Jaipur/Mumbai: The recent shedding of over 350,000 jobs in its automobile sector–and thousands elsewhere–is an indicator of the economic and social hurdles that jeopardise India’s demographic dividend, the growth opportunity afforded by the world’s second largest working-age population of 688 million people.

With unemployment at a 45-year high, poor health–42 infants per 1,000 still die before turning one–and low levels of education–an average person has attended school for 6.3 years–India’s demographic dividend is at risk, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of data from the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Indian government, and research from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI).

India needs state specific policies–good health and education systems, with more women entering the workforce in young states, and policies to attract migrants and elderly care systems in ageing states. India will also need to reduce caste and urban-rural inequality, especially in access to reproductive care, health, education and jobs.

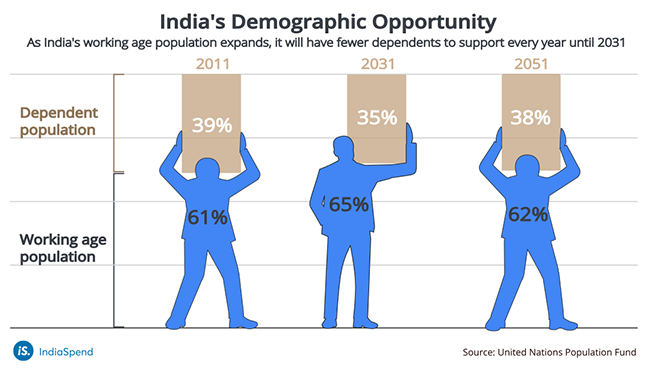

As its working population is larger than the population of dependents, “India, theoretically, could have a golden period in the decade of 2020 to 2040 (and continuing later, though with decreasing results)…but it could happen only if the right policies and programmes are put in place right now,” according to a 2018 paper by the UNFPA.

However, our research shows, states vary widely in the education, skill development and healthcare facilities they are able to provide, leading to varying employability outcomes.

As a result, states need policies specific to their unique challenges, which are determined, in part, by the stage of demographic transition they are in. For instance, the age-dependency ratio–the ratio of dependents (people below 15 years and above 64 years) to the working-age population (people aged 15-59 years)–shows that Kerala has an ageing population, while in Bihar, the number of working people will keep increasing until 2051, based on a 2017 UNFPA report, Demographic Dividend in India.

This story examines states’ disparate needs and offers some solutions. For instance, ageing Kerala would need policies to attract migrant labour from young states such as Rajasthan and Bihar, while relatively young states such as Bihar and Madhya Pradesh require strong health and education systems to prepare the workforce for the future.

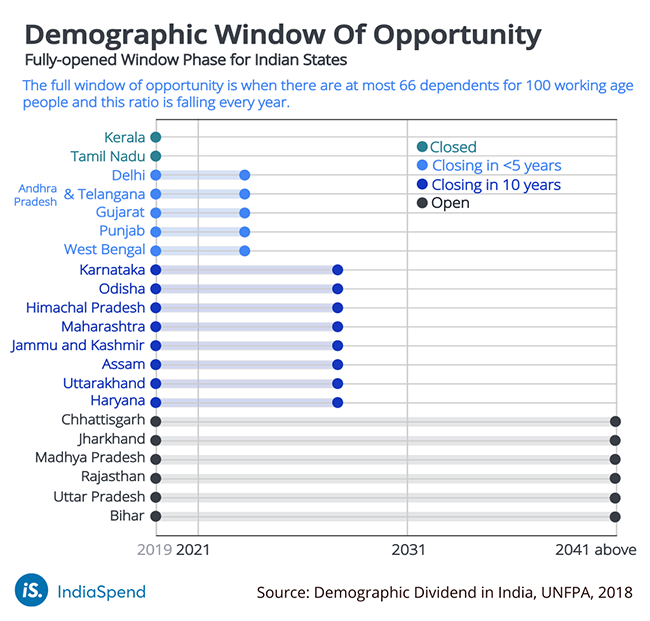

Window of demographic opportunity varies across states

The age-dependency ratio measures how many young people an economy has to support its children and the elderly. An expanding working-age population is associated with higher economic growth, according to a 2019 RBI study, based on how India’s population affected macroeconomic outcomes between 1975 and 2017.

This window of opportunity, which opened in 2005-06, can accelerate India’s economic growth and improve standards of living, at least until the working-age population starts declining.

Currently India’s average age-dependency ratio is low–with 67% of its population in the working-age bracket of 15-64 years, according to a 2018 UNFPA report. This is set to decline further and India, as a whole, will have a smaller dependent population and a larger working-age population every year until 2031, and a stable but reducing working population until 2041.

