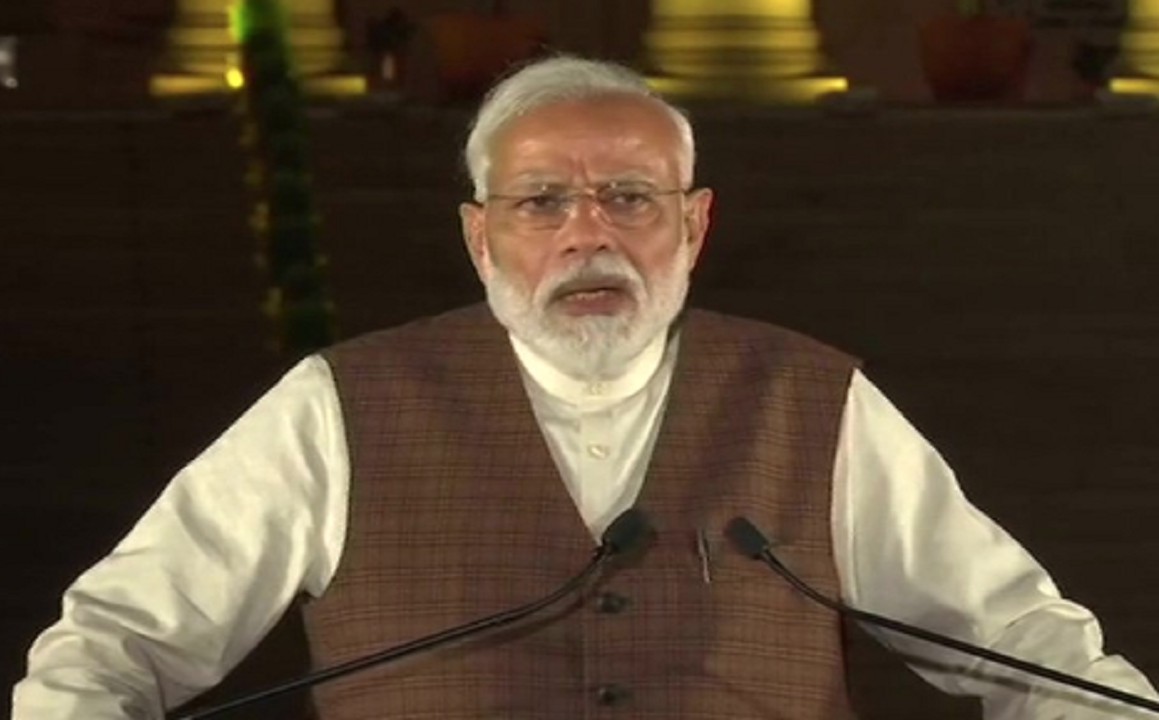

On May 25, addressing a meeting in New Delhi of the newly-elected BJP-NDA MPs after the landslide victory at the hustings, Narendra Modi proclaimed “it was the responsibility of all elected Members of Parliament (MPs) to not just work for those who had faith in us but also try to win the trust of others”. To the “sabka saath, sabka vikas” promise of his first term as Prime Minister (never mind the actual delivery on the ground) he has now added “sabka vishwas”. “Nodoby should be ‘other’ for us”, he aserted.

Within hours of his assurance of a new dawn, however, a handful of his bhakts from Gurugram, a city within shouting distance of the national capital, and another one from Bihar dared him to walk the talk. Will Modi now match words with deed?

Mohammad Barkat Alam, 25, a tailor, was returning to his shop around 10 p.m. after namaz at the local Jama Masjid on Saturday when half-a-dozen men accosted him in a public place. They flung his skull cap to the ground, demanded that he chant ‘Jai Shri Ram’ and ‘Bharat Mata ki jai’. On refusing to do so he was thrashed with a stick. According to news reports when he sought help others present on the scene just laughed at him.

After keeping him at the police station for six hours on Saturday and Sunday, the police registered a case on charges of promoting religious hatred, causing hurt, criminal intimidation and unlawful assembly. We will now be told that the law will take its own course and the guilty will be punished. Believe it if you will for that is not what happened in the five years of ‘sabka saath, sabka vikaas’.

The very next day, a man named Rajiv Yadav shot at a Muslim youth, Mohammed Qasim, and told him, “Go to Pakistan”. In a video shared widely on social media, Qasim later narrated that none of the people witnessing the incident came to his aid.

To his credit, the newly-elected BJP MP from Delhi, Gautam Gambhir put out a tweet describing the Gurugram incident as “deplorable” and called for “exemplary action” against the culprits. For this, the cricketer-turned-politician was targeted by trolls while a section of BJP leaders expressed concern that his condemnation would be used against the BJP.

What can, or will, Modi do? He can choose to say or do nothing, as earlier, when Muslims were lynched by ‘cow vigilantes’ and other ‘desh bhakts’. Recall Mohsin Khan (Maharashtra), Mohammad Akhlaq (U.P.), Pehlu Khan (Rajasthan), Hafiz Junaid (Haryana), Murtuza Ansari and Sirabuddin Ansari (Jharkhand), Hafizul Shaikh (West Bengal), Mohammed Riyaz (Karnataka), Afrazul Khan (Rajasthan). Or, he can do something altogether new: take one symbolic step to kindle hope in the hearts of India’s hapless Muslims.

Alam was targeted simply because he was a Muslim, the skull cap on his head his only sin. How about Modi and his party president, Amit Shah leading a road-show in Gurugram, skull-cap on their heads in a symbolic gesture? How about him holding hands with Alam at the rally to declare: Alam is us, those who attacked him for no reason are against us? Isn’t that what Modi meant when he declared on May 25 that “nobody should be ‘other’ for us”?

Is this too much to ask of a leader widely believed to be bold and decisive, a leader from whom one can expect the unexpected? We will soon know. But we do have examples before us of how leaders elsewhere respond to hate crimes in their midst.

In January 2001, a day after a black youth was stabbed to death by two white supremacists in Norway, the then Prime Minister, Jens Stoltenberg, accompanied by Oslo´s bishop, Gunnar Stålsett, and the city´s mayor, Per Ditlev Simonsen, led a protest march in Oslo, the national capital. “This is not our way, we shall not tolerate hate crimes,” vowed the prime minister at the rally. The lead taken by him triggered countrywide rallies and cultural performances denouncing hate crimes.

Or, we need only recall the spontaneous words of the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern, in the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks on mosques in Christchurch in March this year. “Many of those who have been directly affected by their violence may be migrants,” she said. “They may even be refugees here… They have chosen to make New Zealand their home. And it is their home. They are us. The persons who have perpetuated this violence against us (emphasis added) is not. They have no place in New Zealand”.

By her several symbolic gestures – a headscarf covering her head while consoling her country’s Muslims, opening her speech in Parliament by reciting verses from the Qur’an – Ms Ardern gave a new meaning of “us” and “them”. In the process she found her way into the hearts of millions of Muslims across the globe.

That more than anything explains the response of many Muslims in Mumbai when Islamic extremists perpetrated their terror act against Christians, and others, in Sri Lanka on Easter Day, just a month after Christchurch. The victims of the bombings in Sri Lanka are us, Muslims who targeted them are not us.

Modi’s nobody-should-be-‘other’-for-us statement may remind some of Ardern. But for India’s Muslims, who have been hounded and wounded by the words and deeds of his party and parivar wedded to Hindutva, whose very foundation is built on the “us” vs “them” divide, it will take more than sound-bytes to restore some hope, let alone trust.