Even as Lucknow’s Ekana stadium shines in its moment of glory, having hosted an unprecedented number of international cricket matches, a small marshy patch of tall grasses and dead trees right behind it has been playing host to a World Cup of its own. Hundreds of foreigners have arrived for this annual event and, oblivious to the per square foot realty rates, have occupied every available square foot of premium land and sky around the stadium. These guests are interested in cricket but only of the insect variety. They say in the West that one swallow does not a summer make; twenty thousand Barn Swallows in the Ekana sky have announced the arrival of winter in Lucknow.

The Barn Swallow is a sparrow-sized, agile bird that spends a majority of its life in flight – eating, drinking, and even bathing on the wing. In summers, they breed in the Northern latitudes, above the Himalayas, and when the Earth tilts away from the sun, they flock to Africa and India in millions, accompanied by a new generation. Drive straight on the road leading away from the Palassio mall until you reach water bodies surrounded on all sides by large construction sites, and it’s likely that you will come across thousands of Barn Swallows congregating on electric wires or swooping down one by one on the water below, snagging small insects mid-air. In flight, their bellies appear in many variations of creamy-white with a rusty-coloured neck (hence the scientific name Hirundo Rustica), with wide outstretched wings and a deeply forked tail. Their flight is convoluted, zig-zag, evolved to mimic the unpredictable moves of their prey. When perched, in a ‘bent-forward’ position, their cobalt-blue primary feathers can be seen. These thousands of Barn Swallows feed on insects that rise from a collection of water bodies that dot the area around the stadium.

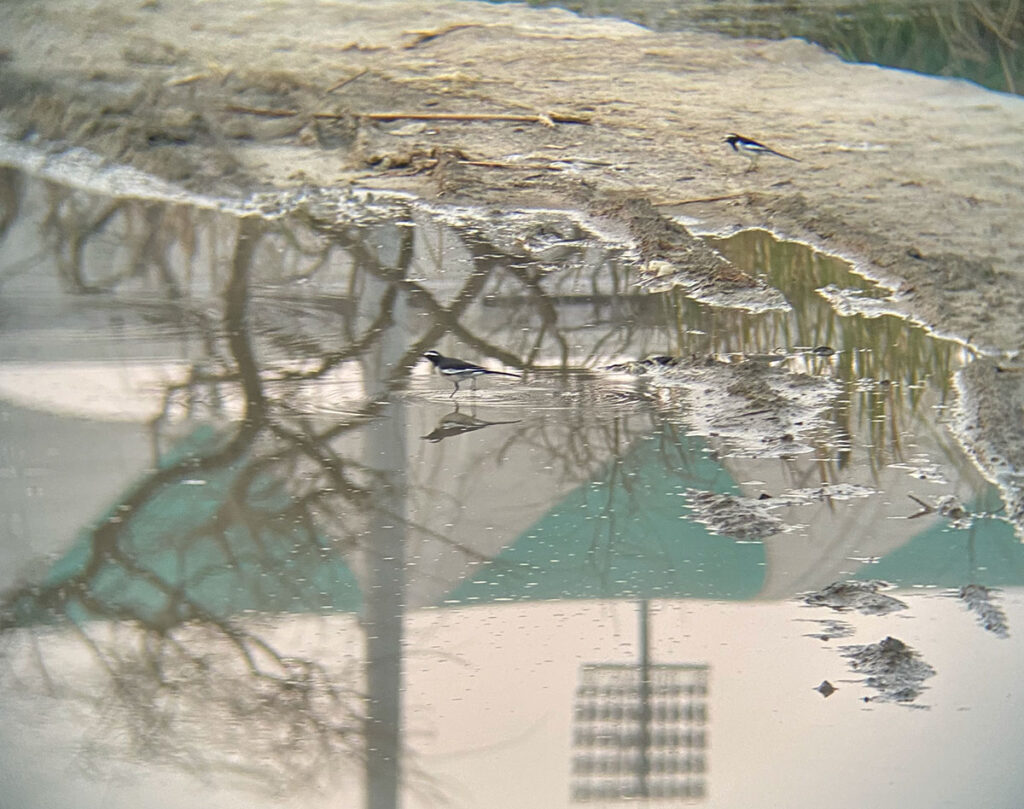

Nearby lies the Ekana Wetland, now protected by a government order, with work on a watch tower and walkway already in progress. On the afternoon I visited the wetland, young men in large cars were using the ‘natural’ backdrop to record reels, performing reverse somersaults to loud cheers. Behind them, at least two species of wagtails were performing tricks of their own. No less raucous than similar specimens of the human species, these highly vocal, long-tailed immigrants arrive in Lucknow in large groups at the onset of winter and promptly take over feeding areas. The wetland, in this case, is overtaken by their (mis)behaviour. Both species—the white-faced, sombre white wagtail and the black-faced, white-browed wagtail—can be seen chasing each other from one low bush to another. If birds made reels, these immigrants would be best known for the animated twerking of their backsides, which incidentally gives them their name—wagtails.

I walk away from the crowd, towards the stadium. Various water birds call from the thicket. This is home to the Purple Swamphen, a large bluish-purple bird with an amusing tuft of white hair under its tail. Apart from the usual waterhens and moorhens, the wetland also hosts the stunning jacanas – I have seen both the Bronze-Winged and the Pheasant-Tailed Jacanas here – ‘walking’ on water on their elongated toes and nails. In Jamaica, these jacanas are also called ‘Jesus’ birds for this miraculous feat. However, in flight, the bird loses its glamour, appearing gangly with long thin legs awkwardly trailing behind. These water birds, pretty as they are, unfortunately emit a range of off-key, raucous cackles starting from the guttural to the high-pitched, which at times can sound very human-like. Presently a man emerges from the bend with a beer can in hand, looking positively harried. He looks around, alarmed. “Ye kiski awaz hai?” Who is making these sounds? he asks. I tell him about the waterbirds and lend him my binoculars to persuade him. This convinces him. “Humne socha chudail hai. I thought it was a witch.” He says, relieved. He then requests me to take a picture of him with the binoculars. I am asked to hold his drink as he turns into an ornithologist and peers into the marshes pensively.

The witchy cackle is the quintessential wetland sound, its resident symphony. From the croaking Egrets to the laughing White-Breasted water hens, water-birds deploy a uniquely multitude of non-musical calls and songs. Here, in the gathering dusk, Ekana resembles a ghost town. From the tall grass that lines both sides of the path, rise the skeletal remains of babool trees. Devoid of leaves, these wooden towers provide the birds with an ideal perch to survey the marshes around them. In turn, they offer an unmatched view to the birdwatcher who can observe these birds unhindered. This is one of Ekana’s unique specialties.

Hunched, on two adjacent branches of a babool, sit two Indian rollers. The otherwise drab, brown-ish bird reveals a dazzling blue under its wings when in flight. A hundred years ago, Rudyard Kipling’s father wrote about the roller in his book, Beasts and Man in India, saying, ‘ “Undreamed-of wings he lifted,” a quotation that comes to mind when this gray and sober-looking bird suddenly rises and displays the turquoise and sapphire-tinted splendor of its wings’.

It can be seen year after year occupying the same perch—the bare limb of a towering tree or an electric wire. Salim Ali called it the farmer’s best friend for its steady diet of insects and other pests of standing crops. The acrobatic bird is known for gliding and dropping down on prey, battering it mercilessly against the perch before swallowing it; a certainly delisghtful sight to the farmer.

