* Rudal Shah, arrested in 1953, remained in Bihar’s Muzaffarpur jail for 30 years despite being acquitted in 1968.

* Boka Thakur, arrested at age 16, was jailed and detained without trial for 36 years in Bihar’s Madhubani jail.

Shah and Thakur are examples of 282,879 undertrials in Indian prisons, according to Prison Statistics 2014, a number equal to the population of the Caribbean nation of Barbados.

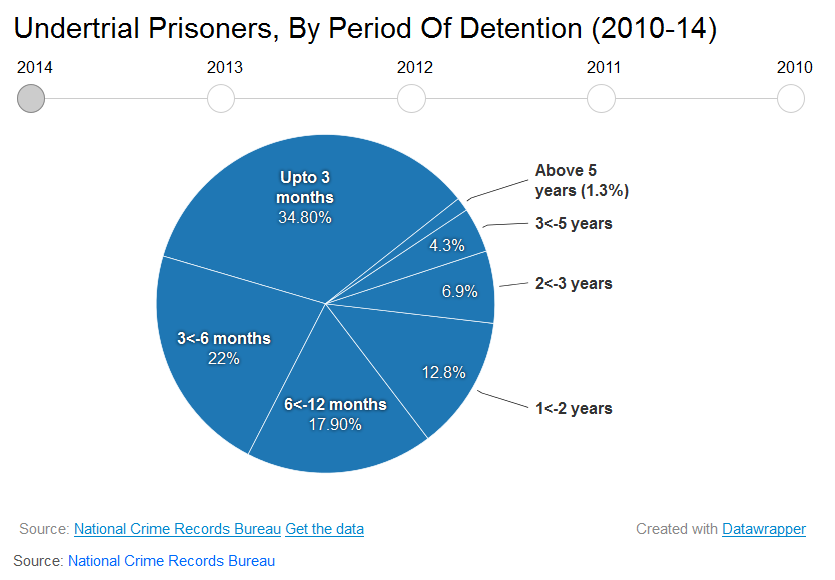

An IndiaSpend analysis of available data reveals the extent of the problem: Between 2010 and 2014, 25% undertrials had been jailed for more than one year. The percentage of undertrials to total prisoners has remained over 65% during this period.

In 2014, seven in 10 prisoners were undertrials, and two in 10 had been detained for more than one year without being convicted.

Undertrials—those detained in prisons during trial, investigation or inquiry—are presumed innocent till proven guilty. But they are often subjected to psychological and physical torture during detention and exposed to prison violence and poor living conditions. Many lose their family ties and, often, their livelihoods.

Undertrials tend to have restricted access to legal representatives for two reasons: Lack of resources and curtailed liberty to communicate with lawyers from within the jail premises. This is despite a 1980 Supreme Court ruling that Article 21 of the Constitution entitles prisoners to a fair and speedy trial as part of their fundamental right to life and liberty.

The court also pointed out that prisoners face a “double handicap”—most are poor, come from disadvantaged social groups, have little education, and their voices are rarely heard.

“The judiciary and the government have admitted that many undertrials are poor people accused of minor offences, locked away for long periods because they don’t know their rights and cannot access legal aid,” Arijit Sen, manager, undertrials project at Amnesty International, an advocacy, told IndiaSpend in an email interview.

Undertrials often remain behind bars for years despite the provisions of Section 436A of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) which came into effect in 2005. This section mandates the release, on personal bond with or without surety, of undertrial detainees who have been imprisoned for half the maximum sentence they would have received if convicted for the offence they are charged with.

This section does not apply to those who could be sentenced to death or life term. But 39% of those charged for crimes under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) couldn’t be punished with life term or death penalty, Prison Statistics 2014 show.

