There is a portentous rage in Sumeet Samos and he has successfully become one of the distinct voices in the Indian Rap music. Subverting the dominant cultural assumptions, Samos steers away from the mindless piecing together of words for the audience to just dance away to and, instead, carefully composes his work with a conscious political acumen, poetic sensibilities and his passion for languages. He presents the grotesque realities of our caste-ridden society, unnerving the audience, and holding a mirror to their complicity. Often, his music is unsettling and often sits heavy on the minds of his audience.

Hailing from the small village of Tentulipadar in the Koraput district of Odisha, Samos grew up in a segregated colony for the Doms, a schedule caste in India. On a quiet afternoon inside the Jawaharlal Nehru University campus, from where he is doing his M.A, Samos recollects the “enforced limitations” of caste hierarchies on him and his family’s lives. He firmly believes that these limitations cannot lead to a “starvation of his human expression.” He candidly remembers his journey, “I came to Delhi soon after my 12th board exams were over and was utterly confused about what to do next. I worked in call centers and gathered some money. One day I just came to JNU. I was nervous in the beginning, but I gave the entrance exam and was selected.” Now that he is a part of the JNU community, he recollects his memories of home in a new light. He now remembers the leaking thatched roof and the smell of kerosene from the lantern. He says that the rage of his poetry lies in contesting the way of life in the village, contending its romantic conception, and showing the goriness of caste that builds the tissue of relationships everywhere.

Samos, who is studying Spanish in JNU, considers language to be a fabric necessary to weave a powerful narrative of his experiences. Because of his socio-economic position, English as a language was not part of Samos’ education. However, he has converted his weakness into his strength and apart from Hindi and Odia, raps majorly in English. The average English-speaking crowd might find him exotic, but he does not fail to disorient them with his cumulative take on caste and class privileges, and the gigantic corporate networks that make them speak the way they do. His gradual mastery in the same is a marker of the beginning of a portentous moment of ‘writing back’ to the oppressors.

This ‘writing back’ is what Samos calls a “conscious rap” in which his words and ideas spring out from the ambedkarite anti-caste discourse that he as a member of the student organisation, BAPSA, has long been a part of.. His rap articulates class disparities, caste inequalities, religious dogmatism and violence, along with questioning the nationalist narratives. However, Samos’ work is only reassuring for the institutional Left in JNU until it calls them out on their limited understanding of caste. Samos’ work, thus is an insightful critique of the institutional Left in the premier university, stemming from the collective experience of being a Dalit. Recollecting the experiences of his BA days, he says, “A professor once asked if I came from Bermuda, because of the way I looked. I was not allowed to come up to the stage in most occasions, and I was systemically kept out of availing opportunities of scholarships to Spain despite scoring the best grades.”

He attacks the Indian Left in general and JNU in particular, about the missing caste understanding in their world view. He thwarts the overarching image of the Liberal University hailed by many, to show the otherwise unnoticed quotidian structural inequalities and deep biases against the Dalits built into it.

Samos’s critique is not only limited to the undoing of the caste hegemony of English language discourse. His composition in Odia uncovers the deep seated caste hierarchies of his home-state Odisha. He lashes out at the brahmana-karana (upper caste), ruling class of a predominantly dalit-adivasi state, and reveals the brutally disadvantaged position of the underprivileged communities because of the caste-class nexus between the bureaucracy, state and judiciary. He writes:

“. . .I am from

Koraput, the KBK

region

I am born in that

soil

my home is the dense

forest

I will write my own

History

I will roar like a

tiger

Just move aside your

mockery

I am a man of informed

consciousness

not just a being to inhale and

exhale…”

His “writing back” is an angry call for the reconstruction of a history that recognises their historical and cultural specificities instead of the all-encompassing, mainstream brahmanical history.

Samos also takes into account the gendered disparities that plague this endogamous hierarchical system of caste. His powerful symbolism of depicting the lives of subaltern women demonstrates how the most intimate aspects of one’s lives are shaped with tangible materialities of caste:

“…Their mothers in silk

sarees mine with

utensils…”

By pitting the higher caste-class group’s luxury against his miseries resulting from continued oppression, he leaves us uncomfortable, questioning and jilted.

Inspired by Childish Gambino’s This is America, that challenged the dominant ‘melting pot’ image of America by depicting gun-violence and racial injustice, Samos too, creates a strong counter-narrative with his rap—one that exposes the violent contradictions of the idea of a unified ‘society’ or ‘nation’ in our country through the symbols of quotidian objects of life.

Samos’ choice of rap music also has a historical relevance. Rap music had initially been an important tool of constituting history, as the Griots in West Africa show us. It was also a way of political advocacy and has always been a medium of subversion and resistance.

Religion is also an important aspect of Samos’ music and he lashes out at the insidious Hindu religion, in the same way that B. R Ambedkar once did by questioning the uncontested sanctity of ‘Lord Jagannath’ and uncovering the socio-economic repercussions of that Brahmanic liturgical control. In a daringly subversive act, he confronts the privileged Odia middle-class and shows them the “veritable chamber of horrors” that their religion is:

“…car festival, round eyes,

jagannath temple

a coconut in your hand and vermillion on

the forehead

this is what has chained the

society

this is how the priests have amassed

enormous wealth

they deprived you of all health and

comfort wake up from your sleep

alarmed…”

This constant engagement with his identity and negotiation with different spaces is how Samos’ poetry and music is born. He explains one way in which he understands his poetry, “There is a pattern to the way I write my poems: first, is to write about my experiences, second, about the institutions that led to those experiences and finally, a way out of those problems.”

In the last few years, Samos’ voice has been an important one, especially since the persecutions of Dalits have risen. Starting with the institutional apathy towards Rohith Vemula, to multiple mob lynchings, tyranny against minorities is on the rise. His resistance, however, has not been an easy one. He is often troubled and made to pay for his “indiscipline” by systematic bureaucratic methods: fines, withholding of degree, and suspensions, by the JNU administration.

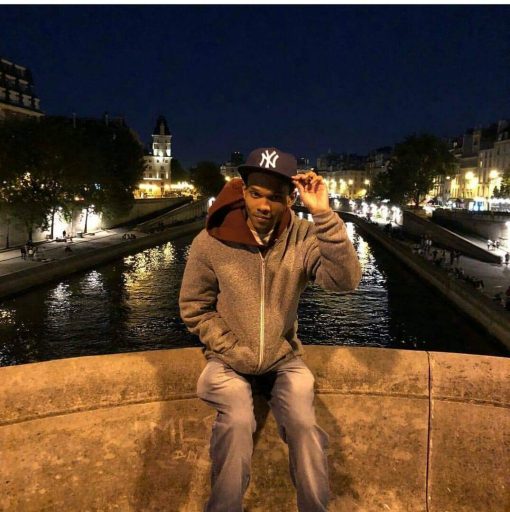

24 years old Samos hasn’t bowed down a bit. Upon his recent return from a Radio Live event in Paris, he has decided to pursue higher studies abroad. Samos is a poet of anger, one who is committed to chart out a space for the voices that were not cared for enough to be heard. It is this clarity that allows him to envision a future that Babasaheb once called for— a casteless society.

First Published on Indian Cultural Forum