With the help of mainstream media, the Narendra Modi-led BJP spread one of the biggest propaganda campaigns in the electoral history of India, claiming that the Opposition was nowhere in the race and that it was all set to win over 400 seats in the 2024 General Elections. But when the results were declared on June 4, the hyped campaign and the bloated arrogance of the BJP were pricked, with the BJP falling short of the majority by over 32 seats. Even though Modi was able to form a coalition government with the support of allies, including the TDP and the JDU, it was his moral defeat, as under his sole leadership, the BJP lost 63 seats compared to its figure in the 2019 General Elections.

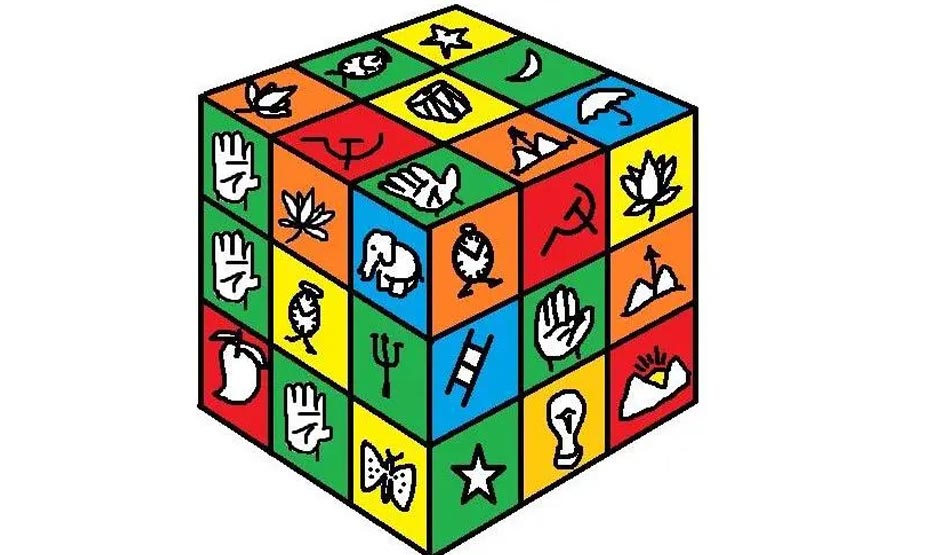

As a result, we are witnessing yet another phase of coalition government at the Centre. For the last ten years, the Central Government has been dominated by one party and one leader. However, the recent positive changes are being lamented by the mainstream media. If the views expressed by establishment-backed writers in the media are anything to go by, an impression is being created that the era of coalition politics may hamper the growth rate and be an obstacle to “strong” economic reforms.

In what follows, I would critique such a top-down approach and argue that a coalition government is good for democracy and it is conducive to strengthening the rights of the people because it creates multiple centres of power and does not easily allow one party or person to dominate the political field.

But first, we need to differentiate democracy from majority rule. The RSS and the BJP are desperate to consolidate the majority of Hindus on religious grounds and forge a “communal” majority, but such a trend is antithetical to the democratic spirit. To understand this, we need to go back to Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar.

Almost a century ago, when Dr. Ambedkar was active in politics, he anticipated the looming threat from the Hindu Right to India’s democracy. Addressing the Annual Session of the All-India Scheduled Castes Federation held in Bombay on May 6, 1945, Ambedkar spoke in unambiguous terms: “Much of the difficulty over the Communal Question is due to the insistence of the Hindus that the rule of majority is sacrosanct and that it must be maintained at all costs.”

The approach which was opposed by Dr. Ambedkar is what the BJP has done in the last ten years. Any criticism of the wrong policies of the Modi Government was rejected by the Hindu Right, saying that the BJP had the numbers while the Opposition had lost the legitimacy by losing elections.

But unlike the majoritarian logic of the RSS and the BJP, Ambedkar was quite clear that in a democracy, the government was formed by majority votes, but that did not mean that the rights of the minorities would be trampled under the strong heel of majoritarianism or the brute force of numbers. He said that “no one community is placed in a position to dominate others because of its numbers.”

Ambedkar was bang on target in defining the true spirit of democracy. For a true democrat like him, the protection of the rights of minorities, which include both religious minorities and those who are historically oppressed and socially marginalized, is a key feature of democracy. Babasaheb was aware of the danger of upper-caste-led communal majoritarianism, masquerading itself as “nationalism,” which, in turn, demonizes the legitimate demands of marginalized groups and their political mobilization as “communal” assertion. The way AIMIM president Asaduddin Owaisi is attacked by the Hindu Right every day makes Ambedkar’s words prophetic.

