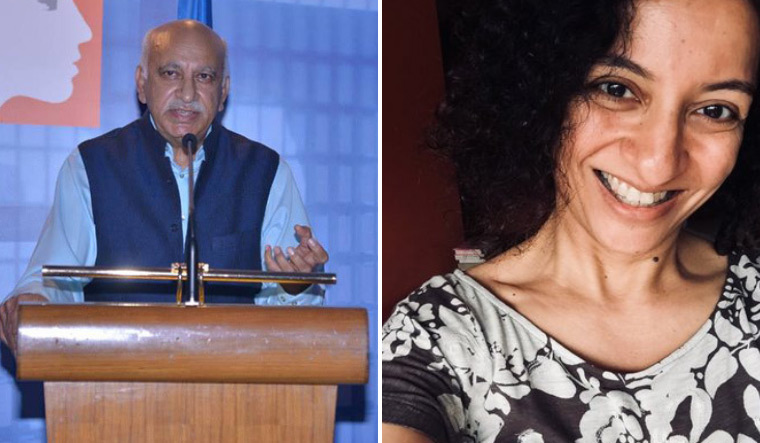

A much needed refresher course in law, ethics, journalism, and the importance of speaking out against injustice came to the fore again, as hearings resumed in the Priya Ramani Vs MJ Akbar case. Ironically this case is that of politician and journalist MJ Akbar, once a minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, alleging defamation of his ‘stellar reputation’. He is counter-suing, to use a non legal term, the eminent journalist Priya Ramani, who has accused him of sexually harassing her when she was a junior and he was her boss.

Ramani has stood by her allegations over the past years, and has in turn empowered other women journalists to come out with similar stories of being sexually harassed by Akbar over the years. The #MeToo movement in India, especially Indian journalism, cost Akbar his ministerial job, as his political patrons chose to distance themselves.

As expected, Ramani, a survivor of the sexual attack, was asked in court about the ‘delay’ in reporting the crime when it happens. There was a “vacuum in law 25 years ago,” was her brief and powerful reply. “When the incident took place in 1993 there was a gap in the law…whom could have I complained to? Legally I could not have evoked sexual harassment act because it was not in place,” Ramani said. The powerful statement, put forth by Ramani’s lawyer Rebbecca John, one of the leading criminal law experts in the country, was reported by multiple media outlets. It is a testimony of resilience, and of the fact that it is never too late to seek justice, and the time is always right, so that no one else has to suffer scarring attacks like sexual harassment at the workplace by those in authority.

Former Union minister M J Akbar’s case in the defamation suit against her was centred on his “stellar reputation”, but this was false and “I had every right to contest it,” journalist Priya Ramani told a Delhi court on Tuesday. The submissions were made by her lawyer Rebecca John, who made her final arguments before Additional Chief Metropolitan Magistrate Vishal Pahuja. However, the arguments could not be concluded, and the matter was deferred to September 14, stated a report in the Indian Express.

In 2018 as the #MeToo movement was picking up in India, Ramani had accused Akbar of sexual harassment, the incident took place around 25 years ago when she was a junior journalist, and he a powerful editor. After she had made the allegations, Akbar was eventually forced to resign as a Union minister in October 2018, and more women who had once worked as his juniors also came forth with similar allegations. He then slapped a defamation case on Ramani.

Once hearings resumed in that case, senior advocate Rebecca John told the courts that Ramani’s tweets were based on her own experience with Akbar. “Her experience is the fulcrum on which good faith rests. It is validated subsequently by the combined experience of multiple women making similar allegations,” John is reported to have said in Scroll, Indian Express and other media. John added that many spoke (on the issue) before her tweet while many spoke later. She said Ramani made the allegations in October 2018, since there was an “avalanche” taking place in India during the global #MeToo movement and that she felt “compelled to speak” after she saw several women, who had worked under Akbar between 1993-2011, speaking out against him.

It is reported that Ramani made the allegation in her “good faith” because “it was based on her own experience and that of multiple women who spoke publicly,” stated John, adding “Ramani said it was important for women to speak about sexual harassment at the workplace. She hoped that the disclosure would empower women and encourage them to speak up. Silence is not an option. Speaking out on sexual harassment at workplace is in public good.”

