In India, the mainstream media is often critiqued for its alarming proximity to power. The term “Godi Media”—literally translating to “lapdog media”—has become a shorthand for channels that seemingly function as PR arms of the ruling establishment, eschewing rigorous journalism for cozy access and performative debates. The growing disillusionment with these traditional outlets has pushed a large chunk of the politically curious audience online, where YouTube creators, Instagram influencers, and Twitter personalities are carving out new spaces for information and influence.

Many have heralded this shift as a democratisation of media—a breaking down of the gatekeeping walls that allowed only a select few to shape the public narrative. Politicians now tweet their policy updates, address voters directly on YouTube, and make carefully curated appearances on influencer podcasts rather than press conferences. There’s even a growing belief that this new media, raw and seemingly more “authentic,” will shoulder the journalistic responsibility left vacant by legacy media.

But this belief deserves a pause, or at least a much cautious thought.

The truth is a large section of India’s new media creators are not journalists—nor do they claim to be. They are “content creators,” and that distinction matters. Of course, there are journalists on social media who are not solely content creators. Journalists like Ravish Kumar have been pushed out of the traditional media system and have found a way to do their journalistic content on social media. Channels like The Wire etc. produce news content with journalistic intent. This article is not about them. However, this article is about those creators on social media who engage with advertisers/sponsors and generate content including news content but do not call themselves journalists.

Take Samdish Bhatia, a widely popular YouTube figure known for intriguing and witty political interviews and videos of his travels across the country. He is articulate, progressive, and clearly influential. But even he does not identify as a journalist. He calls himself as a content creator. That is not a knock against him or his work. It is a recognition of the difference in mandate. Journalism, at its core, is about accountability—of those in power, of systems, of narratives. Content creation, however, is about engagement, reach, and often—neutrality that does not ruffle feathers. Truth be told, if people who call themselves journalists are not being held accountable as they should be, it is a rather hard task to hold social media content creators accountable.

And it is not just neutrality. Many of the most visible faces in the new Indian social media ecosystem are unabashedly capitalist and pro-market. Their discussions are less about the structural problems that plague India—such as homelessness, unemployment, agrarian distress—and more about how to “capitalize” on these contexts. So, while homelessness continues to plague millions, the conversations in popular podcasts revolve around real estate as an investment opportunity. Instead of interrogating inequality, there are video essays on personal finance, sponsored by a company or two.

This tone fits comfortably within the vision of a country aspiring to produce unicorn start-ups and billion-dollar tech moguls. Indeed, some of these billionaires have now become social media personalities themselves. Nikhil Kamath, co-founder of Zerodha, is a case in point. With little precedent, he was granted a rare, exclusive interview-podcast with the Prime Minister of India ahead of the Delhi Assembly Elections—a privilege rarely extended to even the editors of major TV news channels. Given Mr. Kamath’s power as a billionaire himself, he also did interviews with personalities such as Microsoft founder Bill Gates, New Zealand Prime Minster Christopher Luxon and Industrialist Kumar Birla.