Two years later, Ambedkar wrote a small pamphlet, which was nevertheless a powerful document called States and Minorities, where he exposed the myth of communal majoritarianism, legitimizing itself in the form of nationalism and democracy. Look at his perceptive words, “Unfortunately for the minorities in India, Indian Nationalism has developed a new doctrine which may be called the Divine Right of the Majority to rule the minorities according to the wishes of the majority. Any claim for the sharing of power by the minority is called communalism while the monopolizing of the whole power by the majority is called Nationalism.”

If we keep in mind the insightful words of Ambedkar, we can easily see through the discomfort and anxieties of the Hindu Right and their cadre-writers with coalition politics. Contrary to the democratic spirit, the Hindu Right believes and acts on the doctrine of ‘might is right’. Similarly, they are allergic to the idea of sharing power with Bahujans such as Dalits, Adivasis, OBCs, and religious minorities. They are not ready to accept the fact that the basic difference between authoritarian rule and democracy is the question of power. For example, an authoritarian rule is non-democratic because it, unlike democracy, refuses to share power with marginalized groups.

To put it differently, an authoritarian ruler decides everything on his own. He is unwilling to listen to criticism and dissent. Under his regime, there is an absence of multiple sources of power, and the system of checks and balances has collapsed. The due procedures and the rule of law are not in place. The mechanism of dialogue and consensus has been uprooted. The freedom of the press, the independence of the judiciary, and the proportional and effective representation of minorities are anathema to the ears of the authoritarian ruler. Such tendencies could also find a leader, sweeping through the elections in majoritarian waves.

Contrary to this, a democratic system is not only the name of elections, although free and fair polls are very important. Nor is the sign of democracy merely the formation of the government and the celebration of the high growth of the economy. A true democracy, in fact, is one where the rights and interests of weaker sections and the marginalized are protected. For example, in a caste-based society like ours, the leaders from a particular section cannot be entrusted to safeguard the interests of all. Even if good policies and laws are in place, unless the people from the marginalized sections are placed in a position to implement them, these “good” laws themselves may not be effective in ensuring their rights.

Thus, participation and decentralization are the buzzwords in a democratic setup. Where the formation of the government is based on multi-party systems, authoritarian tendencies are kept in check. In electoral systems where many parties are in competition, it is likely that the political parties will offer more welfare schemes to the voters.

Unfortunately, the previous decades of Indian politics, particularly in the Centre, have been dominated by one party and one leader. This has led to the decline of consensus-building, an important feature of democracy. The previous Modi-led governments at the Centre have violated the true spirit of federalism. The last two tenures of the Modi Government were far more aggressive than the previous regimes in trampling the genuine concerns of marginalized groups and regions. Recently, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee wrote a letter to Prime Minister Modi, expressing her disappointment that the government of West Bengal was not included by the Union Government while discussing the water dispute with Bangladesh. Even if it is conceded that the Union Government was able to protect the interests of India, it is still undemocratic to exclude the regional government from the talks.

From the present era to the conflicts in the past, it is evident that the failure to share power with minorities and make decisions based on dialogue and consensus created a human tragedy of untold magnitude. From the Punjab crisis to the problems in the northeast, Jammu and Kashmir, and the southern states, the heart of the problem lies in the failure of the top leaders to share power with other stakeholders. That is why the mourning over coalition politics is uncalled for and undemocratic as well.

Before I conclude, let me appeal to the critics of coalition politics to look at the functioning of the new tenure of the Modi Government. They should not miss the positive changes. The failure of the BJP to get a majority, coupled with the significant gains made by the opposition parties, has somewhat democratized the functioning of the government. After a gap of ten years, we have in Parliament the Leader of the Opposition, questioning the failure of the government. While the law says that the numerically largest party in the Opposition should be invited to give the Leader of the Opposition to the House, an excuse that the opposition party should have at least 10 percent of the total strength of the House was used to deny the Lok Sabha of having the Leader of the Opposition.

It should not be a matter of concern but a source of joy that in Parliament, the voices of the opposition leaders are now loud. Similarly, the allied partners of the BJP, who were nowhere in the photo frame, are now seen sitting close to Modi. These changes are all due to the return of coalition politics. However, it is not being argued that all is well. But it also cannot be overlooked that the scenes from post-June 4, 2024, onwards are far more beautiful than those from 2014 to 2024.

(Dr Abhay Kumar is an independent journalist. He is interested in social justice and minority rights. Email: debatingissues@gmail.com)