Hearings in the Supreme Court to decide if Indians have a fundamental right to privacy ended on August 2.

Hearings in the Supreme Court to decide if Indians have a fundamental right to privacy ended on August 2.

The judgement is expected by August 28, as that’s when the term of Chief Justice of India JS Khehar — who’s heading the 9-judge Constitutional Bench deliberating the question — ends.

The apex court’s decision — whether privacy is indeed a Constitutionally protected fundamental right or a common law right (which, according to experts,can be taken away by any enacted law) — will have far-reaching consequences for the civil liberties of Indian citizens.

It will also bring to climax a roughly 9-year-old fight, inside and outside court, between a heterogeneous group of activists and the state — irrespective of the ruling governments in that time — over the project of Aadhaar, the 12-digit biometrics-linked Unique Identification (UID) number to be issued to all residents.

If the 9-judge bench rules that privacy is a fundamental right, a five-judge bench will decide whether Aadhaar violates such a right. There are at least 20 petitions in the Supreme Court challenging Aadhaar on various grounds, including it being made mandatory for provision of essential state services for citizens—despite SC orders that it cannot be made mandatory except for six schemes.

The brainchild of tech billionaire Nandan Nilekani, the UID project has been dubbed variously as “the world’s largest mass surveillance project ”, “the biggest social project on the planet ”, and the like.

It has also been pushed along, mostly illegally, by the state since 2009 — the UPA and the current NDA, of course, setting precedents for much in the country.

Why did first-world countries that took up similar projects abandon them?

The United Kingdom, for example, had a biometrics-linked National Identity Card project to create a centralised register of sensitive information about residents similar to Aadhaar, which was scrapped in 2010.

The reasons were the massive threat posed to the privacy of people, the possibility of a surveillance state, the dangers of maintaining such a huge centralised repository of sensitive information, and the purposes it could be used for, and the dangers of such a centralised database being hacked. The other reasons were the unreliability of suh a large-scale biometric verification processes, and the ethics of using biometric identification.

In India, the government has resorted to all kinds of arguments and claims to make the case against the Constitutional guarantee of privacy, and to knock down the last obstacle against Aadhaar.

The government has called privacy an “elite” concept, pitched the Right to Privacy against Right to Food that they claim can be fully realised only through Aadhaar, and even made the claim that it is “impossible” to track citizens using Aadhaar.

Whose interests will the UID database serve? The poorest of the poor, claims the government. Not so, says the opponents. It is a surveillance measure in the guise of welfare.

Hurting welfare

The premise on which the Congress-led UPA (then opposed by the BJP) and now the BJP-heavy NDA have pushed the UID project is welfare — as the instrument to ensure smooth, efficient, ‘targeted’ implementation of the Public Distribution System (PDS) as well as all other social welfare schemes in the country.

The state has maintained that Aadhaar will eliminate corruption and “leakages” in delivery of benefits, weed out “ghost” beneficiaries by way of de-duplication of identity, resulting in huge savings for the government exchequer, and of course, end poverty.

Now, the importance of ‘identification’ cannot be overstated for ensuring that benefits reach those they are meant for, especially in a country like India. A substantial part of the population has an unrecognised, informal existence and subsistence—many without a single official documentation of their identity, which bars them from accessing government benefits. The UPA used this argument as basis for Aadhaar, but was opposed by the BJP, worried primarily over illegal immigrants being given a UID number as well.

But with the NDA now, the focus seems to have shifted to fighting “ghost” beneficiaries and saving big money .

In the Supreme Court, the Attorney General KK Venugopal, returned to the inclusion argument, and said that Aadhaar was essential for the Right to Food, claiming that “Aadhaar has ensured that food reached 270 million persons who live below the poverty line through social welfare schemes.” He then went on to argue that the Right to Privacy for a small elite group of people could not override the Right to Food, which is part of the Right to Life.

This drew a vehement response from the Right to Food Campaign , which issued a statement highlighting the massive exclusions that have taken place by linking Aadhaar to everything from PDS, pensions, mid-day meals, MGNREGA wages, and nearly all other social welfare schemes and benefits.

The campaign said, “According to data put out by state food departments, in Rajasthan 33 lakh families are unable to access their Public Distribution System (PDS) ration entitlement each month due to the linkage of the PDS with Aadhaar. Similarly in Jharkhand, 2.5 lakh families are deprived of their grain entitlements on a monthly basis.

In June 2017, in Ranchi District, only 67% were able to buy their grain through Aadhaar-Based Biometric Authentication.”

Speaking to Newsclick, Dipa Sinha of the Right to Food Campaign said, “Aadhaar has created problems for beneficiaries at all stages, from failure in biometric enrolment to the monthly verifications. The most common reasons are finger prints not matching, poor internet connectivity that is required for Point of Sale machines to work and verify, etc.”

“The UIDAI admits an error rate of around 5%. Even that is a very large number in terms of everyday transactions. But we have found an error rate of 25-30%. Now imagine how large a number that is of people being denied their basic entitlements like food, pension, wages, etc. And these are the most vulnerable sections of society, the poor, the old, the daily wage workers, the impoverished disabled, among others,” she said.

Over the past few years, there have been numerous studies and reports of the devastation that Aadhaar linkage has caused to the welfare schemes, including by civil society group Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan and economist Jean Dreze .

Dreze has also refuted the claims of Aadhaar exposing “ghost” beneficiaries getting mid-day meals, for instance.

Economist Reetika Khera told Newsclick, “The government tried to tell the Supreme Court that the right thing life is above the right to privacy and that Aadhaar was essential for the realisation of the right to life. This is so far from the truth. The application of Aadhaar in the PDS, NREGA, pensions, etc has in fact endangered the right to life of lakhs of people by denying them their right to food and work.”

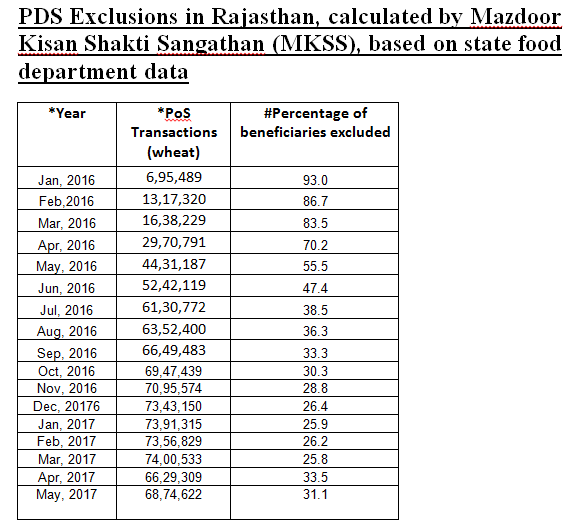

*Source: http://food.raj.nic.in/DistrictWisePOSDetails.aspx

# Percentage calculated based on number of beneficiaries as on 04/06/2017: 99,77,909

The Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) analysed the Rajasthan state food department data for monthly Point of Sale (PoS) machine transactions for wheat in all 33 districts.

In Rajasthan, Aadhaar was made mandatory for getting supplies from PDS from September 2016. The pilot linking of Aadhaar to PDS was started in January 2016.

Courtesy: Newsclick.in