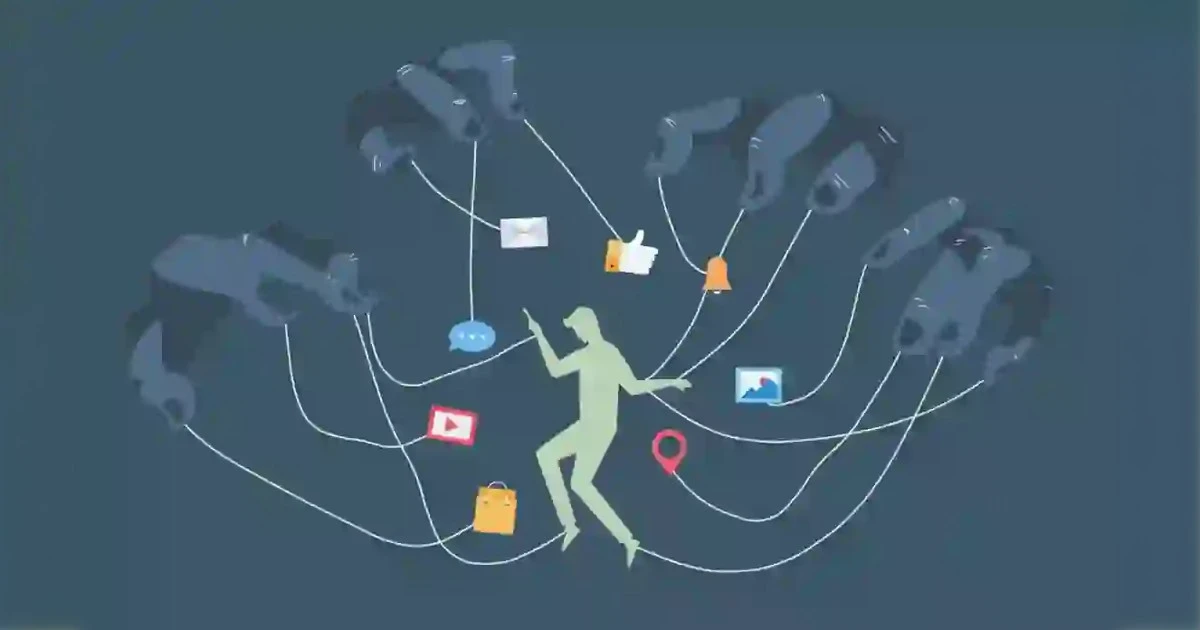

One must ask: when billionaires with government proximity become the popular voices of public discourse on social media, are we truly breaking away from “Godi Media,” or are we just replacing it with a new, glossier version that’s algorithmically friendlier and better branded? More importantly, will this new media ask the questions that the traditional media was supposed to ask or even attempt at creating ‘content’ around the issues?

Take Mr. Modi’s interview with Mr. Kamath for example. While discussing ideologies and idealism, Mr. Modi mentions Mahatma Gandhi and Savarkar in the same breath to remark that both had the same ideal of freedom with different paths. In an ideal world, this would have been met with another question about Savarkar’s credentials as a freedom fighter par Gandhi, or at least with a remark. What we get is Mr. Kamath continuing with next question as to what to do when someone trolls and how to develop a thick skin?

Or take another question about politics and money. The data on electoral bonds came out in 2024 but Mr. Kamath could not ask the question, at least on what Mr. Modi thinks of electoral bonds. Instead, he asks about how to facilitate youth entering politics given the huge amounts of money it takes to be in politics!

There’s also another curious and worrying trend: prominent intellectuals and creators within these spaces who align with the ruling ideology often criticize the opposition or even level attacks against dissenters with unchecked impunity. An advocate, who is one of the most popular voices on social media, aligned with the views of ruling establishment was asked on ‘The Ranveer Show’— “3 Indians that should leave India and never return are?” and the advocate said the names of news presenter Barkha Dutt, Professors Irfan Habib and Romila Thapar. The show’s host was the news cycle’s recent villain Ranveer Allahbadia. To keep up with the illusion of a critical and engaging podcast, the host asks “Why?” only to have the advocate say that these three have harmed Indian interests in their own ways and that they have done grave injustice to facts, truths and integrity. In the interest of critical engagement, one would expect the host to ask “How?” but he comfortably moves on to the next question.

This tells us two things. One, it was a bizarre question tailored to get a certain provocative answer. Two, it was not asked to critically engage with it. It was merely done to be performative

The bar for evidence is low. The responsibility to inform is often secondary to the need to perform.

Ranveer Allahbadia and another content creator Raj Shamani were some of the selected content creators who were given the opportunities to do interviews with union ministers like S. Jai Shankar and Nitin Gadkari. They were also attendees—Raj Shamani being the creator to introduce Mr. Modi, Ranveer Allahbadia being the recipient of the Disruptor of the Year Award—at the National Creators Awards organised in March 2024, just before the 2024 General Elections. Raj Shamani also hosted Arvind Kejriwal for an interview before the Delhi Elections.

This is not an allegation of social media creators selling space on their platforms to the government. There is no indication as of now. However, it is an observation of how close they are willing to be with power and how that hampers their capacity to be neutral, and courageous enough to ask questions, engagingly sharp ones if not tough ones.

This is also not a personal attack on these individuals. Many of them are intelligent, talented, and operate in good faith. But collectively, they form a media ecosystem that is, for the most part, timid when it comes to holding power accountable. And that makes them complicit—not by intent, but by design.

There is an imminent need to resist the temptation to confuse visibility with credibility. Just because a YouTube video racks up a million views or is made by a Billionaire does not mean it is accountable. Just because an influencer is articulate does not mean they are committed to the truth. Just because the production is slick does not mean the content is rigorous.

Social media is not journalism. It can include journalism, but it is not structurally bound to its principles. And in a country like India, where power is both opaque and muscular, the distinction between the two is not just academic—it’s existential for democracy.

So yes, we should celebrate the diversity of voices that social media enables. But we should also be wary—especially of the ones that get a little too close to power. Especially the ones that never ask hard questions. Especially the ones that call themselves everything—except journalists.

(The author is part of the legal research team of the organisation)

Related: