Sitapur, Uttar Pradesh: Afsana Bano is 18, and her 5’7 frail figure and delicate bones cradled a three-day-old baby that weighed 2.6 kg instead of the ideal 3.3 kg at this stage.

Afsana Bano studied to class 12, among only 16% of women with more than 10 years of education in Uttar Pradesh’s Sitapur district. Yet, she is an underweight mother with an underweight child, ignorant of the health needs of both. Bano and her 2.6-kg child represent the failure of government adolescent, sexual health services in the state.

Bano’s situation is representative of a cycle that keeps millions of Indian mothers and children, particularly in the most populous, poorest states, undernourished and incapable of learning and earning enough, thus holding back Indian economic progress, according to several research studies.

Bano was 18 when she married and was underweight when she conceived, weighing 51 kg in the eighth month of pregnancy, gaining no more than 200 gm by the ninth. She did not think much of it because she was unaware of the consequences of an underweight child.

Studying till class 12, Bano had an above-average education in rural Sitapur, where no more than 16.4% of women have had 10 years of education, compared to 32.9% in UP and 35.7% nationwide. But she never got the attention or counselling that the government health system was supposed to give her.

This is particularly important in Sitapur, where 36% of married women are adolescents, according to the 2015-16 National Family Health Survey (NFHS)–or NFHS-4–data, compared to an average of 21% in Uttar Pradesh (UP), India’s most populous and third-poorest state, by per capita income, and 27% nationwide.

With 4.4 million people, Sitapur is classified as one of 25 “high priority districts” across Uttar Pradesh and 184 across India identified for special attention to pare child marriage and adolescent pregnancies.

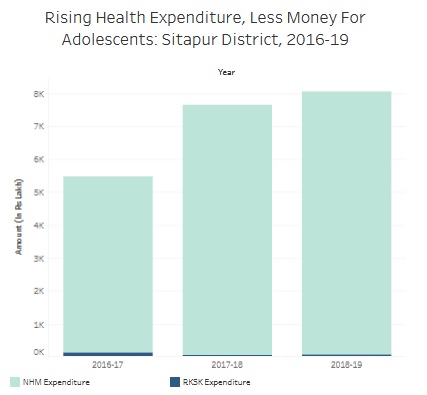

But the programme to address early marriage and teenage pregnancy, the Rashtriya Kishor Swasthya Karyakram (RKSK), a five-year-old national youth health programme, was given 1% of National Health Mission (NHM) funding in Sitapur, falling over a year from 3% in 2016-17.

Of this money a third was never spent, according to a 2019 analysis of NHM finances by Accountability Initiative, a think tank based in New Delhi, although there has been some improvement, as we explain later.

Source: Accountability Initiative, 2019 ((Data shared with IndiaSpend)

The failure of the RKSK to meet its ambitions of widening attention to adolescent sexual health and incorporating those needs into wider health programmes and effect change was acknowledged by a government spokesperson.

“The inherent problem with the programme is that the RKSK is seen as a low-priority component in NHM,” Sujit Verma, NHM’s district programme manager in Sitapur, told IndiaSpend. “The kind of demand institutional deliveries, leprosy, tuberculosis programmes have is not felt by RKSK.” The community does not consider adolescent health issues as important enough to be discussed in a hospital, he added.

“Handholding of ASHAs (accredited social health activists) and peer educators is required to develop a demand that stems from the community,” said Verma.

Developing the ‘demand’

With Bano and Sitapur, that demand has obviously not materialised. Developing the demand, as Verma put it, has wider implications.

Preventing malnutrition of children and women in what experts call a “crucial” 1,000-day window–from the start of a woman’s pregnancy to her child’s second birthday–could boost India’s gross domestic product by between $15-46 billion (Rs 1.03 lakh crore to Rs 3.17 lakh crore), according to 2013 report by Save the Children, a global advocacy. That is six times the size of India’s 2018-19 health budget.

Bano’s situation is representative of many women in Sitapur, where child marriage and early pregnancy are endemic, said experts: 7.3% of women in Sitapur between 15-19 years already are mothers, according to NFHS-4 data. Even though teenage childbearing in UP is half (3.8%) India’s average (7.9%), in Sitapur 35.5% of women are married before they turn 18, higher than the UP average of 21% and the Indian average of 27%.

It took India 19 years to bring down child marriages by 51%, according to the Global Childhood Report by Save the Children. If those numbers to fall further, adolescent health in rural areas requires immediate attention. That may be difficult without adequate data.

“Not enough information is available on younger adolescents (10-14 years), and both younger and older adolescents’ needs to be assessed differently,” said Niranjan Saggurti, India country director, Population Council, a global research organisation. “One can then get more clarity as to which adolescents are most at risk as regards reproductive health.”

Bano’s education did not prepare her for knowledge of sexual or health issues. She studied at a madrasa, or Islamic seminary, and no health worker or health programme reached her mud-and-straw home in Parsendi village, 90 km north of the state capital Lucknow, as they were supposed to–and indeed do in India’s more prosperous states, such as Kerala.

Bano’s husband, Mohammed Karim, 21, was in no position to advise her: he studied till class five and worked for awhile in a “tablet-making company”, as he put it.

