 11 state cabinet ministers, three MLAs, three members of the ruling party in the state, three office-bearers and three members of extremist right-wing organisations and 38 high-ranking police officers and bureaucrats, beginning with the director general of police, Gujarat.

The progress of this case has been marked by high drama and behind-the-scenes subterfuge. However, it received scant attention until January 20, 2011 when the newly appointed amicus curiae, Raju Ramachandran, submitted a preliminary note to the Supreme Court which resulted in the court issuing directions to the SIT to reassess its findings. Until then, the media seemed uninterested in the proceedings, choosing to overlook the additional substantive evidence that the petitioners had regularly filed in support of their original complaint. The January 2011 order was the first sign that the SIT’s pathetic attempts to exonerate Modi and others from prosecution, in spite of the investigations carried out by its own IO, AK Malhotra, would not be accepted by the court.

Within days of the amicus curiae’s report being submitted to the Supreme Court and the court’s directions in the matter, Rahul Sharma, a serving IPS officer whose upright testimonies had allowed crucial evidence to enter the public domain, was served with a show-cause notice by a vindictive Narendra Modi-led Gujarat government. The notice was served on February 4, 2011. Sharma was later charge-sheeted on August 13, 2011 for speaking to the Supreme Court-appointed SIT and the state-appointed Nanavati-Shah Commission (now the Nanavati-Mehta Commission). It was Rahul Sharma’s deposition before the Nanavati-Shah Commission in 2004, when he made available a CD containing vital cellphone call records, that enabled CJP to analyse this data and place it before the commission and the courts.

Each hearing of this and related cases in the Supreme Court was punctuated by dubious attempts by the state of Gujarat and even the SIT to mislead the court and malign the petitioners – especially after October 2009 when CJP questioned the quality of the investigations being conducted by the SIT in the nine carnage cases. CJP secretary Teesta Setalvad was a specific target.

|

In a report to the apex court during hearings held in September-October 2010, the SIT mentioned a routine call made by Setalvad to the public prosecutor in the Gulberg Society case, RC Kodekar, who claimed that she had tried to threaten him. In January 2011, during the hearing of the matter pertaining to the carnage cases, the amicus curiae in that matter, Harish Salve, pointed out correspondence between CJP and the Geneva-based United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights on the threats received by senior advocate SM Vohra, counsel for the victims in the Gulberg case. Unfortunate observations by the bench on this matter attracted media publicity which worked to the advantage of a state responsible for mass crimes and determined to target those who stood up against it.

During this period a national daily was also used, on or about the date of every hearing, to project complete victory for the Modi government. On December 3, 2010, the date of the Supreme Court hearing in the Gujarat 2002 matters, as in January 2011, blatant efforts were made by an accused and cornered Gujarat government to manipulate sections of the media (‘SIT clears Narendra Modi of wilfully allowing post-Godhra riots’, The Times of India, December 3, 2010).

And yet, through 2010, when the SIT investigations were underway, it was reports in The Times of India and The Hindu that drew attention to the 15 phone calls made between the chief minister’s office/secretariat and the Ahmedabad police commissioner, PC Pande, between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m. on February 28, 2002, significant because they were made around the same time that the massacres at Naroda Patiya and Gulberg Society were taking place even as the police did nothing. CJP submitted detailed analyses of important phone call records to the Nanavati-Shah Commission in May 2010 (reported in Communalism Combat’s cover story, ‘Dial M for Massacre’, in June 2010) and to the Supreme Court in July 2011.

But finally, it was the exhaustive coverage by Tehelka magazine, which scooped the SIT report and contrasted this with evidence that CJP had gathered and submitted to the court, in two important stories (‘Here’s the smoking gun’, February 12, 2011, and ‘I was there. Narendra Modi said let the people vent their anger’, February 19, 2011), that impacted on the entire discourse. Television channels were now forced to look at the issues that Jaffri and CJP had raised over the past five years.

A subsequent report by Tehelka, ‘Whose Amicus is Harish Salve?’, in its March 12, 2011 issue exposed that the conduct of senior lawyer Harish Salve as amicus curiae in the Gujarat carnage cases gave rise to a conflict of interest. The story revealed that even while he was amicus curiae in the crucial mass murder cases before the Supreme Court, Salve continued to lobby the Gujarat government for projects for his wealthy corporate client, Eros Energy (Kishore Lulla). Incidentally, RK Raghavan, chairperson of the Supreme Court-appointed SIT, happens to be a corporate security adviser at a Tata company.

