A shadow over elections

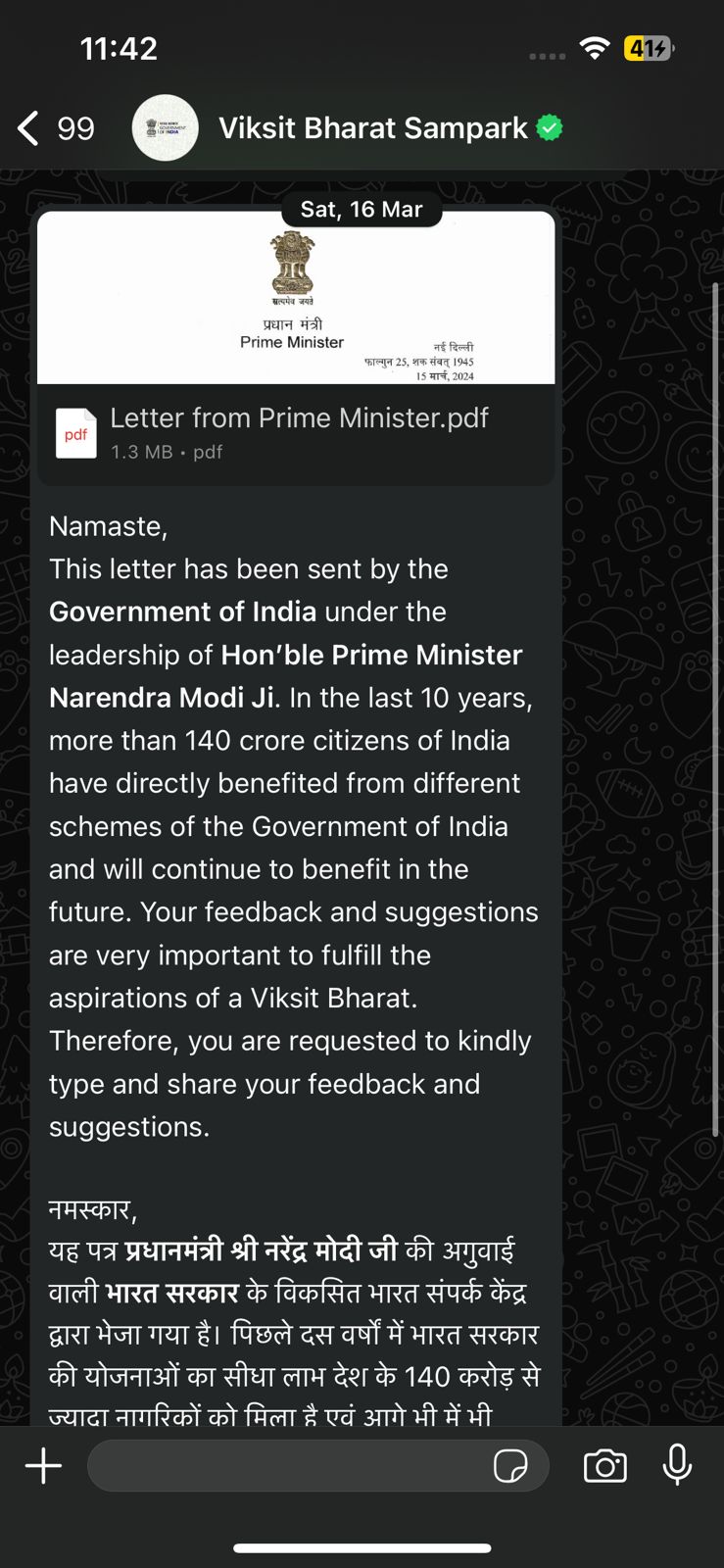

As the Lok Sabha election results loom large, a mass WhatsApp campaign has cast a shadow over the electoral process. Initiated by a business account named “Viksit Bharat Sampark,” the campaign has ignited significant debate and raised serious ethical and legal questions. This initiative involved the widespread dissemination of an open letter from Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in which he praised his government’s achievements and solicited public feedback. The messages were not only sent to millions of people in India but also reached citizens in Pakistan and the UAE, raising concerns about data privacy and the misuse of government resources.

The letter may be read here:

The controversial messages from “Viksit Bharat Sampark” were sent between March 15 and March 18, coinciding with the announcement of the Lok Sabha elections by the Election Commission of India on March 16, 2024. Some recipients reported receiving the messages as late as March 18 and beyond, exacerbating concerns about the timing and legality of their dissemination during the election period.

