The Gathbandhan, a grand alliance of secular forces committed to uplifting the subalterns, or a substantial part of them at least, has shockingly fared rather poorly in Uttar Pradesh. Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), Samajwadi Party (SP) and the Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD) together ended up winning only 15 out of UP’s 80 parliamentary constituencies.

The BSP won Ambedkar Nagar, Amroha, Bijnor, Ghazipur, Ghosi, Jaunpur, Lalganj, Nagina, Saharanpur and Shrawasti. The SP won Azamgarh, Mainpuri, Moradabad, Rampur and Sambhal. While BJP ally Apna Dal picked up Mirzapur and Robertsganj, the rest were all won by the BJP.

Ever since the election results were declared, political pundits, professors and senior journalists have been feverishly trying to explain how the caste quotient worked in UP.

The caste conundrum: What do experts say?

According to Athar Husain, Director, Centre for Objective Research and Development (CORD), “More than 70% Muslims, Jatavs and Yadavs and 35% Jats voted for the Gathbandhan. On the other hand, more than 70% upper castes and non-Yadav OBCs, and around 55% non-Jatav Dalits and 55% Jats backed the BJP.” Explaining the significance of these numbers, he explains, “Muslims, Yadavs and Dalits constitute around 49% in UP. Remove non-Jatav Dalits, which is around 10% of the population, and that reduces the Gathbandhan ‘s core constituency to 39%. This percentage is not spread evenly across the state. The BJP ability to draw non-Jatav Dalits on its side was crucial. So, here I want to emphasise that Gathbandhan was hugely successful in garnering its core vote and reached the figure of 40% which is huge by any count, but overwhelming consolidation of Upper Caste Hindu vote with huge chunk of MBC’s (non-Yadav OBCs) and non Jatav Dalits went to BJP which gave it roughly a lead of 9-10%.”

Which means that the Gathbandhan’s simplistic assumption that, to consolidate their main caste base –and also tactically give representation to those among the Kurmis, Nishadhs and Patels – would work, was simply not enough. That the ‘grand old party’, the Congress chose this particular election ‘to effect a comeback’ in UP and go it alone, also did not help. Our calculations show that in at least 13 seats it was the INC that stole victory from the Gathbandhan. Which assumes then, that even if it had been within the alliance, of the 80 parliamentary seats in UP, only approximately 28 were assured. Simple vote and caste arithmetic appear to have been beaten by the gross use of a money and resource funded publicity campaign and attendant dissemination/organisation.

