Your tale of navigating the NRC process in Assam

Let me introduce you.

Jamila Begum, forty-four years old,

from Barpeta, Assam.

I know this is not the best time — the monsoon is here; the river is furious and your village is flooded — but we also do not have much time left. The final NRC list comes out very soon. We met at your tin-walled house, built so for flood resilience. Your four children were there — a boy and three girls. Two of your daughters are married, the third engaged. The son is still in school, which is now shut because of the floods.

The day we met, you told me that you have not been able to work in your small field ever since you have had to go around figuring out why your name did not appear in the NRC list. The village chief, gaubura, says it is because your panchayat certificate was not accepted as proof you are your father’s daughter, that Jamila Begum is the daughter Abdullah Islam, whose name was present in the 1951 NRC list. The notice says “legacy person not parent or grandparent”. Never having been to school and married off before you could have documents like a Voter’s ID or a senior school certificate that “link” you to your parents, the panchayat document was your last resort. Despite rules that attest to a panchayat document’s validity, your name still stands excluded. Your son too was not included in the list. His name was spelt differently and carelessly by the officer who made your family tree. You tell me you could not have known of the error beforehand for you cannot read, as can not the rest of your family. Notwithstanding, your fears have been compounded now that your exclusion has jeopardised the citizenship of all your children anyway.

I ask about your husband. You tell me that with income opportunities in your village dying out, he has migrated to Guwahati to be a construction worker. The police have picked him and his other Bengali-Muslim migrant friends up for “questioning” a couple times. One of them was deemed a “doubtful-voter” one day. No one in your village knows why.

You have been hearing from your married daughters that with their citizenship under threat now, their relationship with their in-laws have become sour. You had barely managed to gather the dowries during their weddings. Your third daughter’s engagement is on the verge of breaking. Without education or a fortune to fall back on, she needs a marriage to ensure her social protection — but, “who wants a foreigner daughter-in-law?”, you ask me. Foreigner, now that the government has insinuated so.

With the gaubura’s help, you filed a claim form against your exclusion. There is so much information that you wish you knew. How can you ensure that your documents are impeccable? How can you identify errors when you cannot read? There have been rumours in the village that being asked to submit biometrics at the hearing centre implies that you will be sent to a detention camp. Is it true? What will the officer ask you? Who should testify for you?

You show me the notice stating your hearing date and centre. There are so many abbreviations in it — even the gaubura does not have answers. The centre is far away from your house and nine of your relatives are listed to testify. You tell me that the hearing day was a difficult one. Your siblings and you had to stay away from your fields and jobs for a long time, as did your children from their schools. Local buses did not go the centre so you had to hire a mini bus for your family. Luckily, a neighbour loaned you the money for it. The hearing was on a hot sunny day, but the centre had no shade for people to rest under. Your niece had to look around for hours to find a place to feed her baby and rest. The news of infants dying at hearing centres had terrified her.

