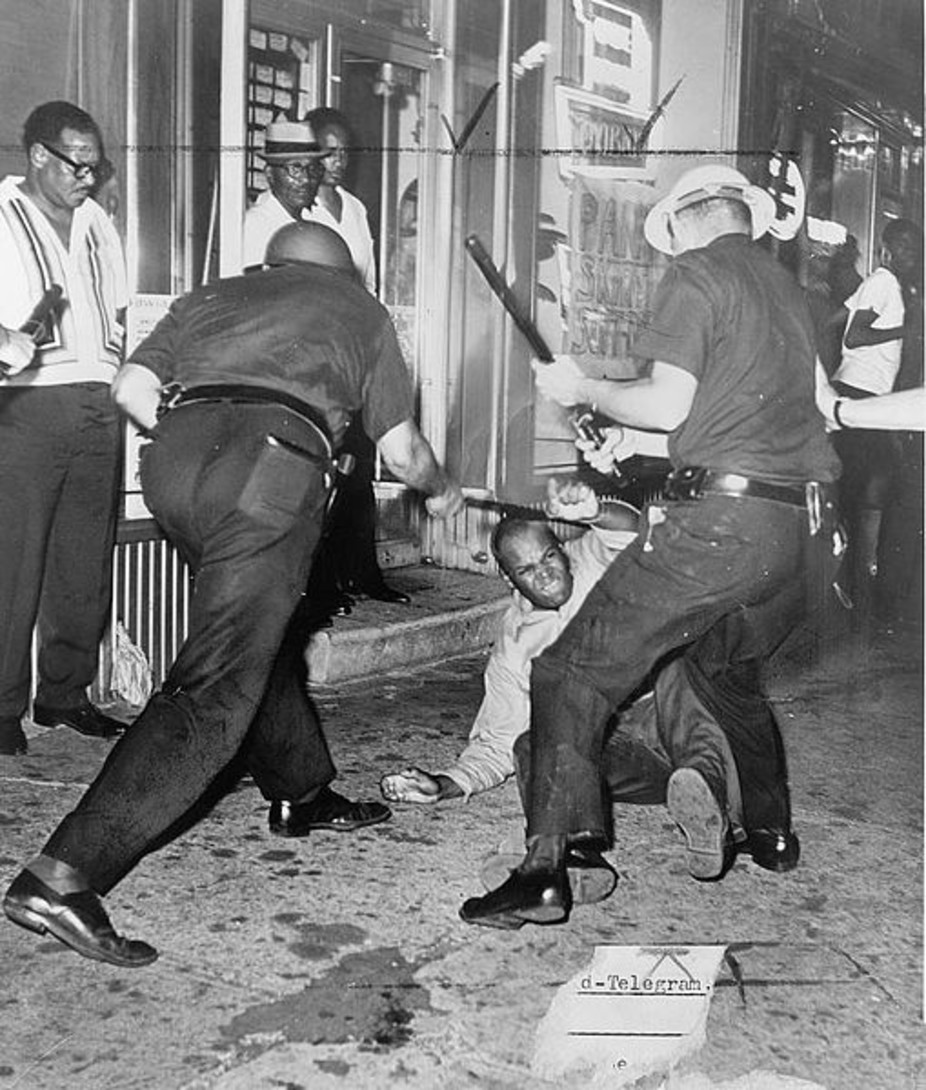

Riots in Harlem, 1964. Wikimedia Commons

After the killing of five police officers in Dallas last week by a lone gunman, where does the Black Lives Matter movement go?

Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza answered this question, saying she anticipated that the Dallas shooting would “create the conditions for increased security, surveillance and monitoring of protesters … an expansion of the police state, rather than reduction of one.”

As Garza points out, the failure of the dash cam and body cameras to document what happened in the killing of Alton Sterling in Louisiana highlights the limitations of technology as the centerpiece of reform. It had even been the focal point of Al Sharpton’s 2014 National March Against Police Violence.

As Garza argued, “There has to be something bigger than that.”

As a scholar of 20th-century African-American history and social movements, I have focused my research on community activism in the 1950s and 1960s against police brutality in major cities such as Los Angeles and New York. Police violence often opened a space for organizing people of color from across the religious and political spectrum around core issues facing their communities. But these coalitions were often tenuous. And the idea of police reform being the most important issue within the larger black freedom struggle has always been contentious.

The challenge facing us now is twofold. First, how can we think about addressing the problem of racialized police violence beyond professional and mechanical reforms?

And second, how can the national spotlight on police brutality be used as an opportunity to make broader changes that answer the fundamental question posed by Black Lives Matter: What does it look like to value black life?

The challenge of black unity

This tension was at play more than a half-century ago in a brief coalition formed in Harlem called the Emergency Committee for Unity on Economic and Social Problems. The organization was founded in the summer of 1961 by civil rights and labor organizer A. Philip Randolph.