The WhatsApp messages, sent from a verified business account categorized as a “Public and government service,” aimed to publicize the Modi government’s initiatives and solicit feedback. The account identified itself as linked to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), Government of India. The letter, addressed to “My dear family member,” highlighted various government schemes and achievements over the past decade.

The use of “Viksit Bharat Sampark,” a business account on WhatsApp linked to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, raises serious questions about the misuse of government resources. This account utilized a paid service to send messages in bulk, a service permitted for government agencies but explicitly prohibited for political parties or entities engaging in political campaigning. Using government machinery for political campaigning undermines the integrity of the electoral process. This blurring of lines between government functions and political agendas is highly problematic.

Violation of the Model Code of Conduct

The Model Code of Conduct (MCC) is a set of guidelines issued by the Election Commission of India (ECI) to ensure free and fair elections. It prohibits the use of government resources for electioneering and mandates that parties in power should not misuse their official position for campaign purposes.

Clause VII(4) of the MCC states that “issue of advertisement at the cost of public exchequer in the newspapers and other media and the misuse of official mass media during the election period for partisan coverage of political news and publicity regarding achievements with a view to furthering the prospects of the party in power shall be scrupulously avoided.” The “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign, funded by government resources, violates this clause.

The campaign blurred the lines between governmental functions and political agendas. By using a government-linked WhatsApp account to send messages that promote the ruling party’s achievements, it appears to leverage official platforms for partisan purposes, which is against the principles of the MCC.

The opposition and the citizens have been vocal in its criticism, with leaders like Congress MP Shashi Tharoor and Manish Tewari highlighting the misuse of government machinery and data. They have called on the Election Commission of India to take action and ensure a level playing field. The Election Commission has responded by directing the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology to halt the campaign and sought a compliance report on the matter.

Will the @ECISVEEP take note of such a blatant misuse of government machinery and government data to serve the partisan political interests of the ruling party? pic.twitter.com/wrV6iWwfsJ

— Shashi Tharoor (@ShashiTharoor) March 18, 2024

.@ECISVEEP – This unsolicited WhatsApp message came at 12.09 AM today . It seems to be from @GoI_MeitY .

Is this not a blatant violation of the both Model Code of Conduct & Right to Privacy.Where did @GoI_MeitY get my mobile number from ? Which database are they unauthorisedly… pic.twitter.com/MDvOhHrYcb

— Manish Tewari (@ManishTewari) March 18, 2024

Upon receiving complaints about the “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign, the Election Commission of India took action to address the violations. The ECI directed the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology to halt the bulk WhatsApp messaging campaign immediately. The ECI emphasized that such actions compromised the level playing field necessary for free and fair elections.

Find the letter sent by the ECI to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology here:

The Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology was ordered to stop sending the bulk WhatsApp messages immediately to prevent further misuse of government resources. The ECI asked the Ministry to submit a compliance report detailing the steps taken to halt the messaging campaign and ensure adherence to the MCC.

While the Election Commission of India’s response was swift, it has not gone far enough to address the full extent of the violations and their implications:

- Halting the campaign and requesting a compliance report, while necessary, do not address the systemic issues that allowed the campaign to happen in the first place.

- The ECI’s actions did not hold specific individuals accountable for the breach. A detailed investigation into who authorized and executed the campaign, and appropriate punitive measures against them, are crucial to prevent future occurrences.

- The ECI did not address the breach of privacy adequately. The misuse of personal data for political campaigning is a serious violation that demands thorough investigation and stricter enforcement of data protection laws.

- This incident highlights gaps in the legal framework governing the use of digital platforms for political campaigning. The ECI should advocate for stronger regulations and enforcement mechanisms to govern the use of technology in elections.

The “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign has highlighted the blurred lines between governmental functions and partisan political activities. By using official channels to send messages that praise the ruling party’s achievements and using government resources, the campaign undermines the impartiality of the electoral process and raises doubts about the integrity of elections. This misuse of government resources for political gain not only violates the Model Code of Conduct but also threatens the democratic fabric of the country.