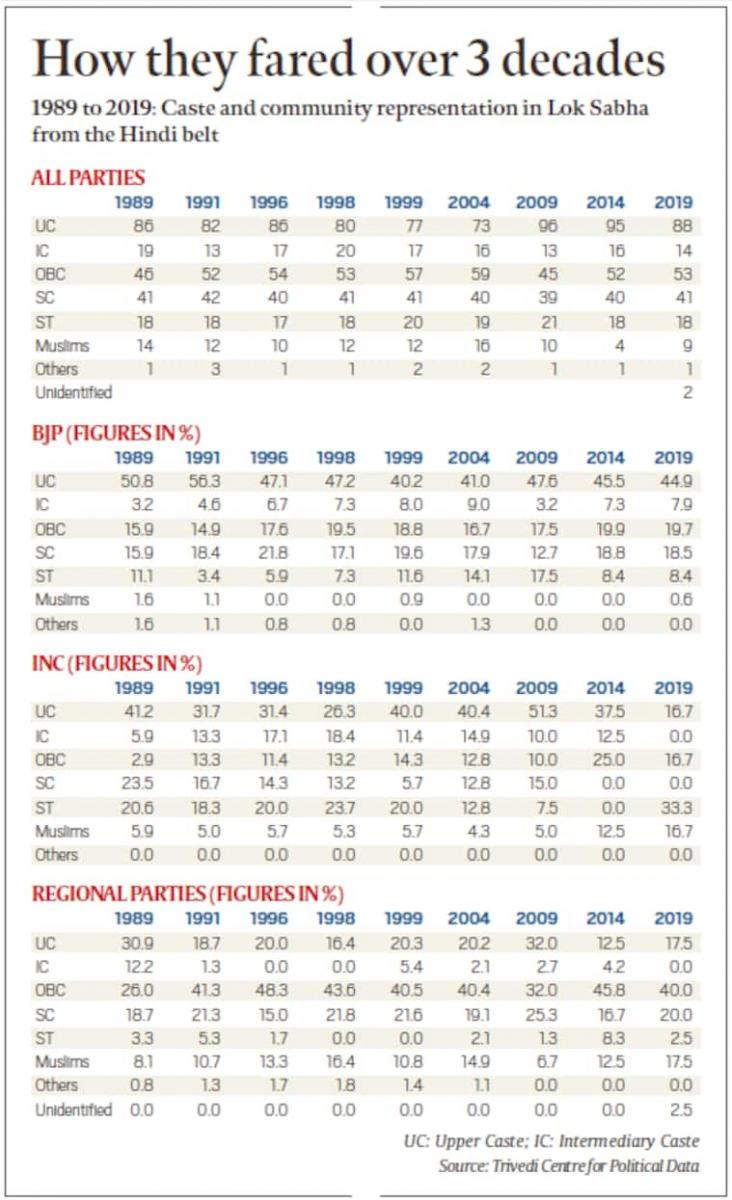

Meanwhile, Christophe Jaffrelot and Gilles Verniers have made another important observation about upper castes dominating the new Lok Sabha in this piece in the Indian Express. Citing data from the Trivedi Center for Political Data (Ashoka University) and the CERI (Sciences Po), the duo have chosen to focus on the Hindi belt calling it the “crucible of the Mandalisation of Indian politics in the 1990s”.

Jaffrelot is Senior Research Fellow at CERI-Sciences Po/CNRS, Paris, Professor of Indian Politics & Sociology at King’s India Institute, London, and non-resident scholar at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Gilles Verniers is Assistant Professor of political science, and Co-Director, Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University.

They go on to write, “This decade saw the percentage of OBC MPs doubling – from 11% to 22% – at the expense of the upper castes, largely because of the Samajwadi Party and the Bahujan Samaj Party, but also because of the nomination of lower caste candidates by the Congress and the BJP, a party that used to be known as a “Banya/Brahmin” party, but which realised in the 1990s that OBCs could not be ignored anymore – as evident from the appointment of Kalyan Singh as Chief Minister in 1991.

“However, the last decade has seen the return of the savarn (upper caste) – and the erosion of OBC representation – along with the rise of the BJP. This trend started in 2009, but the Modi wave of 2014 has confirmed it and the last elections have resulted in a certain consolidation of this come back to the pre-Mandal scenario.

Data from SPINPER project – The Social Profile of the Indian National and Provincial Elected Representatives.

Highlighting BJP’s return to its savarna heavy cadre, they say, “BJP has nominated 88 upper caste candidates out of 147 non-reserved seats in the Hindi belt and 80 of them have been elected.”

Jaffrelot and Gilles also highlight how the BJP has chosen to stick with Brahmins and Rajputs. They write, “… out of 199 BJP candidates in the Hindi belt, 37 were Brahmins and 30 were Rajputs – 33 and 27 have been respectively elected.”

It appears that the BJP has also tried to counter the Yadav votes (that typically go to the SP) by pitching eight Kurmi candidates (7 got elected) and many others from smaller OBC ‘jaatis’. Similarly, to counter the Jatav votes (that typically go to the BSP) the BJP fielded candidates from non-Jatav communities. The BSP has increasingly been come to be known as solelyu representative of the Jatav section among Dalits. The BJP also fielded 14 Jat candidates.

This chart shows the caste distribution of BJP and INC candidates.

Data from SPINPER project.

What do the subalterns want?

