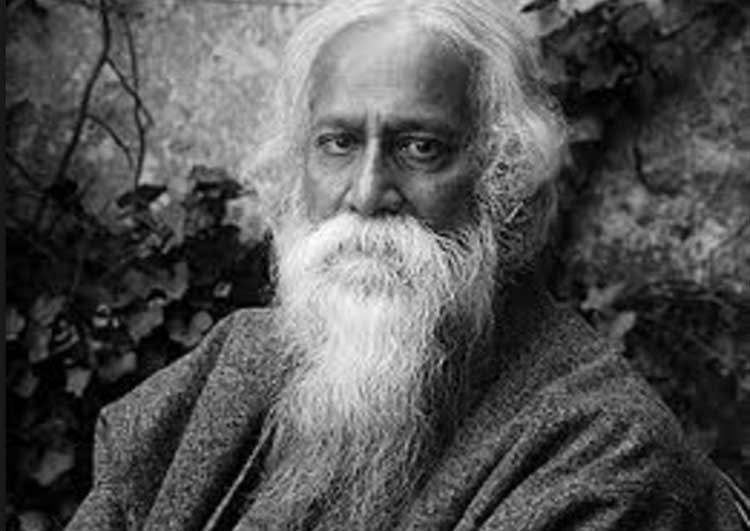

Rabindranath Tagore, the preeminent Bard of the Orient was the mercurial mystic and polymath whose repertoire was unprecedented in proliferation. Transcending to a legendary status, whilst living, Tagore created a teeming ecosystem of art, literary, musical and fine, and wholly constituted an entire era and genre in Bengali art and culture. Such was the influence of Tagore, a man who, amongst others, composed two national anthems, an overwhelmingly vast repertoire of original folk music and won Knighthood and the Nobel Prize for Literature. A BBC poll ratified Tagore as the second greatest Bengali of all time, next only to Sheikh Mujibur Rehman.

However, an oft unnoticed facet of this multiarmed polyglot, is remarkably, that of an undeniable bigot. Albeit Tagore did much to overhaul the exploitative social system and was the harbinger of progressive, modernist thought in Bengal, he was no Namboodripad or Nehru. Averse to the Abrahamic religions, and in spite of all ideological reformist endeavours, Tagore harboured an unmistakably soft spot for Hinduism, his religion of birth and upbringing.

Some of these historically sidelined figments and excerpts from Tagore’s works are presented herefore:

“There are two religions in earth, which have distinct enmity against all other religions. These two are Christianity and Islam. They are not just satisfied with observing their own religions, but are determined to destroy all other religions. That’s why the only way to make peace with them is to embrace their religions.”

Original works of Rabindranath Vol. 24 page 375, Vishwa Bharti; 1982.

Tagore spews even more vitriol towards the Muslim community; In typical demonising fashion that was the omnipresent and omniprevalent norm of the day; scapegoating of Muslims for social ills, a prevailing mood of nationwide unrest and shortcomings of the traditional institutions, in general, is depicted in his works as is the prevailing notion of Hindu generosity. Keenly and unambiguously reflected in his writings is, a lopsided, exaggerated Hindu victimhood and romanticised, pontificated tolerance. Unfortunately, this biased majoritarian, misconceived notion endures till date, with ubiquity.

One such excerpt goes as:

Whenever a Muslim called upon the Muslim society, he never faced any resistance-he called in the name of one God ‘Allah-ho-Akbar’. On the other hand, when we (Hindus) call will call, ‘come on, Hindus’, who will respond? We, the Hindus, are divided in numerous small communities, many barriers-provincialism-who will respond overcoming all these obstacles? “We suffered from many dangers, but we could never be united. When Mohammed Ghouri brought the first blow from outside, the Hindus could not be united, even in the those days of imminent danger. When the Muslims started to demolish the temples one after another, and to break the idols of Gods and Goddesses, the Hindus fought and died in small units, but they could not be united. It has been provided that we were killed in different ages due to out discord. Weakness harbors sin. So, if the Muslims beat us and we, the Hindus, tolerate this without resistance-then, we will know that it is made possible only by our weakness. For the sake of ourselves and our neighbour Muslims also, we have to discard our weakness. We can appeal to our neighbour Muslims, `Please don’t be cruel to us. No religion can be based on genocide’ – but this kind of appeal is nothing, but the weeping of the weak person. When the low pressure is created in the air, storm comes spontaneously; nobody can stop it for sake for religion. Similarly, if weakness is cherished and be allowed to exist, torture comes automatically – nobody can stop it. Possibly, the Hindus and the Muslims can make a fake friendship to each other for a while, but that cannot last forever. As long as you don’t purify the soil, which grows only thorny shrubs you can not expect any fruit.

