The newsroom of The Searchlight in Patna, in the early 1980s, was a place haunted by legends. When I joined as Assistant Editor in 1980, the air was still thick with the memory of TJS George. Though his tenure as editor had been brief—a little over two years from 1963 to 1965—his impact was seismic.

The old-timers, from the chief sub-editors to the linotype operators in the printing section, spoke of him with a reverence usually reserved for mythical heroes. They would lower their voices, as if sharing a sacred secret, and recount tales of a man whose courage and conviction had not only defined the paper’s finest hour but had also reshaped the very landscape of Indian journalism.

I was only 27 then, younger than he had been when he took the helm. For the first forty-five days of my tenure, I found myself shouldering the responsibilities of the editor, R.K. Mukker, who was away in Punjab for his daughter’s wedding.

The weight of the chair felt immense, not just because of the responsibility, but because I was acutely aware of the giant who had occupied it before me. As a Malayali and, like him, a chain-smoker, my colleagues were quick to draw comparisons. “You remind us of George Saheb,” they would say, a compliment that was both flattering and daunting. It was an impossible standard to live up to, for I knew him only as a legend, a byline from a storied past.

This burgeoning curiosity compelled me to seek him out. During a leave trip to Kerala, I made a pilgrimage to the Indian Express office in Kochi. The office, perched near the coast, carried the distinct, briny scent of the sea and drying fish—a sensory detail that has remained etched in my memory.

I was nervous, expecting perhaps a brush-off from a journalist of his stature. Instead, I was met with immense warmth. He greeted me not as a stranger, but as a colleague from a shared alma mater. His memory was sharp; he inquired about old comrades from The Searchlight. We spoke of Thampy Kakanadan, the writer he had brought to Patna as an assistant editor, tracing his subsequent journey to Indian Airlines.

In that small, fish-smelling office, the legend began to transform into a person—approachable, articulate, and genuinely interested.

Inspired, I returned to Patna and wrote a long, reflective piece about him, which I promptly sent his way. He acknowledged it with a gracious thank you. Years later, when a brief biographical note appeared on Wikipedia, I felt a quiet pride seeing my article listed among the write-ups on him. It was a small, invisible thread connecting my journalistic journey to his.

Our paths crossed again many years later in Chandigarh. My editor, H.K. Dua, called me to his room to introduce a fellow Malayali. It was George. By then, we had been both part of the Indian Express family, he in the South and I in the capital, so the recognition was mutual. Our conversation turned personal.

I mentioned that my younger sister was married to a man from Thumpamon, and that the family had immediately pointed out a connection to him. I stumbled, trying to articulate the exact familial link. With a characteristic wave of his hand and a voice loud enough for Mr. Dua to hear, he clarified, “We are relatives, as are all Syrian Christians. If any two of them talk for two minutes, they will find they are relatives.”

It was a typical George remark—dismissive of trivialities, yet profoundly affirming of a shared cultural identity. He was returning from Himachal Pradesh and had dropped in on Mr. Dua, another link in the intricate chain of Indian journalism. That was to be our last meeting.

Yet, our intellectual engagement continued. Once, deeply troubled by his stance on a particular issue, I felt compelled to respond. Under the pseudonym ‘Bharat Putra,’ I penned an open letter to him, critiquing his position. I sent it off, half-expecting, half-dreading a fiery rebuttal. But silence was his reply. Perhaps he saw through the pseudonym; perhaps he believed the argument did not merit one. I never knew.

The stories of his time at The Searchlight, however, were his true monument. My colleagues would recount, with undimmed fervour, how under George’s leadership, the paper became the unflinching voice of the people. When students across Bihar rose in protest against fee hikes and soaring prices, The Searchlight stood with them, its coverage bold and uncompromising.

The defining moment came during a violent Patna bandh. Instead of retreating, George devoted the entire newspaper to a saturation coverage of the agitation. The presses ran overtime, and the print order soared past one lakh copies—a staggering, unprecedented figure for that era.

The establishment, led by Chief Minister K.B. Sahay, could not let this defiance stand. George was arrested under the draconian Defence of India Rules. What followed was a spectacle that entered the annals of journalistic folklore.