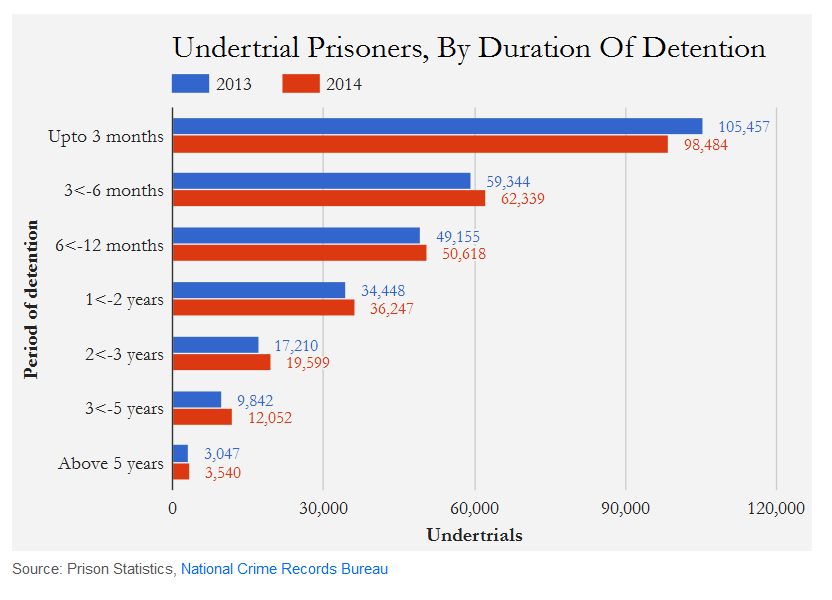

As many as 122,056 undertrial prisoners (43%) have been detained for more than six months to more than five years by the end of 2014. Many of them have remained in prison for more than the period of punishment they would have got had they been convicted.

Source: Prison Statistics, National Crime Records Bureau

Source: National Crime Records Bureau

J&K has the worst record for detention over one year

The number of undertrial prisoners in all detention periods increased over five years, except in the case of detention up to three months. The highest increase was seen in the category of detention for three-to-five years.

More than 25% of undertrial prisoners in 16 out of 36 states and union territories have been detained for more than one year in 2014. Jammu and Kashmir leads this list with 54%, followed by Goa (50%) and Gujarat (42%). Uttar Pradesh leads in terms of sheer numbers (18,214).

An attempt at reform

In June 2013, in a letter to the Supreme Court, former Chief Justice of India RC Lahoti had talked about how inhuman conditions persisted in 1,382 prisons despite a series of court and government orders.

In response to this letter, which was later registered as a public interest writ petition–and despite the lukewarm response from the states–the Supreme Court, in a landmark 2014 judgement, ordered the immediate release of undertrial prisoners eligible to benefit under Section 436A of the CrPc by establishing an Under Trial Review Committee (UTRC) in every district, recommended by a 2013 interim order.

A UTRC includes the district judge, district magistrate and district superintendent of police, collectively responsible for speedy trials and review of cases. “About 6,000 undertrial prisoners were released between July 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016. This is certainly a step in the right direction,” Sen said.

However, those released were 2% of undertrial prisoners in Indian jails. The pendency rate of IPC crimes–84% and 86% in 2014 and 2015, respectively–shows how slow the process of change will be.

Why the reform had little impact

One of the major causes of high pendency is vacancies in lower courts, IndiaSpend reported in December 2015. It would take a minimum of 12 years to clear 25 million pending cases in Indian courts, IndiaSpend had reported.

There is also little awareness among police and prison inmates about Section 436A of the CrPC. This section, which is a procedural mandate under CrPC, is often mistaken for an offence under IPC, according to Amnesty International.

Non-functional UTRCs, discrepancies in prison records, poor management of information systems, lack of effective legal aid and cancellation of trials due to shortage of police escorts and video conference facilities are factors that keep the number of undertrial prisoners in Indian jails high, reported Amnesty International.

(Alexander is a policy analyst with BOOM, an independent digital journalism initiative.)

This article was first published on India Spend