Because of the vast differences in fertility rates across states, India’s average working population only shows part of the story. If states are analysed individually, there are three broad patterns in India’s demographic transition, said Devender Singh, national programme officer at the UNFPA, based on research on the dependency ratio across Indian states. For the purpose of calculating states’ dependency ratio, the working age is considered to be 15-59 years, as 60 is the age of retirement in India.

“You cannot have the same sets of policies in all these sets of states,” to benefit from the demographic opportunity across India, Singh explained.

In states where the fertility rate is low, including some where the fertility rate is below replacement level–which means that the population will not replace itself–the window of opportunity of their working population will close soon.

In Tamil Nadu, New Delhi, Andhra Pradesh, Telnagana, Gujarat, Punjab and West Bengal, the window of opportunity will start closing after 2021, data from the UNFPA show. Kerala’s window of opportunity has already started closing.

In these states, the focus has to be on supporting the ageing population through better health facilities, and attracting more working hands from the states that have a labour surplus, Singh said. This might require programmes and policies to attract high quality labour from other states, and even re-training them to match the needs of the states with a low workforce.

The second group of states includes states such as Karnataka, Odisha, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Assam, J&K, Uttarakhand, Haryana, where the working age population is currently at its peak, but will start reducing from 2031.

There has to be a combination of policies for good health facilities for women and children, a good education system to prepare the workforce for future opportunities and a good health and support system for the elderly.

In the third group of states, which includes Uttar Pradesh (UP), Jharkhand, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh (MP), fertility rates are still very high, and these states have a high proportion of children. UP ‘s window of opportunity will start closing in 2043, Chhattisgarh’s in 2035, MP’s in 2041 and Bihar’s in 2051.

In these states, the focus has to be on providing good sexual and reproductive health services to women to meet family planning needs, and access to contraceptives. Women’s access to these services is indirectly related to the demographic opportunity. If women do not have access to good health services, and have a higher number of children, they might not join the workforce, reducing 50% of the population from the workforce.

The large child population would need very good quality education, health services, and good vocational training and skill development programmes to become the workforce of the future.

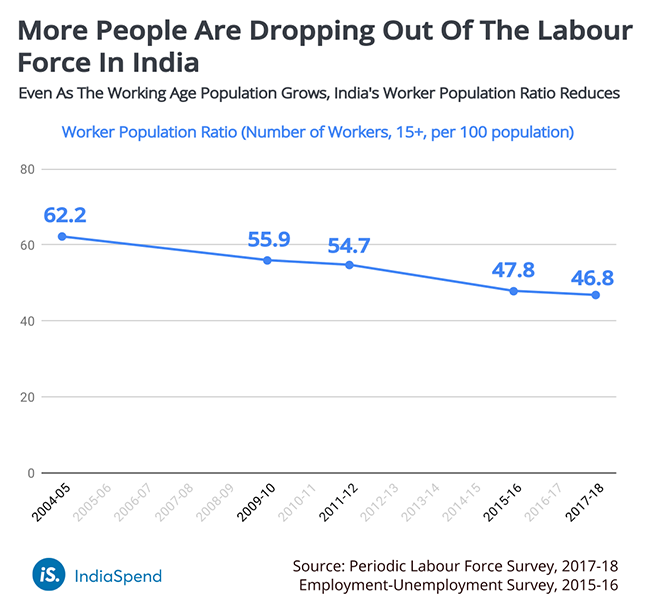

India’s reducing workforce and growing unemployment

Other countries have seen a high rate of economic growth during their period of low dependency. For instance, in the 10-year period starting 1985, when China’s dependency ratio was similar to India’s today, China grew at an average rate of 9.16% per year, data from the World Bank show. Similarly, South Korea grew at an average of 9.2% during a similar 10-year period in its demographic journey.

In the 10-year period starting when China was at a similar dependency ratio as India is today, the proportion of people, 15+yrs, in the labour force went from 78.6% to 73.3%.

But, in India, although the size of the working-age population is increasing, the number of people working is decreasing, the RBI study found. In comparison to China, India’s labour force participation, of people 15+ years, was 49.8% in 2017-2018, down from 50.4% in 2015-16, according to data from the periodic labour force survey, an employment survey conducted by the Indian government.

Between 2011-12 and 2014-15, the worker population ratio–the proportion of the workforce, 15+ years, in the total population–decreased from 55.9% in 2009-10 to 54.7% in 2011-12 and to 46.8% in 2017-18, data from the survey show.

A majority of this decrease came because of a reduction in the worker-population ratio of women from 22.8% in 2009-10 to 16.5% in 2017-18, data show.

High female unemployment

The number of people aged 25-64 years increased by around 47 million during the six-year period from 2014-15 to 2017-18, and 36 million, mostly women, moved out of the agricultural workforce, Himanshu (he uses one name), an economist wrote in Livemint on August 1 2019.