In Northern and Central India the roller is also known as Neelkanth for the faint blue under its neck, the colour of poison that Shiva drank. A sighting of the Neelkanth on Dusshera is considered to bring good luck, for it is said to deliver messages to Ram himself. On the internet, I came across this simple Haiku:

Neelkanth tum neele rahiyo, dudh bhaat ka bhoj kariyo, hamri baat Ram se kahiyo

(Neelkanth, you stay blue, feast on rice and milk, and convey our wishes to Lord Ram).

The Indian Roller is also the state bird of Karnataka, Telangana, and Odisha. In press handouts, published on social media, keen birdwatchers can spy a framed portrait of the Indian roller in flight on the walls of Congress president Mallikarjun Kharge’s New Delhi residence.

The State of Indian Birds report released this year, reports a fifty percent drop in the Indian Roller’s numbers. This was perhaps one of the most surprising revelations in a report that already paints a difficult picture of India’s avifauna. This drop in numbers of the commonly seen roller is almost certainly due to the loss of habitat and the indiscriminate use of pesticides. But that evening in Ekana, I counted at least six rollers including a juvenile.

As the sun sets around me, a mustering of Open-Billed Storks (Ghonghil in Hindi) arrives at the wetland. A low Babool tree close to the stadium is the communal residence of this gentle bird. The name comes from a permanent gap between its reddish-brown beak which helps it extract the soft parts of its favourite food—freshwater snails or Ghonga. One after the other, in the falling light, the storks glide regally back home. In the distance sits a majestic Nilgai, perhaps reflecting on one or another lofty questions of existence. I am close to the stadium and mall now, and can hear the thump of distant music. Behind me, water is being pumped out to make way for the foundation laying of a large mall. A car, perhaps returning from the site, sounds its horn and flushes a bird out of hiding. It is a heron judging by its long neck and long, pointed bill, though I have never seen it before. The bird is a glossy black, with yellowish stripes on the neck and white spots on its back, which on the deep black of its wings, look like stars in the night sky. It looks vulnerable and out of place. When a Pond-Heron takes an unkind swipe at it, flying low over its head, it ducks awkwardly. This is most certainly a rare sighting of the elusive and solitary Black Bittern. Crepuscular and nocturnal, it is most active at dusk and dawn. A bird of thick cover, seen sparsely outside, freezes when startled. The Britten sat on the branch long enough to give me the opportunity to admire it at length. This must be the Dussehra good luck granted to me by the Neelkanths.

As other birds fall silent one by one, a steady hum rises all around me. The darkening sky above the Ekana wetland is filled with tens of thousands of chattering Barn Swallows, flying in no particular pattern, in no particular rhythm, but simply in the celebration of being alive, marking the end of another day. It is a joyous, magnificent melody. A once-in-a-lifetime sight.

Even though the Ekana Wetland itself is under government protection; the extraordinary diversity of birds that arrive here every winter, as well as the resident ones, feed on the various water bodies scattered throughout this area. Most of these water bodies, marshes, and wetlands, though lying in the Gomti’s flood plain, are in-turn fed by water being pumped out of the ground for foundation-laying of active construction sites. Many of these water-bodies themselves seem to be earmarked as construction sites. Soon, the digging will stop, and construction will begin. Families will move in, shops and malls shall be made available to them. In a few years, the ‘Bird Sanctuary’ or Eco-tourism centre of Ekana will become an island in the middle of a sea of high-rises. Eventually it will only support a fraction of the birds who now live or migrate here. This is after all how habitats are lost. This is how species are lost.

Alone in this wilderness, with the star-studded Bittern, water-witches, a sky full of swallows, and a forest of dead babools, I wonder what is lost when a bird disappears.

In Aesop’s fable, a young boy, fond of gambling, sells off his only cloak when he sees a swallow fly by, convinced that spring is around the corner and sadly, freezes to death. In our mad scramble to build our houses over the nests and homes of others, convinced of our immortality, perhaps we are ignoring a warning in plain sight—that it is only a matter of time before a land not suitable for a bird becomes unsuitable for us.

(Suhel B is a writer and filmmaker)