“Swamy Shraddananda’’, written by Rabindranath in Magh, 1333 Bangabda; compiled in the book ‘Kalantar’

It’s an unmistakable allusion to the prevailing preconception of Islam being inherently violent and the adherents to the faith being somehow extraordinarily hard-line, firebrand fundamentalists. In India, the unjust label of qattar (staunch) is still recklessly used to refer to the community, implicating mindless hypercharge and invoking connotations of blind faith and unnaturally devout, religion-inspired animosity.

- When two-three different religions claim that only their own religions are true and all other religions are false, their religions are only ways to Heaven, conflicts can not be avoided. Thus, fundamentalism tries to abolish all other religions. This is called Bolshevism in religion. Only the path shown by the Hinduism can relieve the world form this meanness. Tagore, `Aatmaparichapa’ in his book `Parichaya’

- The terrible situation of the country makes my mind restless and I cannot keep silent. Meaningless ritual keep the Hindus divided in hundred sects. Sop we are suffering from series of defeats. We are tired and worn-out by the fortunes by the internal external enemies. The Muslims are united in religion and rituals. The Bengali Muslims the South Indian Muslims and even the Muslims outside India-all are united. They always stand untied in face of danger. The broken and divided Hindus will not be able to combat them. Days are coming when the Hindus will be again humiliated by the Muslims. “You are a mother of children, one day you will die, passing the future of Hindus society on the weak shoulders of your children, but think about their future.” From the letter to Hemantabala Sarkar, written on 16the October, 1933, quoted in Bengali weekly `Swastika’, 21-6-1999

- A very important factor which is making it almost impossible for Hindu-Muslim unity to become an accomplished fact is that the Muslims can not confine their patriotism to any one country. I had frankly asked (the Muslims) whether in the event of any Mohammedan power invading India, they (Muslims) would stand side by side with their Hindu neighbours to defend their common land. I was not satisfied with the reply I got from them… Even such a man as Mr. Mohammad Ali (one of the famous Ali brothers, the leaders of the Khilafat Movement-the compiler) has declared that under no circumstances is it permissible for any Mohammedan, whatever be his country, to stand against any Mohammedan.”Rabindranath Tagore, Interview of Rabindranath Tagore in `Times of India’, 18-4-1924 in the column, `Through Indian Eyes on the Post Khilafat Hindu Muslim Riots. Also in A. Ghosh: “Making of the Muslim Psyche” in Devendra Swamp (ed.), Politics of Conversion, New Delhi, 1986, p. 148. And in S.R. Goel, Muslim Separatism – Causes and Consequences (1987).

“Dr. Munje said in another part of his report that, eight hundred years ago, the Hindu king of Malabar (now Kerala) on the advice of his Brahmin ministers, made big favor to the Arab Muslim to settle in his kingdom. Even he appeased the Arab Muslims by converting the Hindus to Islam to an extent to making law for compulsory conversion of a member of each Hindu fisherman family in to Islam. Those, whose nature is to practice idiocy rather than common sense, never can enjoy freedom even if they are in the throne. They turn the hour of action in to a night of merriment. That’s why they are always struck by the ghost at the middle of the day.”

“The king of Malabar once gave away his throne to idiocy. That idiocy is still ruling Malabar from a Hindu throne. That’s why the Hindus are still being beaten and saying that God is there, turning the faces towards the sky. Throughout India we allowed idiocy to rule and surrender ourselves to it. That kingdom of idiocy – the fatal lack of commonsense – was continuously invaded by the Pathans, sometimes by the Mughols and sometimes by the British. From outside we can only see the torture done by them, but they are only the tools of torture, not really the cause. The real reason of the torture is our lack of common sense and our idiocy, which is responsible for our sufferings. So we have to fight this idiocy that divided the Hindus and imposed slavery on us……..If we only think about the torture we will not find any solution. But if we can get rid of our idiocy, the tyrants will surrender to us.”

[’Samasya,’ (The Problem), Agrahayan, 1330 Bangabda, in “Kalantar”.]

Tagore perhaps could’ve taken a leaf out of the book from another national poet from the subcontinent, composer of an ulterior national hymn Saare Jahaan se Achha, which has since been conferred a quasi-National Song status, both formally and informally and once a prime contender for the National Anthem of India, subsequently losing it to Tagore’s Jana Gana Mana. The self-christened Shayar-i-Mashriq (Poet of the East) Muhammad “Allama” Iqbal, was a glowing beacon of harmonisation and harmoniser of seemingly insurmountable, abyssal interconflicts.