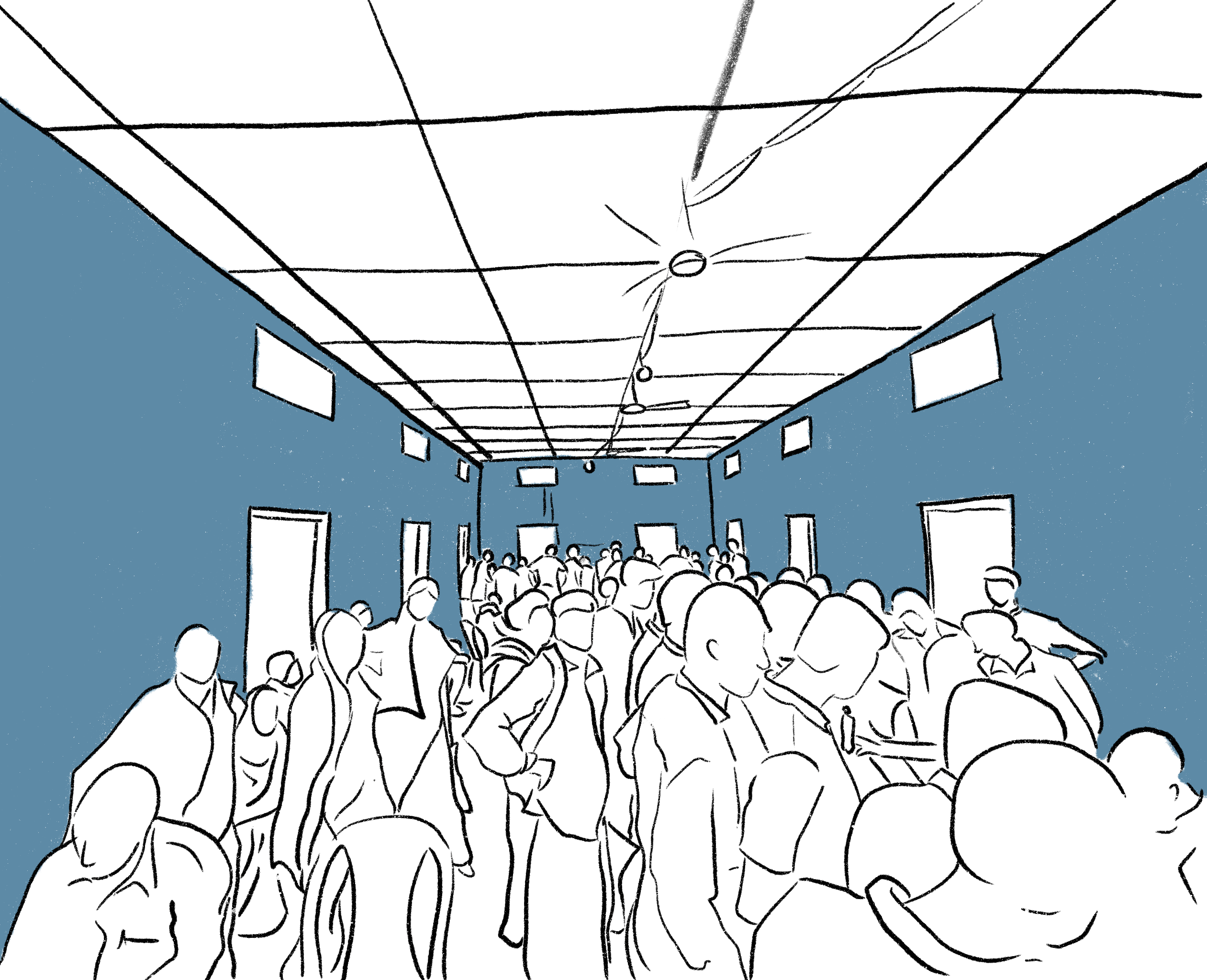

The hearing was in a large room lined with desks. An officer sitting behind each of them. All of them men. There were people everywhere, going from one desk to another in no particular order. Some looking as lost as you did, some scrambling to find papers from their well-worn plastic bag of documents. For a woman who had spent most of her life interacting only with her family and neighbours and with very few men from outside, having to answer all these strange intimidating men was daunting. When your turn to be heard finally came, you realised that the officer spoke only Assamese and did not understand the Bengali dialect your family spoke. When I ask you how the hearing went, you tell me that you do not know. They wrote down the testimonies from your family, but you were not literate to read it before you signed on them. You showed the officer the documents that you thought he was asking — he seemed to be using different words for them.

“Are you confident about the results?”, I ask. “No”, you say. The officer joked with an insinuation that you were Bangladeshi. He was laughing, so you could not really tell what he meant. You are still worried about whether you had all the right documents. Nevertheless, the official hearing results have not come out yet.

Now we wait.

“Are you afraid?”, I ask. “Yes”, you say. “Why?”

“They will take us to detention centres.”

Most social workers working with the Bengali-Muslims on the char-chapori region of Assam observe that a majority of those left out of the NRC are women (lack of transparency at the state’s end prevents us from finding out the actual numbers). This state-created statelessness has brought about a combination of vulnerabilities to these women. While exclusion from the list disenfranchises them and erodes the already thin layer of social protection they enjoy, the process of fighting their exclusion itself is particularly challenging. The system’s failure to take into account their realities — such as poor education and literacy, early migration due to marriage, and life in a fragile ecology that affect the thoroughness of their documentation — has resulted in women being the primary targets of this project. The process further goes to ignore the experiences of women (and other gender minorities and the disabled) during the claim process which makes it particularly arduous for them and is therefore systemically discriminatory over and beyond the exclusionary agenda of the NRC process.

Varna Balakrishnan is a research fellow at Karwan-e-Mohabbat, New Delhi. Her work focuses on issues based on citizenship, gender, and communal hate crimes.

This narrative is based on the information gathered by Varna Balakrishnan during her field work as part of the Karwan-e-Mohabbat from 1st to 6th July 2019, in Kamrup and Barpeta, Assam. All incidents in this narrative are based on true events and testimonials.

All Illustrations by Krishna Balakrishnan.

Courtesy: Indian Cultural Forum