Data Privacy and Viksit Bharat Sampark

The long and short of the issue is unauthorized access to a vast database of phone numbers. MeitY used some database to send its messages, but there is a complete lack of transparency about how it was acquired or what database was use. This obscurity casts doubt on the legality and ethical implications of how the data was obtained. A crucial question is: how did MeitY acquire the vast database of phone numbers used for this unsolicited outreach? Did they get user consent before using this information[1]?

The possibility that MeitY acquired the data from another public or private entity opens a whole new can of worms. Were legal procedures followed during the acquisition of this database? Did the original source adhere to data privacy norms? A core principle of data protection is that personal information can only be used for the specific purpose for which it was collected. Reusing it for something entirely different, especially without consent, is a major red flag. MeitY facilitated this access without clear consent mechanisms from the recipients.

Further exacerbating the situation is the delayed enforcement of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDPA) and the exemption granted to government entities under Section 17(2)(a). This section allows the Central Government to issue a notification exempting any “instrumentality of the State” from the provisions of the Act in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, maintenance of public order, or preventing incitement to any cognizable offence relating to any of the above. This creates a legal grey area where the government has significant autonomy in data collection and usage, with limited checks and balances. The lack of strong regulations makes it difficult to hold the government accountable for potential breaches of privacy. With the ability to collect and process personal data without consent, the potential for misuse becomes a significant concern. This could involve political micro-targeting, where voters are bombarded with messages tailored to their preferences, potentially manipulating their choices and undermining the fairness of elections.

Ideally, a Data Protection Board should have established guidelines in advance of the elections to prepare for privacy-related infractions under the new Digital Personal Data Protection Act of 2023. Except the Data Protection Board would report to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, which is the body violating these provisions to send WhatsApp messages to everyone[2]. The BJP and the state apparatus have merged, with little distinction between party operations and official policy.

The absence of stringent restrictions on data usage under the current legal framework creates a worrisome prospect of unchecked data exploitation. The lack of clarity on the criteria for invoking exemptions under the DPDPA leaves room for interpretation, potentially leading to further misuse of personal data.

Moreover, the campaign has also violated the policy of WhatsApp. The WhatsApp Business Messaging Policy mandates that businesses obtain opt-in permission from recipients before sending messages. Clause 1 of the policy reads “You may only contact people on WhatsApp if: (a) they have given you their mobile phone number; and (b) you have received opt-in permission from the recipient confirming that they wish to receive subsequent messages or calls from you on WhatsApp[3].” However, in the case of the “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign, there was no evidence of such consent being obtained. This not only violates WhatsApp’s policies but also raises fundamental questions about the government’s respect for individual privacy rights.

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to privacy as a fundamental right. However, the actions of MeitY in using personal data for political messaging without consent undermine these guarantees. The campaign’s reach into countries like Dubai and Pakistan underscores the international scope of the privacy concerns, raising questions about the legality and appropriateness of such cross-border data usage.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign has exposed critical flaws in India’s data protection and privacy frameworks. The unauthorized use of contact information for political messaging, without explicit consent, is a clear violation of privacy rights and undermines democratic principles. As India moves forward, it is imperative to enact and enforce data protection laws that prioritize the rights and interests of citizens over unchecked governmental authority.

Upholding the principles of individual privacy rights is not just a legal obligation but a moral imperative in safeguarding democracy in the digital age. The delayed enforcement of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act and the absence of robust regulations create a fertile ground for data exploitation, particularly in the context of political campaigning. As citizens grapple with the intrusion into their personal space, questions loom large over the government’s commitment to upholding constitutional guarantees of privacy and freedom of expression.

In this digital era, the integrity of electoral processes and the protection of individual privacy rights must be preserved at all costs. The “Viksit Bharat Sampark” campaign serves as a stark reminder of the dangers of unchecked data usage and the urgent need for comprehensive data protection laws and regulatory oversight. Without these safeguards, the trust of citizens in democratic institutions and electoral processes will continue to erode, posing a serious threat to the future of democracy in India.

[1] https://internetfreedom.in/whatsapp-message-from-meity/

[2] https://www.barandbench.com/columns/inside-the-pms-inbox-privacy-politics-and-digital-governance

[3] https://business.whatsapp.com/policy

Related:

The Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2002 is harbinger of a surveillance regime?

A miss and a miss with the new Data Protection Law

United Against Hate: CJP’s Battle for a Hate-Free Election in 2024!

In Garb of Data Protection Bill, Centre Attacking RTI, Allege Information Commissioners

New data protection law comprehensive but full of exemptions