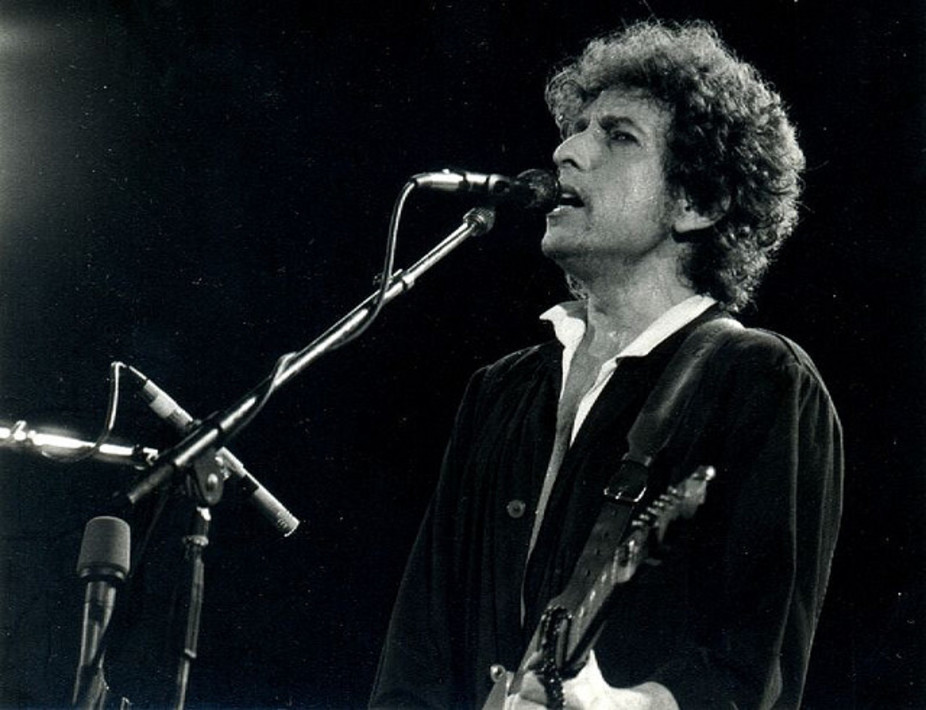

Bob Dylan in 1991. Xavier Badosa, CC BY-SA

One side of the debate was occupied by those who deny that a songwriter should be identified as a poet. The Swedish Academy, supported by popular opinion, presented the counter-argument, and Dylan is now listed first among the “Most Popular Literature Laureates”, ahead of such luminaries as Pablo Neruda, Albert Camus or Toni Morrison.

This is a surprising spot in literary history for someone who once described himself as a song and dance man, but Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy Sara Danius insists that Dylan “can be read and should be read, and is a great poet in the grand English poetic tradition”. Dylan himself seems to demur: toward the end of his Nobel address he says, “songs are unlike literature. They’re meant to be sung, not read”.

The sung-not-read distinction has long been a key issue in this debate. Composer Pierre Boulez argues that specialisation has divided speech from music, so that now each must obey discrete and specific laws of semantics and structure. They are no longer necessarily in harmony, though they still find points of connection, in song. As poet and critic David Orr notes, “A well-written song isn’t just a poem with a bunch of notes attached; it’s a unity of verbal and musical elements”.

Orr doesn’t offer the Academy’s argument that a songwriter can be a poet, insisting instead that there is a distinction between a poem and a song. He has a lot of support for this, because though there are songs that are remarkably poem-like; and poems that work better in spoken than in written form, there are distinct differences, in terms of genre and of function, between the two forms.

Poems, generally speaking, behave on the page, and operate against silence. Song lyrics, generally speaking, perform in sound, and operate in a relationship with musical apparatus.

The use of language differs too, in the two forms. Both song lyrics and poems exploit and rely on linguistic devices such as imagery, expressiveness, rhythm, cadence, concision, and word association. Poets have at their disposal little more than grammar, syntax and lexical choices.

Musicians have all that, plus a stack of sonic resources. These include melody, harmony and instrumentation; the stressing or slurring, and stretching or truncating of words, as needed to fit the musical shape; as well as meaningless but useful utterances. While rarely found in any but the most experimental of poems, oo-oo-oos and la-la-las can perfectly punctuate a song, enrich its song texture, and capture its listeners.

Songs also make more use of repetition than do poems: in part because the music may demand that a phrase or line be repeated; in part because the conventions of song include the use of a refrain, which is rare in contemporary poetry, largely because it doesn’t suit the poems though it is often vital in a song. Tom Wait’s Time — a very poetic song — includes a chorus that is all repetition:

And it’s time time time / and it’s time time time / and it’s time time time / that you love / and it’s time time time.

I love this, when Waits sings it, and it provides an important transition between the wild imagery of the verses. But when I read these lines, in the absence of the music and the voice, I feel as though I am in the presence of a mistake.

Does any of this matter — need the boundaries between song and poem be patrolled and policed? Possibly not. After all, as 18th-century Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico suggests, we humans came to language through song; and song and poetry together built the linguistic domain we now inhabit.

But there’s more to it than theory; there’s also taxonomy, and the distribution of resources that follows cultural classifications. Musicians can become rich and famous from their work; poets rarely do. Musicians can compete for the distinction associated with what is still called “high” culture, but poets rarely get to enjoy the rewards of “popular” culture.

Bob Dylan, for example, has won a shelf full of Grammies for the same body of work that delivered his Nobel Prize in Literature. Oxford Professor of Poetry Simon Armitage has won the Ivor Novello Award, but that was specifically for his song lyrics: his poetry was not eligible.

As long as the river flows in only one direction, it seems likely that poets will continue to resist attempts by songwriters to occupy their patch.

Jen Webb, Director of the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.