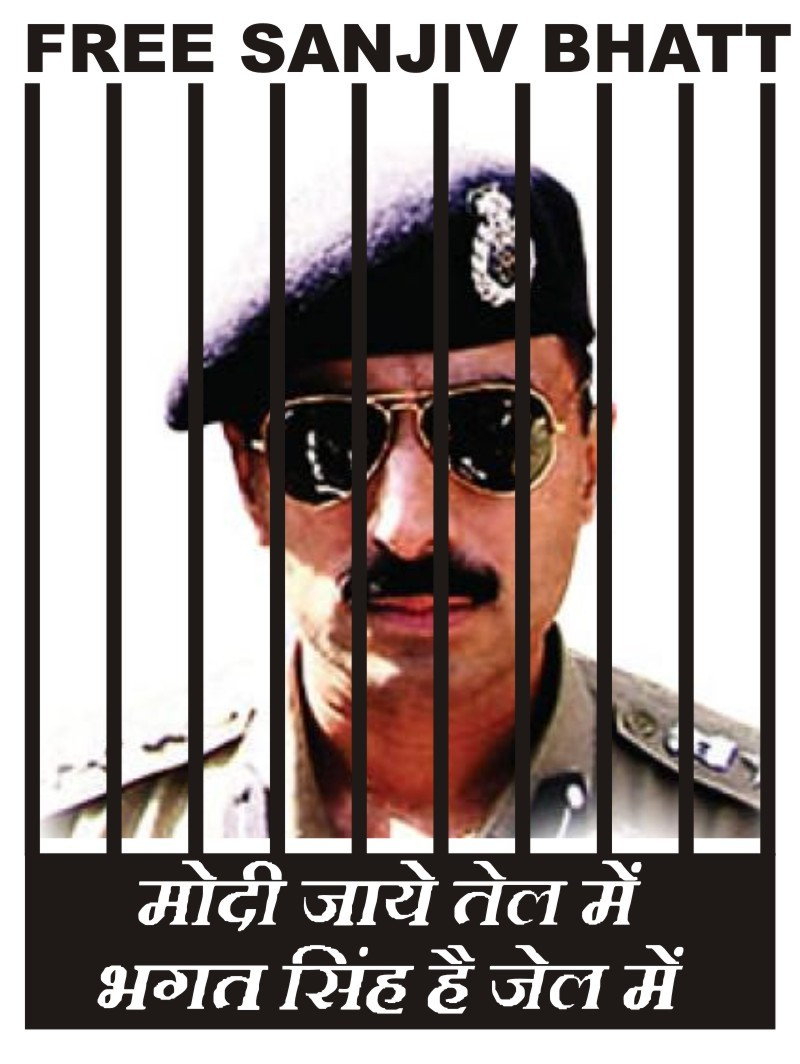

In April 2011 events took another dramatic turn as the much publicised affidavit of deputy inspector-general of police Sanjiv Bhatt, filed before the Supreme Court, drew widespread attention to the illegal instructions issued at a secret meeting held by Modi on February 27, 2002 – almost nine years after details of this meeting were first revealed in Crime Against Humanity, the report of the Concerned Citizens Tribunal – Gujarat 2002. In the affidavit, submitted directly to the Supreme Court registry and amicus curiae Raju Ramachandran, Bhatt detailed among other things how his testimony before the SIT in November 2009 and early 2010 had been leaked to the state government and led to intimidation from his superiors. This provided further confirmation of the petitioners’ suspicions about the conduct and integrity of the SIT.

In March 2011 the SIT had recorded a subsequent, formal statement from Bhatt under Section 161 of the CrPC. With this, Bhatt also submitted voluminous documents from the State Intelligence Bureau (SIB), including material that would prove that Modi was personally aware of the impending attack on Gulberg Society on the morning of February 28, 2002 when he deliberately did not intervene but instead allowed the mobs to attack former parliamentarian Ahsan Jaffri and others. After first informing OP Singh, Modi’s personal assistant (PA), Bhatt is stated to have personally informed the chief minister of the worsening situation at Gulberg Society.

Sanjiv Bhatt was suspended from service on August 8, 2011 and then charge-sheeted on September 18 even as Narendra Modi was fasting for ‘sadbhavna’, or communal harmony! On Friday, September 30, he was arrested on apparently trumped-up charges.

Doubts have been raised about the authenticity of Bhatt’s disclosures ever since his dramatic and relatively late appearance in public view. In response to this, we would like to point out that Sanjiv Bhatt was in fact cited as a witness by the petitioners in their original complaint precisely because his name figured extensively in the SIB records available to them.

Bearing testimony

Extracts from the complaint

List of witnesses:

1. KC Kapoor, in 2006, principal secretary, home; 2. Manoj D. Antani, in 2002, superintendent of police (SP), Bharuch; 3. AS Gehlot, in 2002, SP, Mehsana; 4. Vivek Srivastava, in 2002, SP, Kutch; 5. Himanshu Bhatt, in 2002, SP, Banaskantha; 6. Piyush Patel, in 2002, deputy commissioner of police (DCP), Vadodara; 7. Maniram, in 2002, additional director general of police (ADGP), law and order; 8. Vinod Mall, in 2002, SP, Surendranagar; 9. Sanjiv Bhatt, in 2002, SP, security, State Intelligence Bureau; 10. Jayanti Ravi, in 2002, collector, Panchmahal; 11. Neerja Gotru, in 2003, special investigating officer assigned to reopen investigations in some riot-related cases; 12. Rahul Sharma, in 2002, SP, Bhavnagar; 13. RB Sreekumar, in 2002, ADGP, intelligence.

In their complaint, the petitioners have also pointed out that Modi held several secret, undocumented meetings during that period at which many witnesses were present, who should also be examined and interrogated for information.

The superintendents of police in the districts of Mehsana, Banaskantha, Sabarkantha, Patan, Gandhinagar, Ahmedabad rural, Anand, Kheda, Vadodara rural, Godhra and Dahod, where mass killings were reported during the riots, all need to be specifically interrogated for their roles as also their failure to document illegal and unconstitutional instructions from the chief minister and other representatives of the state government.

Archived from Communalism Combat, Sept.-October 2011,Year 18, No.160 - Cover Story