About four years ago, an excellent physicist Parameswaran Ajith had to write an article [2] explaining how Albert Einstein, the world-renowned scientist, used mathematics for his discoveries in physics. However surprising it may seem, the article was actually called for. Being a mathematician, I would like to thank him for writing it and stressing how the theory of relativity is still regarded as the pinnacle of mathematical elegance initiated by the sheer brilliance of one of the best scientists of the world. That physics uses mathematics is almost tautological – even my eleven-year-old can give a short lecture on this topic. Why did, then, P. Ajith write this article on something so obvious? The answer is long and the reason deep-rooted.

On the face of it, P. Ajith’s article would be thought of as a knee-jerk reaction to the remark[1] of a politician, who said people should not be too concerned with GDP maths, since “maths never helped Einstein discover gravity”, a comment that’s scientifically wrong on multiple counts. Neither did Einstein discover gravity (gravity was actually discovered by Issac Newton, not Albert Einstein), nor did he, in any way, refrain from using mathematics, a subject described by the legendary German polymath Carl Friedrich Gauss as the “queen of sciences”. However, in my opinion, articles like these cannot just be regarded as an immediate response to a politician’s loose, unsubstantiated and unscientific comment. They serve their purpose in overall popularization of science and clearing doubts about it among common people, whom we need to reach out as academicians, and explain our daily lives as well as the challenges therein.

Just to stress a bit more on why connecting with masses matters, I would like to share an anecdote. A reasonably rational neighbour of mine had mentioned the name of a premier science institute of India and asked me why nobody from there won a Nobel Prize despite the Government spending so much money on it. Saddened by his question, I requested him to name a few world-renowned institutions which received many Nobel Prizes in science, and he obliged. Then I bombarded him with questions such as, “have you checked the average budget per academic of those institutions in comparison to the one in India?”; “do you know how long it takes for an experimental scientist in India to order an instrument or a reagent in contrast with the time taken by one living abroad?”; “do you know how many exceptional young scientists do not want to come back to India for various reasons, including but not limited to bureaucracy, dearth of funding, lack of academic freedom, etc.?”. He could answer none and went away quickly.

Don’t we need to engage with our friends, relatives, neighbours and tell them about our problems? Don’t we need to discuss how our profession is getting affected due to whimsical decisions taken by an authoritarian regime that neither understands science nor appreciates the scientists? Don’t we need to protest against the forced propagation of pseudoscience? Don’t we, as a community, need to pitch in the fulfilment of Article 51 A(h) of The Constitution of India, which states “[it shall be the duty of every citizen of India] to develop scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”. The spirit of inquiry requires “the right to freedom of speech and expression” enjoyed by each and every citizen of our country according to Article 19(1)(a) of the same document. Scientists, or more generally academicians, cannot be an exception to this rule as pointed out in a recent article by another outstanding physicist Suvrat Raju.

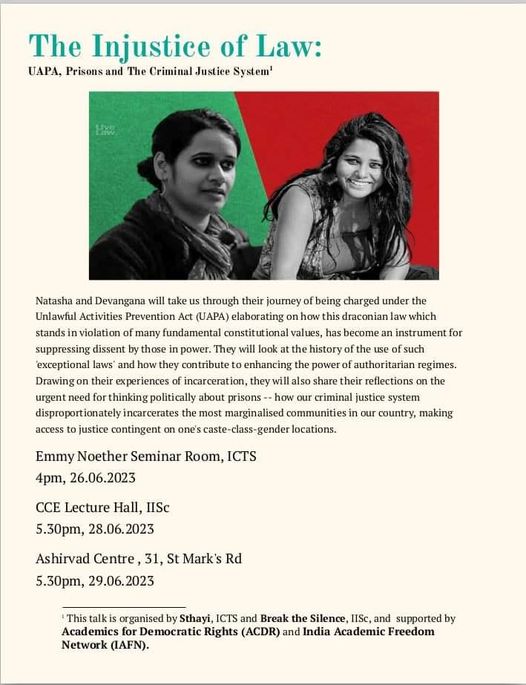

Raju’s article [3] was written at the backdrop of a series of unfortunate incidents that, much to our dismay, will have long-term adverse effect on the future on Indian academia. It involves autocratic behaviour of the administrators of two top-notch academic institutions of India. One disallowed a planned event (a talk by human rights activists Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal) at the eleventh hour curbing freedom of speech on the campus while the other sent show cause notices to two of their brightest and youngest assistant professors for signing an extremely polite letter [4] written by more than five hundred honest members of Indian academic community. Quelling of dissent has scaled new heights and taken many forms – the academia is not free from it either. Without even investigating the legality of any of these actions, just think how easily they will intimidate young academics from following their conscience in the near future. These actions will also discourage generations of prolific academicians from applying for a job in an Indian institution. Aren’t these damages serious enough for us to speak out? S. Raju’s article is a bold answer to this important question.

Whenever I talk to my colleagues about these issues, most of them give me a what-can-we-do look and silently walk away. Some, of course, are doing the needful, and I love and respect them from the bottom of my heart. A few (“a few, too few for drums and yells”?!) actually ask, “How do you think we can contribute?” It is my pleasure to respond to them directly as well as in this article. First and foremost, we all can contribute in our own ways, and within our limits and limitations. Once we understand that, half of the job is done. It is also important to realize that, just like P. Ajith and S. Raju, we need to talk about the obvious facts as well as intricate issues. If you are a mathematician like yours truly, just explain how your day is spent – trying to prove a lemma and struggling throughout the day only to discover in the evening that a special case has already been proved, and all we need to do is to extend it in the new setup. This too will be a significant contribution. You know why? It will help because your relative or your neighbour will know you aren’t wasting time using taxpayers’ money – a narrative that we need to refute at any cost.

If you are a biologist or a historian or a physicist but unable to write an article like P. Ajith or S. Raju, the least you can do is to participate in a discourse with your friends over coffee and discuss how your academic contributions matter. We, the academicians, should try our best to take a stand against each and every atrocious event around us. We tend to underestimate the usefulness of such activities but they inspire younger academics, especially students, postdoctoral fellows and even young assistant professors, and assures them they aren’t alone in the fight. We can also inform our friends, relatives and neighbours that the current oppressive regime has done away with most of the prestigious academic awards, fellowships and grants, and how we are suffering because of that. Overall, we need to be more vocal and less shy, and talk about our profession with all and sundry. That’s the only way we can ensure a better environment for our future colleagues in the years to come.

Parthanil Roy is a professor at the Indian Statistical Institute Bangalore Centre. This article is based on the author’s personal experience and opinion.

References:

[3] https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/scientists-need-the-oxygen-of-free-speech/article67076627.ece

[4] https://docs.google.com/document/d/1Oee1bwCWrbOGivqYZzvTpjg8JN6VXQP-3iDwVn9Ud_A/edit