“The economy should have created at least 83 million jobs between 2012 and 2018 to accommodate those who have entered the labour force and those forced out of agriculture. As against these, the economy witnessed a decline in the number of workers by 15.5 million,” he wrote, based on data from India’s periodic labour force survey.

Out of those who are part of the labour force, 5.8% of males and 3.8% of females were unemployed in rural areas in 2017-18. In urban areas, 7.1% of males and 10.8% of females were unemployed, government data show. The unemployment rate has grown from 2011-12 when 1.7% of males and 1.7% of females in rural areas, and 7.3% of males and 5.2% of females were unemployed, data show.

“Whenever there are fewer jobs in the economy, women are impacted more than men, showing a gender preference in the Indian workforce, explained Singh of UNFPA.

IndiaSpend’s women@work series investigates some of the reasons for women dropping out of India’s workforce such as unequal burden of housework, unavailability of daycare for children, gender preference at the work place, sexual harassment, and family pressure.

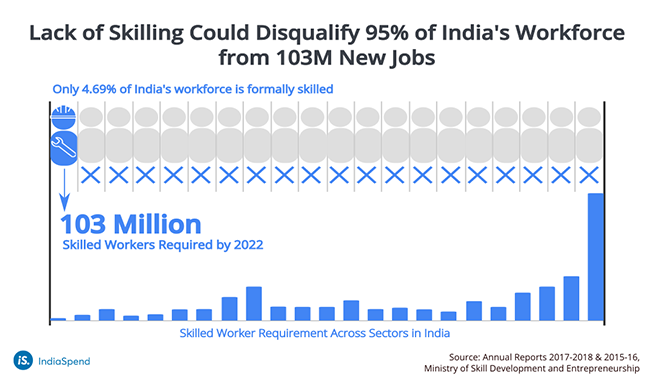

Indians need better education to qualify for jobs

One of the major issues for India’s poorly skilled workforce is the quality of education in India. For instance, in rural India, only 20.9% of children studying in Grade III in government schools could subtract, and only about half of the students in Grade V could read a Grade II level text, found the Annual Survey of Education Report 2018, published by Pratham, an education nonprofit.

India will have an incremental requirement of 103.4 million skilled workers within high-priority sectors such as construction, real estate and retail, between 2017 and 2022, estimated the Human Resource Requirement Reports, commissioned by the National Skill Development Corporation.

Currently, only 4.69% of the workforce has undergone formal skill training. A vast majority, 95.31% of the current workforce, could miss out on new jobs if they aren’t adequately skilled.

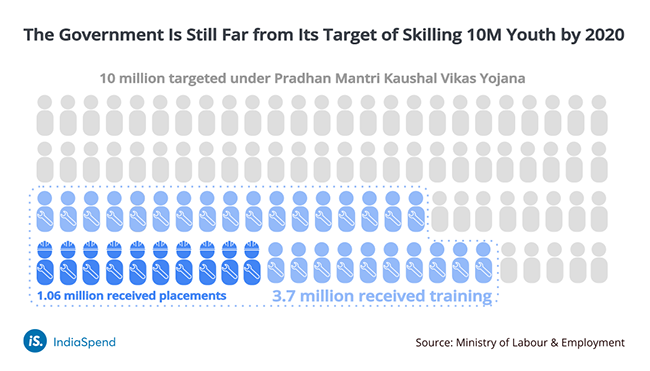

In order to provide training, the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship, under its Skill India Mission, launched a flagship scheme known as the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana 2016-20. With less than a year to go, only 3.7 million youth have received training under the scheme, despite a target of 10 million.

Further, 33% of those skilled, did not get jobs, according to an analysis of data from the government’s labour survey, published in Livemint in August 2019.

To use its demographic opportunity, India needs to reduce inequality between castes, urban and rural India

India could learn from other countries that have gone through these stages of demographic transition, and have better education and health indicators, but India has the unique advantage of learning from itself, explained Singh of UNFPA. States that still have high dependency ratios can learn from states which have passed that stage, especially as India has its own problems of inequality between castes and religion, rural and urban segregation, and poor public service delivery systems, Singh said.

For instance, the mean age of death for scheduled castes was 48 as compared to 60 for so-called upper castes, as IndiaSpend reported in April 2018. This suggests that India not only has to provide better health services to its population but reduce the caste-based inequality in accessing these services.

Similarly, there is a difference between fertility rates in rural (2.4 children, on average, per woman) and urban India (1.8 children, on average, per woman), data from the national family health survey 2015-2016 shows, which implies that, for more women to enter the workforce, focus on providing reproductive services to women would have to focus more on rural areas.

(Khaitan is a writer/editor and Ahmed is a Research Analyst with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend