Much before the celebrations of the 150th year of the national song, Vande Mataram, on November 7, 2025, one of India’s leading music directors composed a song woven around the Vande Mataram tune (the album, Maa Tujhe Salaam). It was a song that was immensely popular. So, why the sudden focus on Vande Mataram and a debate in Parliament which saw accusations that words of the original song were muted to appease certain sections, and that all this amounted to a betrayal by the Congress?

The so-called ‘mutilation’ of the song — a line being peddled by the government of the day — was part of an official resolution of the Congress Party’s Working Committee (CWC) meeting in Calcutta on October 30, 1937. The CWC meeting had Jawaharlal Nehru chairing the session and almost all the big stalwarts which included Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Bhulabhai Desai, Jamnalal Bajaj, Acharya J.B. Kripalani (General Secretary), Pattabi Seetharamiah, Rajaji, Acharya Narendra Dev, Jayaprakash Narayan, and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose in attendance.

The sense of the meeting:

Though Mahatma Gandhi was not a member of the CWC, he was a special invitee and was finalising the working of the resolution which was moved by Rajendra Prasad (later, the President of India) and seconded by Sardar Patel (the Home Minister in independent India). The resolution was unanimous: “The Working Committee have given careful consideration to the question that has been raised in regard to the Congress anthem ‘Vande Mataram’. This song has a historic background and has evoked deep enthusiasm and powerful sentiment in the course of our struggle for freedom. It has thus acquired a unique place in the national movement. The Committee recognize the validity of the objections raised by Muslim friends to certain parts of the song. While the Committee have taken note of such objections in so far as it has felt justified in doing so, it is unable to go any further in the matter. The Committee have, however, came to the conclusion that the first two stanzas of the song, which alone have been generally sung on Congress and other public occasions, should be the only stanzas adopted as the National Song for the purpose of the Congress and other public bodies and functions. These two stanzas are in no sense objectionable even from the standpoint of those who have raised objections, and they contain the essence of the song. The Committee recommend that wherever the ‘Vande Mataram’ song is sung at national gatherings, only these two stanzas should be sung, and the version and music prepared by Rabindranath Tagore should be followed. The Committee trust that this decision will remove all causes of complaint and will have the willing acceptance of all communities in the country.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has indirectly targeted this resolution of the CWC in which even Sardar Patel was a part of. But has the Prime Minister realised that he has attacked a spectrum of national leaders, whose remarks on the song are being used selectively to try and score points?

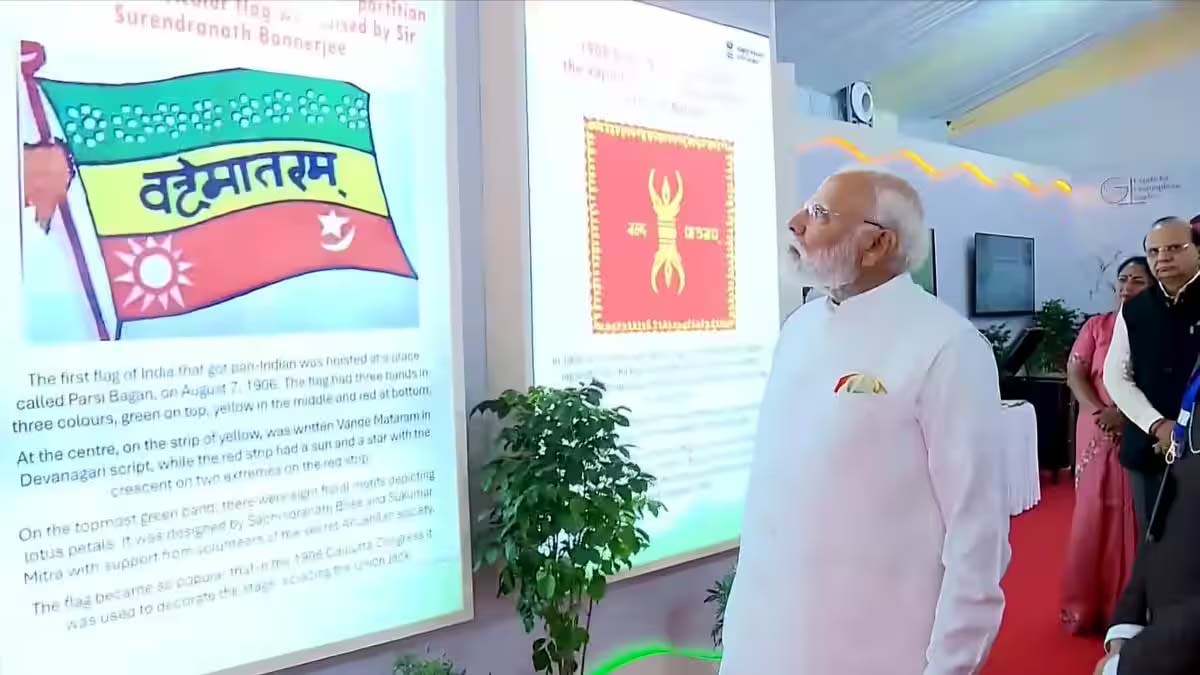

What was the purpose of debating this in Parliament? Was it to have a debate on the issue for the second time much after the one in the Constituent Assembly which sealed the issue? Composed by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Vande Mataram was first published in the literary journal, Bangadarshan, in 1875 and was sung at the 1896 session of the Congress by Tagore. All these exercises took place much before the partition of Bengal.

There is no doubt that the song became the spirit of all meetings of the national movement which also had substantial representation by Muslims also. It was in 1935, when the Government of India Act was enacted, that Indians got a chance to participate in the electoral exercise to get into Provincial Assemblies and the Central Legislative Assembly. The issue of participation in the elections held in 1937 had inner party repercussions. The Congress captured the Provincial Assemblies. Some were won by the Muslim League.

When the Congress entered the portals of power, it also had the duty to ensure a diverse culture and have Vande Mataram sung at government functions. The Calcutta session became the focal point to decide to have the edited version so that it would have a pan-India appeal. The song obviously had references to Hindu goddesses, but if one wanted to ensure the broader unity of religious groups, a basic understanding on its theme was essential. It was this pragmatic decision which made them contest elections in alliance and continue in the government for the next two years. In 1939, the Congress ministries resigned in eight provinces of British India.

Later, when the Constituent Assembly was convened and the interim parliament was doubling as the Constituent Assembly in 1947, it had 208 Congress members, 73 Muslim League members, and 15 others. It also had 93 members nominated from the princely States, giving it a total of 389 members. After Partition, and the departure of the Muslim League members from the Constituent Assembly, there were only 299 members — a majority of them from the Hindu fold. It will not be out of place to state that the entry of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar was possible when he was elected from Bengal Assembly by the Muslim League-dominated Assembly. After Partition, he could not continue and it was Nehru who made the decision to make the Bombay Governor nominate Dr. Ambedkar to the Assembly.

Making a choice:

The Constituent Assembly also had ideas of having a national anthem for the country. Members were made to listen to three important songs that were in contention — Vande Mataram, Sare Jahan Se Achha and Jana Gana Mana. Though secular in its meaning and set to a marching tune, Sare Jahan Se Achha was not picked as the lyricist, Allama Muhammad Iqbal, had become an ardent Pakistan supporter. Even after the final draft of the Constitution was adopted in 1949 in the House headed by Dr. Rajendra Prasad and two days before the coming into force of the Constitution, in 1950, Vande Mataram was sung in the House by a group.

However, Members were in favour of Jana Gana Mana, passing a resolution that it would be the National Song. The Constitution, which has 395 Articles, never referred to any national song as part of the constitutional framework. It was only in 1976, by the 42nd amendment, under Mrs. Gandhi’s tenure, that a provision was introduced for a fundamental duty under Article 51A (which also had a clause obligating every citizen to abide by the Constitution and respect its ideas and institutions, the National Flag, and the National Anthem).

It was later, under the Prevention of Insults To National Honour Act, 1971, that disrespect to the National Anthem was made a penal offence. The Supreme Court of India, in Bijoe Emmanuel vs State of Kerala, upheld the constitutional rights to freedom of religion and expression provided that actions do not disrupt public order or show disrespect to national symbols.

Despite being a Hindu majority, the Constituent Assembly selected Jana Gana Mana as the national anthem and was of the opinion that Vande Mataram would be the national song under its adopted version. It is against this background that one has to view the sudden ebullition over Vande Mataram with the request made by those in the ruling party to Members of Parliament to consider whether they should add a new fundamental duty under Article 51A, to accord the same respect to Vande Mataram as Jana Gana Mana.

In 2017, Justice M.V. Muralidharan of the Madras High Court gave a direction to the Tamil Nadu School Education Department that schools must sing Vande Mataram at least once a week, and crooned in offices once a month. Noting that the song could also be played in other government and private establishments at least once in a month, the judge said that if people felt that it was too difficult to sing it in Bengali or in Sanskrit, steps could be taken to translate the song into Tamil.

The Delhi High Court asked the Government of India to treat Vande Mataram on a par with the National Anthem. What is curious is that it was the same Narendra Modi government that told the court that both the National Anthem and the National Song had their sanctity and deserve equal respect. However, it said that the subject matter of the proceedings could never be a subject matter of a writ. The Modi government defended its position in court against granting equal legal status to the National Song as the National Anthem by citing the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971, which specifically criminalises disrupting the anthem but lacks a parallel provision for the National Song, highlighting the legal distinction.

A deeper reading:

The new controversy being sought to be created now over the National Song, 75 years after it was settled down by the Constituent Assembly, makes one doubt the intentions of the the present government. Is there an agenda to replace the National Song by a simple resolution of Parliament akin to the similar exercise done to cancel the special status of Jammu and Kashmir?

The amount of importance and publicity being given now to a non-issue certainly makes one to believe that it could be the next move of the Narendra Modi government — which is to bring in a different National Anthem for the country without disturbing the Constitution of India and any law to the contrary.

(The author, K. Chandru is retired Judge, Madras High Court; this article was first written for and published in The Hindu on December 11, 2025 and is being reproduced here with permission from the author)

Related:

Those Not Chanting Vande Matram have no Right to Live in India’: BJP MLA Surendra Singh

Activists singing Vande Matram called ‘anti-national’, attacked in Bihar!

The Politics of Processions: How the Sanatan Ekta Padyatra amplified hate speech in plain sight