Philip Randolph. Library of Congress/Gordon Parks

The group was originally formed to protest housing discrimination and the rise of unpoliced drug use in Harlem. The committee represented a wide swath of the Harlem activist community, including national civil rights figures like Bayard Rustin and black nationalists such as Lewis Michaux, “Pork Chop” Davis and Malcolm X.

The Emergency Committee for Unity on Economic and Social Problems was built on the premise of black unity around three action programs: unemployment, housing, and law and order enforcement. The Pittsburgh Courier immediately hailed it as a “beacon of light for other communities.”

But just months after its founding in August 1961, the subcommittee on law enforcement resolved to disband if the Emergency Committee for Unity on Economic and Social Problems would not focus on the issue of police brutality. Among the subcommittee’s recommendations were a civilian review board that would include representation from the community, a greater representation of African-Americans and Puerto Ricans within the police department and intensive human relations training on race within the police department.

By the following year, these and other political divisions led to a fracturing of the committee. Randolph turned his focus to organizing the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom at which Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. However, the march only loosely touched upon calls for police reform and marginalized both women and black nationalists from its program. Instead, it focused on ending school segregation and job discrimination, establishing a nationwide minimum wage and public job training, and enforcing the 14th Amendment to protect the voting rights of southern blacks.

Meanwhile, Malcolm X had moved to Los Angeles following a case of police violence which left one Muslim man dead and another paralyzed after an attack on the Nation of Islam’s mosque. No officers were indicted, and 14 men were charged with assault and resisting arrest, nine of whom were eventually convicted.

Police reform

Los Angeles was rife with discrimination and accounts of police brutality in communities of color. In 1962, the NAACP published a 12-page report documenting 10 major cases of brutality in the city. Roy Wilkins had even compared the police in Los Angeles “next to those in Birmingham, Alabama.”

Yet, the Los Angeles Police Department maintained a national reputation as one of the modern exemplars of policing during the 1950s. Meanwhile, the ACLU and NAACP had been fighting for police reform in Los Angeles for over a decade, including repeated calls for a civilian review board.

In part, Police Chief William Parker’s vision for a modernized police department appeared to reflect those called for by community activists, then and now. This included human relations training and a more diverse police force serving in these communities.

But Parker’s understanding of “diversity” was that everyone could be a “minority group member… any of which can be, and often has been discriminated against.” Training bulletins even illustrated this concept to police officers by showing them how it would feel to be called by derogatory phrases such as “fuzz” and “cop.”

Professionalization meant training police officers to eradicate racist ideas through practice. As Parker proudly told a police chief conference in 1955:

“Intolerance has become a victim of enforced order – habit has won out over belief.”

Modernization meant using empirical data to justify racist outcomes. The heavy use of police in communities of color, he explained, was simply “statistical – it is a fact that certain racial groups, at the present time, commit a disproportionate share of the total crime.”

Beyond police reform

Policing in Los Angeles became even more emblematic of the modern police state after the violent arrest of a young black man led to the Watts uprising in 1965. The sheriff’s department demonstrated the use of helicopters during the rebellion, and in turn earned the largest Office of Law Enforcement Assistance grant ever (US$200,000) for an air surveillance program. As historian Elizabeth Hinton writes, “A new era in American law enforcement had begun.”

Today, the left-leaning Bernie Sanders has called for police to “demilitarize” from this buildup of tanks, riot gear and advanced weaponry which began after Watts. Yet, his suggestion to make police departments look like the communities they serve also mirrors Parker’s language of professionalization and modernization from 50 years ago. Calls for citizen review boards, still seen as radical by many police departments, are simply attempts at accountability and lawfulness for those charged with enforcing the law.

The relationship between police reform and other broader black freedom struggles that were so pronounced in the Emergency Committee for Unity on Economic and Social Problems and the March on Washington continue today. The March on Washington’s call for a national minimum wage in 1963 is still a central point of contention for the Democratic Party in our current presidential primary. The Voting Rights Act, which was one of the chief victories of the civil rights movement, has been significantly rolled back.

So how can Black Lives Matter take us beyond basic questions of police reform?

Black Lives Matters protesters in Louisiana. REUTERS/Shannon Stapleton

Attorney Johnnie Cochran, famous for his role as defense attorney for O.J. Simpson, worked as an assistant on the 1963 trial in Los Angeles involving the Nation of Islam. He later recalled that although such cases were difficult to win, “the issue of police abuse really galvanized the minority community. It taught me that these cases could really get attention.”

The issue at stake, then, is how to take this opening and not only begin to secure justice for the lives lost to police violence, but also to expand on questions about what it means to value black life. This can be done, I believe, by continuing to center trans and queer people of color, by remaining unapologetically black and by joining in solidarity with labor struggles.

In the aftermath of Dallas, when the media will recycle old tropes to make “Black Power” synonymous with violence, Black Lives Matter must continue to think bigger and broader. As Michelle Alexander pointed out several days ago, this is not about fixing police, this is about fixing our democracy.

(Garrett Felber is Ph.D. Candidate in American Culture, University of Michigan).

This article was first published on The Conversation.