Furthermore, Bangladesh’s national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam, a distinct epitome in his own, illustrated the essentiality of his creativity and his indiscriminate, pure, ingenuity, in his elegant renditions of humanhood, transcendental of narrow sectarian bounds, and his writings on Kali, and Durga Puja beautifully portray and capture the soul of the land, its culture and humanitarianism. Nazrul’s philosophy, underlying and characterising all his vibrant work, was naturally neutral, not artificially secular-conformist, or modified for the sake of integrity. His spirit was integral in origin and character.

At a time when partisanship to carve out Pakistan and muslim intelligentsia and top-brass were overwhelmingly in favour of the two-nation theory, Iqbal’s hymns Saare jahaan se achchha hindostaan hamaraa (Our Hindustan is better than all of the world) and Kuchh baat to hai hum-mein ki hasti mitati nahin hamaari... (There must be some [virtue] in us, that our [civilization’s] grandeur is indelible [and unbroken]) were wielded to foster a sense of togetherness and all-pervasive patriotism in unison. However the most well-intended rime of the poet, comes in the form a couplet, that conspicuously reflects his masterful reconciliation and intricate elegant diplomacy, which appeased all and irked none:

At a first glance, Raama, a manifestational formful Hindu deity seems irreconcilable with an Abrahamic religion that contends a single omnipotent, attribute-free Almighty. Islam doesn’t permit devoted exaltation or venerating chanting of anyone but Allah, the Supreme, but Iqbal bypasses the need to deify Lord Raama, yet beautifully augment him to unmistakably typical, traditional Islamic adulation. Iqbal accomplishes this with a succinct, idyllic and refreshingly original verse:

Hai raam ke vajūd pe hindostāñ ko naaz;

ahl-e-nazar samajhte haiñ is ko imām-e-hind.

(India is mighty proud of Raama’s sacred name,

Discerning minds respect his word as voice of God [Priest/Cleric/Clergyman].)

[Translated version of poem ‘Ram’. Taken from ‘Allama Iqbal, Selected Poetry’ By Muhammad Iqbal, K. C. Kanda]

Thus, Iqbal forges two identities into a seamless, eclectic, eclessiastical continuum, simultaneously capturing national imagination and popular Hindu sensibilities, while ruffling none of the Islamic sensibilities, if not embellishing. Iqbal’s spirited verse was no artifical flattery and appeasement, merely an expression of his cultural pride in the subcontinental spiritual aesthetic and heritage.

In an era when colonial intervention and systematically undertaken divide-and-rule policy stoked up communal sentiment, Iqbal’s hymns were used to exert a pacifying effect, foster mutual understanding and fraternal faith, and alleviate two-way distrust and alienation. Meanwhile, numerous contemporary works serve to bellow air into the rife blaze and undo the long-constructed brotherhood. Art, like nuclear energy is ambivalent: in hands of demagogues, it’s a weapon of mass destruction. Creativity is potentially, the most destructive of forces: it’s up to us, where we aim it, at prejudices, or understanding.

Tagore was too elegant a freethinker to be indoctrinated, nonetheless, his beliefs were skewed against the inherent equality of faiths and lopsided to glorify the inherent pacifism, fraternity and moral chastity of his own. They stand in testimony to men being a product of their times and also, choices, as the former argument would make the work of contemporary activists, stand for naught. They remind us to remain ever-skeptical-in-retrospect, question our spoonfed and hardwired cultural notions, demystify and rescind and the crux of no figure being sacrosanct enough to be unquestionable. Let this serve as an iconoclast to rescind their romanticism, rid of the deification and edification, and strip our historocultural idols of their invariably accompanying entitlements, in general. They command our utmost respect and unquestioned ideological allegiance, and serve as role models, inspirations and idols to innumerable; It’s time they prove themselves worthy of it.

Albeit, spoken in a different context, this unanimously relatable excerpt, by Tagore’s own admission, is pertinent to conclude the aforesaid: “My debts are large, my failures great, my shame secret and heavy; yet I come to ask for my good, I quake in fear lest my prayer be granted.”

Pitamber Kaushik is a journalist, columnist, amateur researcher, activist, and writer, having previously written for The Telegraph, The Gulf News, The Sunday Independent, and The New Delhi Times, amongst numerous other national and international newspapers and outlets.

Courtesy: Counter Current