She added that “it was important and necessary for women to speak up. Women are taught that silence is a virtue. This case has come at a great personal cost. I have nothing to gain. By keeping silent. I could have avoided (a lot of trouble). But that would not have been right.”

John cited Ramani, saying that women fought a long battle. “The delay was on account of the fact that there was a vacuum in law and there was no platform either. Women at that time were told to keep silent. It was a different world in 1993. I cannot say with confidence that it was a fair world. It took us all a lot of time to fight and establish our battles,” John said. John said that seeing other women speak, “I (Ramani) felt compelled to speak.” Citing the allegations made by various women, Ramani’s counsel refuted Akbar’s claim that he had a stellar reputation which was lowered by her, John said “none of his claims in respect of his stellar reputation can be sustained.”

Akbar had even questioned why Ramani deleted her Twitter account, she replied to the court that, “I (Ramani) need nobody’s permission to delete my Twitter account. It was not an evidence in the case. It is my democratic and constitutional right to do so. I was not ordered by court to not do so… moreover my Tweets the complainant is relying upon in the case have not been denied by me.” According to John the testimony made by Ramani’s friend Nilofer, whom she had reportedly stated about the alleged incident soon after it had taken place, “corroborates Ramani’s truth”. “Nilofer’s message to Ramani in October 2018, after she tweeted about alleged incident also corroborate the truth stated by the scribe,” the news reports quoted her, she added that Nilofer was “a witness of impeccable quality.” She further said that Ramani’s allegation was not politically motivated and her tweets were based on her own experience with Akbar.

Akbar had stated in court that Ramani had defamed him by calling him with adjectives such as ‘media’s biggest predator’ and thus harmed his reputation. He also denied all the allegations of sexual harassment against the women who came forward during #MeToo campaign against him.

He alleged defamation, telling the court that the allegations made by Ramani in an article in the ‘Vogue’ and the subsequent tweets were defamatory on the face of it. He stated that “the complainant had deposed them to be false and imaginary.” However, Ramani has maintained that her move would empower women to speak up and make them understand their rights at the workplace.

The Scroll quoted Ramani: “This issue touches a public question and public good. Next landmark in the sphere was in 2018 when #MeToo movement began in India…They say I made these allegations because he’s a member of a particular political party. The delay was on account of the fact that there was a vacuum in law and there was no platform either. A gap in the law was recognised by Supreme Court in 1997. My incident is of 1993. Whom could have I complained to?”

Priya Ramani had first made allegations about an incident of sexual harassment by an acclaimed newspaper editor, in an article in Vogue India in 2017. She identified Akbar as that editor in October 2018 during the #MeToo movement, in a series of tweets. Soon after this, around 20 more women accused Akbar of sexual misconduct over several years during his journalistic career before he became a politician, reported The Scroll.

An article in SabrangIndia from 2019 recalled how Ramani was “cheered on by family, friends, and colleagues”, while Akbar was alone and friendless. “This image of women standing with each other against a powerful predator who came to the courtroom that day, and also on the first day of the cross-examination earlier this month, speak volumes about women solidarity in the media,” it stated.

This time too, John’s arguments were airtight and based on facts, a case in point: “Ramani’s stand is credible, reliable and she has not shaken on material facts,” John said. “They [complainant] shied away from the hotel incident. You can prove that he never stayed at the hotel. But they didn’t because Ramani is speaking the truth…Facts which, though not in issue, are so connected with a fact in issue as to form part of the same transaction, are relevant, whether they occurred at the same time and place or at different times and places.”

Akbar had denied meeting Ramani in a hotel room where she alleged he had sexually harassed her. In February 2019, Ramani was granted bail on a personal bond of Rs 10,000 in the case. Akbar has denied all the allegations against him.

Related:

#MeToo: From Courtroom to Cinema

Why the ‘Me Too’ movement in India is succeeding at last

On Akbar and the #MeToo Movement

After #MeToo: Legal System Needs Change

AIDWA Demands Resignation of Minister of State for External Affairs, M J Akbar

Delhi HC sets aside stay in Mahua Moitra’s defamation case against Zee’s Head

Siddaramaiah and Kumaraswamy booked for sedition and defamation

Scribe booked for alleged defamatory content against PM Modi and CM