Both these analyses are on point when it comes to statistics, but understanding the motivations and sentiments requires a more complex and layered approach. Are the needs of the Yadavs different from those of the non-Yadavs? Has the SP by being seen as solely a “Yadav” party self-limited itself ? Have the Jatavs and non-Jatavs Dalits experienced different forms of oppression and exclusion? Or is it that by being exclusive of other Dalit sections the BSP has itself not followed the ‘Bahujan’ concept as politically conceptualised by Kanshiram? How homogenous are these caste identities? Is there scope for heterogeneity even within the same caste? Do they all vote alike? What do they want from their elected representatives?

Is it still just an existential struggle about roti-kapda-makaan and bijli-paani-sadak? The BJP famously drove home the ‘success’ of their many populist schemes including Ujjwala Gas, Swachha Bharat and PM Awas Yojana through an ingenuous misuse of advertisement and marketing resources. In this piece in Firstpost Parth MN shows how the BJP showed it all as work in progress and used that to encourage people to vote them back into power.

He writes, “I travelled through the Hindi heartland for three months ahead of the results on 23 May. It was impossible to not hear the paeans of Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana and the Swachch Bharat Abhiyan, especially in rural areas, where the Opposition expected to make inroads using agrarian crisis and unemployment.”

He goes on to say, “I met families who benefited from these schemes. I met people who are waiting for the schemes to reach them. More importantly, those who have not yet availed of the schemes know it has reached their neighbourhoods.” Comparing the BJP’s strategy to Hirschman’s Tunnel Effect, he says, “… if people belonging to your class, caste or religion are seen to be part of a sort of a transformation, you tend to be more patient towards the process. Hirschman’s Tunnel Effect has played a significant role in Narendra Modi’s success during the 2019 Lok Sabha election.”

Parth MN also echoes the longstanding belief that the BJP targets specific castes. He writes, “The politics of welfare has also helped Modi consolidate his caste arithmetic. In Uttar Pradesh, for example, the BJP’s focus has been on the non-Yadav OBCs, and non-Jatav Dalits. They are the ones largely considered to be the swing factor, with Yadavs and Jatavs firmly behind the Samajwadi Party and Bahujan Samaj Party respectively.”

Also one cannot ignore the aspirations of young Dalits, Adivasis and Bahujans, and their idea of India. Did the feverishly jingoistic pitch of the BJP’s post-Pulwama ‘nationalist’ campaign capture the imagination of the savarna and subaltern voter alike?

Let us also not forget this piece in The Caravan that highlights the caste of Pulwama martyrs saying, “…the Hindutva nationalism of the urban middle-class, largely spearheaded by right-wing groups, conveniently exploits the sacrifices of the downtrodden.” Given how many men from socio-economically deprived backgrounds, including several from historically oppressed castes end up enrolling in various defence and para-military forces, the ‘nationalist’ sentiment among the youth in these communities cannot be ignored.

What women want?

Add to this the calibrated approach of the women’s wing of the RSS in reaching out to women voters in UP, recognising their need to be recognised as a part of the political process. The communication was customised to appeal to urban women, rural women and even Muslim women. Speaking to us exclusively on the condition of anonymity, a woman who is a part of the Rashtriya Sevika Samiti and went door to door speaking to women voters, told us, “Before the campaigns, the members of the women’s wing were given some tips on talking to the women voters. We were even provided with specialised and specific data that cannot be collected by the common man.” Although the women’s wing didn’t explicitly request the women voters to vote for BJP, their meetings were designed to hint towards the Modi government and its policies. They discussed the various schemes launched during Modi’s regime such as ‘Beti Bachao Beti Padhao’, ‘Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana’, ‘Swachh Bharat Abhiyan’ among others. Read our exclusive story here.

Women, especially those from historically oppressed castes and socio-economically backward communities, face multiple layers of oppression on account of their gender, caste and economic background. With a gradual but steady increase in awareness and education, and also after surviving domestic violence and sexual harassment for generations, it is ludicrous to presume that these women will vote only as directed by the men in their families and communities.

Remember how the women’s vote had swung the election in favour of Nitish Kumar who promised prohibition if he came to power during the Bihar assembly elections in 2015. It remains to be seen how the Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi woman voted.