What does the power struggle between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and powerful Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen mean for Turks who want democracy?

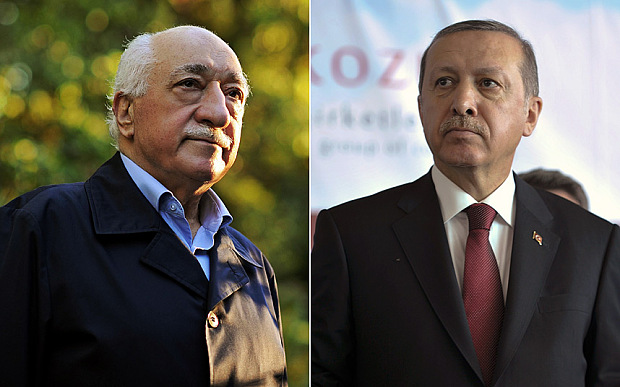

Fethullah Gulen (Left) and Recep Tayyip Erdogan Image: AP/Getty Images

Turkey is in crisis. Its President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, has declared a three-month state of emergency. His purge following the failed coup is just the tip of the iceberg, with much worse to follow. The aftershocks of Turkey’s failed coup on 15 July are unprecedented. The symbol of Turkish parliamentary democracy, the Grand National Assembly, was bombed by members of the country’s own security forces; police and military forces exchanged gunfire and coup plotters attacked civilians on the streets of Istanbul and Ankara. The human toll is high: there have been around 232 deaths, over 1,541 injuries, according to official figures, and more than 60,000 state officials jailed or dismissed, with numbers increasing ever day.Turkey’s international image as a strong member of NATO and a bastion of stability between Europe and the Middle East, has been damaged. Tensions in US-Turkey relations have increased since Ankara demanded the extradition of Pennsylvania-based Islamic cleric Fethullah Gülen, who is blamed by Erdogan for the coup attempt.

Turkey’s international image as a strong member of NATO and a bastion of stability between Europe and the Middle East, has been damaged.

On 15 and 16 July, people on the streets, as well as all party leaders —including AKP’s opponents sided with ‘democracy’. Or rather, with Erdogan. Once Erdogan was assured that the government had taken control, he quickly announced that this was “a coup attempt by a small faction in the military, the parallels (Gülenists).” Since 2010, Erdogan has accused the Gülen movement of running a ‘parallel state’ with the aim of overthrowing the AKP government. Erdogan said that this is “a gift from God to us because this will be a reason to cleanse our army”.

During his tenure in power, many argued that taking the army out of Turkish politics was one of his biggest achievements. However, Erdogan had in fact successfully co-opted high-ranking army officers. In the post-coup cleansing, Erdogan’s purge has extended beyond the army, including high-ranking officers of the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK), to the police, the judiciary, the National Intelligence Agency (MIT), the Ministry of Education and universities.

There is little doubt that Erdogan’s divisive and increasingly authoritarian policies pose a serious threat to Turkish democracy and secularism. The crux of the matter is Erdogan’s increasing personal power since his ascendance to the presidency in 2014. Prior to winning Turkey’s first presidential elections, Erdogan similarly blamed the Gülen cemaati (community) for creating a "shadowy state" within the Turkish state and engineering a "Gulen-Israel-axis" in order to overthrow him. This time the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that “this was more than a treacherous plot: it was a terrorist campaign”, the illegal “Fethullah Gülen Terrorist Organisation” staged it, and the “terrorists will be punished in accordance with the law”. The key to contextualising these allegations lies within the history of Erdogan’s relations with the Gülen movement, known as Hizmet (service) in Turkey.

Who is Fethullah Gülen?

Fethullah Gülen’s rise in Turkish politics began in the 1970s. Born to a pious family, Gülen became an imam and a spiritual leader who emphasised the importance of education to provide a moral compass for young people. His influence grew continuously within the country. He opened private schools, private tutoring centers and dormitories called ‘houses of light’. The origins of the Gülen movement were founded by the alumni of these schools, who built up a network of pious young businessmen and Muslim charity foundations. Following the 1980 military coup, the generals acting as the ‘guardians of secularism’ became highly suspicious of Gülen’s network and accused him of plotting to install an Islamic state. Gülen went into hiding for six years.

In the 1990s, the Gülen movement found a new purpose under the rule of Prime Minister Turgut Ozal. Opening Gülen movement schools in Turkic republics supported Ankara and Washington’s neo-liberal visions for the post-Cold war era. The first one was opened in Azerbaijan in 1991, they then spread to other post-Soviet Turkic republics. In 1999, a leaked video featuring clips from Gülen’s sermons was a turning point: Gülen was accused of infiltrating the Turkish military, the police and the judiciary in an attempt to undermine the secular foundations of the Republic. Gülen was again a wanted man. He has been living in exile ever since.