The eminent V.K. Krishna Menon, a national figure, air-dashed to Patna to personally argue for George’s bail before the High Court. The court premises swelled with a crowd never seen before, a sea of silent supporters bearing witness. George’s release was a triumph, marking him as the first editor to be arrested—and vindicated—in independent India. Even from his prison cell in Hazaribagh, the journalist in him could not be silenced; he authored a penetrating booklet on the student unrest.

The political cost for Sahay was severe; he was trounced in the subsequent elections in 1967 from both Patna and Hazaribagh. Overnight, TJS George was a national hero. Yet, his principled stand also spelled the end of his Patna chapter. The management, fearing further reprisals, had overruled his instruction to keep the editorial column blank until his release. For George, compromise was a language he did not speak, and he moved on.

His was a restless, visionary spirit. After his foundational years in India, which began under the tutelage of another remarkable Malayali, S. Sadanand of the Free Press Journal in Bombay, he looked east. In Hong Kong, he conceived and founded Asiaweek, a magazine modelled on TIME and Newsweek but with a crucial difference: an Asian soul.

In many ways, his magazine surpassed its American rivals in its nuanced, authoritative coverage of the continent. George’s reputation was now international. A shrewd businessman as well as an editor, he understood the economics of publishing. When he eventually sold the magazine, he secured not just his legacy but also his fortune.

His return to India saw him join the Indian Express as Editorial Advisor. When the group split and the southern editions became The New Indian Express, George was their pillar of strength. His stature was such that he was granted a unique privilege: his personal column ran on the front page, a boldface declaration of his importance.

Even more remarkably, he was permitted to take positions that sometimes diverged from the paper’s official editorial line—a testament to the immense trust and respect he commanded. From my desk on the edit page in Delhi, where we shared content with the southern editions, I would often notice this delicate dance of opinions. Readers adored him for his fearless candour, and his bosses knew better than to interfere. It was in these years that the newsroom, in a mix of affection and awe, began calling him the “Holy Cow of the Express.” He had a good command of Malayalam also.

His writing was as prolific as it was profound. His Handbook for Journalists became a Bible in journalism schools, shaping the ethics and craft of generations of reporters. As a biographer, he combined elegant prose with penetrating insight, producing acclaimed portraits of complex figures like V.K. Krishna Menon, the actress Nargis, his mentor Pothen Joseph, and the celestial vocalist M.S. Subbulakshmi. His scholarly works on Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore and the rise of Islam in the Philippines were extraordinary achievements, demonstrating a Malayali journalist’s ability to dissect foreign societies with rare authority and understanding.

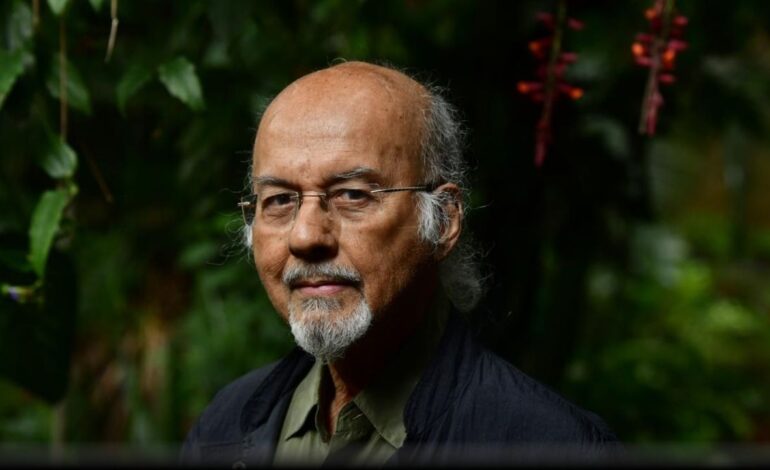

TJS George, who once wrote under the simple, powerful byline “GOG,” did not just practice journalism; he was its very embodiment. The saying goes that one has ink in their blood; for George, it was printing ink that coursed through his veins. He was not merely an editor; he was an institution—a beacon of intellectual courage, clarity of thought, and unyielding conviction.

Courtesy: The AIDEM