Before pregnancy, Afsana visited the anganwadi–or government creche-cum-health centre–only once. The first time she visited was in the sixth month of pregnancy, which is three months later than recommended and only got one tetanus vaccination instead of the two she should have. She was given iron and calcium tablets, but they made her sick with diarrhoea, she said.

Bano never visited the anganwadi again.

The malnourishment cycle

There is every chance Bano’s child will grow up malnourished, as children of underweight mothers tend to be, and be less educated and productive than he might be.

Malnutrition is one of the leading causes of about half of India’s childhood deaths, and if they are affected at an early age, there can be long-term consequences, affecting motor, sensory, cognitive, social and emotional development. States with more educated women had healthier children, according to a March 2017 IndiaSpend analysis of NFHS-4 data.

While India’s burden of disease due to child and maternal malnutrition has been decreasing since 1990, malnutrition was responsible for 15% of the total disease burden in India in 2016, according to India: Health of the Nation’s States, a report produced by independent medical agencies, nonprofits and the government.

Nationally, there was a 9.6-percentage-point reduction in the stunting rate of children in 2015-16 compared to a decade before that. UP’s improvement rate was 10.5 percentage points, according to our analysis of NFHS data.

Home to almost a third of the world’s stunted children under five (46.6 million), India is not on track to reach the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2025 global nutrition targets, IndiaSpend reported in January 2019.

Of Indian children under two years of age, 90.4% did not receive an adequate diet, according to NFHS-4 data. About 18% of children aged 6-23 months ate iron-rich foods, and more than half the children in this age group were anaemic. About 54% consumed vitamin A-rich foods, the lack of which can lead to childhood blindness and poor immunity.

To address this situation, government health services must go to the root of the problem: the mothers. That is not easy to address, said experts, when the mothers are adolescents.

Why adolescent health matters

Adolescent health is the most critical stage in life for health interventions, according to expert advice.

“More than 33% of the disease burden and almost 60% of premature deaths among adults can be associated with behaviours or conditions that begin or occur during adolescence,” said a 2002 WHO statement.

The health of adolescent girls and young women is linked to the birth weight of the children and to child survival. Adolescent mothers become more vulnerable to problems related to pregnancy and childbearing and are more likely to have premature and underweight babies.

High maternal and child mortality in adolescent mothers and a smaller but significant contribution of adolescents to the total fertility rate (TFR) or the number of children that a woman has. UP’s TFR is 3.1, compared to 1.8 in Kerala, 1.6 in Tamil Nadu and 1.6 in West Bengal, compared to the replacement rate of 2.1, at which point population stays the same.

These data illustrate the need to make adolescent health a part of overall maternal and child health, according to a 2014 adolescent-health strategy paper from India’s ministry of health and family welfare.

RKSK in UP: Noble aims, slow spending

Launched in 2014, the RKSK was the first programme to place adolescent health at the centrestage of government health priorities.

The RKSK subsequently widened its scope from sexual and reproductive health to include nutrition, non-communicable diseases and substance abuse and has since shifted its focus from curative to preventive and aims to reach adolescents in their own environment.

These aims have not yet been met in Sitapur, where the training of what are called “peer educators”, specially trained teens aged 15 to 19 from every village, was envisaged as in the other 24 “high-priority districts”. Each of these districts was also supposed to have an adolescent friendly health centre and a counsellor.

In reality, both the RKSK and the NHM struggle to even spend the money they get.

A little more than half (55%) of NHM funds were used in UP in 2017-18, although this is an improvement from 45% in 2016-17, and, as we said, RKSK expenditure as a proportion of NMH spending fell from 3% in 2016-17 to 1% in 2017-18.

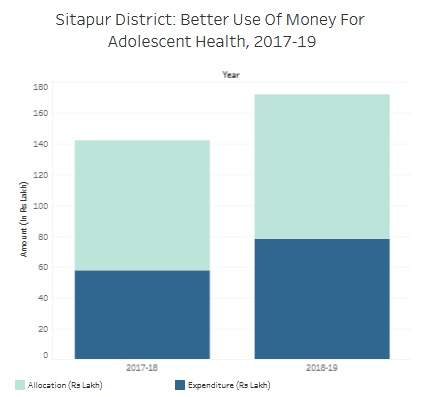

Sitapur was given Rs 1.72 crore in 2018-19 for RKSK, up from Rs 1.42 crore in 2017-18, an increase of 21%. The use of these funds increased from 41% in 2017-18 to 45% in 2018-19.

Source: Accountability Initiative, 2019 (Data shared with IndiaSpend)

“Sitapur reflects a clear low utilisation story; despite the money allocated, districts are not receiving the full amount that’s being allocated to them,” said a researcher who has worked on sexual health issues but requested anonymity because she worked with the government. “Funds are normally released only in the last two quarters, which is also why most of the funds go unused.”

On the issue of a lack of demand for adolescent health services, the researcher said that most of the expenditure in RKSK is not based on demand and was spent on training frontline workers, such as the ASHAs and peer educators.

Back in Parsendi, Bano said she lived a happy life with her husband, with whom she had fallen in love, a rare culmination to a teenage romance in a society where arranged marriages are the norm. She wanted to study further. How would she do it now that she had a child? Bano only smiled.

Correction: The story has been corrected to reflect that the estimated boost to India’s gross domestic product due to prevention of malnutrition is six times the 2018-19 health budget. We regret the error.

(Ali is a reporter with IndiaSpend.)

Courtesy: India Spend