In post-9/11 international politics, the role of Islam gained new momentum which has benefited the Gülen movement. Gülen’s promotion of a humanist and moderate Islam was welcomed by Washington. This was also a turning point in Turkish politics, which has oscillated between secular state and Muslim society. The devout half of Turkish society found their voice in the AKP’s populist discourses in 2002. Its new leader, Erdogan, gained popularity as a result of his being victimised in the name of secularism: Erdogan was removed from his position as mayor of Istanbul and jailed in 1998 for reciting a poem, which included the lines: “the mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers”.

Although Gülen and Erdogan never met in person before Erdogan became prime minister in 2003, they were both pious Muslims who opposed both secularism and the army’s role in politics. It was the Turkish military’s threat to the AKP which turned Gülen into a key ally of Erdogan for a decade. Gülen’s followers provided crucial support for the AKP, which subsequently secured them three election victories. In return, Erdogan offered protection to the Gülen community’s opaque businesses and pious activities.

The movement operates a global network of business, education, media and charitable organisations. Hizmet runs schools in over 150 countries, including more than 100 chartered schools in the US, and has grown into what is possibly the world’s largest Muslim network with millions of followers.

The power struggle

The power struggle to control the state has turned into an open war: Gülen is now public enemy number one and his movement is officially identified as a terrorist group

Gülen is arguably Turkey’s second most powerful man. Once Hizmet grew and the cemaat members started to be employed by state institutions in Turkey, tensions between Erdogan and Glen began to increase. A key turning point was a series of investigations carried out between 2007 and 2013 known as Ergenekon trials. Ergenekon, an ultranationalist terrorist organisation, was charged with plotting a coup against the AKP government. It was later claimed that Glenists orchestrated the trials which damaged trust between Erdogan and Glen. Thereafter, the power struggle between two factions began for absolute control of the state.

When the AKP won the 2011 parliamentary elections with a majority, Erdogan was strong enough to break his alliance with the Gülen movement. The final break came in late 2013 when Erdogan decided to close down Gülen’s prep-schools in Turkey and began to pressure other heads of states to do the same for Gülen's international schools in their countries.

In response to Erdogan’s offensive, the Glenists allegedly launched a high-level corruption probe in which businessmen close to Erdogan, party officials and three ministers’ sons were arrested. In a leaked conversation with his son, the prime minister talked about having millions of dollars stashed away in shoeboxes. Erdogan later blamed Gülen for launching a “dirty conspiracy” and Hizmet’s direct involvement in the corruption investigations. While Gülen denied all of these accusations, the AKP government has intensified the purging of state officials in the judiciary, the police and party officials considered close to the Gülen cemaati

The power struggle to control the state has turned into an open war: Gülen is now public enemy number one and his movement is officially identified as a terrorist group. In November 2015, 122 Glenists were indicted, including Glen himself. He is accused of tampering with an investigation and managing an armed terrorist organisation. On 19 July 2016, Ankara asked Washington for his extradition, while Gülen gave interviews to the international media, rejecting allegations that he was the mastermind. According to Gülen, the failed coup was staged by Erdogan himself.

There is no doubt that Gülen is a controversial figure. To his followers, he is a liberal Islamic modernist who preaches “interfaith and intercultural dialogue”. As stated on its website, the Gülen movement claims to be “a worldwide civic initiative rooted in the spiritual and humanistic tradition of Islam.” It regards Islam as broadly compatible with modernity, science and democracy. To his critics, Gülen is a threat to the secular character of the Turkish state and is plotting to install an Islamic dictatorship. The rivalry between Erdogan and Gülen is more about personal power than different interpretations of political Islam. If Ankara’s demand for his extradition is successful, Gülen might face the death penalty, the reintroduction of which is highly possible in Erdogan’s ‘new Turkey’.

In the long term, a failed coup does not mean that democracy has won

In the long term, a failed coup does not mean that democracy has won. Paradoxically, this attempt has helped President Erdogan’s quest for more power and greater authoritarian control over Turkish politics. He is perceived to be the defender of ‘civilian rule’, while simultaneously clamping down on civil liberties. It is likely that his approval ratings will rise during the next referendum planned for later this year. He will leverage this popularity into votes for constitutional change to replace Turkey’s parliamentary democracy with an executive presidency. Such constitutional changes would grant him absolute power, which is his ultimate goal under the cover of his conservative Islamism. The power struggle between Erdogan and Gülen is harmful to Turkish people who opted for democracy. Whoever was behind the failed coup did Turkey’s democracy a double disservice.

Ayla Gol is a Reader and Director of Graduate School at the Department of International Politics, Aberystwyth University. She is the author of Turkey Facing East: Islam, Modernity and Foreign Policy.

This story was first published on openDemocracy.