The Marxist philosopher, art critic and novelist, who passed away on January 2, popularised complex ideas and helped bring art into the mainstream.

Berger considered how through history and visual representation the male gaze has constrained women. John Berger's Ways of Seeing

The opening to John Berger’s most famous written work, the 1972 book Ways of Seeing, offered not just an idea but also an invitation to see and know the world differently: “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled,” he wrote.

Berger, who died on January 2 at the age of 90, has had a profound influence on the popular understanding of art and the visual image. He was also a vibrant example of the public intellectual, using his position to speak out against social injustices and to lend his support to artists and activists across the world.

Berger’s approach to art came most directly into the public eye in four-part BBC TV series, Ways of Seeing in 1972, produced by Mike Dibb and which preceded the book. Yet his style of blending Marxist sensibility and art theory with attention to small gestures, scenes and personal stories developed much earlier, in essays for the independent, weekly magazine New Society (between 1951 and 1961) and also in his first novel A Painter of Our Time, published in 1958.

The BBC programmes brought to life and democratised scholarly ideas and texts through dramatic, often witty, visual techniques that raised searching questions about how images – from European oil painting to photography and modern advertising – inform and seep into everyday life and help constitute its inequities. What do we see? How are we seen? Might we see differently?

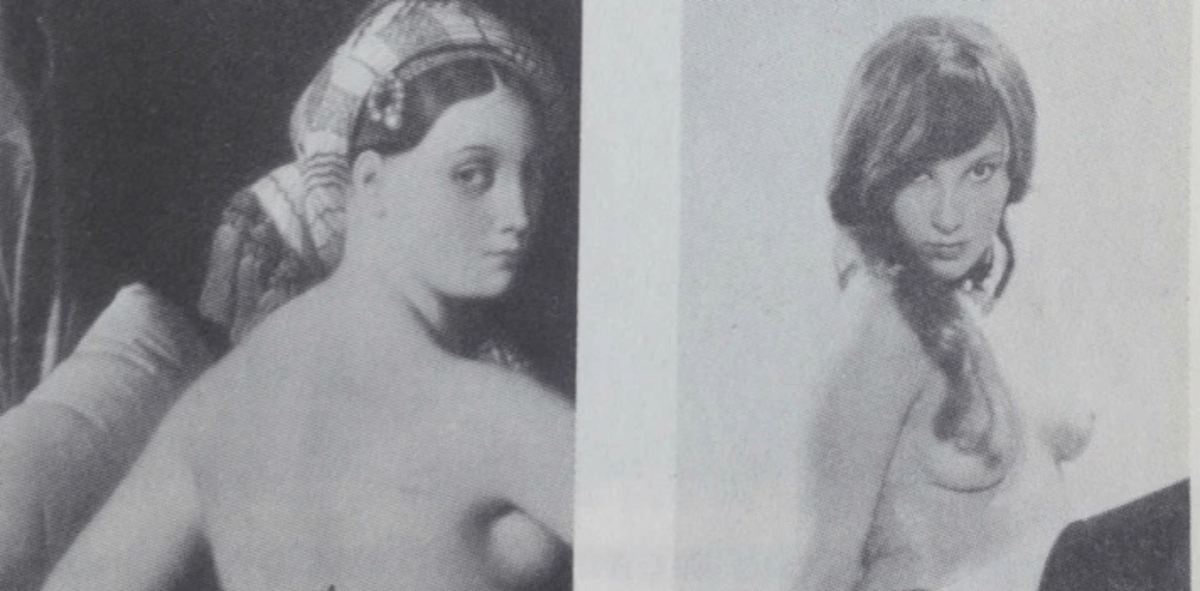

“Berger’s theoretical legacy”, the Indian academic Rashmi Doraiswamy wrote recently, “is in situating the look in the context of political otherness”. Berger’s idea that looking is a political act, perhaps even a historically constructed process – such that where and when we see something will affect what we see – comes across most powerfully in the second episode of Ways of Seeing – which focused on the male gaze.

Here Berger showed the continuities between post-Renaissance European paintings of women and imagery from latter-day posters and girly magazines, by juxtaposing the different images – showing how they similarly rendered women as objects. Berger argued that this continuity constrained how certain forms of femininity are understood, and therefore the terms on which women are able to live their lives. He identified a splitting of the European woman’s consciousness, in which she:

has to survey everything she is and everything she does because how she appears to others, and ultimately how she appears to men, is of crucial importance for what is normally thought of as the success of her life.

How we see

Historical context, scale, and how we see were recurring themes in Berger’s writing, films, performance and in his collaborative photographic essays with Jean Mohr, Anne Michaels, Tereza Stehliková and others.

Images need narratives to make sense. Verso books

Berger’s essays and books on the photograph worry at the political ambiguity of meaning in an image. He taught us that photographs always need language, and require a narrative of some sort, to make sense.

He also took care to differentiate how our reaction to photographs of loved ones depends on our relationship to the person portrayed. In A Seventh Man, a collaborative book with Jean Mohr on Turkish migrant workers to Germany in the 1970s, he put it simply:

A photograph of a boy in the rain, a boy unknown to you or me. Seen in the darkroom when making the print or seen in this book when reading it, the image conjures up the vivid presence of the unknown boy. To his father it would define the boy’s absence.

Under the skin

Because he had been a painter, Berger was always a visual thinker and writer. In conversation with the novelist Michael Ondaatje he remarked that the capabilities of cinematographic editing had influenced his writing. He identified cinema’s ability to move from expansive vistas to close-up shots as that to which he most related and aspired.

Click here to view video. Credit: The Conversation

Certainly Berger’s work is infused with a sensitivity to how long views – the narratives of history – come alive only with the addition of “close-up” stories of human relationships, that retell the narrative but from a different angle. For instance, writing about Frida Kahlo’s compulsion to paint on smooth skin-like surfaces, Berger suggested that it was Kahlo’s pain and disability (she had spina bifida and had gone through treatments following a bad road accident) that “made her aware of the skin of everything alive —- trees, fruit, water, birds, and naturally, other women and men”.

Self portrait. Frida Kahlo, CC BY-SA

The character in Ondaatje’s novel, In the Skin of a Lion, to whom he gave the name Caravaggio, was partly inspired by Berger’s essay on the painter. In that essay, Berger wrote of a feeling of “complicity” with the Renaissance Italian artist Caravaggio, the “painter of life” who does not “depict the world for others: his vision is one that he shares with it”.

Berger’s writerly inclinations and sensitivities seem to echo something of the “overall intensity, the lack of proper distance” for which Caravaggio was so criticised – and which Berger so admired. This intensity was not a simple theatricality, nor a search for something truer to life, but a philosophical stance springing from his pursuit of equality. He gave us permission to dwell on those aspects of our research or our lives that capture us intensely, and to trust that sensitivity. His was an affirmative politics in this sense. It started with a trust in one’s intuitions, along with the imperative to open these up to explore ourselves as situated within wider social and historical processes.

Reflecting on his written work, Berger wrote in the recent Penguin collection Confabulations:

What has prompted me to write over the years is the hunch that something needs to be told and that, if I don’t try to tell it, it risks not being told.

He knew very well that writing has its limitations. By itself, writing cannot rebalance the inequities of the present or establish new ways of seeing. Yet he wrote with hope. He showed us in his work and – by example – other possibilities for living a life that was committed to criticising inequality, while celebrating the beauty in the world, giving attention to its colour, rhythm and joyous surprises. We remain endowed and indebted to him.

(Yasmin Gunaratnam is Reader in Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London).

(This article was first published on The Conversation).