At a time when the country is celebrating Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav to mark the 75th year of Independence and the deepening of democracy, our educational institutes remain highly undemocratic. Decades after the freedom from colonial rule, the marginalized community including SCs, STs and OBCs remain under-represented.

While the OBC reservation is 27%, the proportion of OBC professors at 45 central universities is just 4%! At the associate professors and assistant professors levels, the bleak scenario does not change much as their share increases slightly to 6% and 14%, respectively.

The information is based on the data presented in the Lok Sabha by Union Minister for Education (State) Subhas Sarkar. He recently replied to a question raised by Sanjeev Kumar Singari, a Member of Parliament (Yuvajana Sramika Rythu Congress Party) from Kurnool constituency in Andhra Pradesh.

The OBC reservation for non-teaching staff has also not been fulfilled. According to the figures, only 12% of seats have gone to them at the central universities. At present, there are only five OBC vice-chancellors at 45 central universities.

After decades of struggle, the socially and educationally backward classes were able to get 27% reservations in the early 1990s. Three decades after the historic achievement and the assertion of the OBC politics, the situation at public universities has not changed much. They continue to be monopolized by a few privileged castes.

Look at the irony. Prime Minister Narendra Modi never misses a chance to highlight his OBC identity but even his nine-year rule has not ensured justice to the members of his own castes.

Apart from OBCs, Adivasis are highly under-represented. Among professors, the share of Adivasis is only 1.6%, while they are given 7.5% reservation. Similarly, at associate and assistant professors levels, they are able to get a mere 2% and 4%representation, respectively. With 7% (professors level), 8% (assistant professors level), and 11% (associate professors level) share, Dalits are better than Adivasis but these figures are far less than the 15% reservation given to them.

While the marginalised communities remain grossly under-represented, the privileged castes are ruling the roost at the educational centres. They serve their caste privileges by monopolizing almost all seats under the general or unreserved (UR) category. As per the law, the UR category is open to all but in practice, it has been kept out of the reach of marginalized castes. Since there is no legal binding on the selection committee to take candidates from the marginalized community, the privileged castes lobby employs several methods to exclude SC, ST and OBC candidates from the UR category.

Even if their applications are accepted, during the interview, SC, ST and OBC candidates appearing under the UR category, are discriminated against and humiliated. It has been reported that these candidates have been told by the authority “not to encroach on the UR seats”. During written exams and interviews, the candidates belonging to marginalized communities are given less marks to keep them out of the race. To harass them further, the selections under the SC, ST and OBC quotas are not easily made. NFS or Not-Fund Suitable is another weapon to reject all the candidates belonging to the marginalized community. However such practices are hardly seen under the UR category. Are meritorious and suitable candidates only born in a few privileged castes?

To reiterate the point, higher education in India is yet to be democratised. Since colonial times, the upper castes have entered the system and through their caste network, they have maintained their privileges. The preceding decades indeed saw the politicization of the lower castes at the grassroots levels and a large number of OBC leaders got close to the corridor of power, but they have not been able to ensure social justice at the educational and cultural institutes. From the university to media houses, from the cinema to religious bodies, the marginalized castes remain excluded.

This is one of the main reasons that the electoral victories of the lower caste political parties do not often succeed beyond a point in making social change. For example, even for the ideologies and programmes of their parties to be brought to the masses, the lower caste leaders are heavily dependent on the upper-caste-run corporate media. During the Mandal agitation in the 1990s, the upper caste-dominated mainstream media did not support the lower castes and it went all out to demonize the politics of social justice as “divisive” and working “against the development” of the country.

Since the coming of the Modi Government in 2014, the caste supremacist lobby has become quite strong. For example, the RSS has a direct say in the recruitment process at colleges and universities. The main criterion for the selection is often not the knowledge of the subject and the ability to teach and carry out the research but the candidate’s loyalty to Hindutva ideology. Even the prestigious universities in the national capital such as JNU, Delhi University and Jamia are in the total grip of the Hindutva forces.

The selection process has been so perverted by the Hindutva forces that it has become a drive for recruiting cadres. Those who have held their independent opinion and have refused to follow the divisive ideology of RSS are deliberately thrown out of the selection process. These have all contributed to the further marginalization of marginalized communities. The political leaders from marginalized communities are either helpless or visionless to understand the gravity of the situation.

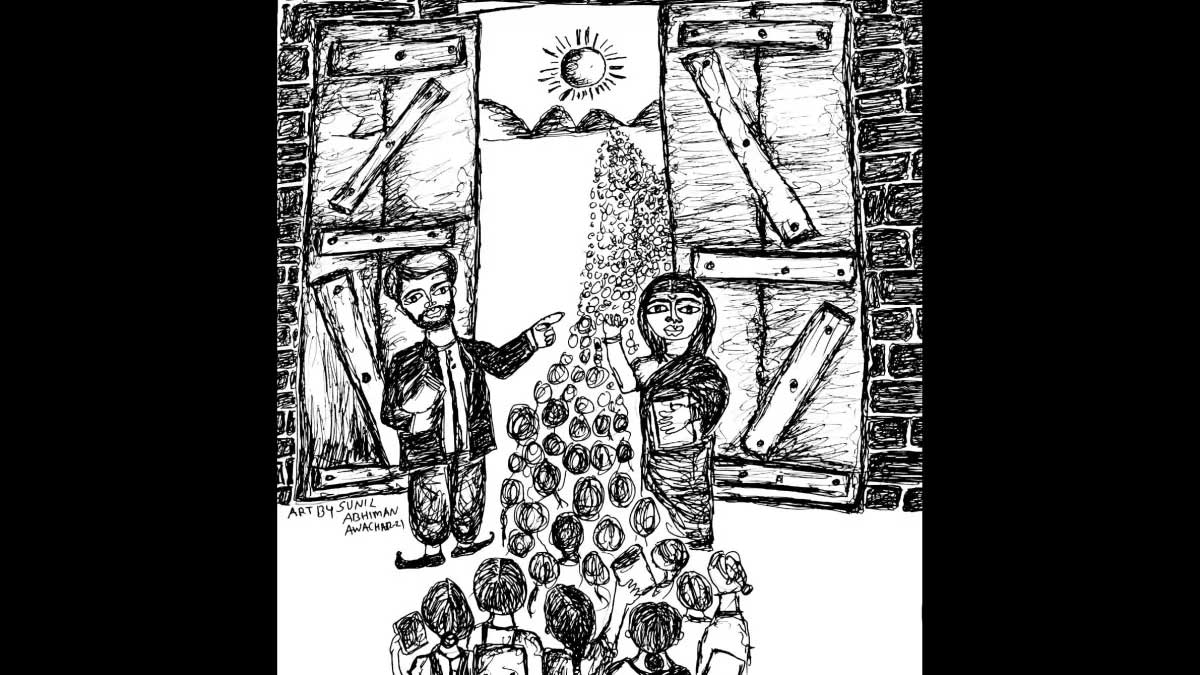

Access to education, particularly in the Phule-Ambedkar tradition, is a road to liberation. As Phule argued in Slavery (1873), the privileged castes could maintain their dominant position only because they forcefully deprived the Shudras and Ati-Shudras of education. Babasaheb Ambedkar, similarly, gave a call to educate, organize and agitate. He cautioned that if people from marginalized sections were not given representation in the key sectors of a nation, the interests of weaker sections would be jeopardized. Isn’t the exclusion of marginalized communities from the central university a re-establishment of the old order based on exclusion and inequality?

(The author is an independent journalist. He has also taught political science at NCWEB Centres of Delhi University.)